>> Yeo Valley Trust >>

>> Getting Back on Track >>

>> Bridge Strike >>

>> B.R. Totems >>

>> Running-In Boards >>

>> One Hundred Years since the Grouping >>

>> The Railway's War Effort at Christow >>

>> Beeching Did Not Shut the Teign Valley Branch >>

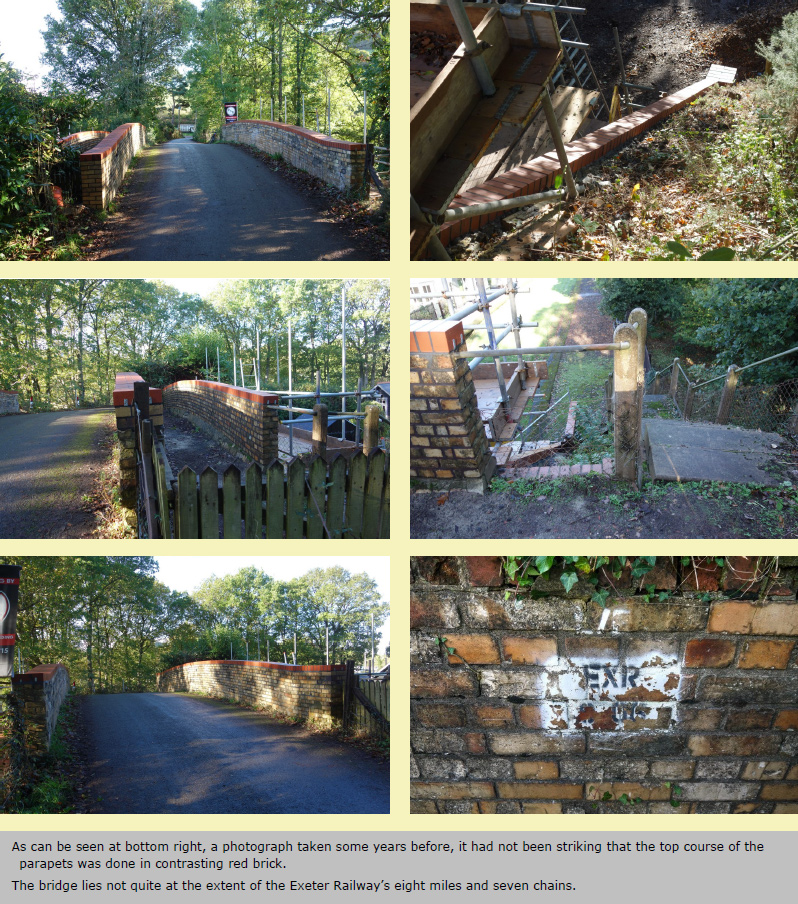

>> Christow Station Bridge >>

>> Ball Clay Mining >>

>> Main Line Diversion >>

>> There it was, gone >>

>> Behind-the-Scenes of the E&TVR >>

>> It can't or it won't be done? >>

>> Llangennech and Carmont >>

>> Position Closed >>

>> The Alamy >>

>> One Running-In Board Goes All the Way Home >>

>> Teign Valley History Centre >>

>> Conicity >>

>> Track recovery at Christow, 1959 >>

>> Heath Rail Link >>

>> Last Run of the Albion >>

>> Mountain Mine >>

>> The Permanent Way (and the Truth and the Life?) >>

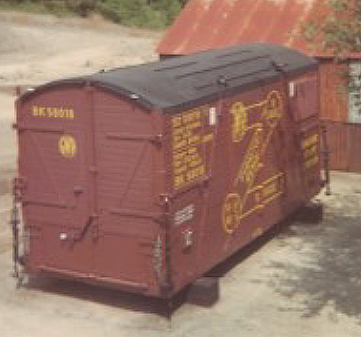

>> Road-Rail Containers >>

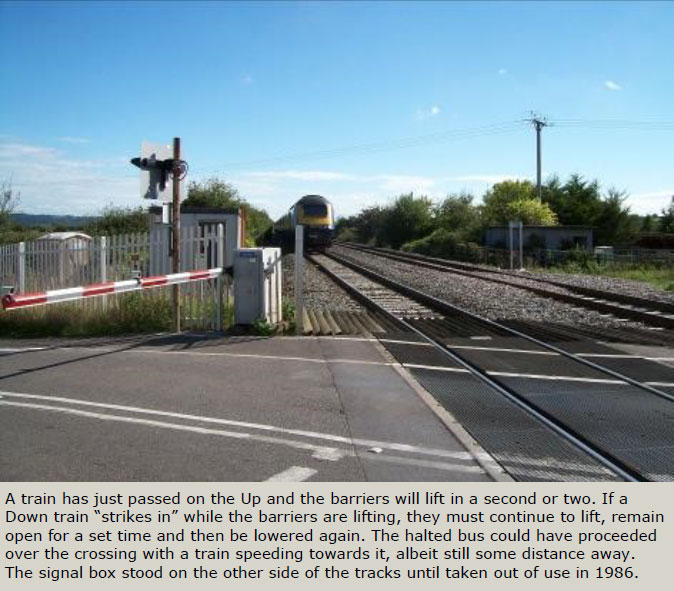

>> Hixon—50 years on >>

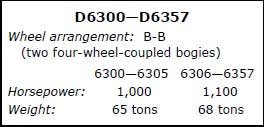

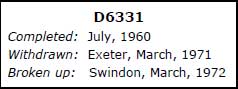

>> D6331 >>

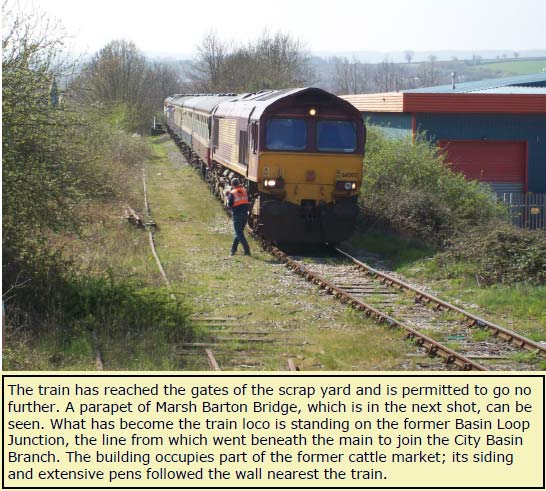

>> Exeter Railway Junction—Freight train departure >>

>> Newquay Branch—Descending Luxulyan Bank >>

>> David Shepherd, C.B.E., F.R.S.A., 1931 - 2017 >>

>> The Genus Grockle Automobilus >>

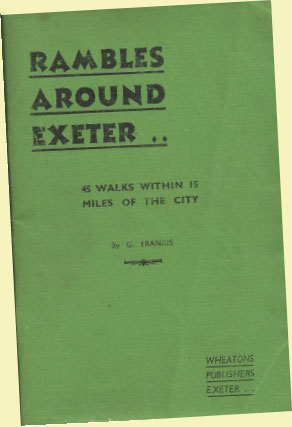

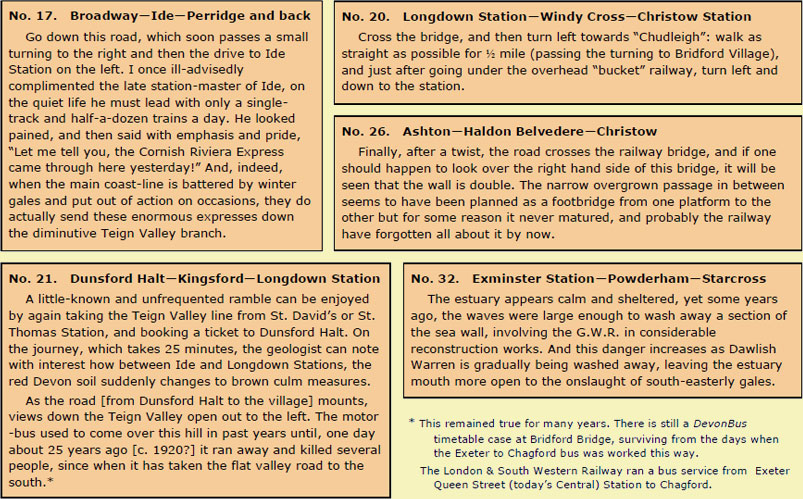

>> RAMBLES AROUND EXETER >>

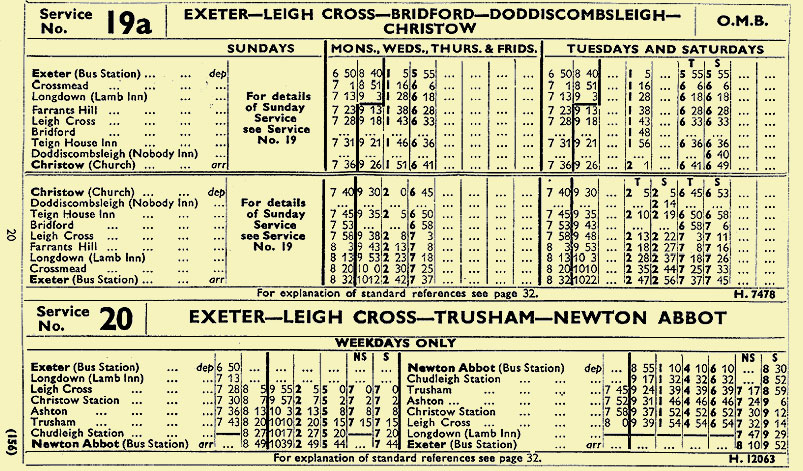

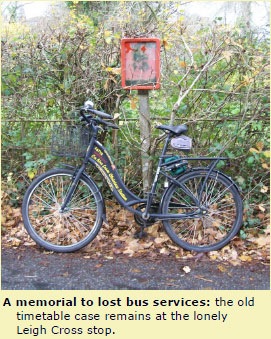

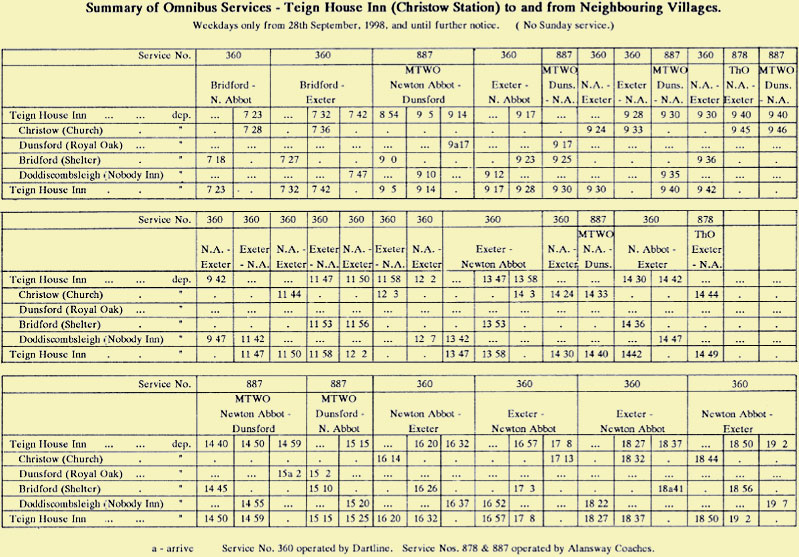

>> Once Busy Bus Stops >>

>> Searching for Albion >>

>> Railway Nomenclature >>

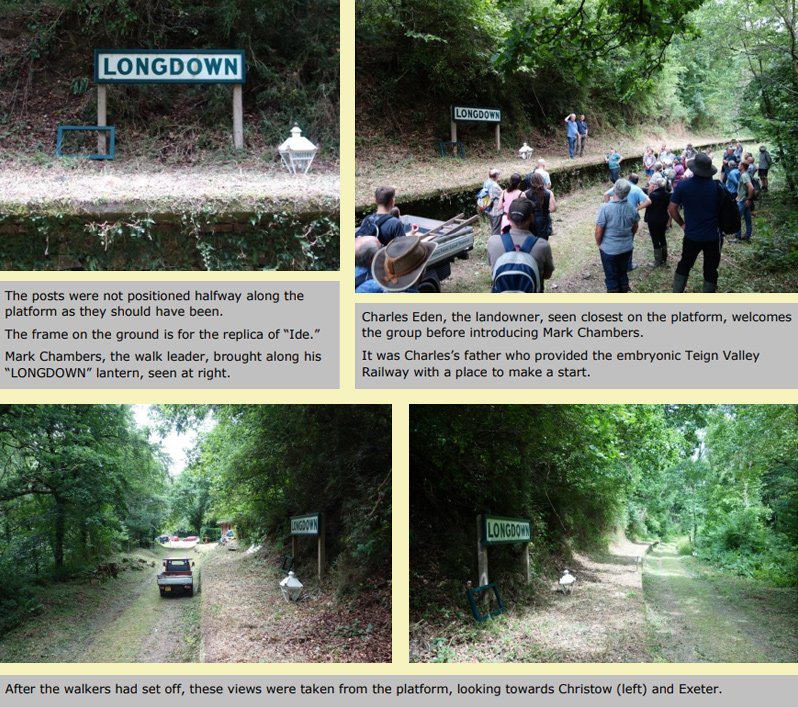

>> Visit by the Dartmoor Railway Supporters' Association >>

>> The Railway - British Track Since 1804 >>

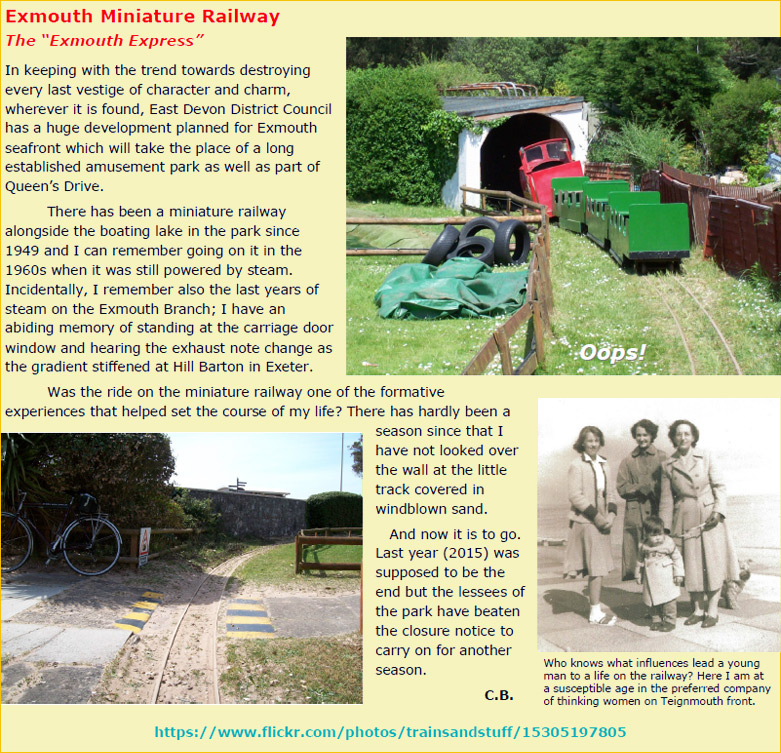

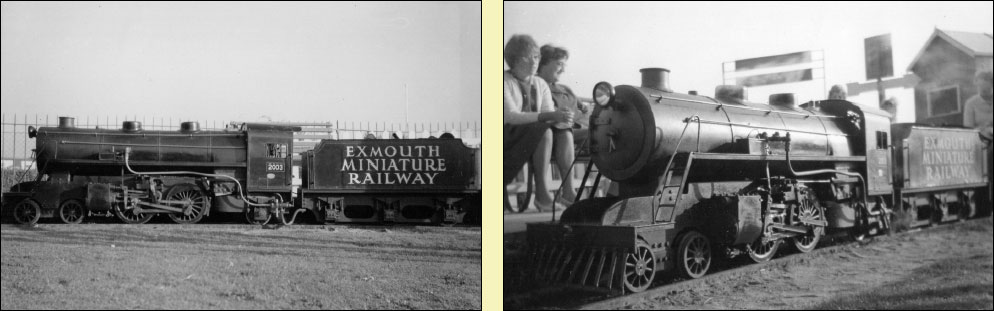

>> Exmouth Miniature Railway >>

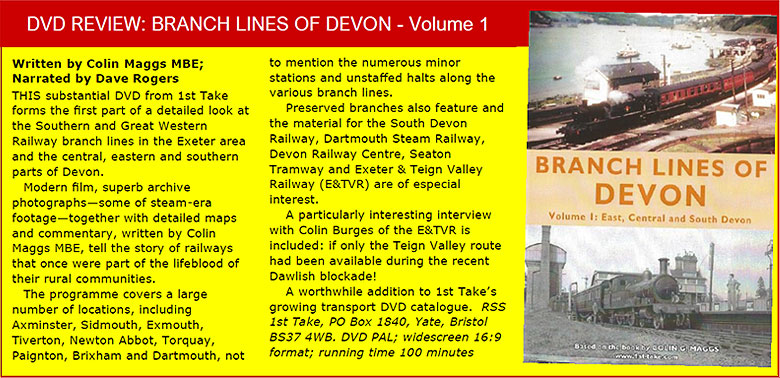

>> DVD Review: Branch Lines of Devon—Volume 1 >>

>> A Very British Map: The Ordnance Survey Story >>

>> Charity HST Special, 10th October, 2015 >>

>> David St. John Thomas, 1929-2014 >>

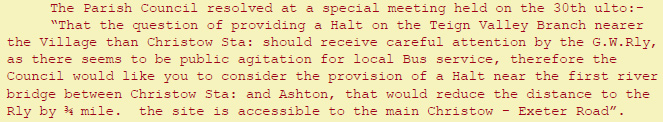

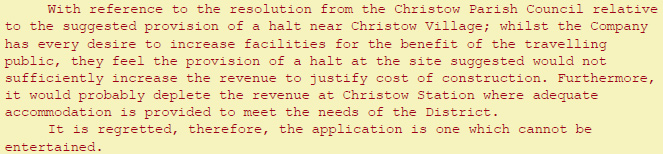

>> Visit by the Dartmoor Society >>

>> A Strange Place to Find a Shipwreck >>

>> Bovey Lane Crossing Saved >>

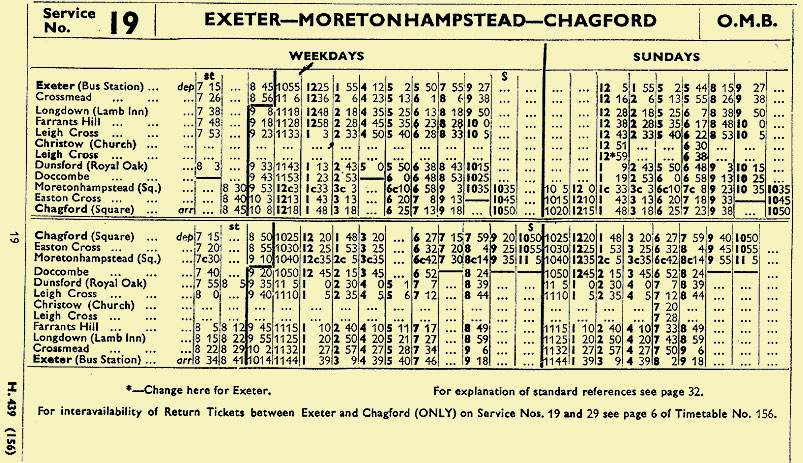

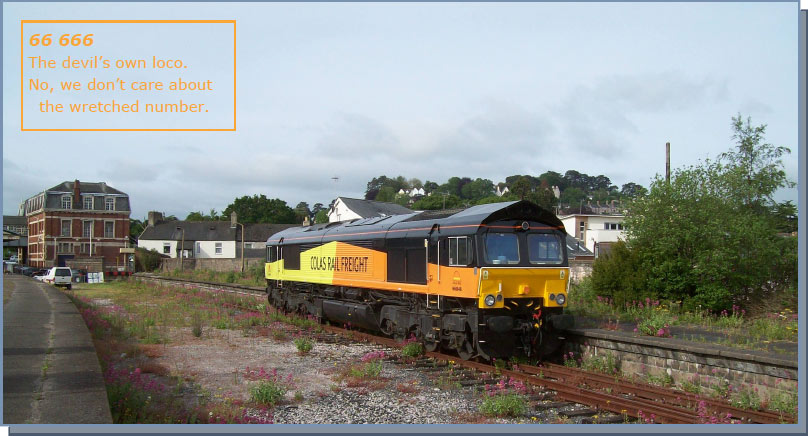

>> Special Trains on the Moretonhampstead Branch >>

>> Dartmoor Society Public Debate, 2014 >>

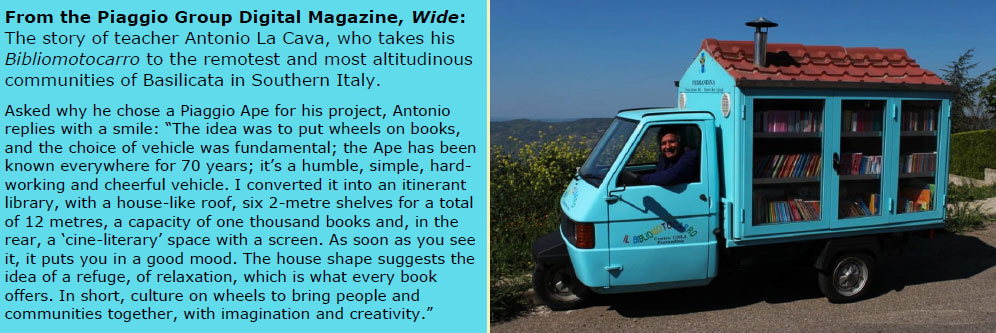

>> The Buzz Tour >>

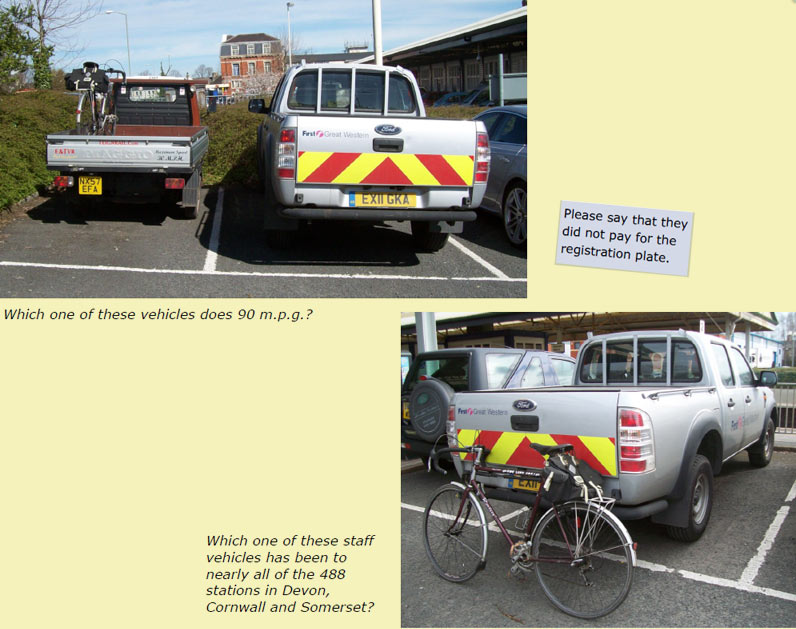

>> Caption Competition >>

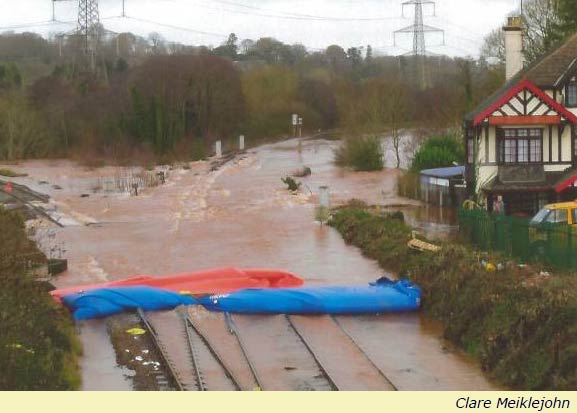

>> The Dawlish Débâcle >>

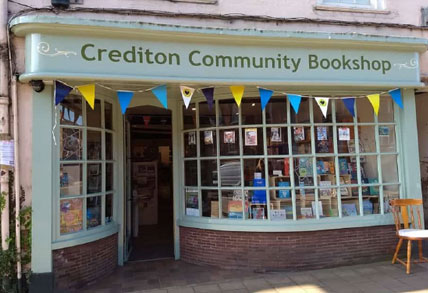

>> Crediton Community Bookshop >>

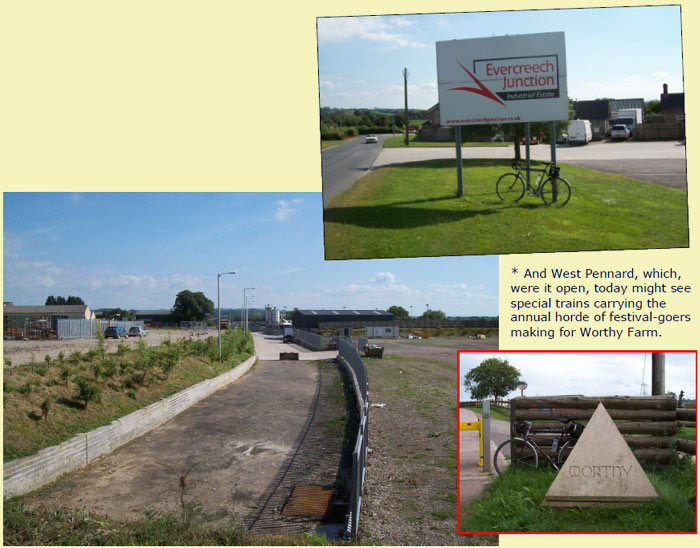

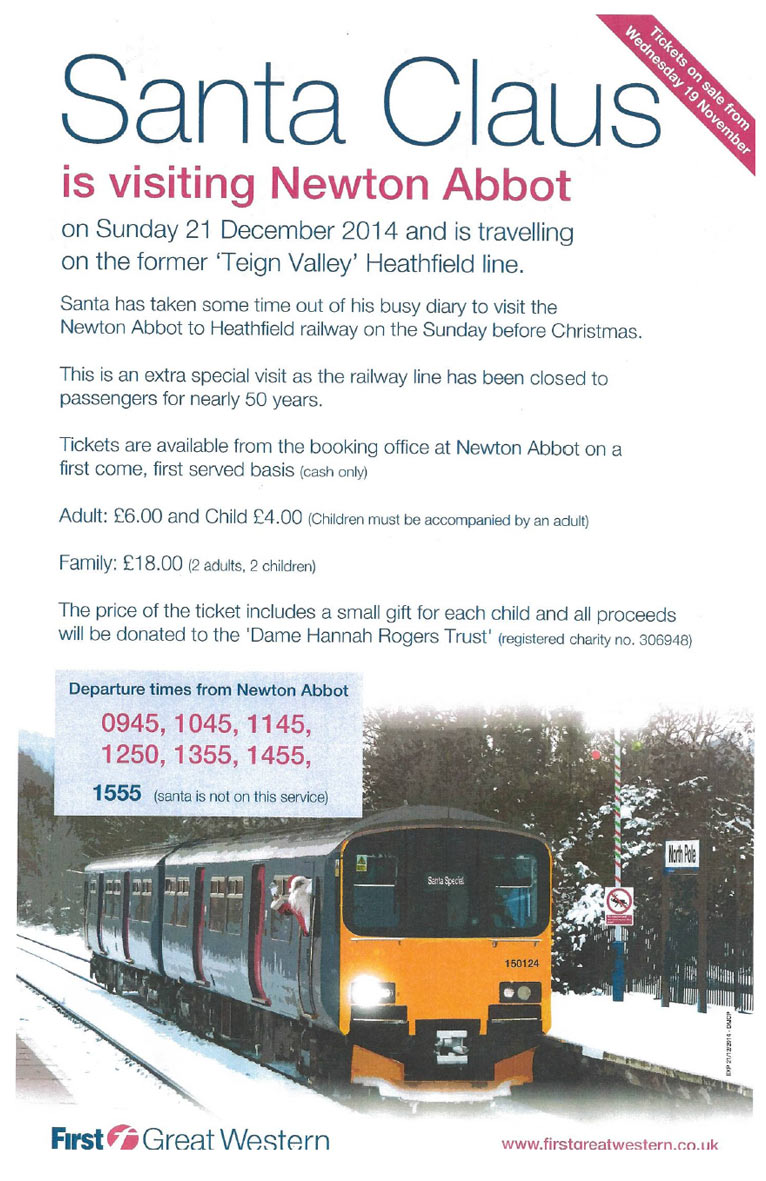

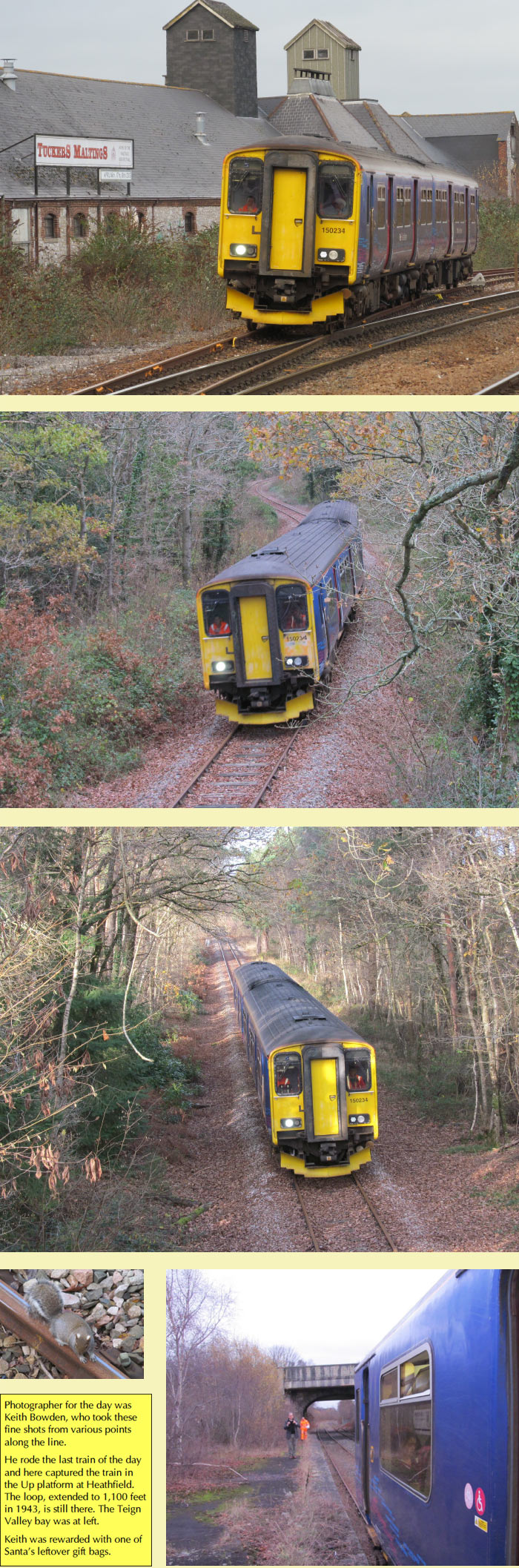

>> Heathfield - Newton Abbot Community Rail Project >>

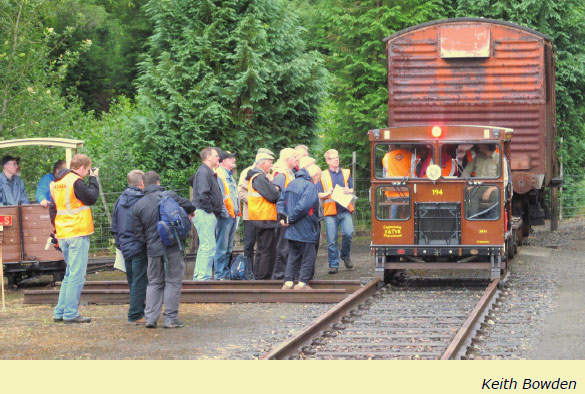

>> Visit by the Branch Line Society >>

>> The Temporary Booking Office >>

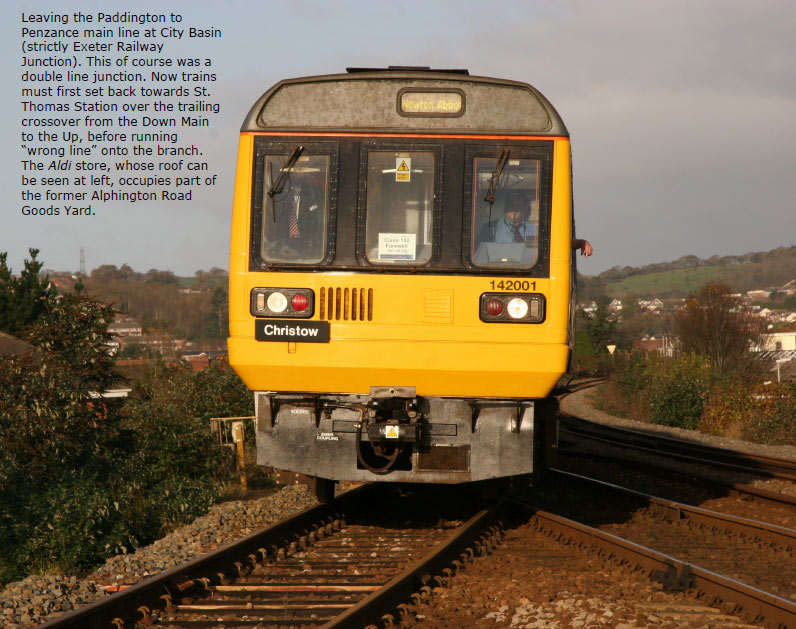

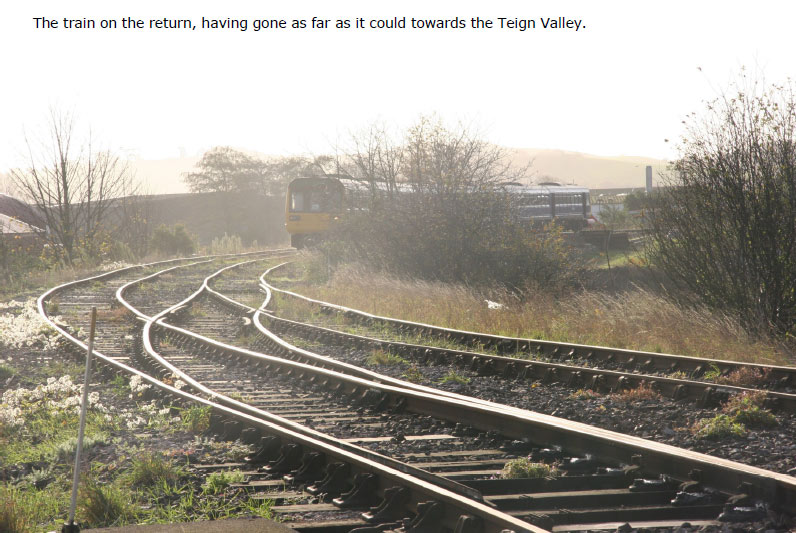

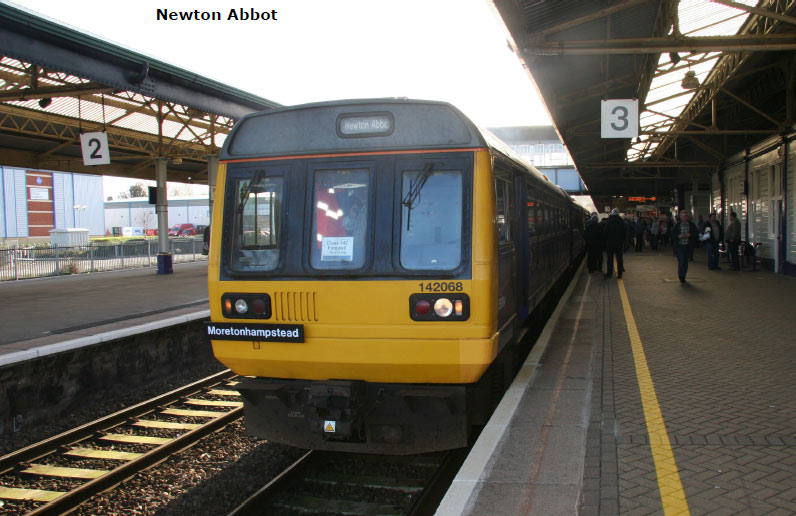

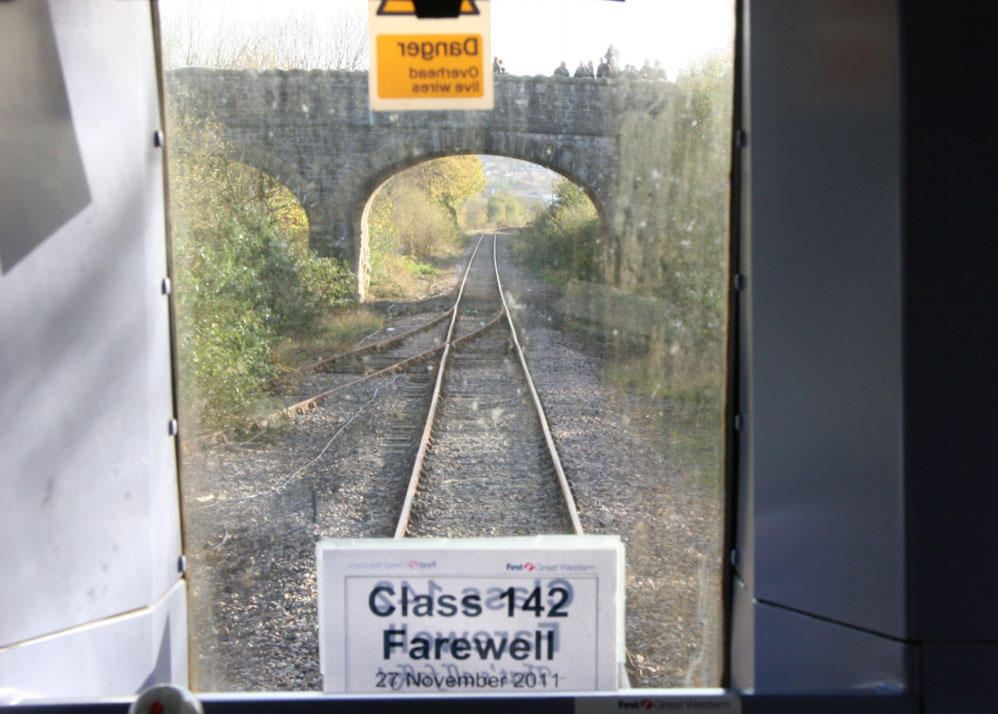

>> Class 142 Farewell >>

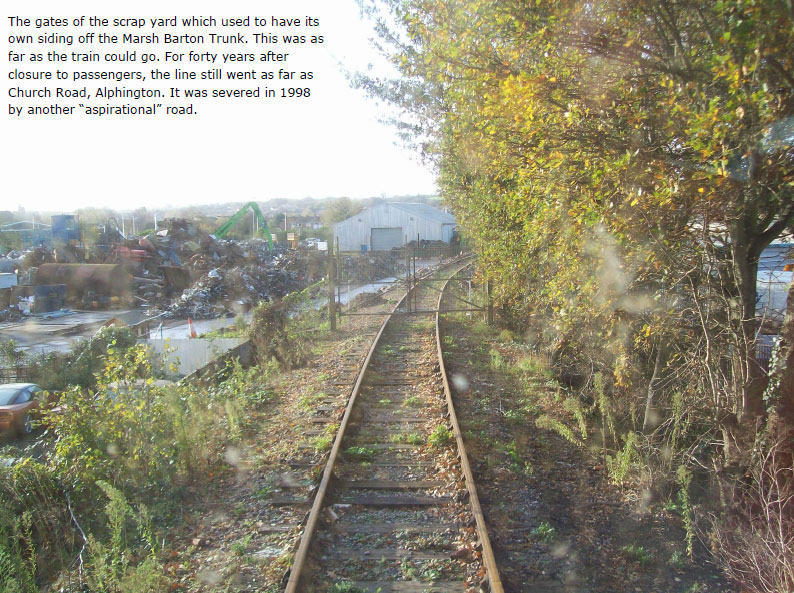

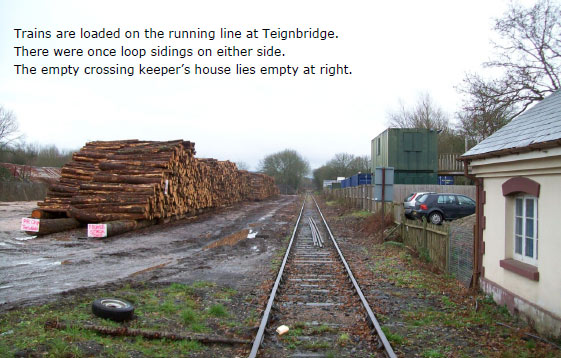

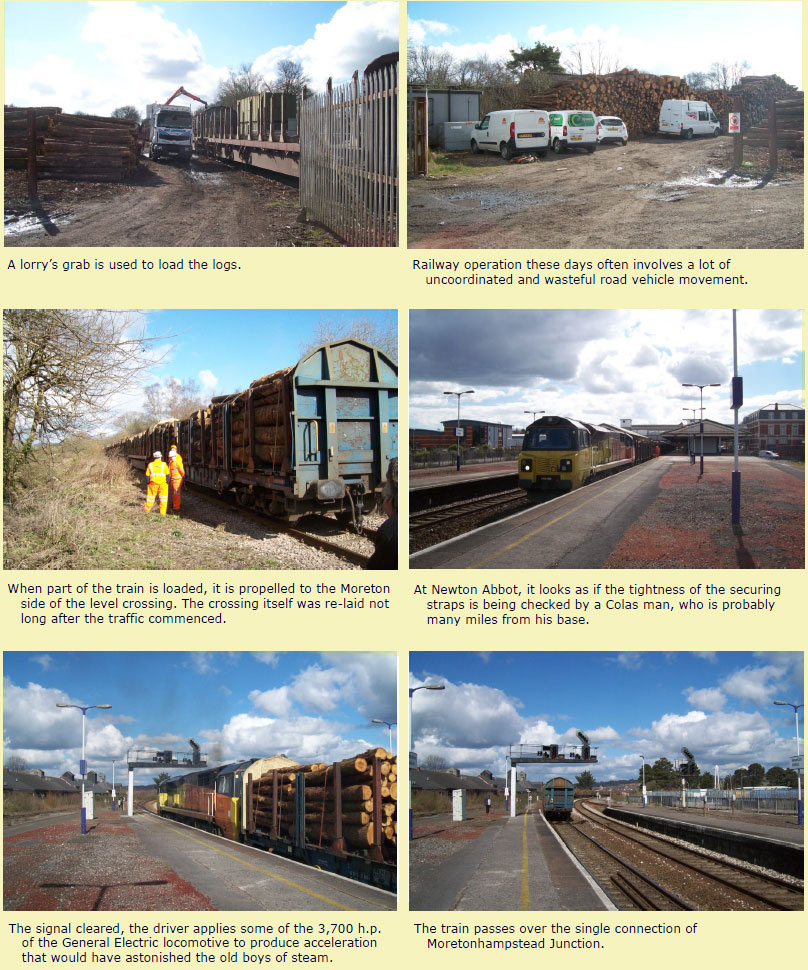

>> Teignbridge Sidings Reopened—in a way >>

>> The International Mining Games, 2012 >>

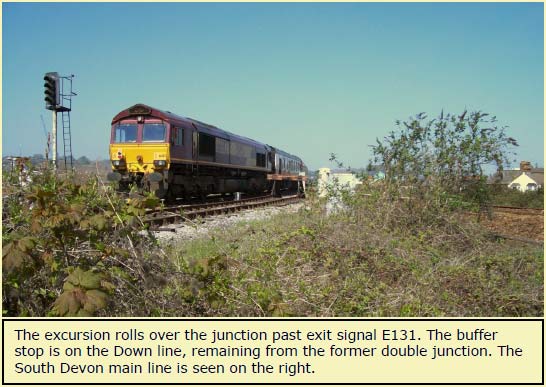

>> Cranks’ Excursion >>

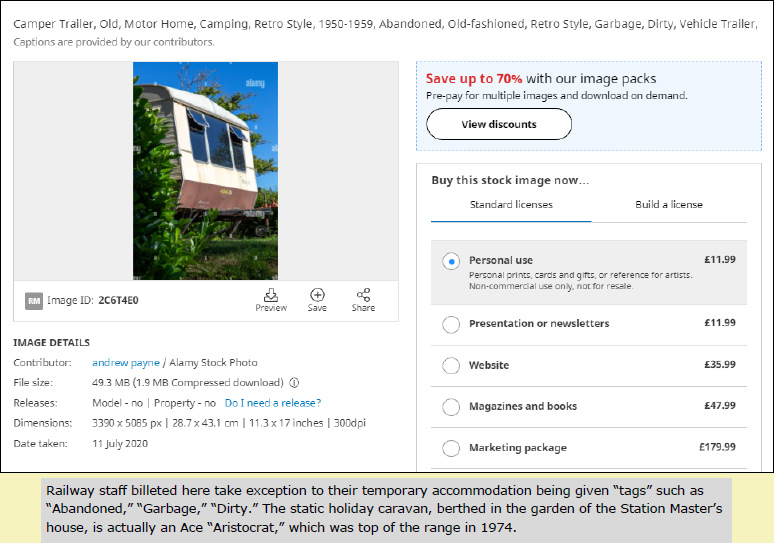

>> “This Accommodation will Never Appear in a Colour Supplement” >>

>> Study into reopening of valley line >>

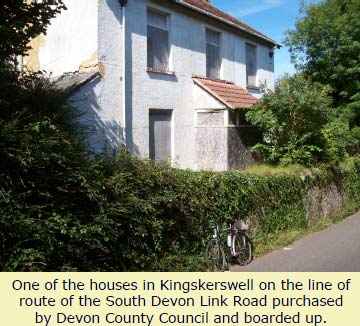

>> Kingskerswell Bypass >>

>> “Transition Tourism” >>

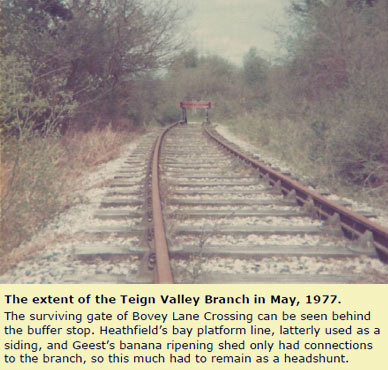

>> One of the last pictures of the Teign Valley Branch in operation >>

>> Signs Come Home >>

>> Cowley Bridge Junction >>

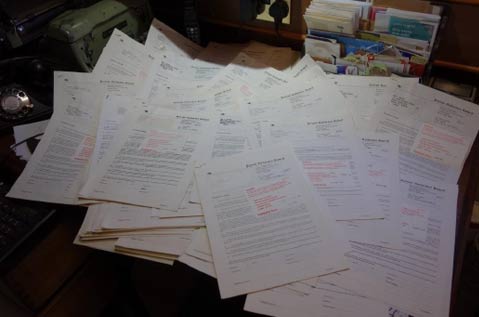

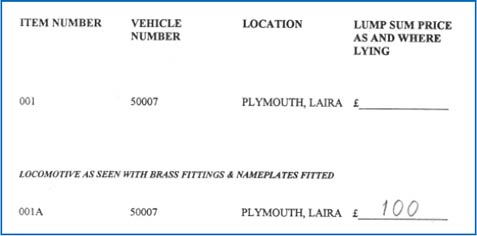

Invitations to Tender

In the 1980s, when vehicles were being scrapped all over the system, many of them N.P.C.C.S. (Non-Passenger Carrying Coaching Stock), the railway registered with the Director of Procurement for the periodical lists of disposals to be sent to Christow.

The railway was particularly hoping to purchase a CCT (Covered Carriage Truck) but most of the vehicles offered were too far away for recovery.

All rolling stock has a limited life and must be replaced after 30 or 40 years, although a huge amount of surplus freight wagons had been scrapped in the previous two decades. What made reading these lists so sad was the changing railway they revealed. The non-passenger carrying vans were redundant because of the loss of parcel post and newspaper traffic; the disposal of Mark I coaches would see the end of plentiful excursions and reliefs; and the replacement, if there were any, for engineering departments' mess and tool vans and suchlike, often elderly survivors, would be road vehicles.

Receipt of the lists came to an end in 1989 after a curt letter stated:

"With reference to your letter of 21.10.89 requesting us to continue to send you copies of our Invitations to Tender for redundant coaching stock. This has been considered but since we cannot trace your ever having purchased any stock or submitted offers your request is declined and we will cease to send you copies of our Invitations to Tender for redundant coaching stock."

Only when the files were cleared out at the end of 2025 was it found that 68 Invitations had been received, listing over 1,800 vehicles, four locomotives and 50 lots of scrap metal. In fact, the railway submitted bids for four vehicles on three tender documents. None was successful.

| No. | Code | Description | Lying | Bid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DW150289 | QQV | Staff and tool van (former BLOATER W2661W) | Taunton | £175 |

| ADW150319 | QPV | Staff coach (former FRUIT "D" W2910W, built 1939) | Plymouth | £350 |

| B461139 | ZVV | (thought to be MEDFIT) | Meldon Quarry | £250 |

| DB458756 | ZVV | ( " " " ") | " " | £250 |

When the scout went to view the last two, he was surprised to find that they were loaded with Pooley's (the weighbridge manufacturer) test weights. Sale of those would have paid for the wagons and much of the removal costs. When he learnt that the railway's bid had been unsuccessful, the scout asked the C. & W. Examiner at Meldon to give him the tip when the scrap men came for the wagons so that he could offer to buy them; he would of course say nothing about the weights. Frustratingly, the Examiner reported that the scrap men had come while he was on leave.

No one at Christow can now recall whether the railway's bid for the Class 50 English Electric locomotive was submitted.

After all the fuss, the C.C.T. that eventually came to Christow was gifted to the railway.

Yeo Valley Trust

Autumn Shareholders' Meeting 28th September, 2025

Only a month after the cashier at Christow had written a cheque for £2,000, payable to Exmoor Associates, C.I.C., the scout attended the meeting at which it was proposed, by way of a Special Resolution, to transfer shares in the Association to the Yeo Valley Trust, a charity formed to support the work of the Associates and one able to obtain gift aid and receive legacies.

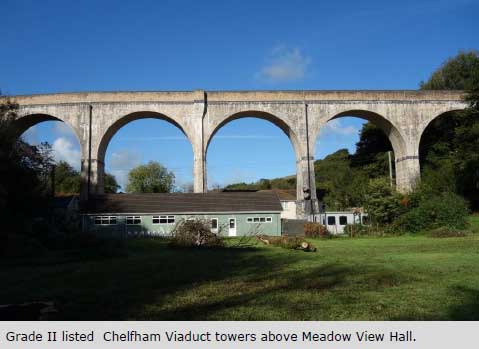

The meeting was held in Meadow View Hall, part of the newly established Growforward Project which nestles beneath Chelfham Viaduct and incorporates the old mill that used to draw power from the Chelfham Stream, a tributary of the River Yeo.

The first part of the meeting concerned Exmoor Associates and the principal business was the poll of shareholders which asked them to vote for or against the Special Resolution. The voting slips had to be checked against the list of shareholders and so the count took some time. When the result was declared, of the votes cast, 95% were in favour of the resolution. The directors would decide whether to wind up Exmoor Associates or render it dormant.

The next part of the meeting dealt with Yeo Valley Trust affairs, perhaps in a little more detail than was necessary. Before the lunch break, a rousing talk was given by long-serving railway engineer, Bruce Knights, who was itching to lay the light track which was stacked nearby; and which the scout had seen on a lorry in August, parked at the road junction.

The scout and his pal sloped off after the buffet lunch to visit the station and walk the line towards Bratton Cross Bridge. By the time they returned, attendees were dispersing.

Such has been the cooperation between the Growforward Project and the railway champions that a visitor centre is devoted to a Yeo Valley Trust exhibition, including a rolling promotional video, which is all admirably presented. There is even a small bar.

The very friendly Growforward lady, who had greeted the scout and his pal on their arrival, served them large cups of tea with biscuits. The scout chatted at length with Mike Buse, who not only revived Woody Bay but also founded Exmoor Associates, which really are wonderful achievements.

What decided the Teign Valley to back this endeavour was the talk of building a railway which would not employ steam traction, or would be most unlikely to do so. Thus, possibly a step closer has been taken to the Swiss-style electrified railway that the Teign Valley always thought should serve Lynton and Lynmouth, long ago dubbed "Little Switzerland."

Getting Back on Track

Reviving the Teign Valley Line

In January, 2024, Prof. Geoffrey M. Hodgson of Dunsford wired the railway:

"This weekend I was in discussion with Andy Swain (Liberal Democrat councillor for the Teign Valley) and Mark Wooding (Liberal Democrat Parliamentary Candidate for Central Devon) about the possibility of re-opening the Teign Valley line. They are both keen to investigate this. I came across your highly informative website."

The railway replied:

"When Younger-Ross was prospective parliamentary candidate for Teignbridge, I often used to lobby him regarding the branch lines. There was no interest shown by Lib-Dems at the time.

"As it's very nearly ten years since the wall was breached at Dawlish, I am bringing my account up to date. I chuckled at a bit of my report on Network Rail's roadshow at Langstone Cliff."

"And there they were, the vain and the vacuous, lining up to deliver their well-rehearsed, but quite meaningless , lines. Even standing as close as he could, the scout found it hard to catch what Tory Clone, Painted Doll and an M.P. who had bought luxury furnishings for his London flat at taxpayers' expense, had to say—as if it mattered."

"The Okehampton revival gave the impression that government was seriously going to roll back Beeching, when in fact it will be joined by only a handful of other projects. In a mini mania, groups in Devon are pressing for the return of rail services to Bideford, Bude and Tavistock. I support them, all the while understanding the institutional deadweight that stands in their way."

Professor Hodgson is Emeritus Professor in Management at Loughborough University, London; Editor in Chief, Journal of Institutional Economics; President of the Darwin club for Social Science; Secretary of Millennium Economics Ltd.; Chair of the Teign Valley History Group; founder of the World Interdisciplinary Network for Institutional Research (WINIR).

Prof. Hodgson produced a draft report, with the option of a shared-use path instead of a railway, or as an intermediate stage, and circulated it among the group, which included Jan Rayment, a party officer, and Charles Eden, the Chairman of Holcombe Burnell Parish Council.

Mr. Wooding replied:

"An excellent document. My only question is does setting out an option for a cycle-way detract from the main point about reinstating the railway?

"Whilst this might constitute a fallback position I wonder if tactically it is better to maintain the focus on reinstating the rail line?"

Prof. Hodgson explained his reasoning:

"Andy's original suggestion to me was for a cycle way only. My response was to suggest to him a cycle way as a step towards re-opening the railway. When I researched the document, I became more and more convinced that the Teign Valley Railway is the best solution to the Dawlish problem (which will NOT go away). Colin Burges' Teignrail website is particularly persuasive on this, as is the paper with projections on future storm impacts at Dawlish.

"One advantage of keeping the cycle way as a transitional step, is that two big expenditures at each end would be postponed. These two big expenditures are (1) the Alphington-Ide rail link, which would involve some rebuilding at the A30 roundabout, and (2) the construction of the rail link aside the A38 from near Chudleigh to Heathfield. But the bridges would be rebuilt, and the tunnel repaired, making a continuous cycle route from Ide to near Chudleigh. Then, perhaps after the inevitable further closures of the main line at Dawlish, we could push for a completely restored Teign Valley railway.

"On the other hand, as you suggest, there is an advantage in pushing for the fully restored rail link now. This is a clearer and more focused objective. My worry is that the big expenditures at each end would stall the project."

The railway wired the "Friends," pointing out the difficulties in making a walking and cycling path, and questioning its real value.

"Establishing a cycle—or, properly, a shared-use—path in preparation for railway reinstatement would in fact result in little advantage.

"A path from Halscombe Lane to Trusham, which is about all that is possible, with detours onto main roads between Perridge (assuming Sir Harry would allow use of the Perridge carriage drive) and Horrowmore, and between Greenwall Lane and Ashton, would involve the land which was the easiest to obtain or the landowners who were the most amenable. Compulsory purchase is seldom used for leisure trails.

"Perridge Tunnel could be made safe by shotcreting, like Whiteball, but this would further reduce the rail structure gauge in what was a notoriously tight space.

"The tunnel would have to be lit between 0500 and 2300. Structural lining using concrete segments, which is what is really needed, would be far too costly for a cycle path to bear.

"The one missing bridge which could justifiably be replaced is Cotley Lane and this would be done with a lightweight span like those near Moretonhampstead.

"Once a path had been made, users would not want to lose it. Vague ideas of reinstating the lines between Barnstaple and Bideford, Okehampton and Tavistock, and Bodmin and Wadebridge were immediately opposed by walkers and cyclists, even though most come by car with bikes or dogs to an access point, whence to treat the trails as linear parks.

"With the exception of my 100 yards, nothing has been done; and I predict that nothing will ever be done.

"A Sustrans scout who joined by 2003 commemorative walk from the main line junction to Christow concluded that the route was only of value for heavy rail.

"The railway would be rebuilt under a Transport and Works Act Order with full powers."

In a reply to Prof. Hodgson, commenting on the first draft of his report, Andy Swain wrote:

"When we first discussed this, I was interested in the possibility of a cycle track, and that was my goal. There is as Geoff said the possibility of a walking track, requiring less engineering at the lost crossings, but also potentially a less valuable resource to justify the expense.

"To be honest the idea of reopening the railway had not crossed my mind, and I tend to agree with Colin that forming a cycle track or footpath, is exclusive with reopening as a railway."

Four links to relevant films on the railway's YouTube channel were sent to the group, along with itemized costs of the work on the main line, totalling £218-million. These costs were later referenced for Prof. Hodgson.

"In 2014, Network Rail priced a double line of railway along the Teign Valley route at £470-million, with a 66% contingency uplift. The price I got, assuming no N.R. involvement, was £180-million for a reinstated single line. Even N.R's. over provision had a cost-benefit ratio of 0.29, the best of the options. The "Borders" line in Scotland was given the go ahead on 0.5 (50p back for every pound spent) and has been a runaway success.

"I stand by what I wrote under "Coping with Perilous Exposure" in 2017."

"The danger is that far too much money will be spent on this line and that vastly better resilience than it has now will never be achieved. With worsening conditions, it is possible that no real progress will be made and all the while there will have been no attempt to create route diversity, once a great strength of the British railway system.

"Short of tunnelling behind the cliffs, no amount of work will make this route invulnerable: it only needs to fail in one place to stop trains. As this railway said after the Dawlish Débâcle in 2014: "The challenge is to ensure that the existing line has the greatest possible resilience, but to have readily available an inland diversionary route between Exeter and Newton Abbot."

Prof. Hodgson published a final version of his report, which made no mention of a path, on 14th February. It is, of course, merely an academic exercise but nonetheless welcome and useful.

Bridge Strike

Christow Station

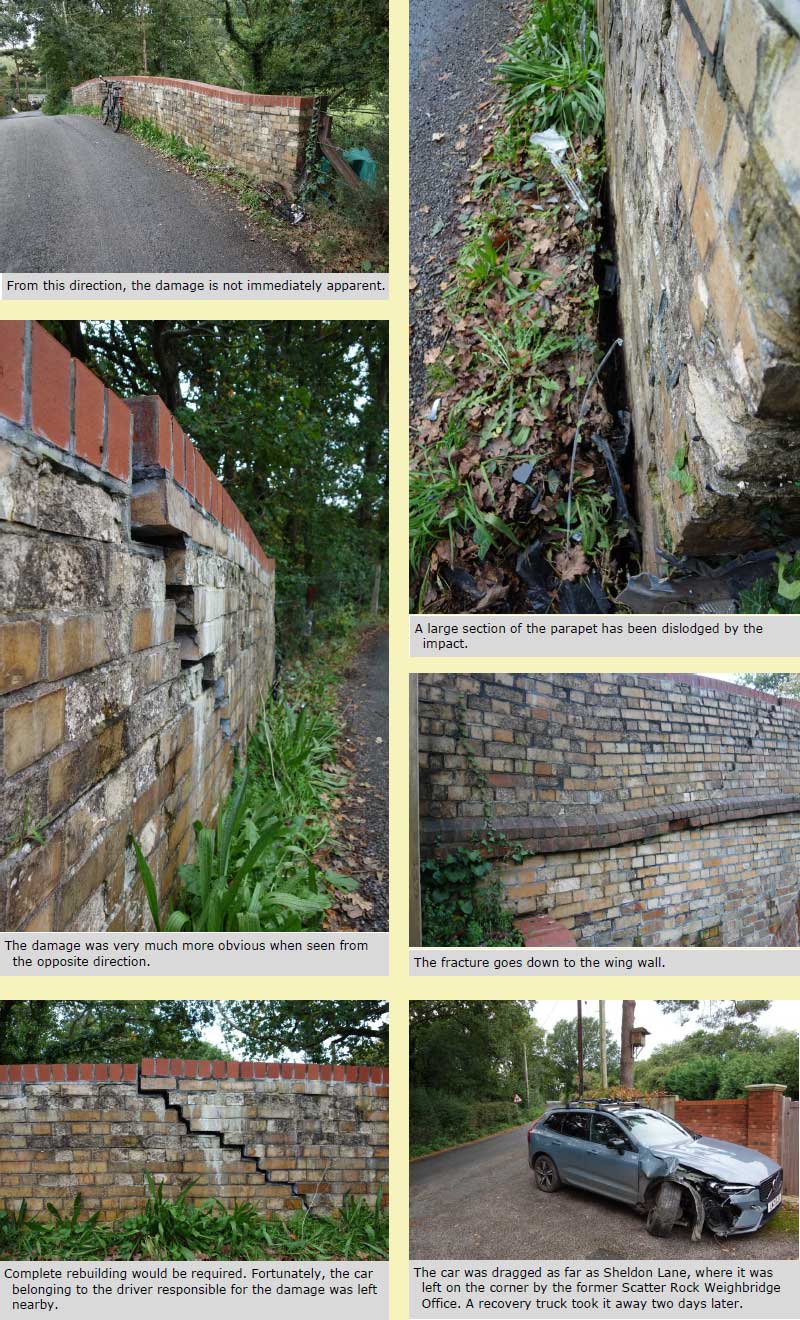

Late in the evening of 19th October, 2023, a car struck the parapet of Station Bridge and caused severe damage.

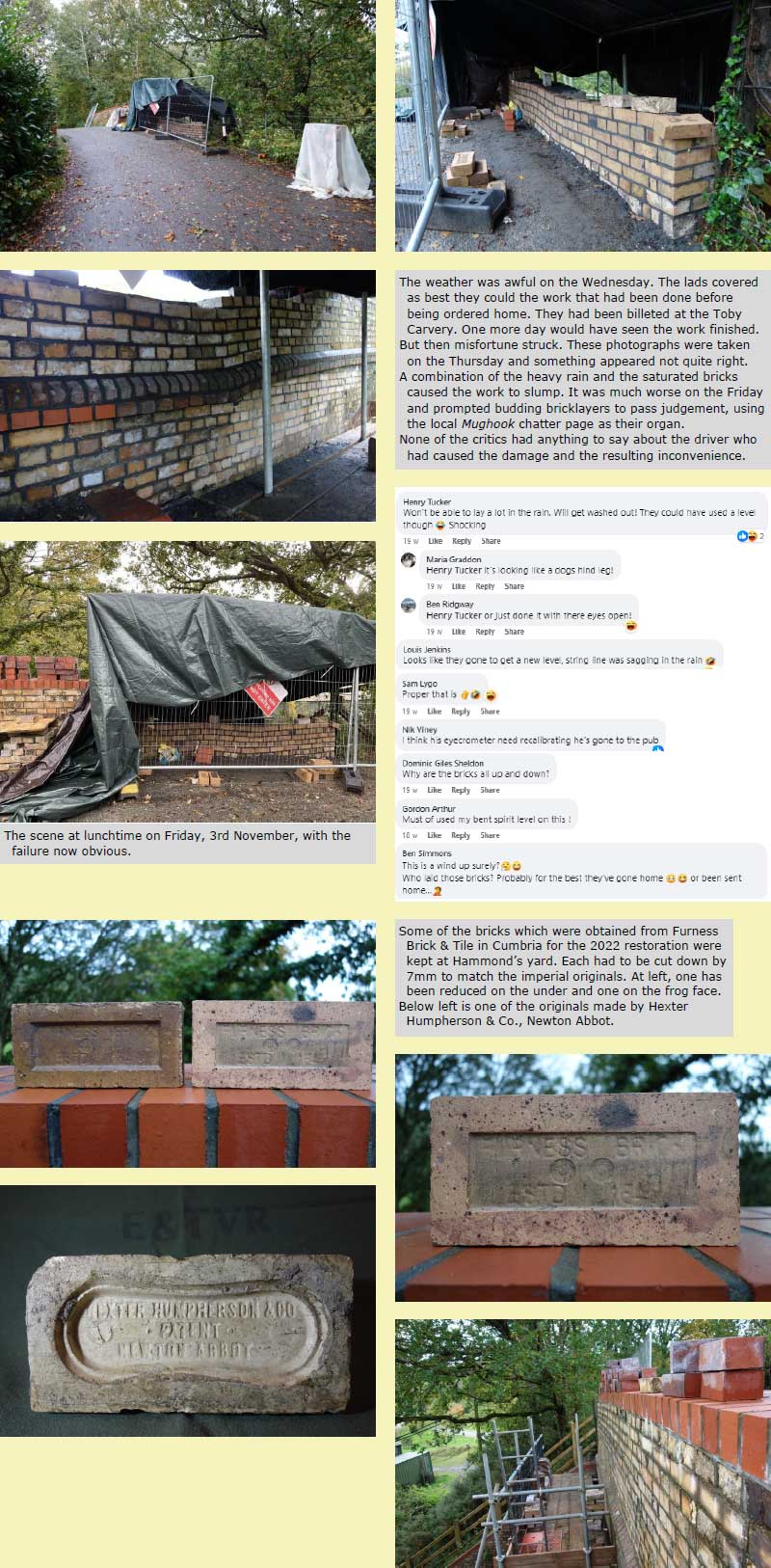

Only the year before, £70,000 had been spent by Historical Railways Estate sympathetically repairing the structure.

An outpouring of anger was vented on the local chatter page, with a few suggesting that the driver may have consumed alcohol.

The crash was reported by the railway to the local beat bobby, P.C. Hawkins (13114) on 24th. He replied, advising that he could not create a crime report from a wired message. Others had the patience to use the proper channel.

On 25th, justified by five years of correspondence on the subject of drink-driving, a message was sent to the Police and Crime Commissioner. A reply came on the 1st November from Erica Harris, Customer Service Support Officer, advising that the matter had been passed to the Head of Road Safety within Devon and Cornwall Police for his attention. She added: "He has shared this with his team and asked them to take some actions such as patrolling in Christow over a period of time ... "

The following morning, no less than Superintendent Adrian Leisk (34247), Head of Road Safety, got in touch.

"Thank you for your email expressing concern around Devon & Cornwall Police's approach to drink driving in the Teign Valley."

"We have an active operation (Dragoon) to identify and take action against those who pose significant risk on our road network. This includes drink and drug drivers.

"We have a No Excuse team, consisting of a Sgt and 5 constables based in South Devon who use marked and unmarked cars, equipped with Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras to tackle those above drivers who pose a risk on our road network.

"If you are happy to provide any specific intelligence around the drink driver, I will ensure that this is submitted on the system and shared with the No Excuse Team Sergeant."

The railway was able to provide some "specific intelligence."

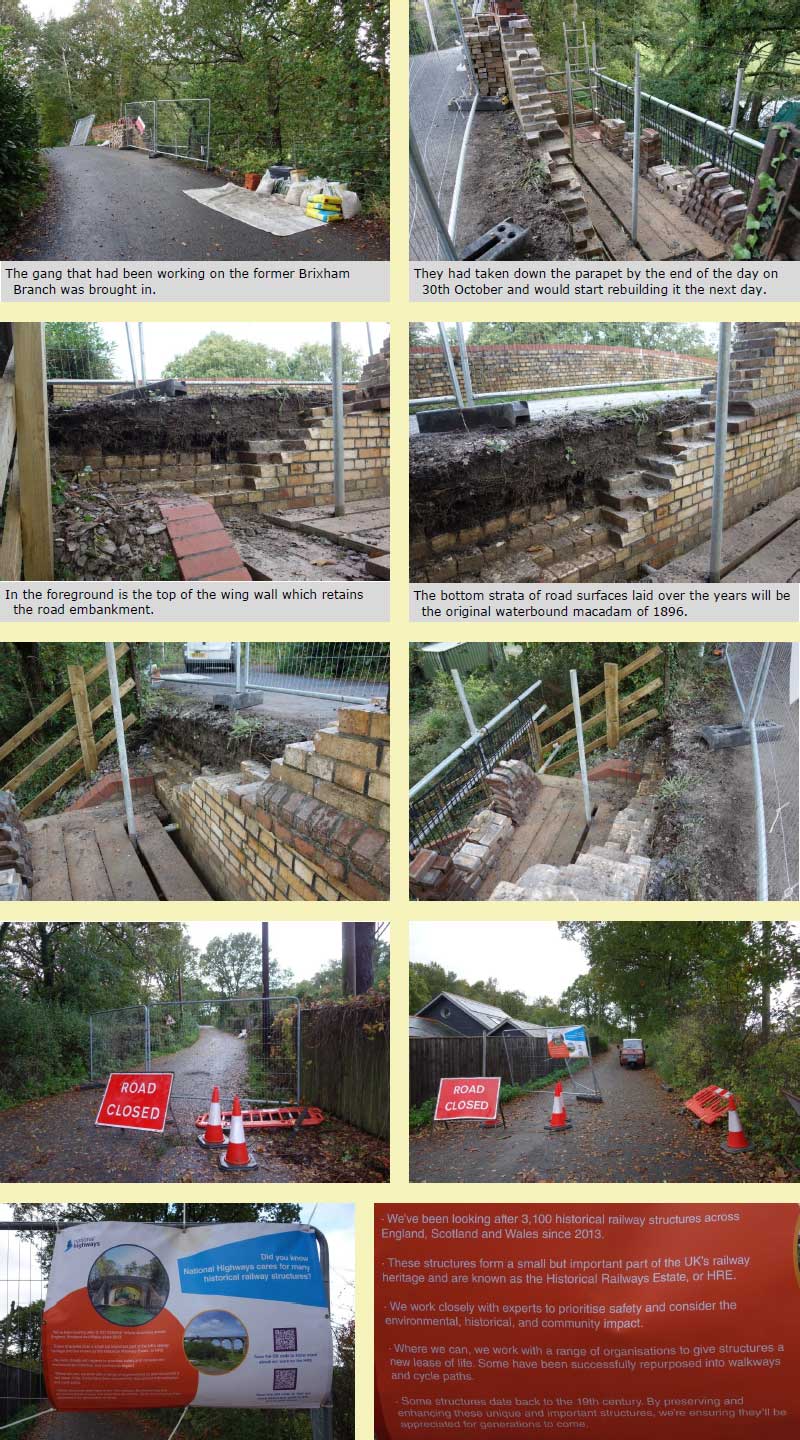

Who says that authority never acts quickly? A few days after the incident, an engineer came to examine the bridge and only eleven days after it was damaged, framework contractor, Hammond from South Wales, on behalf of the authority, closed the road for a fortnight so that repairs could be done in safety. This caused a great deal of inconvenience, not least to bus passengers, as the No. 360 had to be diverted.

After the fiasco with Great Musgrave in Cumbria, where a retrospective application to infill the bridge was refused, National Highways was anxious to rehabilitate itself and seemed to have chosen Christow Station Bridge as an exemplar of its newfound, responsible approach.

The gang returned on Saturday and took down what had been done. On Monday, 6th November, the work was finished and the road was reopened.

February, 2024: A Freedom of Information Request was submitted to National Highways through the web channel: "Please advise the amount that was spent repairing the damage caused to a parapet of this bridge after it was struck by a car on 19th October, 2023. Please advise whether the amount is being claimed from the car driver's insurance."

The answer came on 19th: "The repairs cost £25,472.98 and the process is being followed to recover this from the driver's insurance company."

March, 2024: This information was sent to Superintendent Leisk, along with the observation: "The other regular offenders I thought may have shown some caution after this prang, but it appeared that drink-driving carried on being a laughing matter locally."

No reply was received.

Followers of the "Teign Valley Railway" Mughook page were told how much the repairs cost in a brief post, finishing with: "It is noticeable that the valley mob, which is viciously critical of cyclists legitimately using the public highway, is silent about the area's habitual drink-drivers."

B.R. Totems

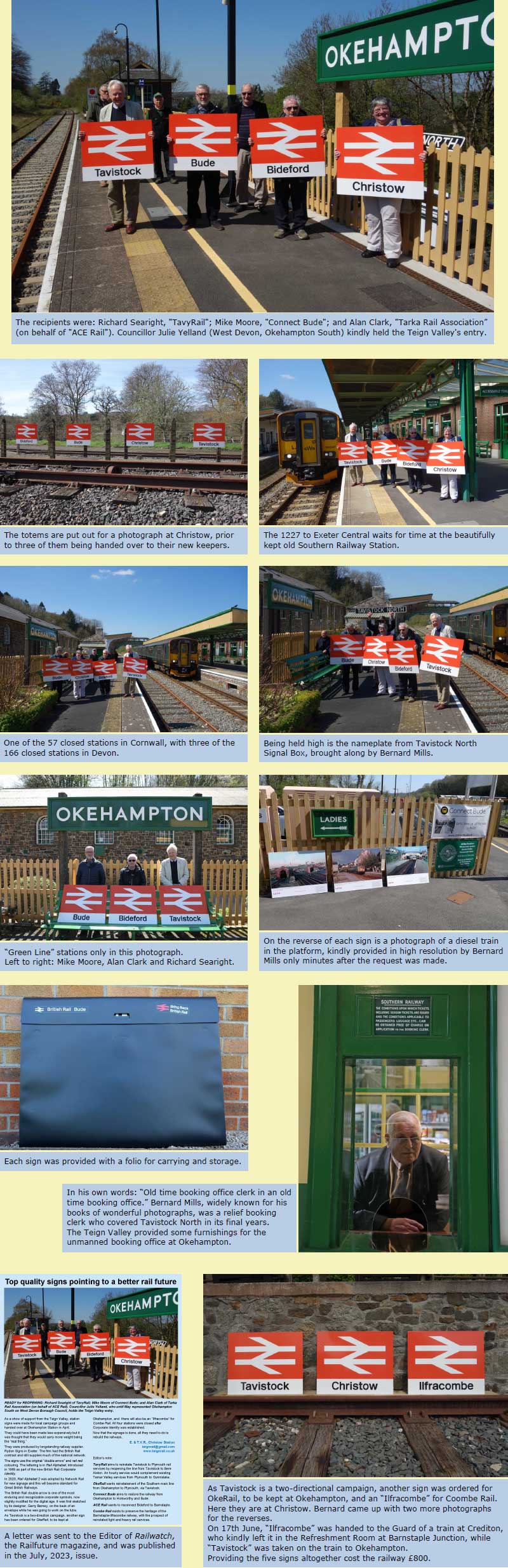

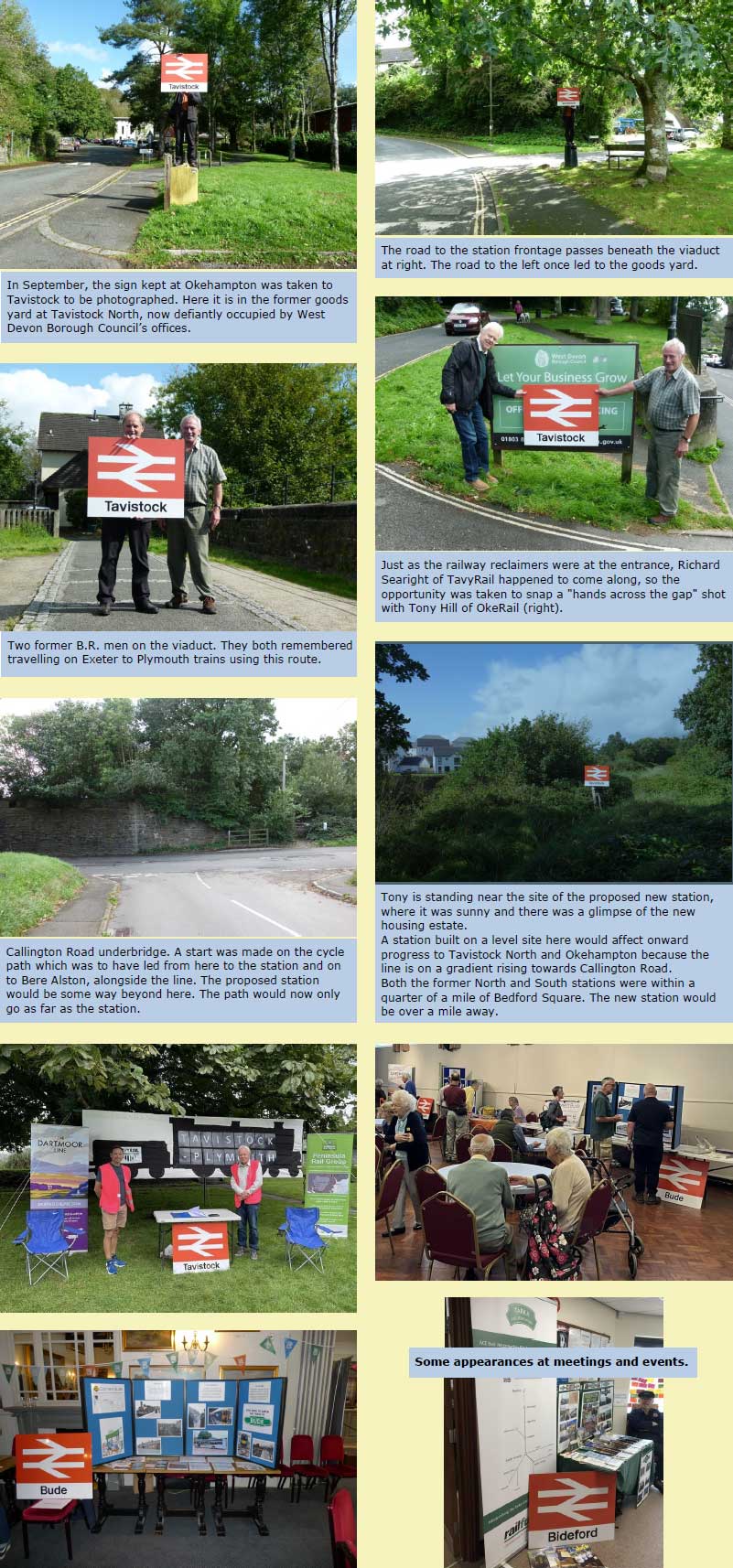

When the Teign Valley procurement officer visited longstanding railway supplier, Rydon Signs at Pinhoe, he saw the large orders wrapped and ready to be dispatched to places on the national network and felt it rather feeble that he only wanted one small totem. So, as he entered the design and print room with Dave Rossetter, the very helpful General Manager, he boldly blurted out: "Make me four."

The signage for Marsh Barton was seen propped against a wall while Matt the designer put the "double arrow" on the computer screen with "Christow" beneath it. Dave asked what the other stations were to be and was told with only slight hesitancy: "Bideford, Bude and Tavistock."

As a show of support from the Teign Valley, the three signs were handed over to representatives of the local campaign groups at Okehampton Station on 20th April, 2023.

The signs are intended to be used as "stage props" and in publicity. They could have been made less expensively but it was thought that they would carry more weight being the "real thing."

They have the original "double arrow" and rail red colouring. The lettering is in Rail Alphabet, introduced in 1965 as part of the new British Rail Corporate Identity.

In 2020, Rail Alphabet 2 was adopted by Network Rail for new signage and this will become standard for Great British Railways, if it is ever born.

The British Rail double arrow is one of the most enduring and recognizable corporate symbols, now slightly modified for the digital age. It was first sketched by its designer, Gerry Barney, on the back of an envelope while he was going to work on the tube.

All four stations were closed after Corporate Identity was established. Now that the signage is done, all they need to do is rebuild the railways.

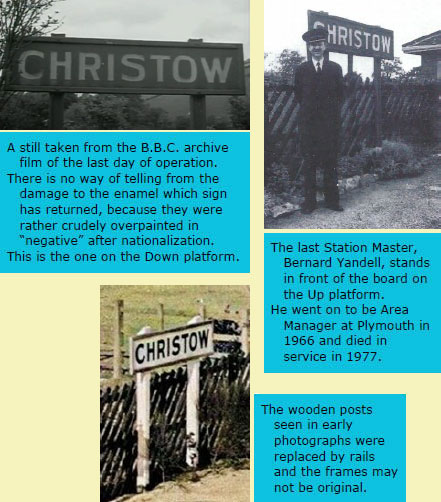

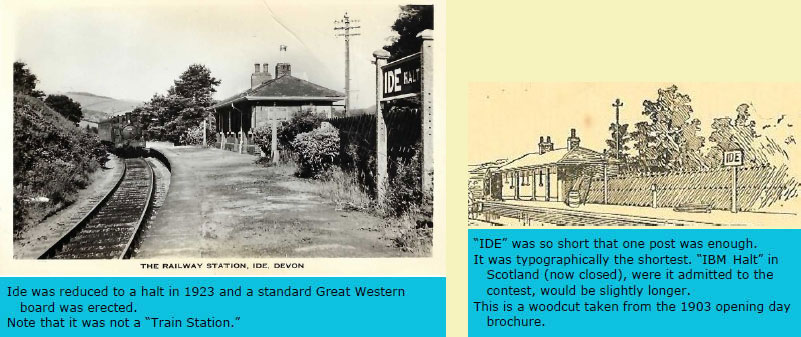

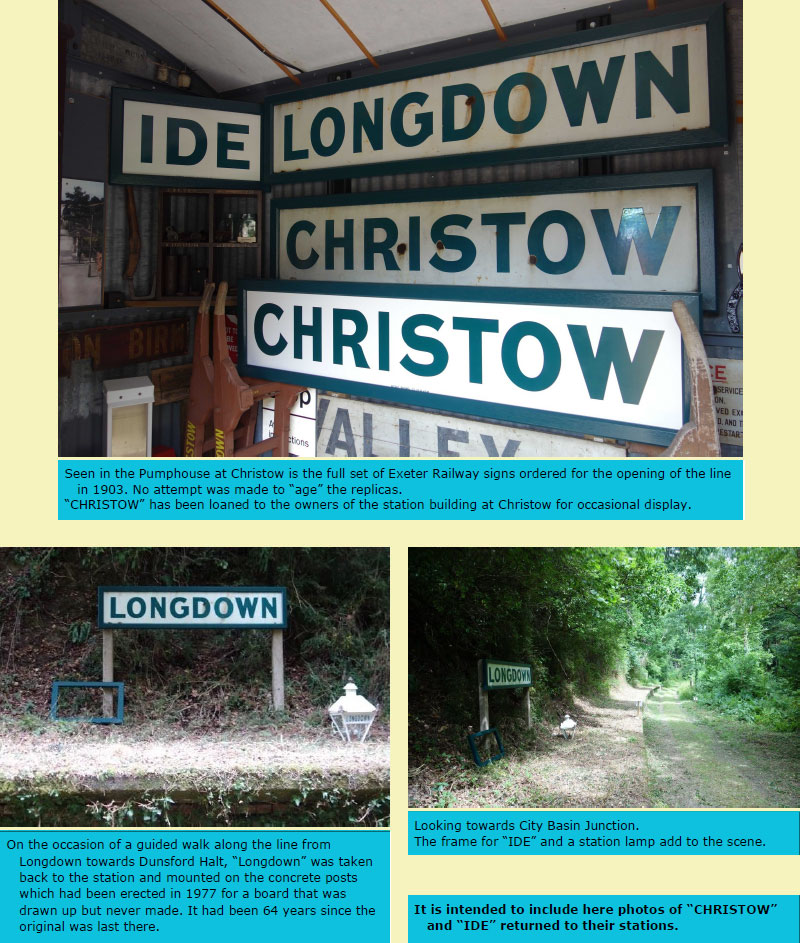

Running-In Boards

The story of how two original running-in boards had returned to the Teign Valley is told in full under "Signs Come Home."

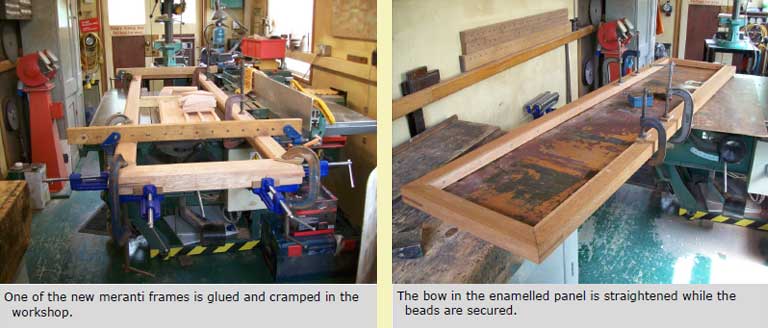

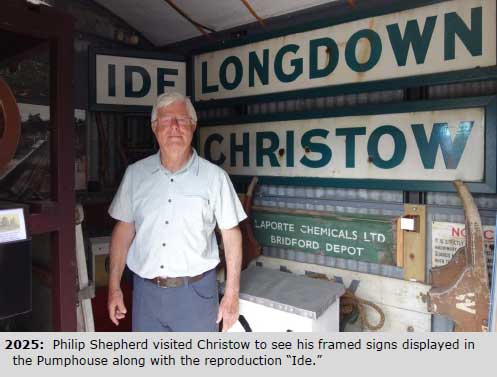

Using the only close-up views of "CHRISTOW" as a guide, simple frames were made out of meranti. The mouldings were beefed up a little to correct the bowing of the enamel panels, possibly caused in the kiln.

Lengths of moulding were left over, enough, it was estimated, to make an "IDE," once the shortest station name in the country.

And still there was a bit to spare, enough for a short side of another "CHRISTOW." As making this would complete the set ordered by the Exeter Railway for the opening of the line in 1903, some more meranti was ordered.

The replica signs have powder-coated aluminium panels with lettering cut from vinyl, printed to match the originals. They were then varnished to give the appearance of enamel. If more panels were made, the printing method used by Rydon Signs to make the B.R. totems would be used. This gives the lettering a slight relief.

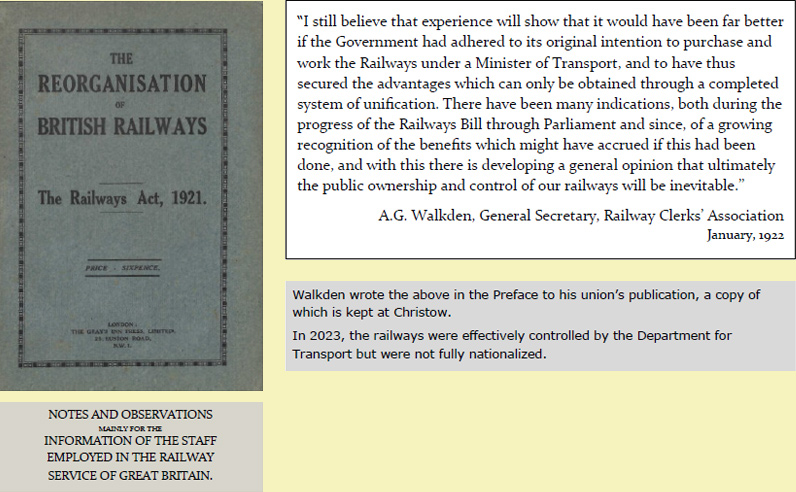

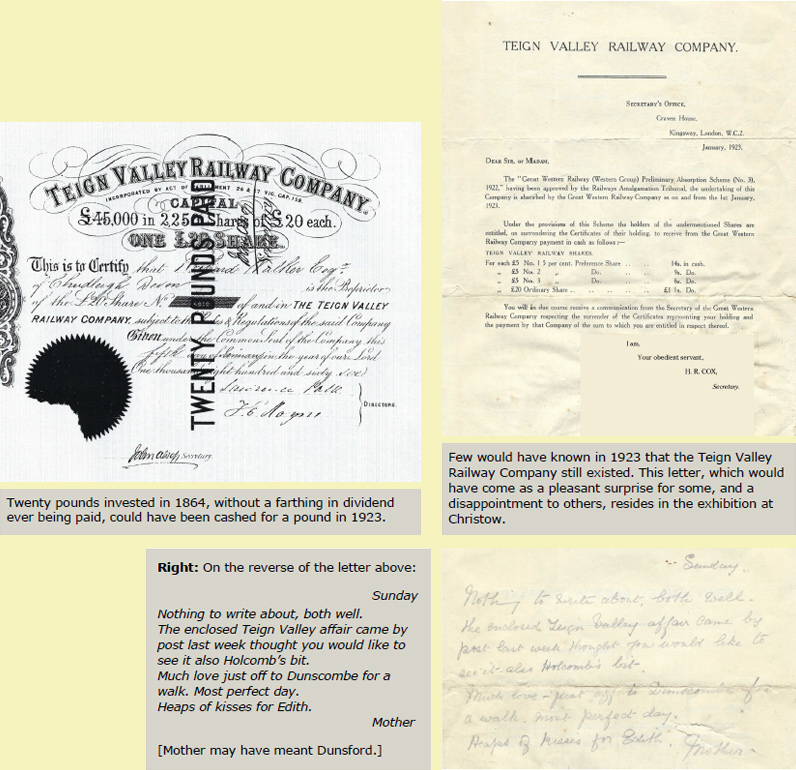

One Hundred Years since the Grouping

Who has not come across a £5 Premium Bond at the back of a drawer, perhaps dating from childhood? Anyone who bothered to check would likely find that it had never won a million—or even a pound—since it was issued.

At least Premium Bonds are redeemable at face value, unlike share certificates.

The beginning of the "Big Four"

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the railways were taken under government control and this was not relinquished until after a means of reorganizing the system and its ownership had been decided, which would allow the supposed benefits of wartime unification to continue.

As a compromise, instead of nationalization, the Railways Act of 1921 established four group companies which were to absorb nearly al the existing British railways, owned by 119 companies. The Great Western Railway was the only original name to survive the grouping.

The other three, London, Midland & Scottish, London & North Eastern, and Southern, absorbed very extensive systems with old names. Of the 26 "constituent" companies, five were grouped with the Great Western, the largest being the Cambrian. The remainder, "subsidiary" companies, included small, local concerns like the Teign Valley and Exeter, often only remembered on paper.

Compensation for shareholders was based upon lines' earnings in 1913, the last year for which figures were available. This suited the Teign Valley company very well because 1913 had been its best year.

The Exeter company, however, would not settle up without an argument. That it caused the Great Western more trouble than any other may have been partly due to the Exeter being a young company, whose line had been operating fewer than twenty years. The company made the case at the Railways Amalgamation Tribunal that, due to its burgeoning stone traffic, revenue was considerably in excess of the pre-war level. The Tribunal upheld the position of the E.R. by recommending a higher value for the company than the Great Western had been prepared to pay.

This was accepted and the way and works of the Exeter Railway, along with those of the Teign Valley Railway, became part of the Great Western as from 1st July, 1923.

Both the Teign Valley and Exeter companies had eventually managed to service their highest priority debentures, and holders of these received G.W.R. 4% debenture stock at par. The rest of each company's value in shares or cash was distributed according to proportions decided by the boards.

Neither company ever paid any dividends to ordinary shareholders, who had long been resigned to the knowledge that their stock was near worthless. The descendants of plump parsons and wealthy widows, who, in the 1870s, had eagerly bought £20 T.V.R. shares, received 21s. (£1.05) in cash for them in 1923. Likewise, Exeter Railway ordinary shareholders received one twentieth of their stocks' nominal value in cash.

The E. & T.V.R. continues the noble British tradition of pouring money into the bottomless pit of a railway project without any hope of a return.

Nationalization finally came, after another world war, in 1948. Forty-six years later, the state threw the railways back to the private sector and created a disintegration that was far worse than existed before 1923.

B.R. ceases to be

The fag end of nationalization has finally been snuffed out.

Further to the brief item on BRB (Residuary) Ltd. included in the Perridge Tunnel pages, it can now be written that the organization was disbanded in September, 2013, and its functions transferred to a number of existing bodies.

Most of the Historical Railways Estate (formerly known as the Burdensome Estate) was passed to the Highways Agency (of all people). Other responsibilities and liabilities were taken on by London & Continental Railways Ltd., Network Rail, the Rail Safety and Standards Board and the Department for Transport. Included in the transfer were the quaint "Rights to Wreck," a residue of the railways' complete transport system.

Thus the people's railway that began life in 1948 vested with 20,000 locomotives, 55,000 carriages, 1¼-million wagons, 12,000 lorries, 123 ships, 35 hotels, 650,000 staff, over 8,000 stations and enough track to stretch more than twice around the equator, very nearly all financed by private investment with very little help from government (arguably, the railways had actually subsidised the state), ended up in 2013 with its remaining baggage being thrown out or given away like the few tatty possessions of a poor, forgotten soul after a funeral.

The Railway's War Effort at Christow

Eighty years later

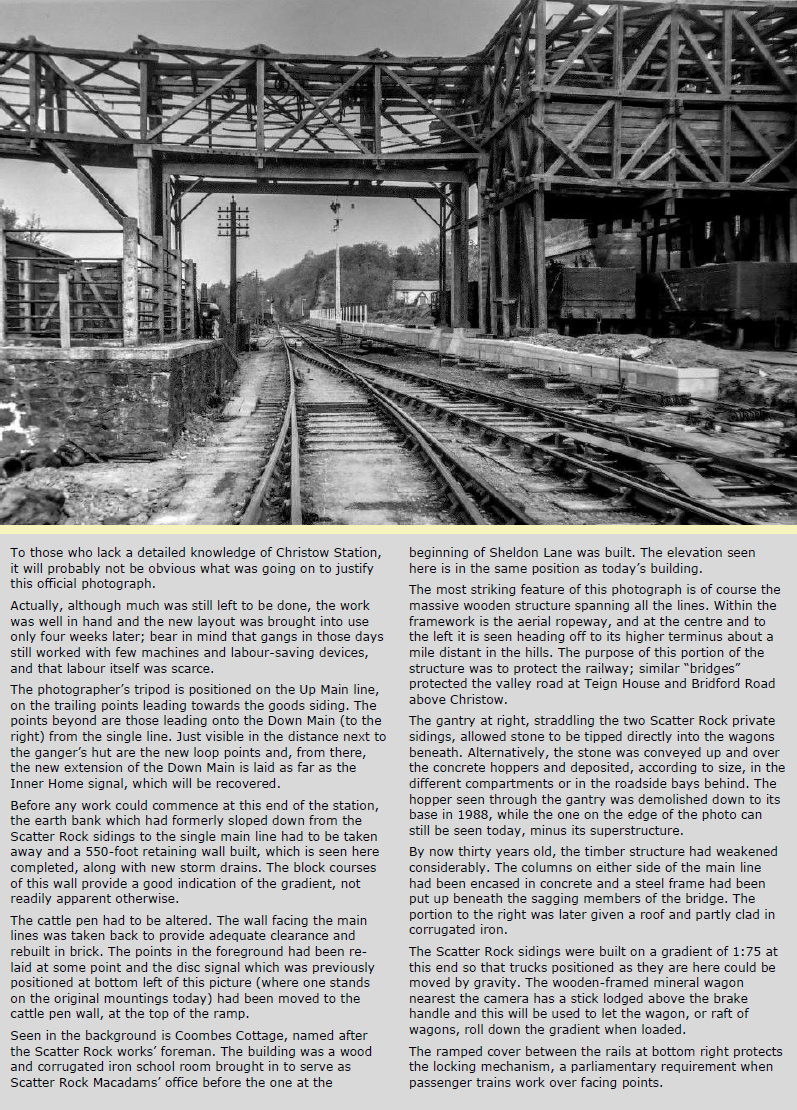

Anyone could be forgiven for thinking that this official new works' photograph merely recorded the normal expansion of railway facilities, in the days when rail transport was the predominant mode.

Nothing in the photograph reveals that the world was actually in the grip of war, which brought death and destruction from the skies above England.

Enemy bombers were often to be seen flying low over the sand bar at Dawlish Warren and up the Exe estuary, on their way from occupied France to attack Exeter or perhaps other targets.

The main line which they flew right beside, a vital supply route for the naval base at Devonport, was naturally considered vulnerable and, for this reason, the Teign Valley Branch (like many other secondary lines on the G.W.R.) was kept open continually, night and day, from 1941 to 1945. The branch's usefulness in an emergency—even a peacetime one—was severely limited because of the track layout at stations, and so the line was included in a government-funded programme of "Insurance Works" for increasing the capacity of diversionary routes.

By the time this photograph was taken, the tide of the Second World War was turning in favour of the Allies. The Russians had taken back Stalingrad in January; the Axis forces in North Africa would shortly surrender; Japanese advances in the Pacific had been checked. And in the Atlantic, the U-boat menace was being countered, which would enable the American build-up to commence for D-Day.

In not much more than another year, then, the threat which prompted this work at Christow was to pass.

The Works

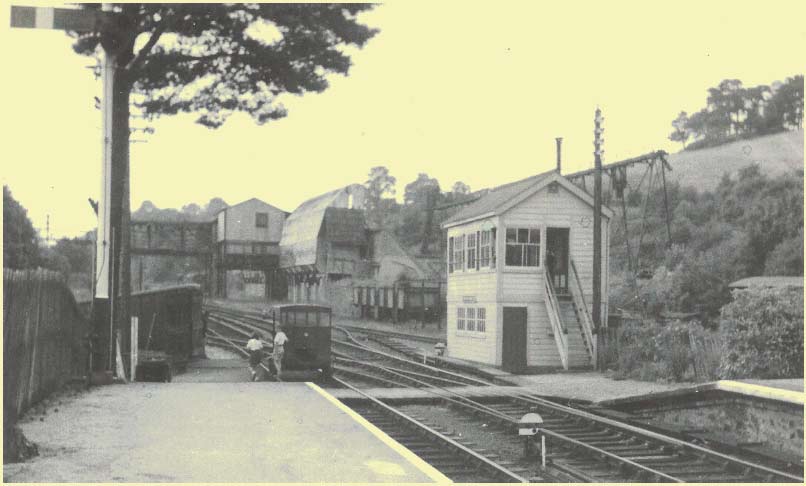

Nowhere on this inland route between Exeter and Newton Abbot could a fifteen-coach train make an uncomplicated crossing with one travelling in the opposite direction. The only passenger loop on the Teign Valley section was at Christow and it was meant only for the light traffic of a country branch line. Furthermore, even at the junction with the Moretonhampstead Branch at Heathfield, where there was a long loop, two diverted trains could not cross without shunting because of the junction layout.

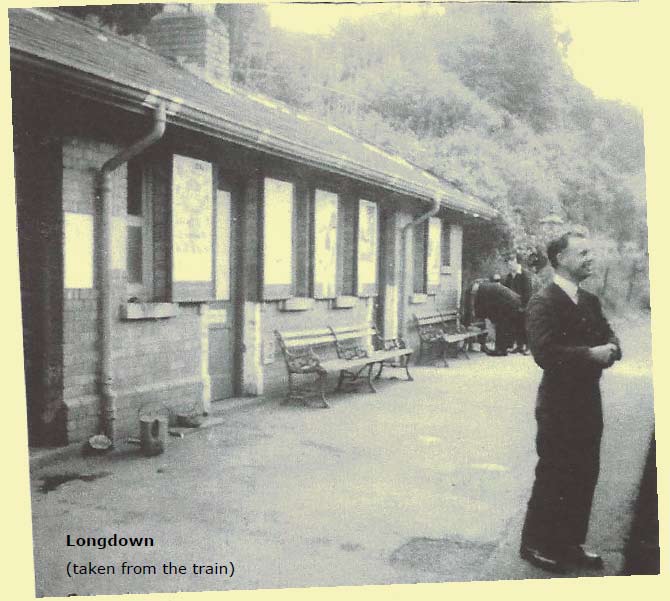

To remedy this incapacity, the 1943 improvement works entailed a new Down goods loop at Longdown, an extended loop at Christow, conversion of the goods loop at Trusham and the laying in of a double junction at Heathfield.

The total estimated cost was £31,047, of which £6,669 was to be spent at Christow.

Beeching Did Not Shut the Teign Valley Branch

Sixty years since the "axe" was wielded

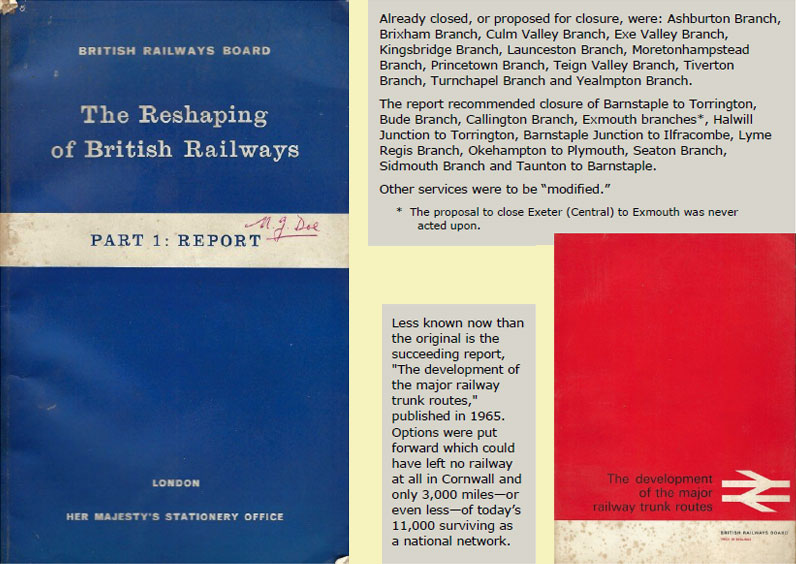

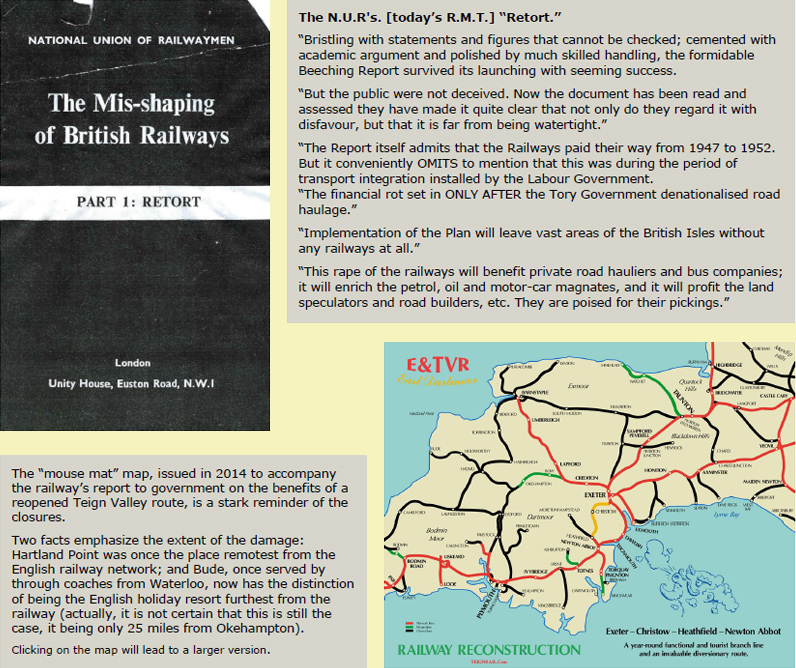

By the 1950s, it looked as if many branch railways had had their day and there was a mood of resigned acceptance as steps were taken to close them. When the closure programme became one of full-scale retrenchment in the early 1960s, the public was reassured by the simplistic analogy, "pruning will encourage new growth."

But as time went on, and the point at which contraction would produce a viable industry somehow could not be found, it became clear that the railway was like a giant organism and that no part of it could be harmed without affecting the whole. Those who embarked upon the process of "reshaping" made the mistake of isolating parts of the railway, not realising that all of its activities were to some degree interlinked and inter-dependent; this is charitably assuming that the pruners did not act with a hidden purpose.

On 27th March, 1963, the report which came to be known as the "Beeching Axe" was published.

The railways had been making cuts in the 1950s—the closure of this branch in 1958, and those to Princetown (1956), Moretonhampstead (1959) and Ashburton (1958), provide ample local evidence—but Beeching at a stroke said that territory and activities where the railway could not pay their way should be abandoned.

Cynics and, increasingly, real historians, claim that destroying the railway's universal service was necessary to justify the massive expansion of road transport which ensued.

The report was not concerned with environmental impact; it took no account of the social and cultural value of the railway system. Beeching did not have to look to the future and explain how the usurper would be powered when the era of cheap oil was over. And no one has ever reckoned up how vast was the capital thrown away.

In Devon, the destruction began in earnest with the closure of the Princetown Branch in 1956 and finished with the withdrawal of passenger services between Exeter and Okehampton in 1972.

Over 400 route miles and more than 200 stations were lost from the network in Devon and Cornwall alone.

A facsimile in hardback of the original report is available from the Gift Shop at Christow Station.

All the Stations includes lists of the existing and former stations in Devon, Cornwall, Somerset and Dorset.

Lord Beeching was interviewed in 1981 by the B.B.C. in Hindsight.

Part 5 of a ten-part Channel Four series, broadcast in 1984: Losing Track: Beeching

"Creeping closures": This Week, 1969.

A poet gives his view of road and rail in this film clip.

The Railways Archive has made available scanned versions of the Report, which is in two parts:

The Reshaping of British Railways - Part 1: Report

The Reshaping of British Railways - Part 1: Maps

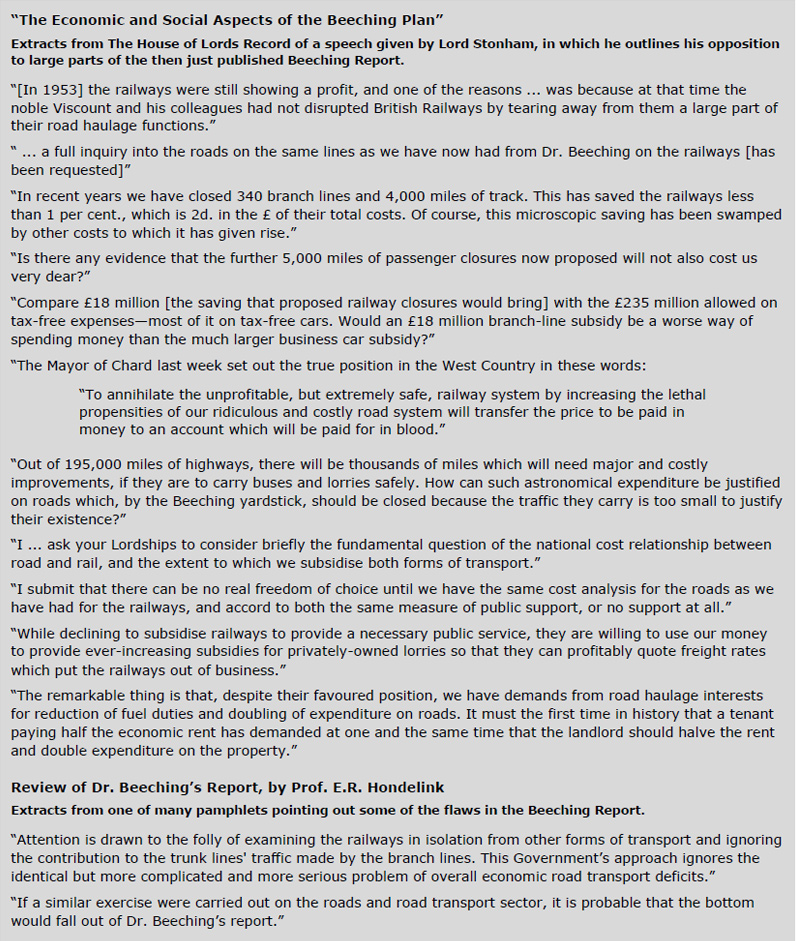

The Archive also has these critiques of Beeching's work:

The destruction wrought by the "Reshaping" was greatest at the extremities of the railway system. What did it mean for the ordinary railwayman?

Stephen Derek went to work in the Divisional Superintendent's Trains Office at Exeter Central in 1960, when it was very busy with the organization of a wide range of complex functions, delivered in the traditional Southern style.

Well within the decade, he saw the loss of almost the entire network beyond Barnstaple and Okehampton, the closure of all except the Exmouth Branch in East Devon and the main line reduced to a secondary, singled route. Was there the slightest indication that this was to come in 1960?

"I can certainly say that when I joined in 1960, there was no hint that it would change beyond all recognition within ten years. Train services were still being expanded: the Cleethorpes service; extra locals, Exmouth-Budleigh; the 5.45pm Exeter Central to Exmouth non-stop "business express"; Surbiton-Okehampton Car Carrier; the accelerated ACE [Atlantic Coast Express] How we just thought it would last."

Christow Station Bridge

More on the cost of keeping disused railways disused.

Scaffolding was erected in September, 2022, and work started on maintenance which it was said would occupy a specialist gang from South Wales, accommodated in Exeter, two weeks.

On 4th November, after seven weeks' work by contractors, the site was deserted.

https://www.highwaysindustry.com/national-highways-give-bridge-a-yellow-brick-facelift/

The bridge was actually completed in 1896 by the Exeter Railway. The original road around it continued to be used, with a level crossing of the contractor's line from Teignhouse Siding. The money had run out and work was stalled. The bridge was to stand for seven years before the first service trains ran beneath it.

The second image in the article above is reversed: the steps are on the left, the Downside.

The unique wording of the potted history of the line is taken from "The Railway" found on these pages.

https://www.devonlive.com/news/local-news/historic-devon-road-bridge-back-7855262

On 8th March, 2023, a letter was sent to Hudson House, York, requesting the costs of work on the bridge to be revealed under the Freedom of Information Act. When no acknowledgement was received, the letter was repeated on 28th March. A newspaper article explains why nothing was heard from National Highways.

https://www.yorkpress.co.uk/news/16421348.demolition-nearly-finished-york-office-site-hudson-house/

In a Freedom of Information Request submitted through the web channel, two questions were asked of National Highways Historical Railways Estate: How much has been spent on the bridge since 2000? How much of this was spent on the repairs done in 2022?

The answers were: £105,020.49 and £69, 269.13.

Response from National Highways: Christow Station Bridge EXR 8.06

Work like this would normally have gone unreported. It is thought that the publicity given to this structure was very much the authority trying to redeem itself after the fiasco in Cumbria.

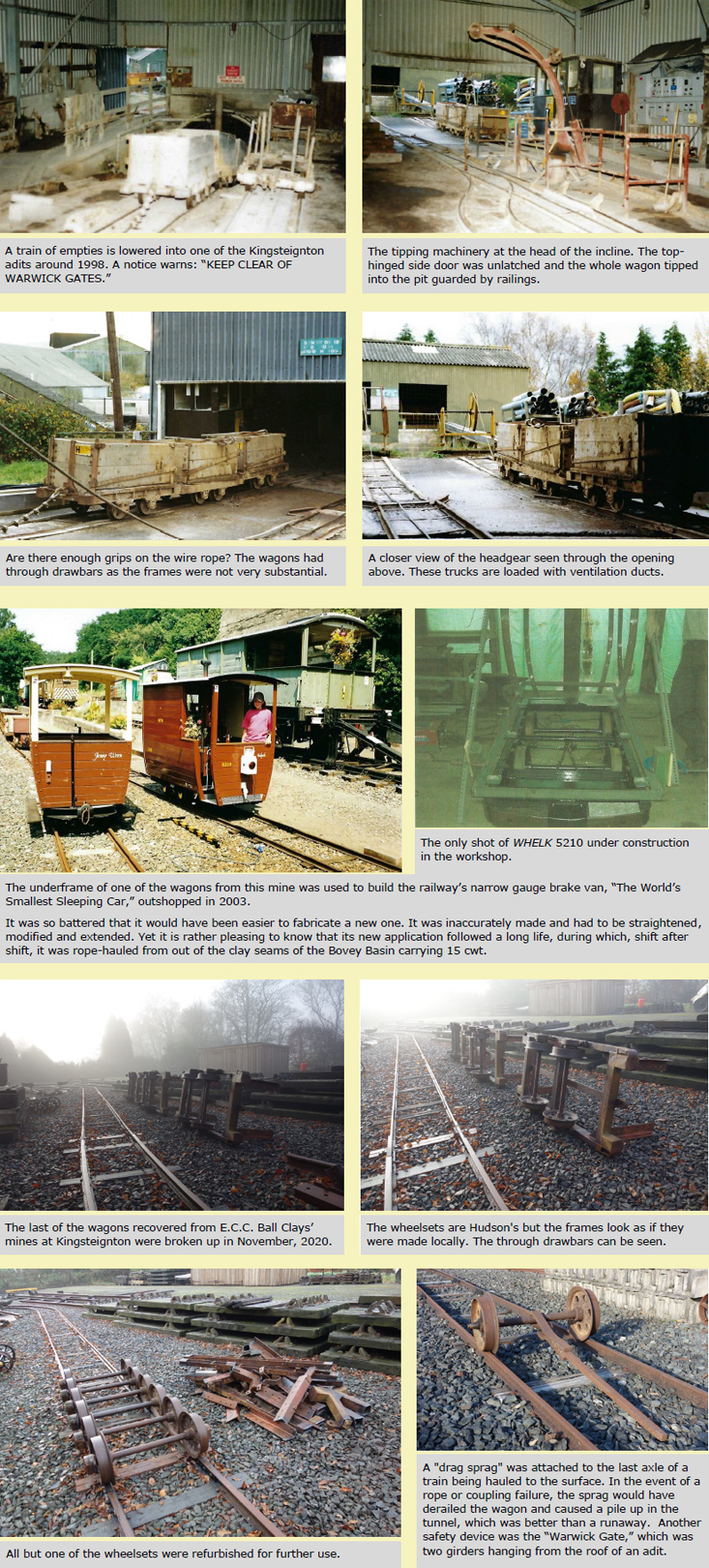

Ball Clay Mining

A seldom seen and lesser-known South Devon industry

Fascinated by what could be glimpsed from the road of the two-foot lines leading underground, in 1990 the Teign Valley scout went to the Watts, Blake, Bearne & Co. works office and spoke to the Mine Manager, who very kindly arranged for the scout to be taken individually on a tour.

Jim Wormald, who had managed enormous coal mines in South Africa, described Kingsteignton as "user friendly." There was no dust or water and it was comfortably warm.

The adits were arranged "herringbone" fashion, with side tunnels leading from a main drive. One man controlled the winch at the surface; trains were raised up a covered incline to the upper floor of a steel-framed building, where the trucks were tipped. Another man was at the underground junction, where a winch hauled the train from the side tunnel being worked. At the face, two men worked the crawler cutter, which fed the clay back to load successively a train of four trucks.

Every two feet or so, another steel rib, in two parts, was installed and three-inch thick larch boards were inserted. All these materials and the ventilation ducts were brought, and then recovered, using adapted trucks.

A surveying line in the roof kept the tunnel on course; the scout was shown a plan of all active and old workings over a very large area.

Once the train was loaded, the men had to wait for it to return empty from the surface.

The Mine Foreman also took the scout to see more-modern 2'-6" wagons being discharged automatically at the head of another adit. One of these wagons and a cutter, donated by Ball Clay Heritage, stand on the roundabout at the end of Clay Pits Way in Kingsteignton.

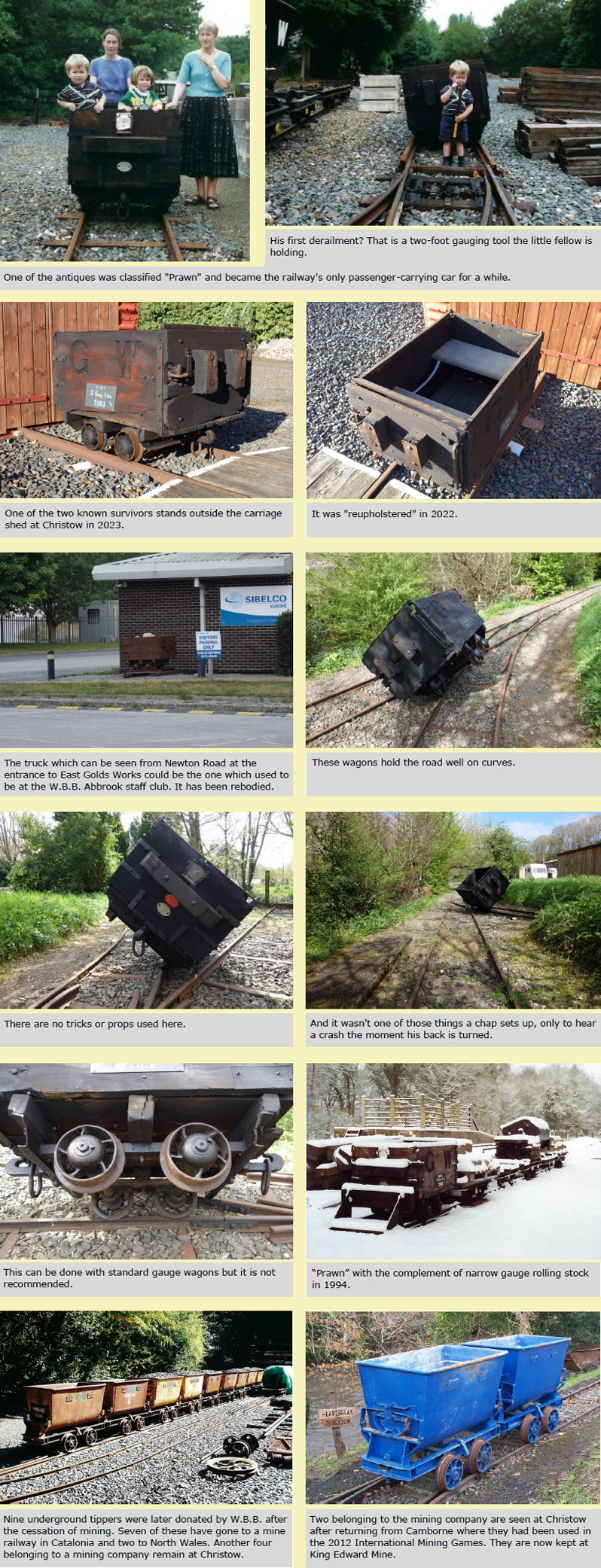

Afterwards, the railway was given two of the antique wagons which the firm had used before the steel tippers were obtained.

A brief description of Ball Clay Mining accompanies one of these wagons on open days.

Mining enthusiasts in Catalonia: Mountain Mine

Nearby, E.C.C. [English China Clays] Ball Clays also mined the Bovey Basin using quite different equipment. Operation had ceased by the time the railway recovered a large quantity of wagons and track sections; the latter were quickly put down along a path by the river.

Only one wagon underframe survives at Christow but the rails by the river were later released from their flat steel ties, straightened and re-laid on steel and wooden sleepers.

The Purbeck Mining Museum is at Norden Station on the Swanage Railway.

The Ball Clay Heritage Society is based in Newton Abbot.

The International Mining Games were held in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, in 2023.

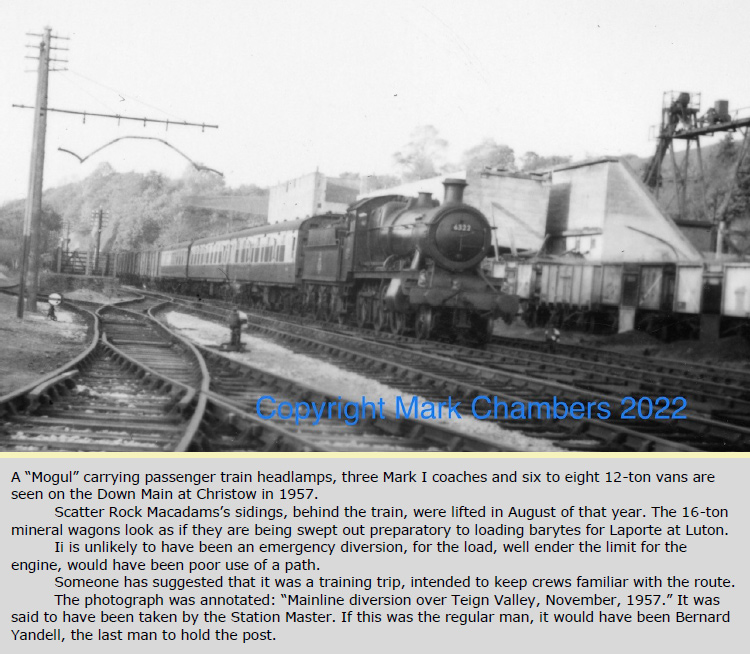

Main Line Diversion

Not, unfortunately, the "Limited" or a U.S. ambulance train

Until recently, no photograph of a diverted train had ever come to light. But then Mark Chambers, the well known Teign Valley enthusiast and historian, grandson of Revd. Wilbert Awdry, no less, acquired this and has been kind enough to share it.

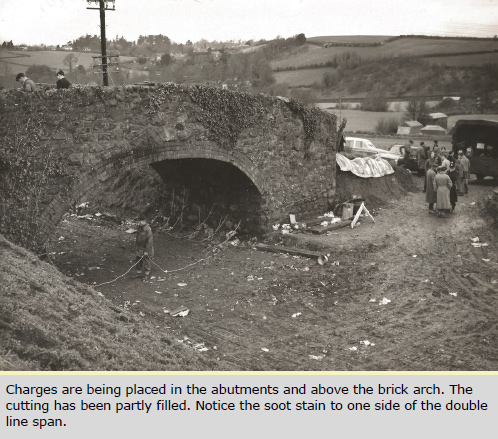

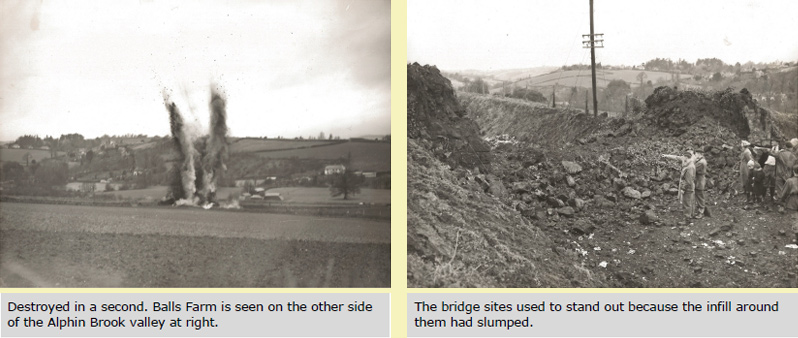

There it was, gone

Blowing up a bridge

Less than 20 years after government had paid for improvements to the line, Royal Marines were called in to blow up the bridges. This is the second of the two accommodation bridges between Ide Lane and Polehouse.

The demolition was also recorded in a short film.

https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-royal-demolition-1962-online

In 1986, enquiries were made about blowing up one of Scatter Rock's concrete hoppers at Christow. The Royal Engineers advised that they had no explosives and the Royal Marines Warrant Officer who came to look at it said that the structure was much too close to properties.

Thirteen of the 21 masonry bridges remain between Exeter and Heathfield. It had been 22 until Greenwall Lane Bridge was destroyed in 2013. Happily, Christow Station Bridge was lovingly repaired in 2022.

Behind-the-Scenes of the E&TVR

In late September, the E. & T.V.R. was delighted to receive Joseph Rogers (Railfan-Joe) and guest, the legendary Danny Scroggins, at Christow for a tour of inspection.

Joe was kind enough afterwards to pen this report for "We Are Railfans."

https://www.wearerailfans.com/c/article/exeter-teign-valley-railway

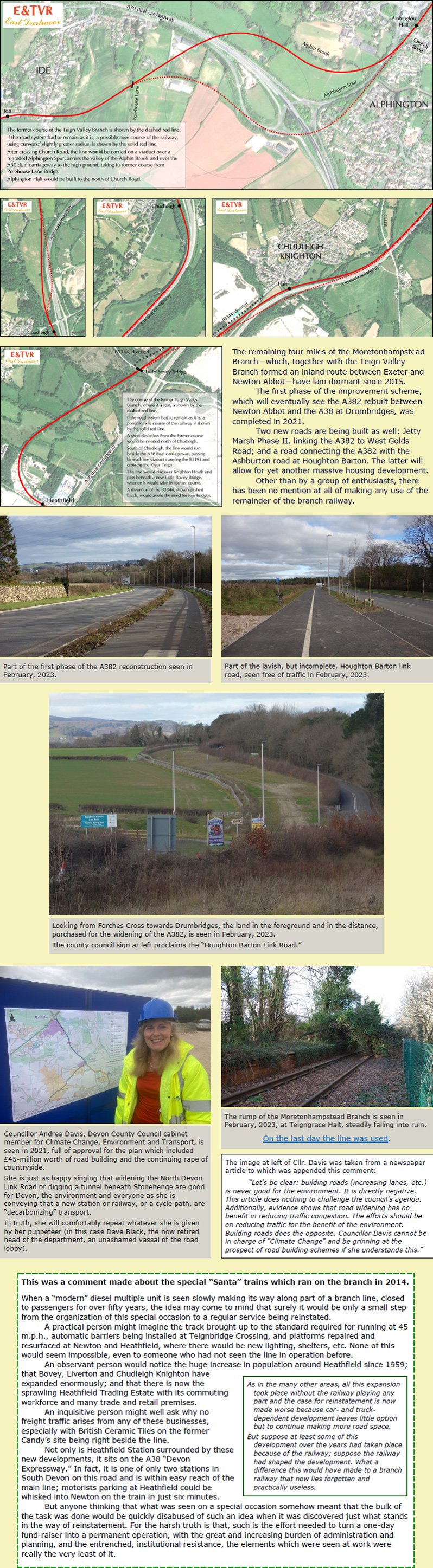

It can't or it won't be done?

Overcoming the incursions

It is often claimed that the obstruction of the Teign Valley line in two places by major road building in the 1970s is insurmountable.

Some quick doodling shows that the obstacles could be avoided, if the will existed.

It is not going to happen because government has plumped for electrifying the road system and like-for-like replacement of vehicles, in preference to redeveloping widespread public transport.

After the Dawlish Debacle, consultants estimated that the civil engineering involved in reinstating the Teign Valley could have been done for £180-million. Roughly £30-million of that was getting round the A30 incursion; £30-million was for the structural relining of Perridge Tunnel; and £30-million was for a new formation alongside the Chudleigh Bypass.

Although the overall figure would now have to be revised, the latter amount is comparable to the £33-million being spent widening the A382 between Newton Abbot and Heathfield.

Llangennech and Carmont

A closer look at two recent mishaps

From time to time, staff at Christow read railway accident reports, either in brief or in detail, as these not only cover actual circumstances and events, they also provide a useful portrayal of modern developments and practices, and reveal much about the state of the system.

Those mishaps that result from simple human error, or design or procedural failure, are the easiest to read, as the report can often only recommend tighter observance of existing rules, or minor changes to equipment or systems.

Some, though, expose huge and fundamental shortcomings or weaknesses which have crept in over the years or have come about as a result of a shrinking and less purposeful railway.

Two recent reports have excited the General Office; one because it brought home how unseen trains can be and the second because of lost versatility.

The approach here differs markedly from that of the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, in that more questions can be asked and more background detail can be dwelt upon, which would be outside the scope of investigators.

They must forensically establish what led to the derailments but in so doing it seems that they overlook the small, human interventions that could have been made. Perhaps the branch chooses not to look too closely here for it may lead towards laying blame, which is not the purpose of the investigations.

Hindsight has not been used to conjure up flukes: the trains may have been saved by ordinary actions which were quite possible.

Brief correspondence with R.A.I.B.

September, 2023: Network Rail Infrastructure Limited pled guilty to a contravention of Sections 3(1) and 33(1)(a) of the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 at the High Court in Aberdeen.

The track authority admitted that it failed to ensure, so far as was reasonably practical, that railway workers not in its employment and members of the public travelling by train were not exposed to the "risk of serious injury and death from train derailment" as a result of failures in the construction, inspection and maintenance of drainage assets and in adverse and extreme weather planning.

On 8th September, Network Rail was fined £6.7-million, the highest financial penalty ever to have been levied on the state-owned body for health and safety failings. Judge Lord Matthews said the fine had been reduced from £10m because Network Rail had admitted culpability on the first occasion the case was called in court; it had taken actions immediately following the crash to improve health and safety standards, and was a publicly-owned body.

Weeks earlier, £14-million in fines had been handed down in the case of the Croydon tram crash.

Position Closed

Rumours that plans were afoot to close all booking offices sparked protests in August, 2022.

Just after eight in the morning on 23rd August, the scout joined the protest at the front of St. David's Station and greeted the six-or-so already there. No active staff took part and it was a pretty poor show for a union initiative with the backing of several other interdenominational organizations.

Dee from The Bookery walked up. The scout asked her if she had caught the train from Crediton and she looked sheepish. A message later explained why she had had to drive to St. David's.

It wasn't long before a First manager appeared and asked everyone to move to Bonhay Road, declaring that it was a union protest and therefore could not take place on railway property.

The scout had a go at him: "Hainsey, Tubby Hopwood, Bare-Arsed Shapps, Councillor Ginge and assorted "celebrities" were there to reopen Okehampton but on the first working day not a helpful face was to be seen as some intending passengers wandered around in a daze, being unfamiliar with rail travel. The problem with the industry is that it has a bloated and duplicated management and a support industry which is like a huge limpet."

This was received with the same blank look that people say they get when it is pointed out that the offering at a fast-food establishment, when it comes, is much smaller than the illustration on the menu had suggested. The rail manager, who looked like he enjoyed fast food, strutted about with a walkie-talkie to his ear, as if to emphasize that he was only following orders from his superiors.

The scout made to go but one militant said that he intended to stay. Manager man, who claimed to understand the protestors' purpose, said he would have to get the police and ten minutes later two constables emerged from the Post Office entrance.

Before they could speak, the scout came out with: "You know they'll be coming for you after the booking offices have gone, don't you?" When the lead officer spoke, the scout diverted from the issue: "Is that a faint Irish accent I detect?"

"More than faint, I hope," he replied.

"Southern Irish, I would say. Do tell me the county. No, let me guess."

Eventually, he got a word in and asked the protesters to move beyond railway property. As he was being decent, the scout thought it best to go; the others followed. The P.C. came as well and opposite the Windsor (the former hộtel) he answered the question: "Limerick." If the scout had been clever, he would have come up with a verse appropriate to the occasion. The constable, suddenly becoming human, said that he was concerned about losing guards on trains and was sympathetic towards the protest. He had been with Surrey Police and wanted to transfer to Devon & Cornwall but the interview was delayed and he joined the Transport Police instead, which involved a short conversion course.

Passengers taking leaflets were mostly pleasant and open. The harsh reality is that many of them would have bought their tickets elsewhere. The challenge for operators bent on relentless cost-cutting of passenger-facing staff is to provide for the diminishing number of passengers who still choose to go to a booking office window to buy a paper ticket or to enquire about train services. Others may need assistance occasionally, such as when their portable telescreens have gone on the blink.

After a while in the less advantageous position away from the station frontage, the group walked to Central Station. A lady introduced herself as Rebecca. She looked very young but told the scout that she was forty. She had been involved with all sorts of activities and was very politicized. Holding a doctorate, she ran a course at the university; the subject went mostly over the scout's head until she mentioned the 19th Century "Rebecca" protests against turnpike tolls.

The two coppers drove to Central, perhaps to check that the group had not strayed beneath the canopy; the scout had promised that it wouldn't so that the law lads could have their breakfasts undisturbed.

After the others dispersed, the scout continued talking to Rebecca for what must have been nearly an hour. She had said that she was off on holiday to Majorca and the scout had asked her if she had heard of the Flight Free campaign. She said that she would have very much preferred to travel overland and the scout advised that there were agencies who would help, or even who specialized in such journeys. She did not drive; her partner, working in the coffee shop there on the Crescent, could drive, but did not. Even after the scout had shaken her hand and said "cheerio," the conversation continued.

Of course, he had to point up at the place where "SOUTHERN RAILWAY" once stood out from the stonework and to the valance where principal destinations were displayed on the green glass: "BOURNEMOUTH," "BRIGHTON," "BUDE." Actually, Bude may not have been there. "You can have no idea what once went on here," the scout said.

Earlier, the scout had thought he would catch the 0919 to Barum, but when he got away it was gone ten. He could have caught the next one from Central but shot down the hill. He went to buy a "priv" return from the window to show support but, laughably, there was a queue. So he handed leaflets to those waiting and scarpered, lest manager man reappear and shout: "Oi, I thought I told you ... !"

The scout bought his ticket on the train, after telling the guard what he had been doing. They chatted further at Eggesford, when the scout asked for the train to be stopped at Umberleigh. The guard, who had recently graduated from the gateline, estimated that about 70% of passengers bought their tickets beforehand.

Later, after visiting the Cobbaton Combat Collection and climbing Codden Hill, the scout had a chat with the ex-Civil Service booking clerk at Barnstaple, who had been on his own because of sickness. The scout gave him a leaflet and discussed the issue with him. He told the scout that a manager had come to Barnstaple the other day but the clerk had been too busy to give his boss any attention.

Vague ideas about a new, flexible role for displaced booking clerks circulated in 2022, one of the causes of the labour dispute. As High Street shoppers have resorted to the worldwide web, so have passengers: as many as 90% have now bought their tickets before they get to the station. The one member of staff on duty at small stations has long been versatile, only spending part of his turn behind the window. When the scout chatted to the clerk at Yeovil Junction first thing on a summer's morning, the friendly and conscientious fellow was litter-picking in the car park. The man at Barnstaple had been tidying the station and was about to lock the toilets.

Versatility has long been a notable attribute of Teign Valley staff, each member of which is qualified to do at least four jobs.

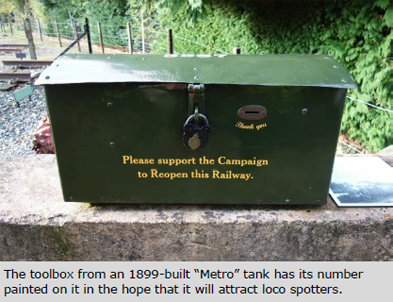

The Alamy

Staff at Christow is used to seeing men come to take photographs or numbers in pursuit of their peculiar pastime. Sometimes they will approach and engage in brief conversation, but usually only to ask where a particular vehicle in their spotter's book may be found. Others will try to avoid contact. Some do "drive-byes" on the lane overlooking the yard, perhaps thinking that it is a public road. They may claim that they have happened upon the place and, in snapping away from the doors of their cars, they are doing no more than curious passers-by would do. In fact, it is a private road that leads no further than the gate of a retreat.

The funniest are the men who bring their wives and after having had the greatest difficulty in cajoling their agreement to the visit in the first place, then have to promise them that they will not dwell for long. The frumpy wives nearly always sit in the cars looking glum, without so much as winding down the windows or getting out to stretch their legs. The river, a draw for most, would probably hold no appeal even if it were pointed out to them that they may catch sight of otter or kingfisher. Staff likes to pounce on these fellows and hold them up while they are out of sight of their dearests, for this soon causes their walkie-talkies to ring. "It's her; she wants to go shopping," they say, as they feel the marital chain pull tight.

A few—sadly, a very few—are interested in more than just taking numbers and will happily talk like normal men on a range of subjects, or at least discourse in depth on their special interest.

Most of the pastimers are too mean to put a farthing in the contributions box; they must tell themselves that nothing has been bought and no benefit has been received; therefore no obligation is felt.

But, they have deliberately sought out the project and it must therefore be a part of their interest. The fact that the things they follow have been saved from being broken up, or have been expensively repaired, and lie in an appropriate setting for enthusiasts to see is a kind of offering which ought to be valued.

By all accounts, this fraternity is generally mean. The pickled railways complain about those who just want to observe or take photographs but who refrain from paying fares or buying a book in the shop or a sandwich in the caff. This type will not consider it a duty to help support the provision of the entertainment, whether it is seen as moving spectacle or in a static form. Similarly, a great many now expect to enjoy music, films and other artistic or intellectual property without making any contribution towards its creation.

Thankfully, at Christow, a small number of visitors are generous—some exceedingly so—which makes up for the natural spongers. It is human nature for some to see no gate or restriction or admission charge as a gift and for others to feel trusted to do what is right.

The discovery on the photographic library, Alamy, of a batch of shots taken at Christow has revealed another category: those who are not content to visit the project and point their cameras, but intend also to offer their work for sale.

The photographer, Andrew Payne, who seems from his choice of subjects to be a local fellow, has done nothing wrong. He took his pictures from, or close to, the public footpath which crosses the railway and there is no law, and little etiquette, governing what can be done with a camera at a public place, more is the pity.

But the work at Christow has involved an enormous expenditure of time and effort over many years. Wresting the railway back from nature, clearing the ground, laying the tracks, bringing in vehicles, putting up buildings and furnishing the place has cost the men responsible for it dear, but has brought them little in return.

Those who take photographs for their own enjoyment or for sharing, though they may not think of contributing even the token amount that most visitors would put in the collection box of an empty church, can be ignored. However, someone who photographs the work, in small part for his own enjoyment, but also with the thought of gain, rather annoys staff at Christow.

Photographers do not post their work on Alamy for the pleasure of others; they do so in the hope of enrichment, though it is doubted that many shutter-clicky amateurs make much money this way.

The railway's photographer has replicated most of the pictures that Payne took and posted them on Flickr, where they are available for use by anyone for non-commercial purposes under a standard free-use licence.

The railway's Flickr gallery:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/196523413@N04/with/52363026833/

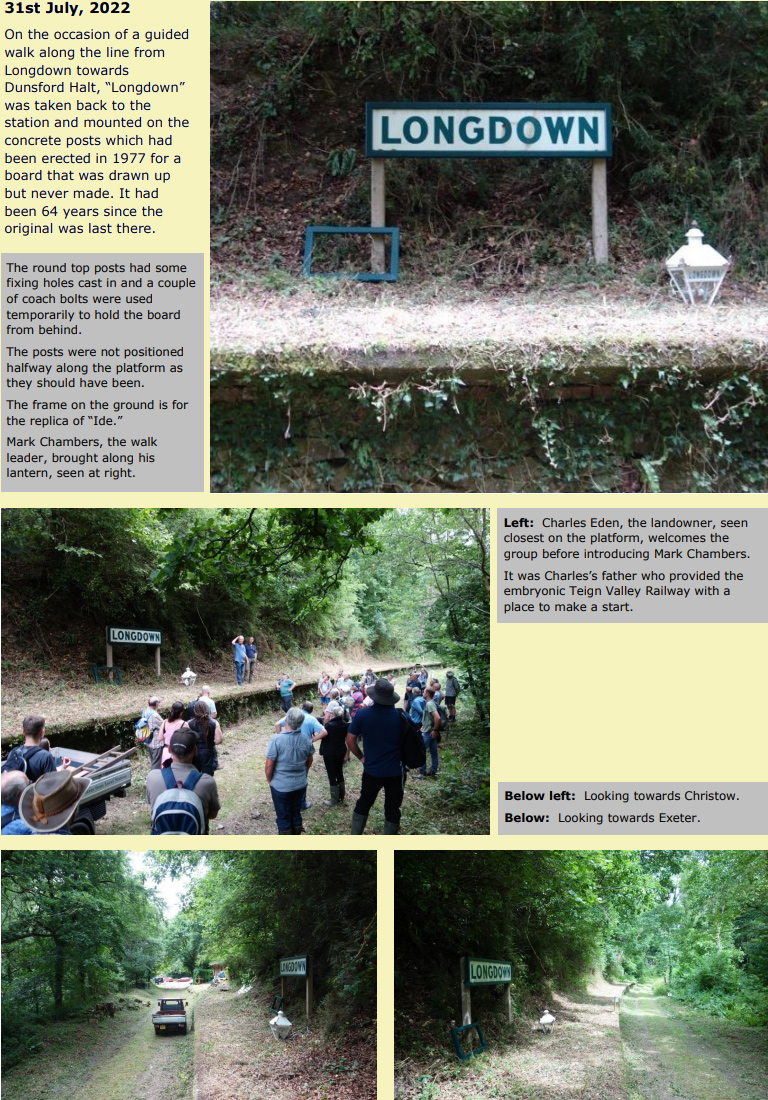

One Running-In Board Goes All the Way Home

The story of how two of the Exeter Railway's original running-in boards were returned to the Teign Valley is told in Signs Come Home.

But "LONGDOWN" was still 3¼ miles from its former station and so, after it had been given a new wooden frame, an opportunity was awaited to put it on display up the line for some people to see.

On 31st July, 2022, a guided walk was arranged by the landowner, Charles Eden, and Mark Chambers, the well known Teign Valley Branch enthusiast and historian. It was agreed that the board could be put on the concrete posts, installed in 1977, for the occasion. It had last been not quite in the same place 64 years before.

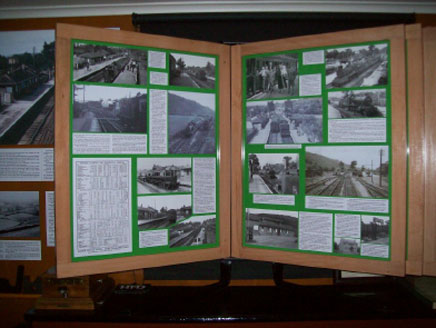

Teign Valley History Centre

"Preserving our common cultural and historical heritage."

Or "Staring through one-way glass at the poor and primitive."

It could be said that when a society has lost sight of what it is doing and where it is going, when it has no delight or satisfaction in the present and no real hopes for the future, it turns to look backwards, perhaps naively believing that times past were better, happier, more stable and less complicated.

Or it could be that the newfound tendency to retrospection comes from a sense of superiority, stemming primarily from technological advancement. People peering and peeping through a window into the past are curious to see how the ancients managed without the electronic wizardry that governs every thought and action today. How was life bearable, or even possible, without electricity, hot running water, cars and all the trappings now taken for granted? Although, listening to some, having an inadequate broadband signal is equal in hardship to having to use an earth closet at the end of the garden.

Either way, it is observation done from a safe distance, with detachment or aloofness, like historical voyeurism, and no attempt is made to connect even with people who only recently occupied the same homes and trod the same paths.

For some men the attraction is obvious and well understood. Like controlling a model railway or arranging tin soldiers, history or heritage or re-enactment provides an escape, one that is safe and settled; there is no danger or dynamic—no cold or wet, no scold or threat—and nothing is unfolding, yet to be decided. And there are unchanging facts and figures that can be sought out, learnt and repeated to prove mastery of the subject.

This thirst by the amateur for knowledge—if not understanding—of what went before is widespread. In villages which have become virtual museums, where it is hard to see any history being made, there will be the history group, whose greying members may live in houses whose names are prefixed "The Old." The Teign Valley scout has ridden through countless villages with an old forge, vicarage, chapel, bakery, station or internet café and been struck, on sunny summer's days, by how utterly lifeless the places seem.

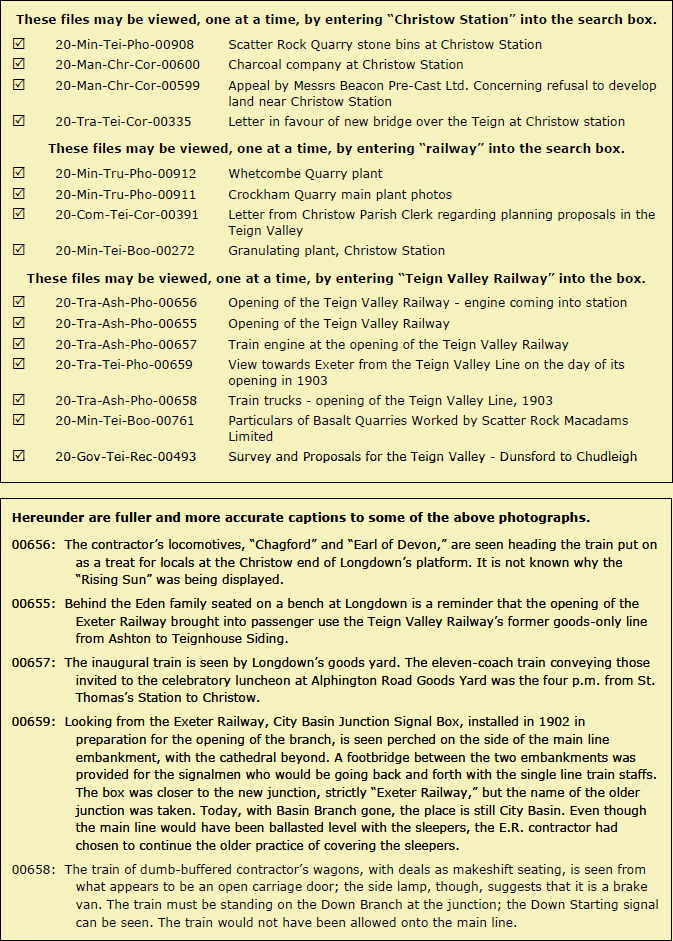

Despite this carping, it has to be admitted that were it not for the efforts of one such history group, the digitized archive available on the Teign Valley History Centre's pages, parts of which anyone with an interest in the branch railway should find absorbing, would still be hidden away from view.

Here, at least, dusty documents will be given some meaning and life.

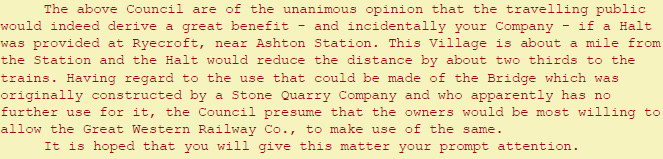

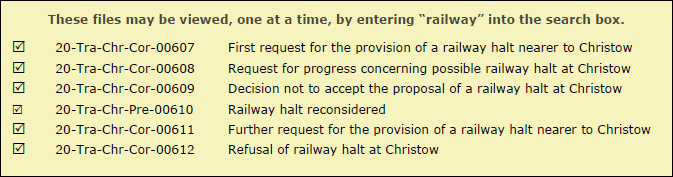

Christow Village Halt

Several files contain correspondence on the subject of a proposed halt which Christow Parish Council pressed for three times between 1936 and 1948, asserting that such an addition would more conveniently serve the village.

On 1st February, 1936, the council wrote to the G.W.R. Divisional Superintendent, R.W. Higgins, Esq., at St. David's Station.

After some exchanges, the council's request was finally answered by the Divisional Superintendent on 3rd. July, 1936.

The council tried again in 1946, this time addressing its letter of 27th November to the Christow Station Master, Mr. Tucker, who promptly acknowledged it and forwarded same to the Divisional Superintendent, by now H.A.G. Worth, Esq.

The matter was summarily decided by the Superintendent, using much the same wording as had his predecessor, on 5th December, 1946.

There is no copy of the parish council's plea of 27th February, 1948, to the Divisional Superintendent, whose old company had been taken over the state just two months earlier, but there is this reply.

Such was the infancy of the organization that letterheads had not yet been printed. Staff often continued to use Great Western stationery but perhaps this officer was a socialist who approved of nationalization.

Ten years later, the passenger train service was withdrawn.

https://www.tvhistorycentre.org/search.php

Why the rejection?

It may seem like the officers of the Great Western and its successor, the Railway Executive, were being intransigent and were mindless of the needs of the district, but this was not really the case.

Christow and Ashton stations lay 1⅝ miles apart. Christow served Bridford, Doddiscombsleigh and the upper valley as well as its own village. It was the central crossing station and still forwarded substantial mineral traffic. Ashton, the former terminus of the Teign Valley Railway, had few passengers but coal was still received and staff was needed for the level crossing.

The proposed halt south of Christow River Bridge would have been roughly half-way between Christow and Ashton stations and less than half a mile from the church in Christow.

But Christow is a long, straggling village with no defined centre. Though the church was closer to Ashton Station than Christow, being ⅞-mile and 1½ miles distant respectively, the junction of Wet Lane and Dry Lane at the other end of the village was only a mile from Christow Station.

The halt later proposed for Ryecroft, the same distance from the church as the other suggested site, would have been less than half a mile from Ashton Station and would have entailed the railway taking responsibility for the quarry company's river bridge or obtaining permission to use it.

The officers' decisions took all this into account, as well as the small number of passengers likely to be attracted. Even if a halt had been built in 1936, many of its passengers would have been taken by the competing bus service introduced in 1947. The 1948 response also had this to consider.

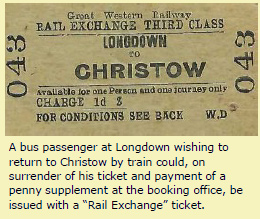

Even then, road-rail interchange was possible, co-operation or co-ordination which is still to be fully rediscovered.

It is best not to make even an electrified railway like a tramway, with close and frequent stops, but to develop isolated stations and halts where possible into hubs from which light road vehicles radiate.

There are more files containing documents or photographs which will be of interest to railwaymen and enthusiasts, some of which are listed below.

Conicity

One of a series of films demonstrating first principles to those with an engineering bent.

The "party piece" which customarily is performed for visitors to the railway has been filmed in its full form and published on the Tube as "Conicity."

It was thought, perhaps hoped, that the novelty of this real demonstration would see it spread beyond the small circle that the Tube's system would automatically select. It was imagined that those with enquiring minds may pass it on to friends, with such comments as: "I can't quite see how this is done" or "this is intriguing."

But no such wider interest has been shown, in part perhaps because the types to whom this would ordinarily be of interest are not inclined, like effervescent youngsters would be, to share or make the small effort of clicking their approval, which it is believed would improve the ranking.

A link was posted on two local-interest Mughook pages, where it is noticed that every picture of a steam engine or diesel, no matter its relevance, captioned or not, receives a flurry of likes within minutes, while any snippet that requires a little concentration is soon overtaken and descends the column into obscurity.

When "Conicity" was met with the usual half-heartedness, the scribe was moved to comment:

"Really? Is this all I get: five likes and a handful of views for the effort involved? I had to turn three pairs of wheels, make a very tall dunce's hat (with a bit of HST piano hinge joining the two parts) and film a demonstration, unique to the Teign Valley. You will not see this done anywhere else. It is very disheartening that so many railway enthusiasts should show such indifference."

Once again, this wretched medium, with its horde of addicted, fanatical followers, showed that however tame the topic or small the interest, there will often be someone who has nothing useful or pleasant to say. "Conicity" proved to be no exception.

"Same principle as pulley profiles to stop belts from coming off. Nothing new. Its not surprising anyone shows indifference....... "

Why would a man who has not commented elsewhere and who does not understand the subject bother to make an entry? All he has done is let it be known on a public platform that he is both wrong and mean-spirited.

Fortunately, the kind comment from Hetty Prestiegne countered it.

"I for one was very impressed, the first time I had ever seen proof of a principle that had been explained to me."

Track recovery at Christow, 1959

Rather like the Grade One Clerical Officer posted in "The Cottage" at St. David's, part of whose duties was scanning local newspapers each day for mention of B.R., the junior clerk at Christow periodically does a trawl of the worldwide web using "Teign Valley Railway" as the search term.

While the 1960s' clerk became adept at completing crosswords and clipping coupons, it is thought that the junior clerk here is often distracted by some of the disgusting repositories found in the cyber cesspit.

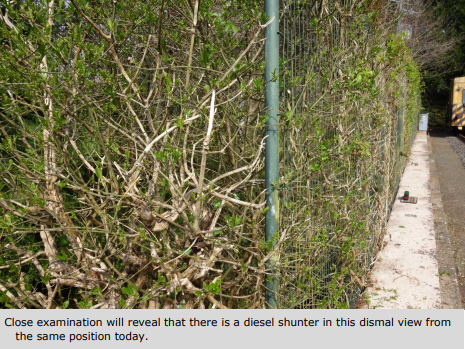

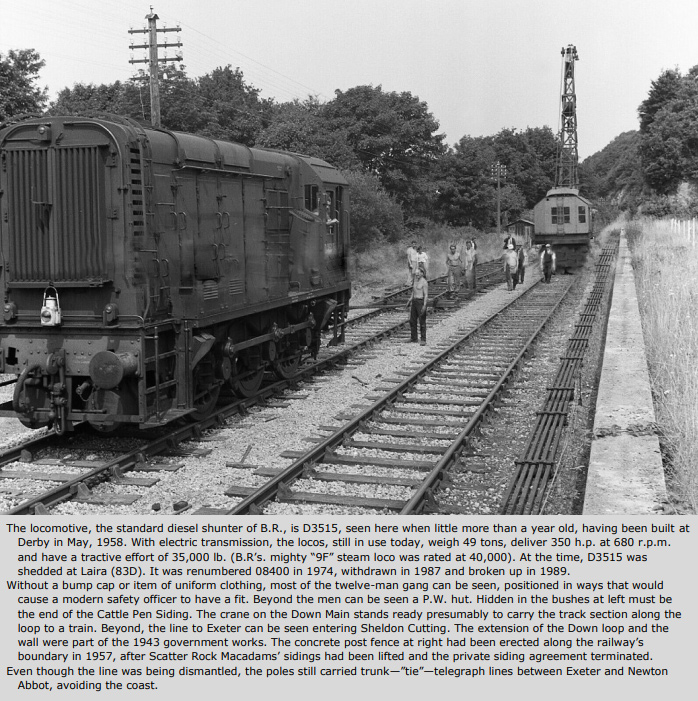

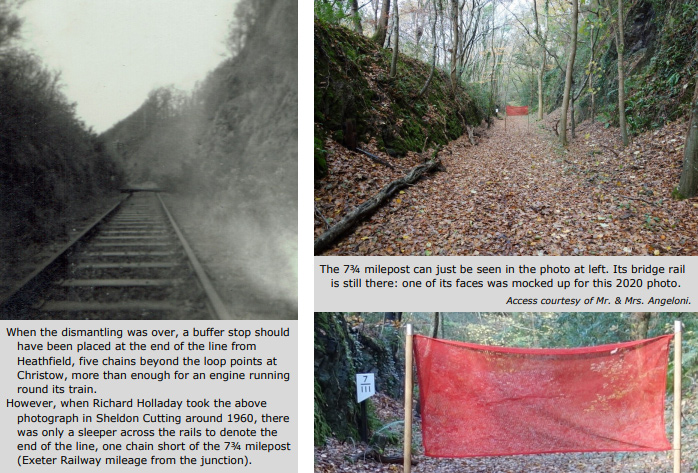

Generally, the same million search results appear but recently a new one was espied: "Track recovery at Christow, July, 1959."

When the link came up, it showed a watermarked print of a negative that had just been sold.

The position of the photographer was unusual: he was standing near the footpath steps which mark the mid-point of the branch and no other shot taken from there has ever come to light. But the most surprising revelation was the diesel shunter dragging a track section down the Up Main, which it must have done for some way along the single line beyond.

The memory of a local fellow, who would have been only three at the time, that he had seen a diesel locomotive on a demolition train at Christow, dismissed by the scribe, is thus proven accurate. The scribe had understood that the track between Christow and Alphington had been lifted in 1958.

Further testimony came when members of the Cornwall Railway Society, on their way to visit Christow, had a chance encounter on the bus from Exeter.

"A fellow passenger proved to be an ex B.R. track worker from Ide who had been involved in the demolition of the 'Teign Valley line'. He lived in a cottage adjacent to the railway and one of his neighbours was a local driver and he related to me how they used to leave the 08 shunter and wagons outside their houses each night ready to start work again the next morning."

It is, then, almost certain that the line was lifted from Church Road Bridge, Alphington, working towards Christow, where recovered materials would have been loaded away. Some of the line had only recently been relaid and this track material is thought to have gone to Cornwall.

Reference to "wagons" is unclear. One method of recovering rails is to use an engine and a wire rope to draw them up and onto a bogie wagon whose brake is hard on. Sleepers would then be picked up manually or by such as a tractor with a fore-end lift and loaded on top of the rails.

Perhaps on the approaches to Longdown and Christow, complete sections were lifted, drawn onto the remaining track and dragged as seen in the photo. Perhaps they were dragged all the way, but then the wagons would have remained on the loops, where the crane could load them.

The models chosen for display in the Temporary Booking Office are not of those locomotives that were seen day in, day out, but the ones seen rarely, and then only in the dying days of the branch.

The four millimetres to the foot scale model of a D63XX, inspired by the shot of one in B.R. blue at Chudleigh Knighton in 1968, has now been joined by a seven millimetre diesel shunter.

The reliable old locomotives can be seen at work in these film clips: first, shunting a 1,000-ton train at Westbury; and second, coasting downgrade towards Midsomer Norton on the little of the S. & D. that has been rebuilt.

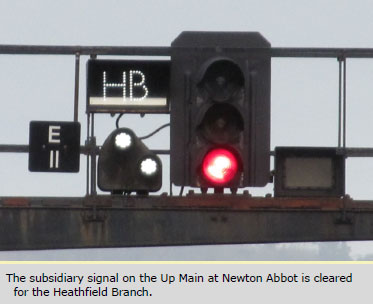

Heath Rail Link

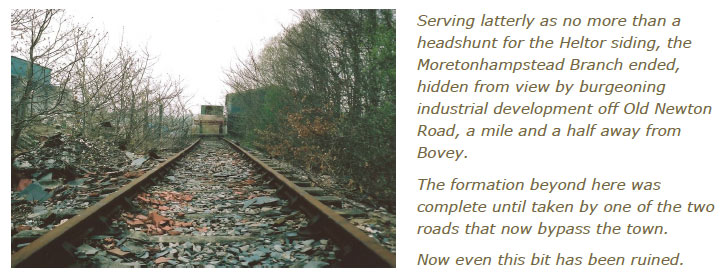

A group aiming to revive the four miles of the former Moretonhampstead Branch between Newton Abbot and Heathfield.

Just as the few words were written on the previous section at the very end of February, 2020, an announcement appeared on Heath Rail Link's chatter page.

Suddenly, backers for the scheme had come forward, stirred by government's "Restoring Your Railway" fund. Sponsored by Teignbridge M.P., Anne Marie Morris, Teignbridge District Council had hurriedly prepared a bid for cash from the "Ideas Fund" and submitted it by the deadline of 28th February.

Making a good example of "distraction politics," the "Restoring Your Railway" fund promises £500-million to "drive forward," in the words of the rail minister, "the reversal of the controversial Beeching cuts."

The "Ideas Fund" is £300,000 and bidders' delegates will be made to pitch for a share of it in two rounds of a television-style knockout contest. As a feasibility study costs around £100,000, not many bidders will be successful. Lesser sums may be granted for exploratory work, but this will hardly be worth doing in all but a few cases.

Pitiful British transport policy is seen in action; or rather rail transport policy, because road policy continues without such drama as this. The road which corresponds with the old Moreton Branch, the A382, is undergoing "improvement" between Newton Abbot and Heathfield at a cost of £30-million, not so much to ease existing traffic but to provide for future growth. The path to setting this in motion was very different and has been trodden into a rut since the 1960s.

Government, if it were truly committed to rail expansion, could have done the same as when a national cycle network was wanted: in the absence of a plan of its own, it went to the people who did have one - Sustrans. Both of the national organizations, Railfuture and Campaign for Better Transport, have long had lists of lines deserving of reopening, vainly waiting for government to switch spending from motor roads to sustainable forms of transport. But, no, it is turned into some kind of mean ritual where toffs watch the poor scrabbling for coins tossed into the market square.

It can only be hoped, against all the odds, that Teignbridge's bid is successful in some way and that the course is set to reopen a third of the branch. But there is no presumption in favour of sustainable transport. Without relaxing the rules and expediting the process, any seed corn thrown by government is likely to be devoured by corvine consultancies in a feeding frenzy, whose only contribution will be to lay the ground for further studies.

The Moretonhampstead Branch, closed to passengers in 1959, was not a casualty of Beeching but what is left of the line can be considered for a grant as much as any other. The term "Beeching" is today used to describe the whole closure programme, which in Devon, post-war, started with the Princetown Branch in 1956 and finished upon the withdrawal of the passenger service between Exeter and Okehampton in 1972.

Heathfield - Newton Abbot Community Rail Project

Appendix: Extract from Heath Rail Link's postings

Charity HST Special, 10th October, 2015

Special Trains on the Moretonhampstead Branch

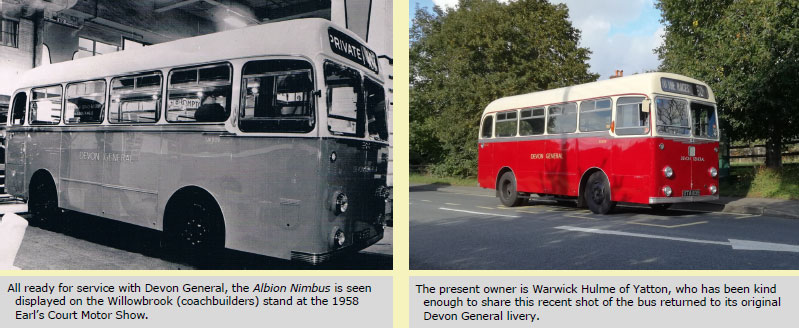

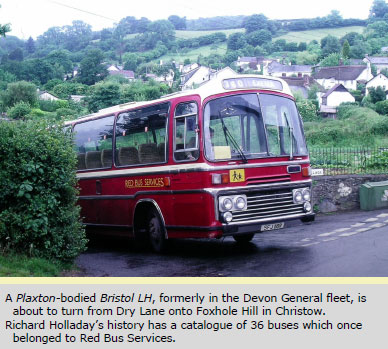

Last Run of the Albion

The end of Red Bus Services' contract

Richard Holladay provided the rare footage of a train coming off the Teign Valley Branch in Exeter, not far from where his family firm had established their works on land bought from the G.W.R. adjoining Canal Branch. His film is by far the most viewed on the railway's television channel.

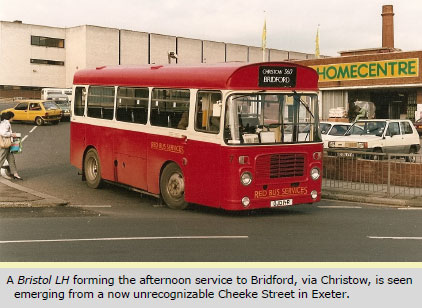

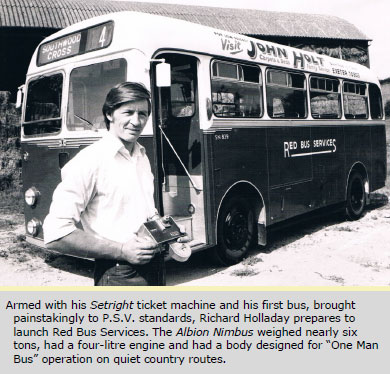

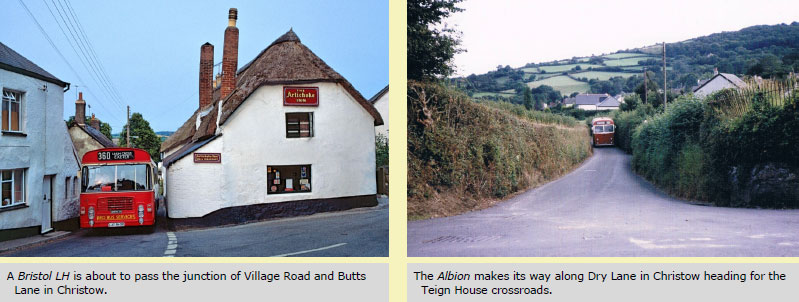

Now he has kindly made available a film which is likely to prove equally popular. "Last Run of the Albion" captures his first vehicle at points along the route of the Exeter to Christow bus service in 1991.

Mr. Holladay started his company, Red Bus Services, in 1983 with an Albion Nimbus bought from Tony Hazel (later to become Carmel Coaches) for £150 a few years earlier. It had been part of the Devon General fleet until 1971.

Red Bus was awarded the contract by Devon County Council to operate the Exeter to Christow Service 360 in 1987. This was not strictly a "Rail Replacement" service because it had competed with the trains since 1947. It quickly took most of the railway's passengers and made possible closure of the line in 1958. In the words of the public notice posted at stations: "Passenger Road Services are already in operation in the area... ."

It is believed that the film was shot on the last day of the contract, Saturday, 24th August, 1991, when the Albion was rostered instead of more modern vehicles in the Red Bus fleet.

At this time, Devon Bus 360's ten Monday to Saturday through services covered the roads via Longdown and Dunchideock in both directions.

Lest any Teign Valley resident try to put names to the passengers in the opening scene, it must be stated that they were "extras" not there on the day; the sequence merely adds life to the film.

Mr. Holladay's Red Bus empire came to an end in 1997 but a thoughtful fellow could not let it go unrecorded for posterity. As well as writing the history of his family's firm, in which he played no part, he has penned "A History of Red Bus Services (East Devon)," a fascinating account of the mechanics, bureaucracy and day-to-day trials of running a local bus company. A copy is held at Christow Station and others may be obtained from Mr. Holladay by writing to the address below.

The Albion remains on the road, so it may be possible to re-enact this service for another film.

The Western in Western National

Between the wars, the Big Four railways acquired substantial interests in bus companies but tended to let them develop without much co-ordination between modes.

Western National was a joint venture by the Great Western Railway and the National Omnibus & Transport Company. Locally, the G.W. also had shares in Devon General.

If the period is thought of as having had good public transport, this is more because it was abundant; such co-operation as there was probably came only from parochial interest.

Deregulation aside, modern public transport has been refined in many metropolitan areas, although all bus services have to suffer congestion caused by the weight of self-centred transport.

In a turnaround of ownership, many passenger services on the disintegrated railway network are now run by bus companies under contract.

Rural bus services have been reduced or withdrawn over the years and the kind of network envisaged by this railway still figures only in the policy of the political party most concerned with the environment.

In the district of East Dartmoor, this would see the two branch railways forming the backbone, with compact buses—descendants of the Albion—mostly radiating from stations, gathering and dispersing train passengers as well as connecting the outlying settlements.

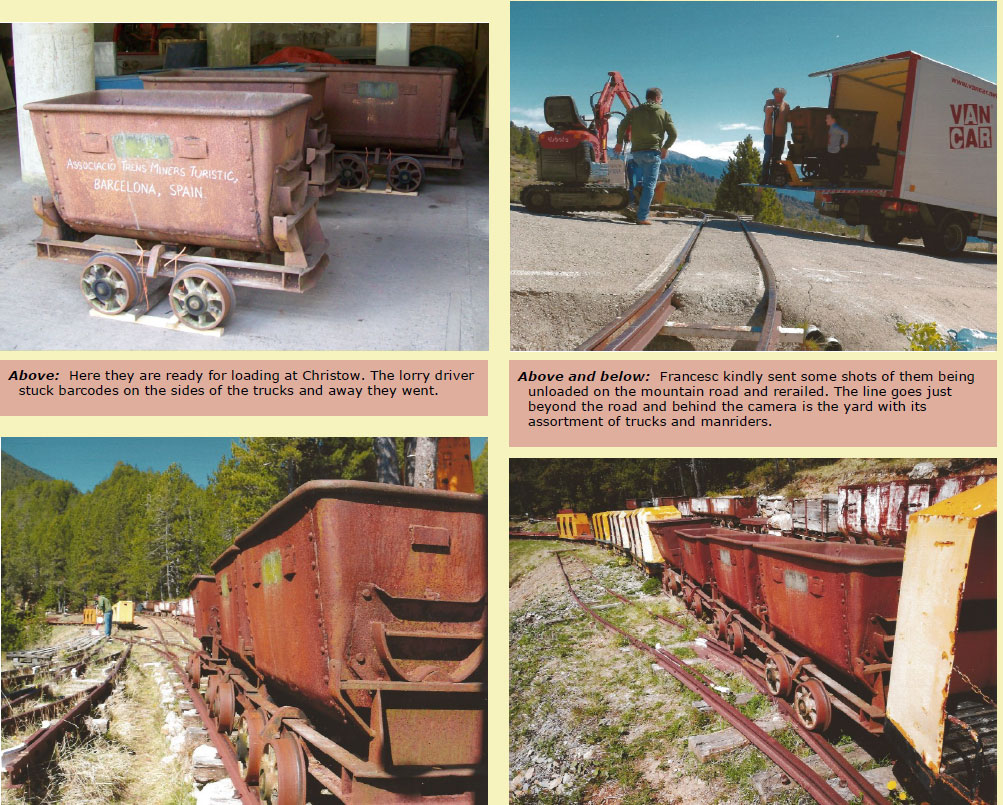

Mountain Mine

Underground side-tipping wagons sold to mining enthusiasts in Catalonia.

Never taken into stock after their recovery from the Watts, Blake, Bearne & Co. clay mines in the Bovey Basin, these trucks had only been used for stillage at Christow and it was rather hoped that they would one day have gone to Western United Mines at Pool (South Crofty).

The trucks are colloquially referred to as “UVs” and are intended for shafts and tunnels. The rim of the tub is less than an inch outside the wheels, which are independent and have tapered-roller bearings. These trucks have coupling pins but no buffer plate, as they were always rope-hauled.

Finally despairing of them ever going purposefully underground again, the three with original riveted Hudson bodies were advertised for sale.

There was some interest from home enthusiasts, but the best offer came surprisingly from Spain.

On 8th April, 2019, they were sent to Francesc of Associació Trens Miners Turistics (which it is thought translates as Tourist Mining Train Association). Snow prevented them reaching their new home at an old mine high in the mountains until May.

The trucks were sold as two-foot gauge but Francesc was advised that they would run happily on 600mm. (1ft. 11⅝in.).

No instructions were received prior to collection. It was thought unnecessary to put the trucks on pallets and instead laths were placed simply to keep the flanges off the ground and to stop the trucks rolling. These are still in place in the mountain road picture below.

These trucks last carried ball clay (whose residue can still be seen) from mines in the Bovey Basin.

Reaching the deposits from the surface put an end to underground mining in around 1998. Few ever knew that there were mines, even though the main road passed close to the adits. I was privileged in being taken down one of them in the late 1980s and I saw trucks like these (or maybe these very trucks) being loaded at a working face, four at a time, each with 12 cwt. Output was fifty tons a shift; on the surface the buckets were scooping up five tons at a time, but the better quality clays were not always available and there were seams of lignite (brown coal).

When I visited the clay museum at Norden (Isle of Purbeck clay came from Devon, there being no granite in Dorset), I told the lady on the gate how familiar I was with what I had seen. She asked if I was from Cornwall. It’s funny how Devon mining gets overlooked.

C.B.

https://www.facebook.com/trensminers/

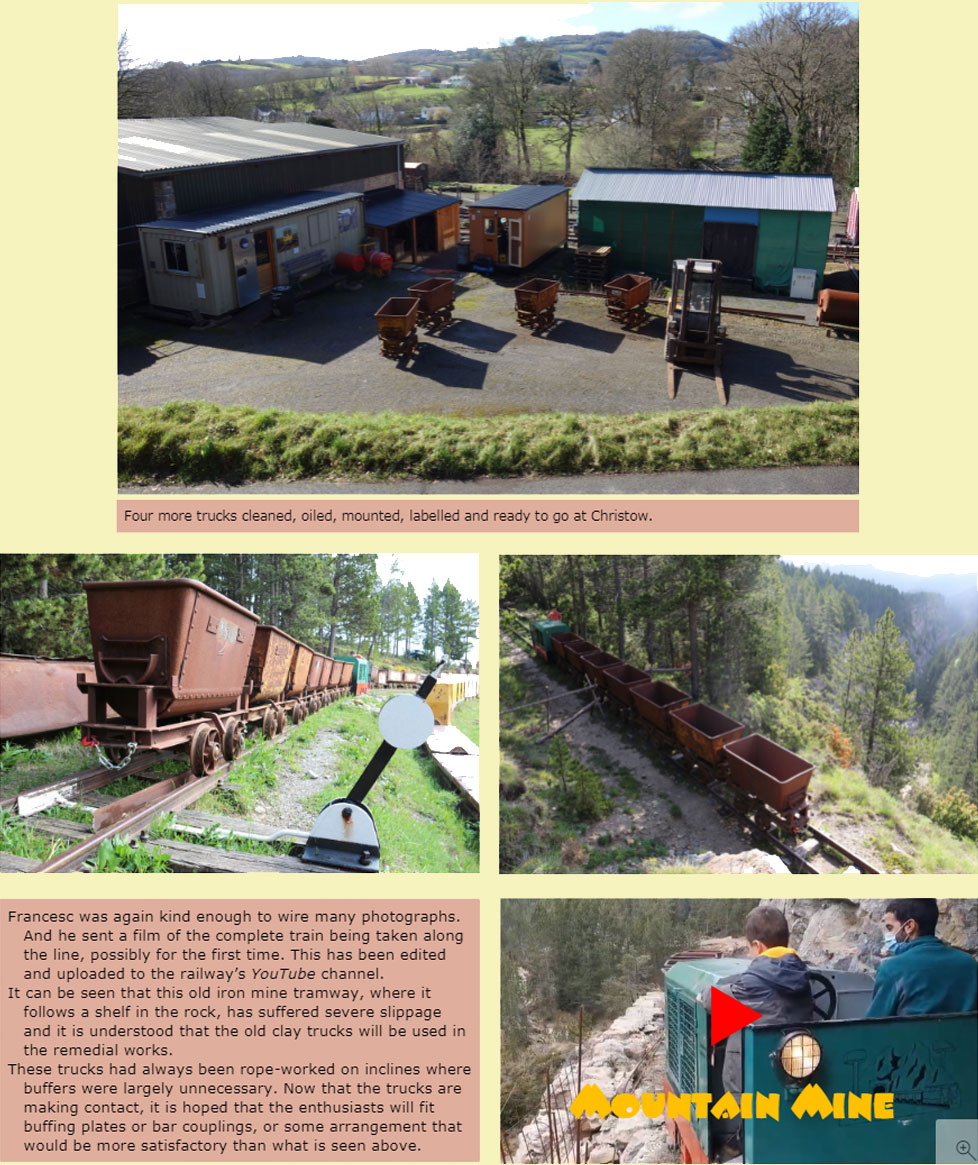

January, 2021

It was decided in 2020 to sell a further four trucks. When the worst of the plague had passed, they were offered to Francesc in Catalonia, who quickly agreed to take them.

Shipping was more complicated, Great Britain having by this time left the European fold. It was necessary to obtain an E.O.R.I. (Economic Operator’s Registration and Identification) number, which was remarkably straightforward.

The trucks were collected on 23rd February and after some customs delay at the other end, they joined the other three on the mountain line.

Francesc requested a little history of the ball clay industry that employed his trucks and this was prepared and translated into Catalan.

The Permanent Way (and the Truth and the Life?)