Production

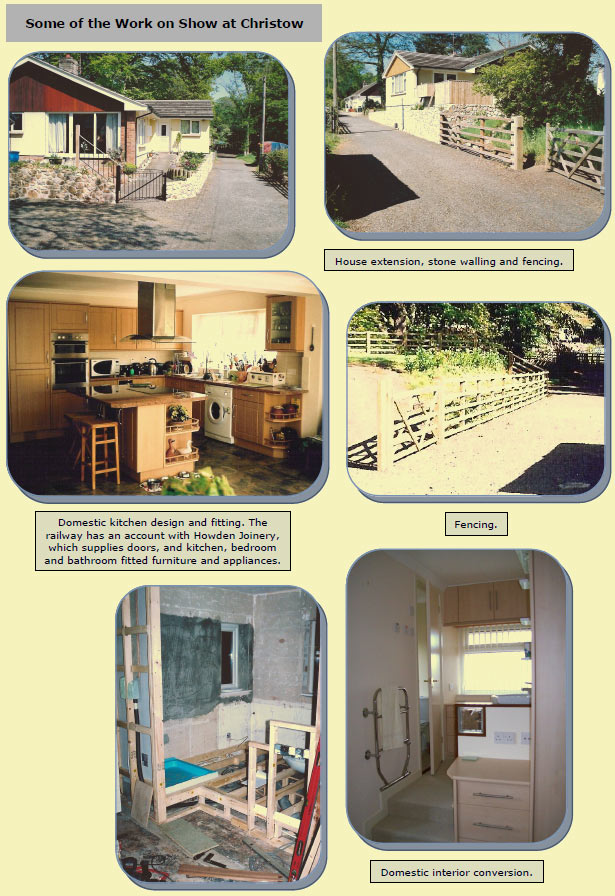

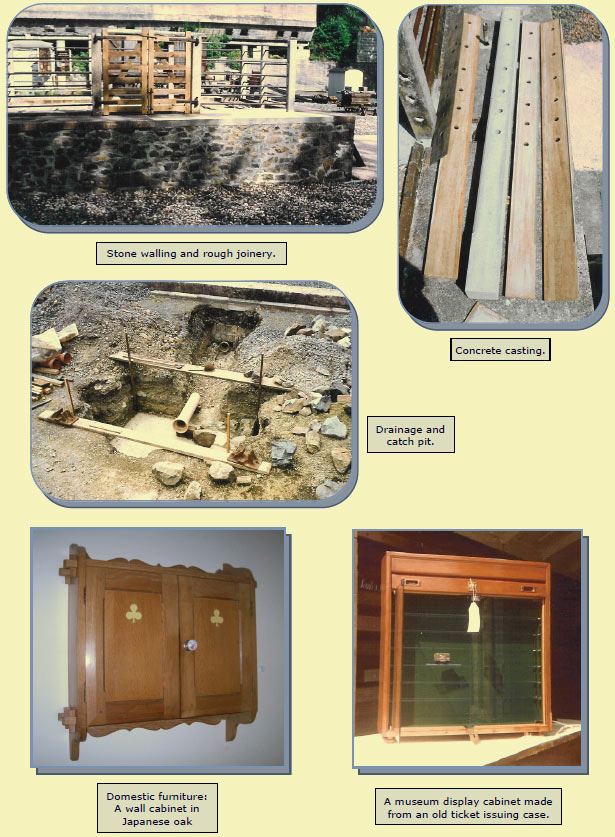

Work of many kinds is produced from the Building Department yard at Christow, the smallest and only part of the station trading estate so far to have been acquired by the railway.

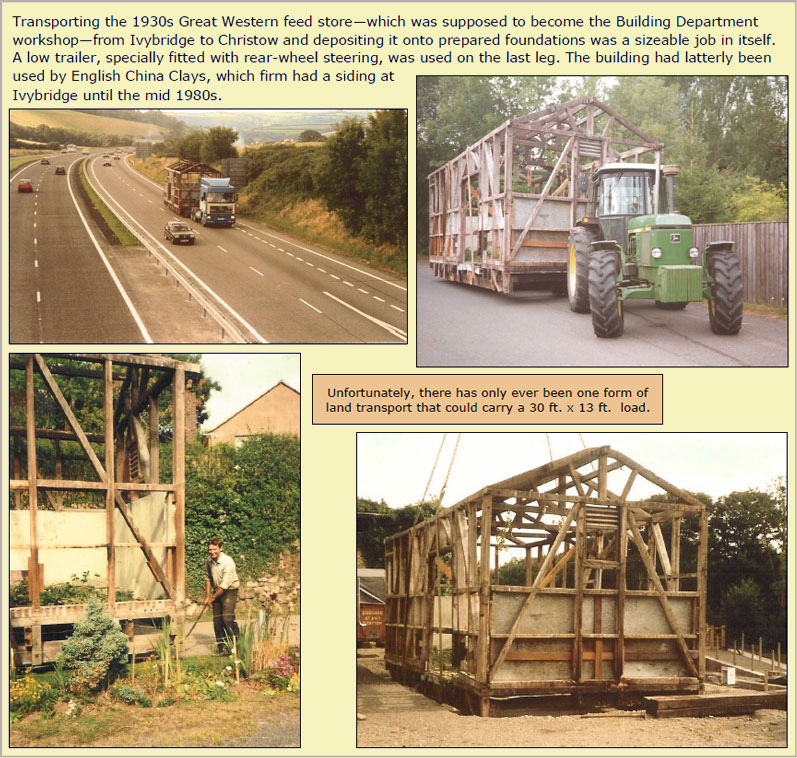

The main workshop building, the shell of a 1930s Great Western feed store brought in one piece from Ivybridge in 1993, is used to work on larger projects, while what should be the site office, a converted insulated 20 ft. container, provides a temporary, warm and secure workshop for the smaller jobs.

The site office is entirely adequate for a lot of work. Machines and furniture can be moved around on their wheels to make whatever space is needed. The Felder combination woodworking machine, weighing a ton, can be manoeuvred to suit different functions and workpieces.

Nevertheless, it will be a great benefit to the railway when the main building can be fixed up properly in G.W. style, with its sliding doors leading onto the platform on Scatter Rock No. 2 siding.

The E. & T.V.R. claims to have a wider range of abilities and a greater breadth of knowledge, relative to the size of its staff, than any other railway in the country. And, judging by the standard of some of the work turned out of bigger places with far better facilities, ample size and resources are no guarantee of quality.

The railway specializes in the classes of work that it needs to do for itself. This capacity is available also to other railway operators and those in the hobby railways who are discerning enough to realize that the expertise they want cannot be obtained cheaply.

Other more general work is also taken in, for which the railway is well equipped. Undemanding work is, however, best given to jobbing tradesmen, for the railway is unlikely to be able to price competitively in this field.

The station is something of a shop window. It is hoped, though, that "shoppers" will be able to differentiate between the work done and that yet to be done.

Along with the usual mix of small works and the endless round of maintenance jobs, the railway has the following projects in hand:-

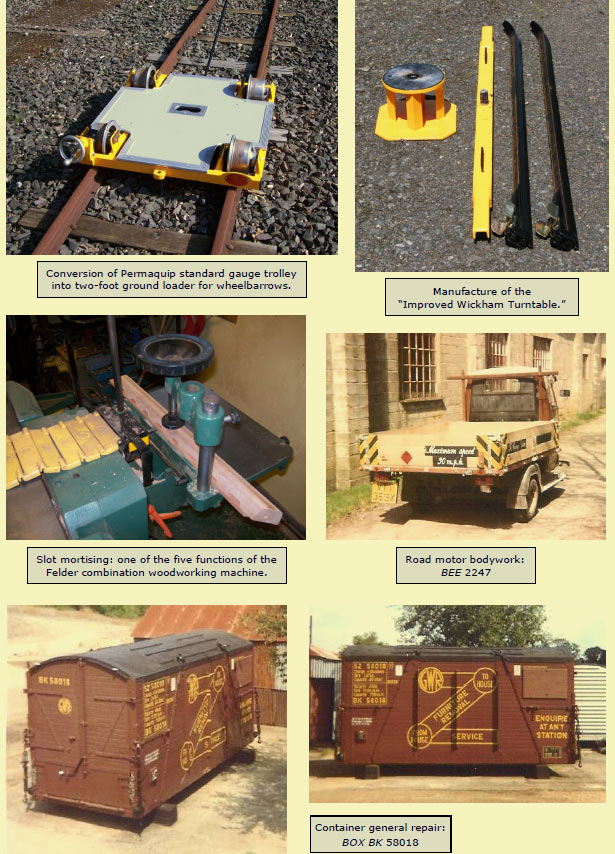

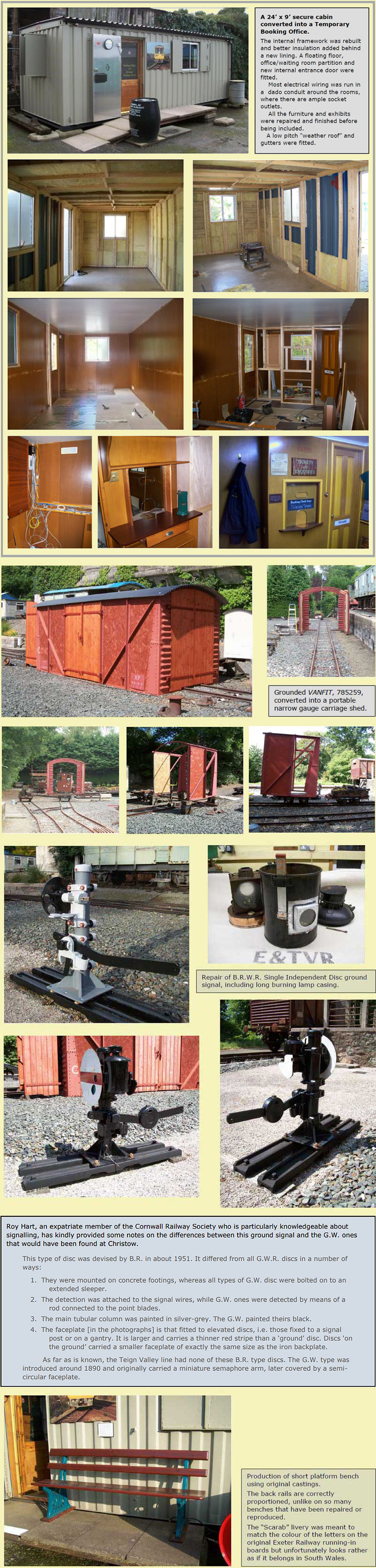

Repair and alteration of "boiler end" of loco, D2269.>> Work in progress >>

Overhaul of Minks 78642 & 78651.>> Work in progress >>

Overhaul of FERRYVAN 889027.>> Work in progress >>

“ “ “ “ PYTHON 9437>> Work in progress >>

“ “ “ “ TOAD 35410>> Work in progress >>

The following have been recently outshopped:-

BEE 2309 — commissioning of new autotruck.

GANGCAR 194 — rebuilding of motor trolley and trailer.

Four Permaquip trolleys ― general repair and conversion.

Secure site cabin fitted out as a temporary booking office, complete with repaired furniture.

G.W.R. platform bench.

B.R.W.R. Single Independent Disc ground signal.

Platform trolley.

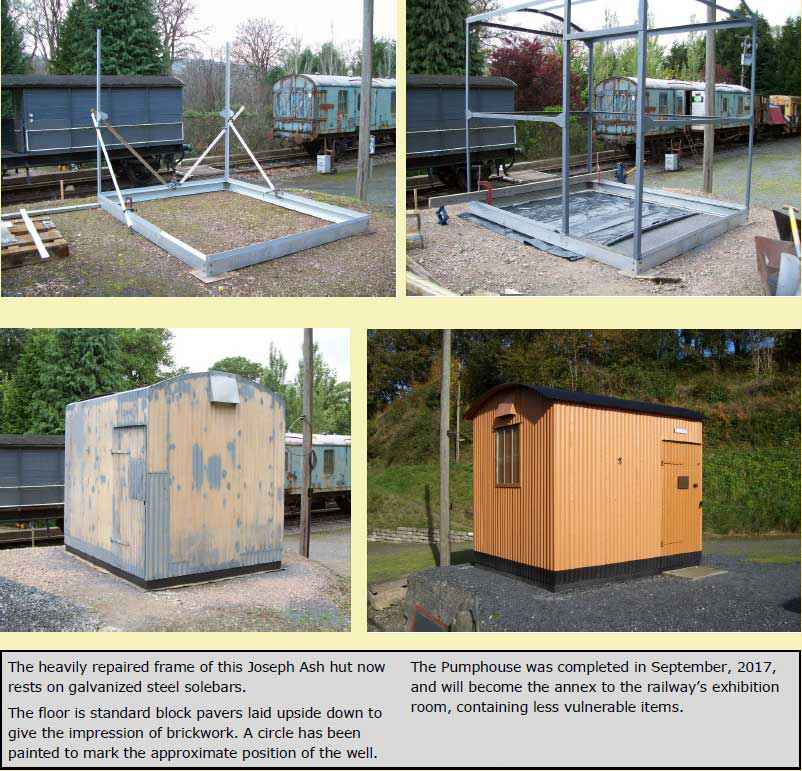

Repair and re-erection of the Christow pumphouse for use as an exhibition annex.

Construction of motor trolley shed.>> Motor Trolley Shed >>

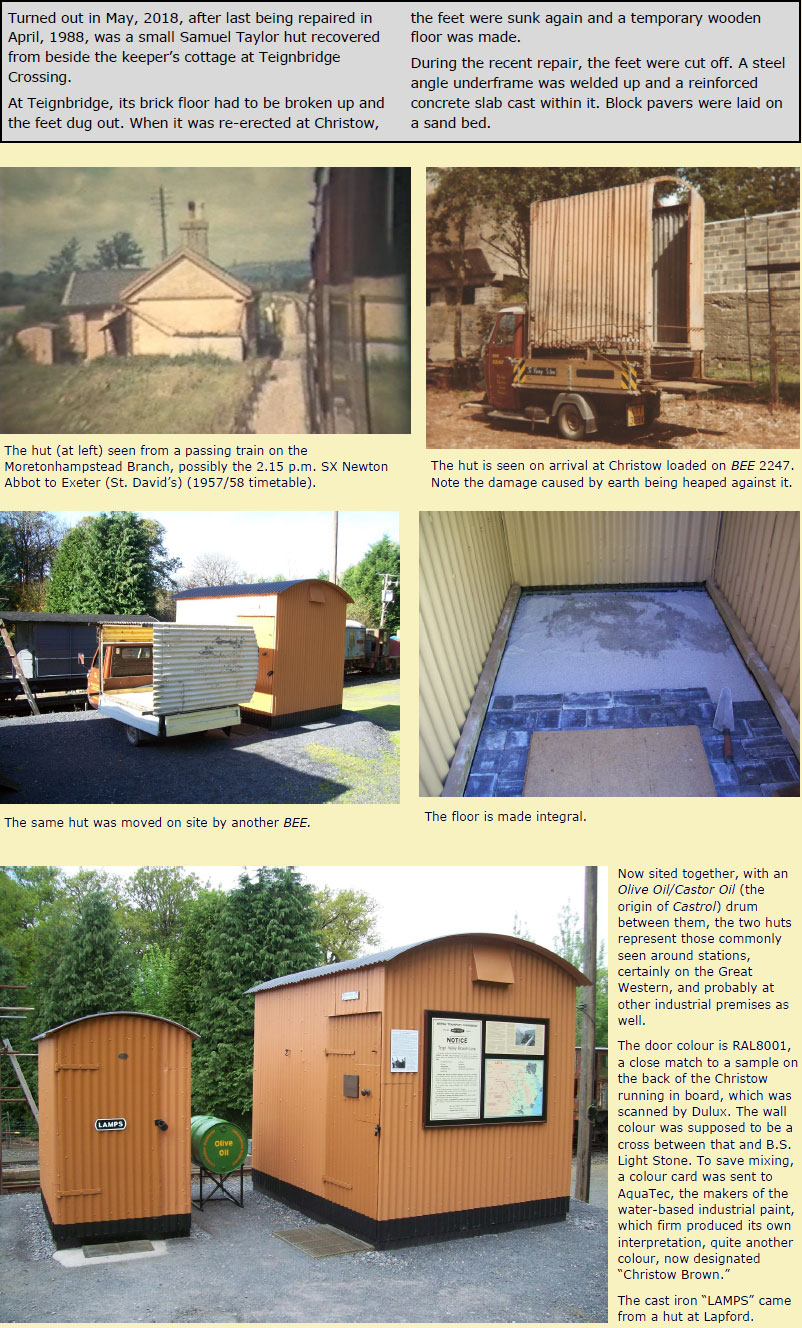

Repair and re-erection of Lamp Hut>> Lamp Hut >>

A store for the Building Department>> Another Trolley Shed >>

Running-In Boards>> Running-In Boards >>

Repair and alteration of G.W. brake van for Mr. N. Dudman.>> 17953 >>

Ganger's Occupation Key Box assembly>> Key Box >>

Building Department workshop>> WORKBOX 1944 >>

Repair of Collico cases>> B.R. Collico Service >>

Overhaul of narrow gauge turntable>> Narrow Gauge Turntable >>

Repair and modification of Temporary Booking Office>> WORKBOX 6638 >>

General Repair and modification of MUSSEL 4768>> MUSSEL 4768 >>

Telephone cabinets>> Telephone cabinets >>

General Repair of WHELK 5210>> WHELK 5210 >>

Repair of narrow gauge flat wagons>> SHRIMPs 3422 & 3425 >>

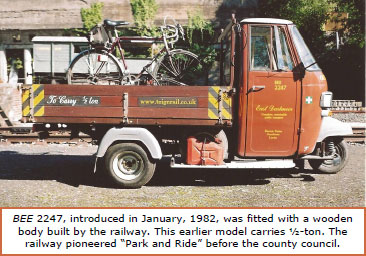

Overhaul of BEE 2247>> BEE 2247 >>

Overhaul of BEE 2309>> BEE 2309 (Overhaul) >>

Staff accommodation roof repairs>> WASP S 4943 >>

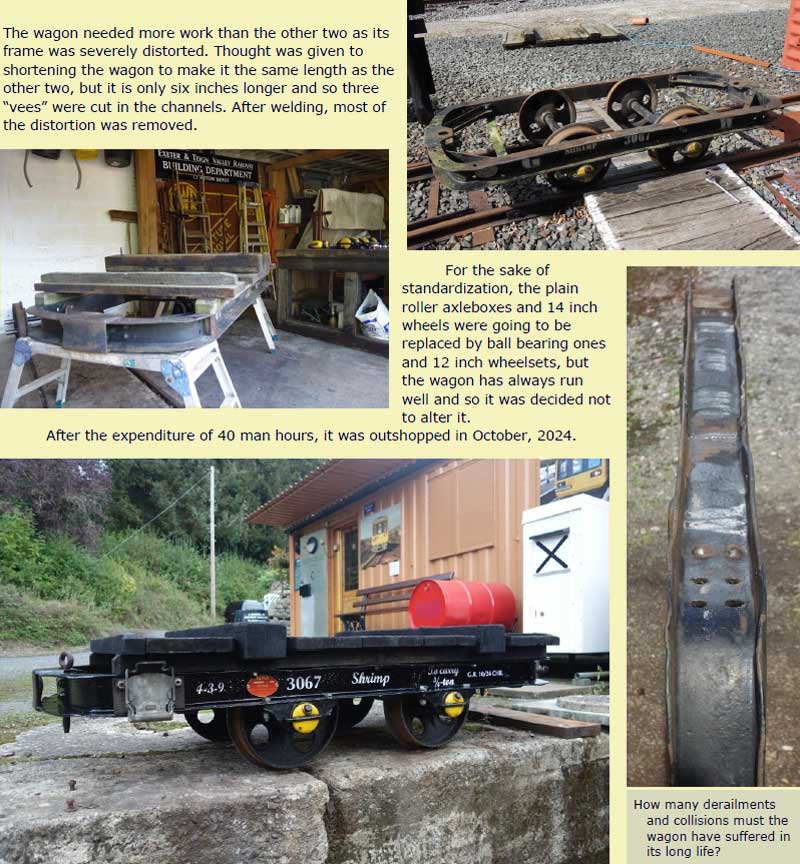

General Repair of SHRIMP 3067>> SHRIMP 3067 >>

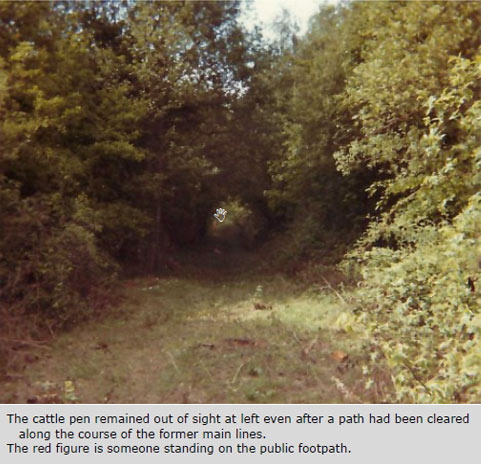

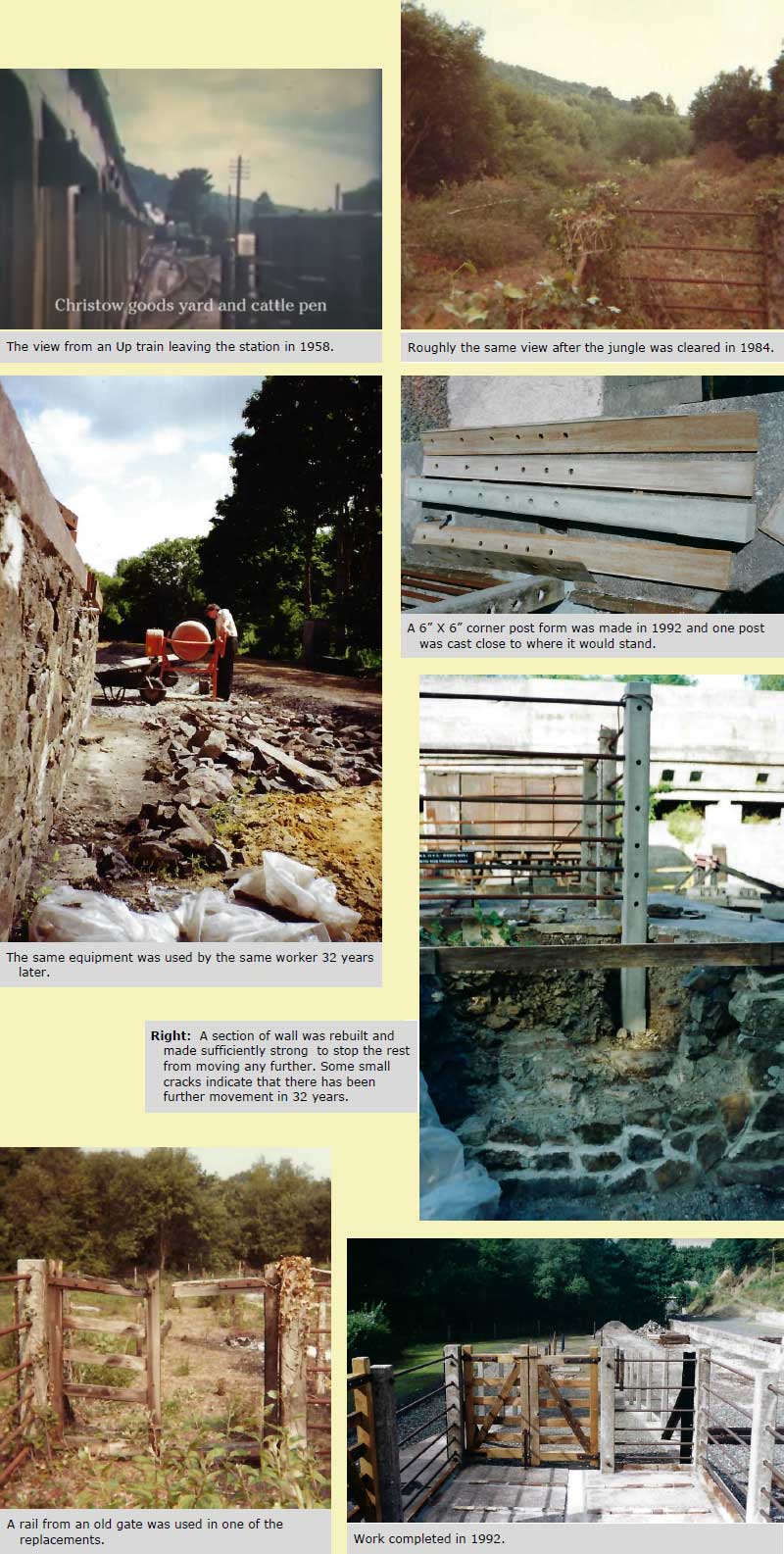

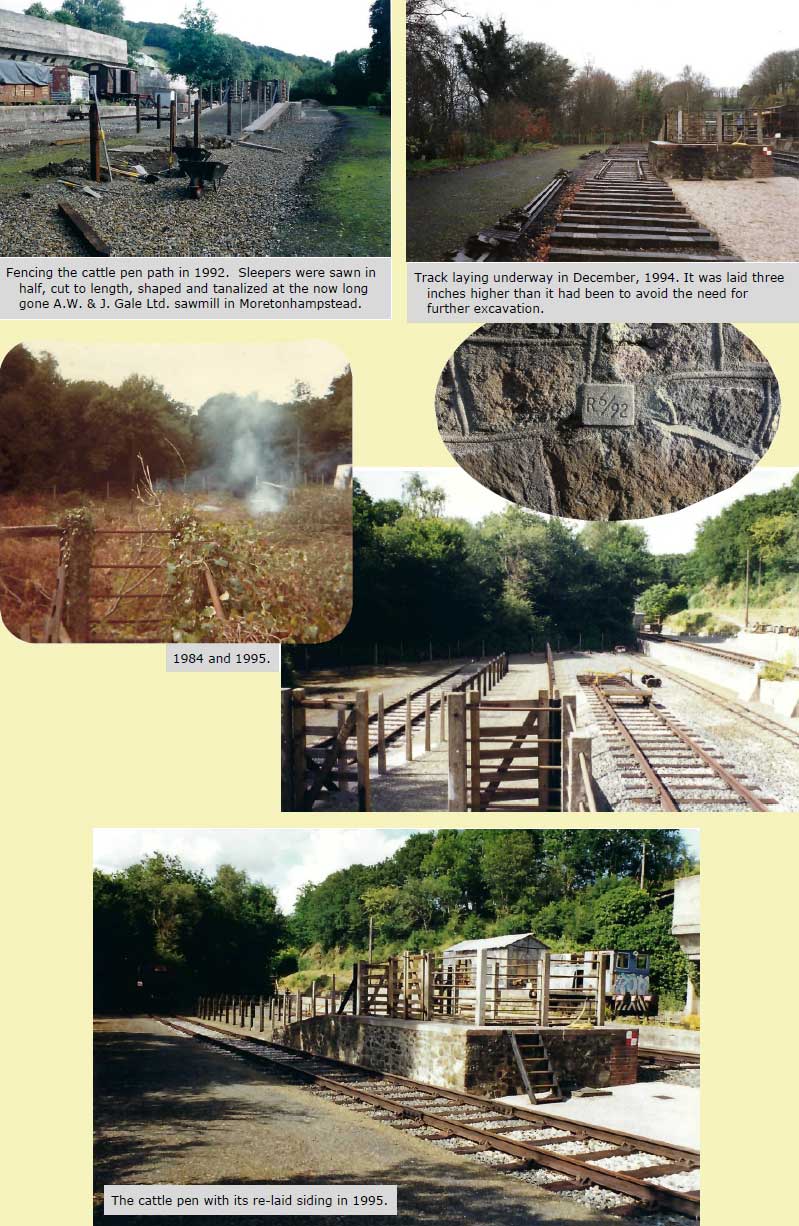

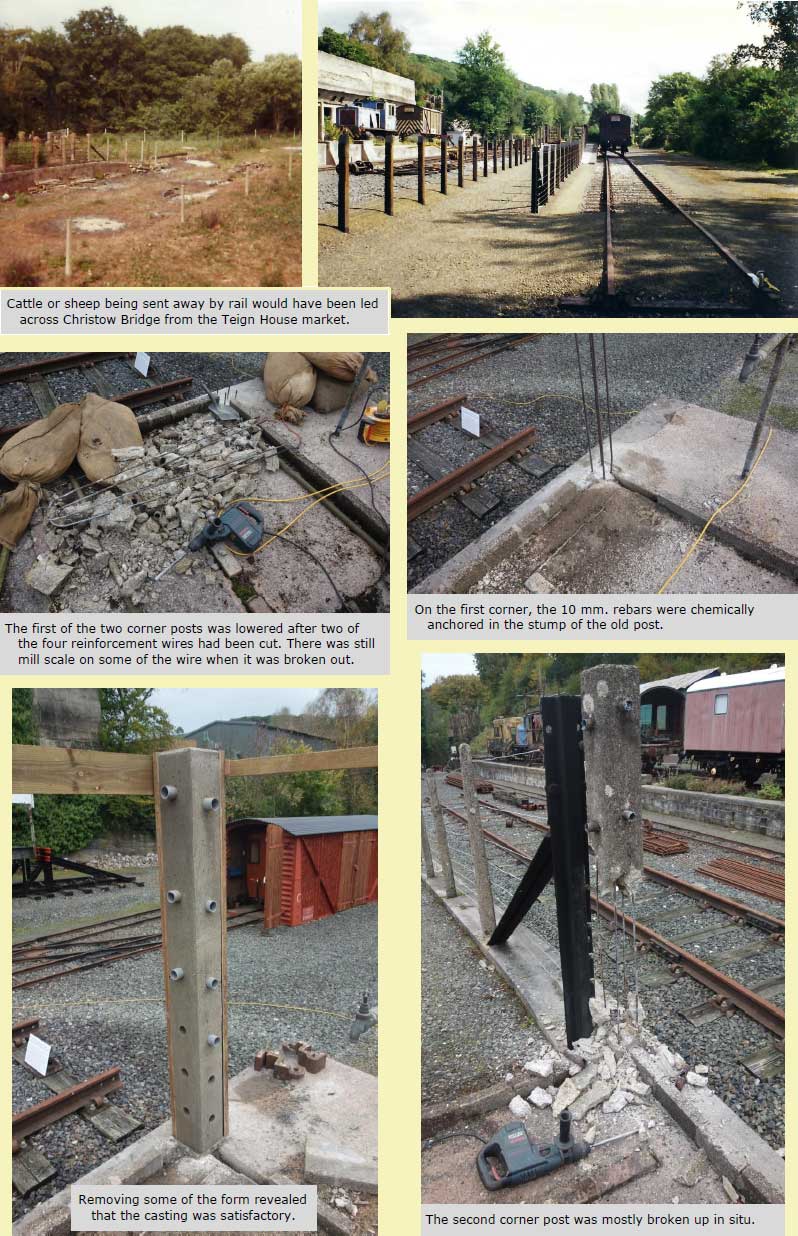

Repairs to Cattle Pen in 1991 and 2024>> Cattle Pen >>

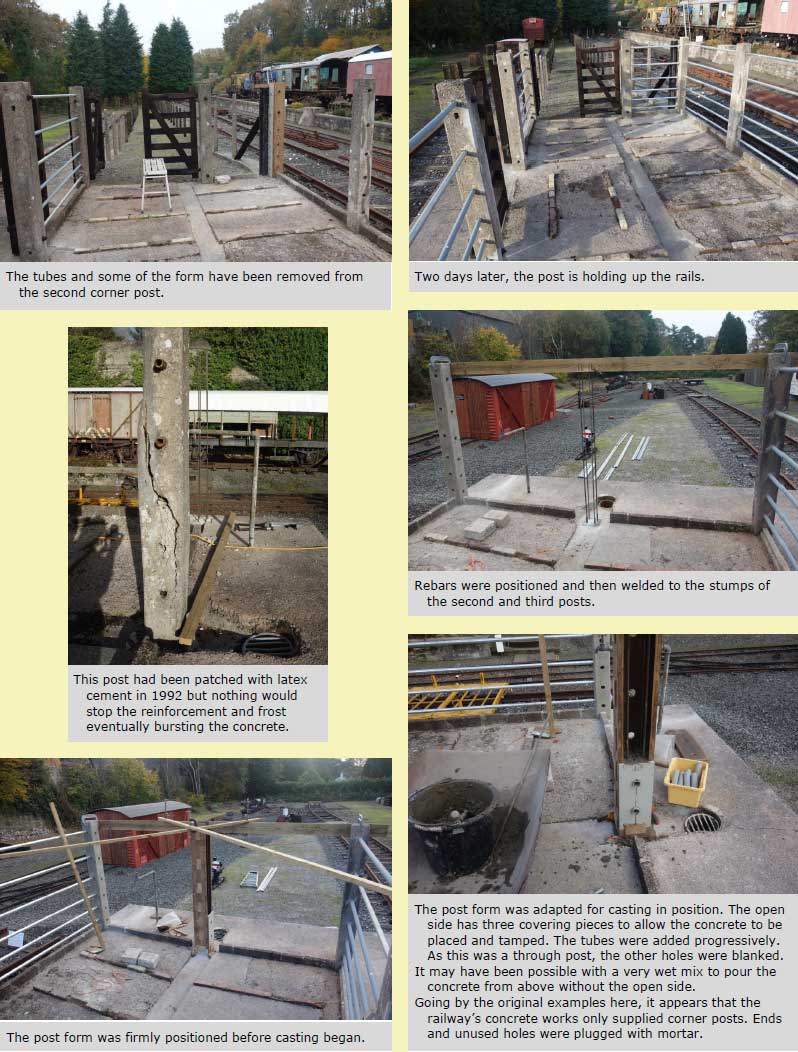

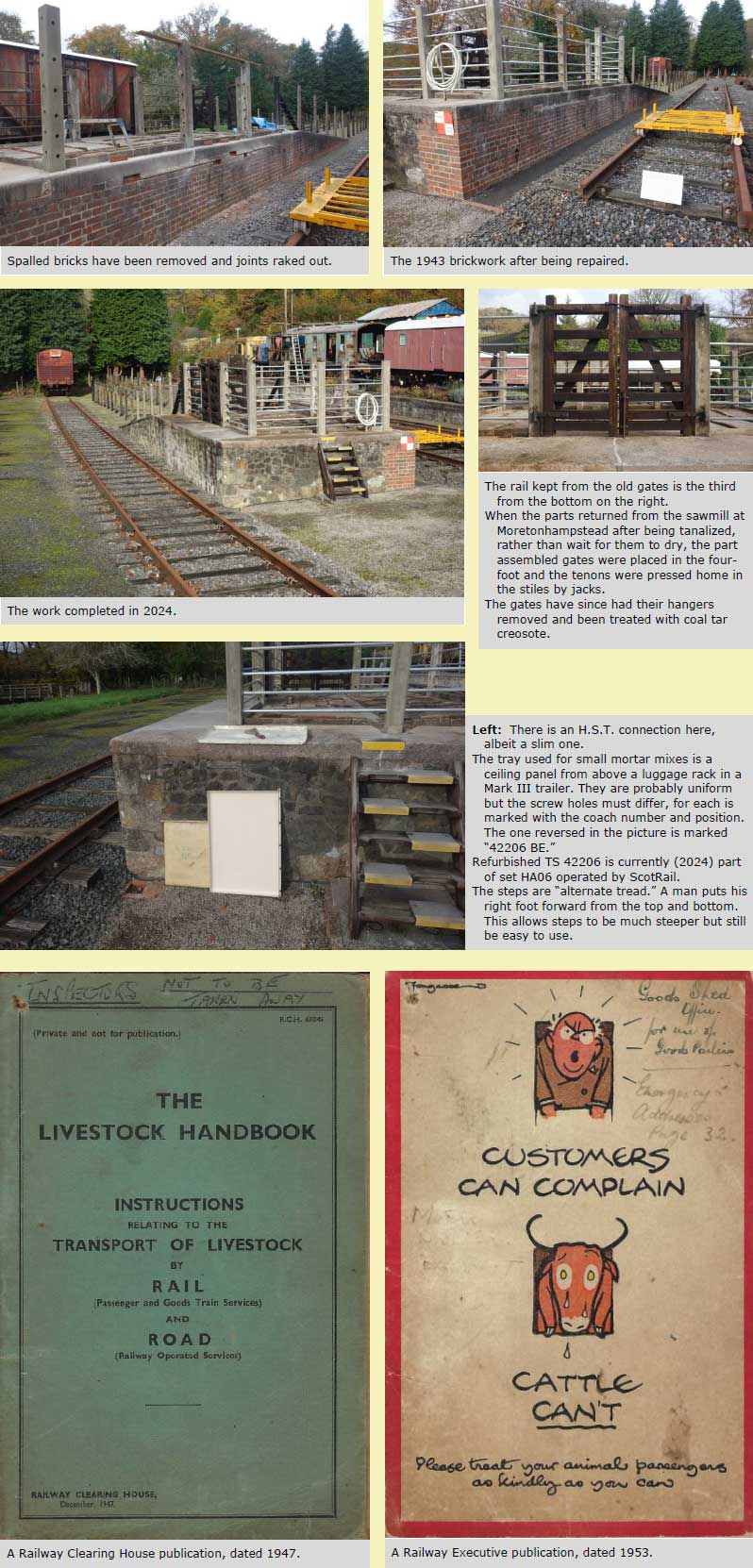

General Repair of Dobbin Barrow in 1991>> Dobbin Barrow >>

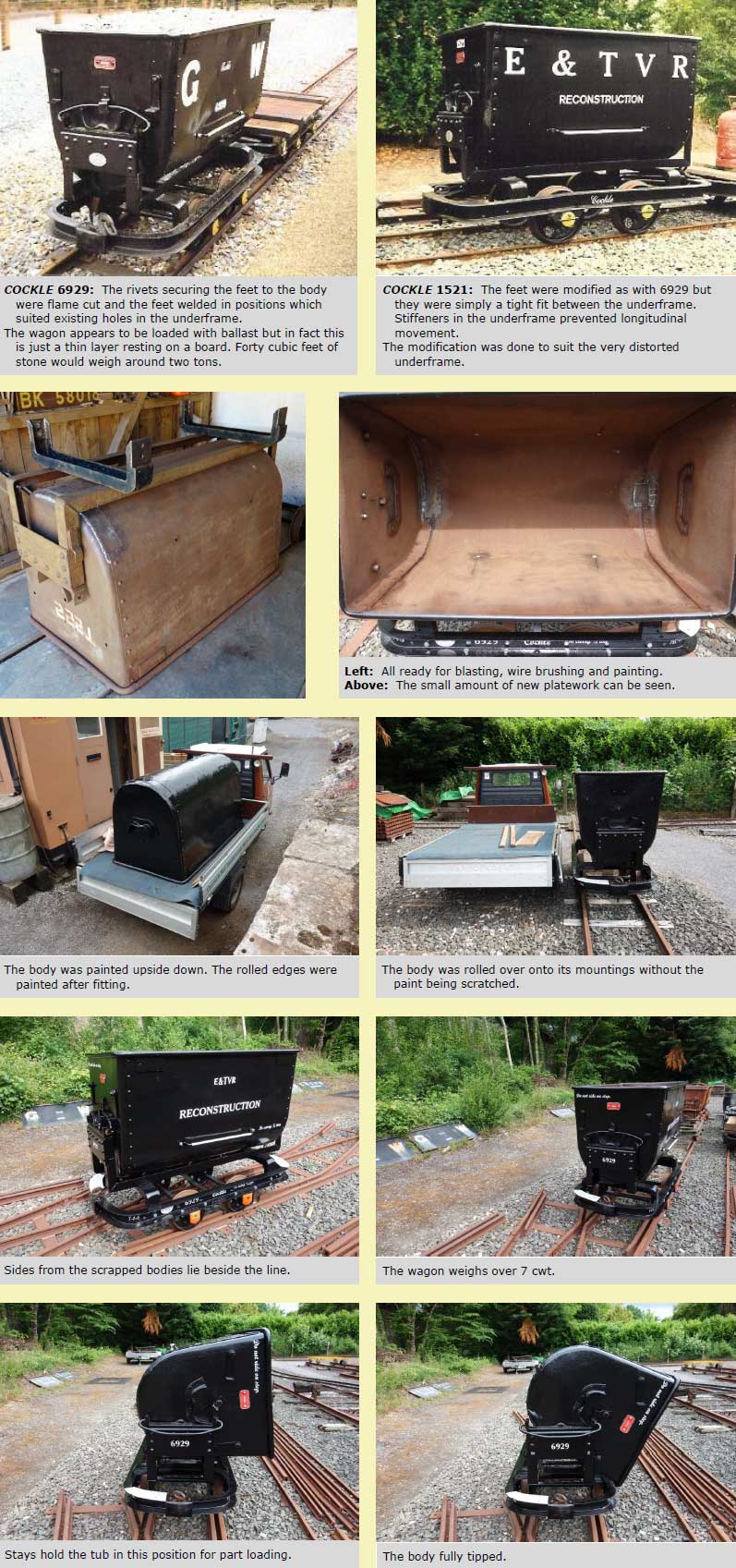

General Repair of COCKLE 6929>> COCKLE 6929 >>

LIMPET 6994>> LIMPET 6994 >>

>> Some of the Work on Show at Christow >>

BEE 2309

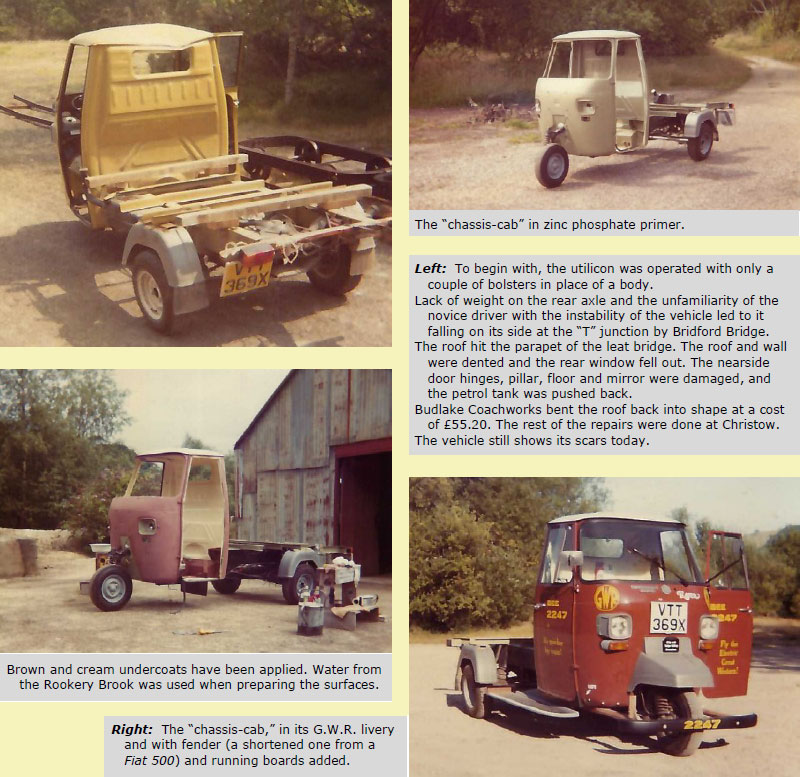

Commissioning work on the railway’s “new” autotruck, BEE 2309—done like most jobs, in many instalments—was completed in 2011. This vehicle replaced BEE 2247 which had been in service since 1982.

The new truck was supposed to have been supplied with an aluminium floor but came with the usual pressed steel plate, spot welded to the frame. On the model it was understood had been ordered, the aluminium floor was held down by the drop sides and could be lifted up to give complete access to the engine and underframe. The steel floor had only a poorly fitting hatch.

The fixed headboard and rack, and the floor plating, were removed. A new headstock and a detachable steel and plywood headboard, incorporating a full-width ladder rail, were made. A one-piece detachable plywood floor with aluminium edging was fitted.

Numerous other modifications were made to equip the truck for railway service. A letter was sent to Piaggio, translated into Italian, pointing out some of the design improvements made in a British workshop so that their production line could be altered. No reply was received.

The truck was delivered wearing Empire Green, one of the three colours available—those of the Italian flag.

The new truck had been performing well and commissioning work was in progress when an outright failure occurred, luckily only three miles from shed and at a refuge. Coolant pouring onto the road appeared to be coming from the pump. After being towed back to shed and dismantled, a complete seizure of the pump, driven by the timing belt, was confirmed as the fault.

The firm in Darlington that supplied the truck had closed down. Fortunately, Robin, the former boss, had taken on the Piaggio business as a sideline and was able to provide parts. But this was late July and the factory in Tuscany was preparing for its August shutdown. When the new pump arrived, the timing belt in stock was found to be the wrong one. It was mid-September before the truck went back into service.

Either it was a faulty pump or the timing belt had been over-tightened during factory assembly; the checks that had been made were looking for slackness and the tension was assumed to be correct as it was. The tell-tale sound of impending failure was like stone chips hitting the frame (probably coolant being expelled through the bearings), which is not much use as an indicator when it’s the season for dressing the roads.

This has greatly burdened the operating costs; the material cost of the repair was not too great but many service station tools had to be obtained. The diesel Ape is more expensive to buy and maintain but uses much less fuel than the petrol one. Whether this will be enough to tip the overall costs in favour of diesel is yet to be determined.

From Naples to Newton Abbot

Can it run on olive oil?

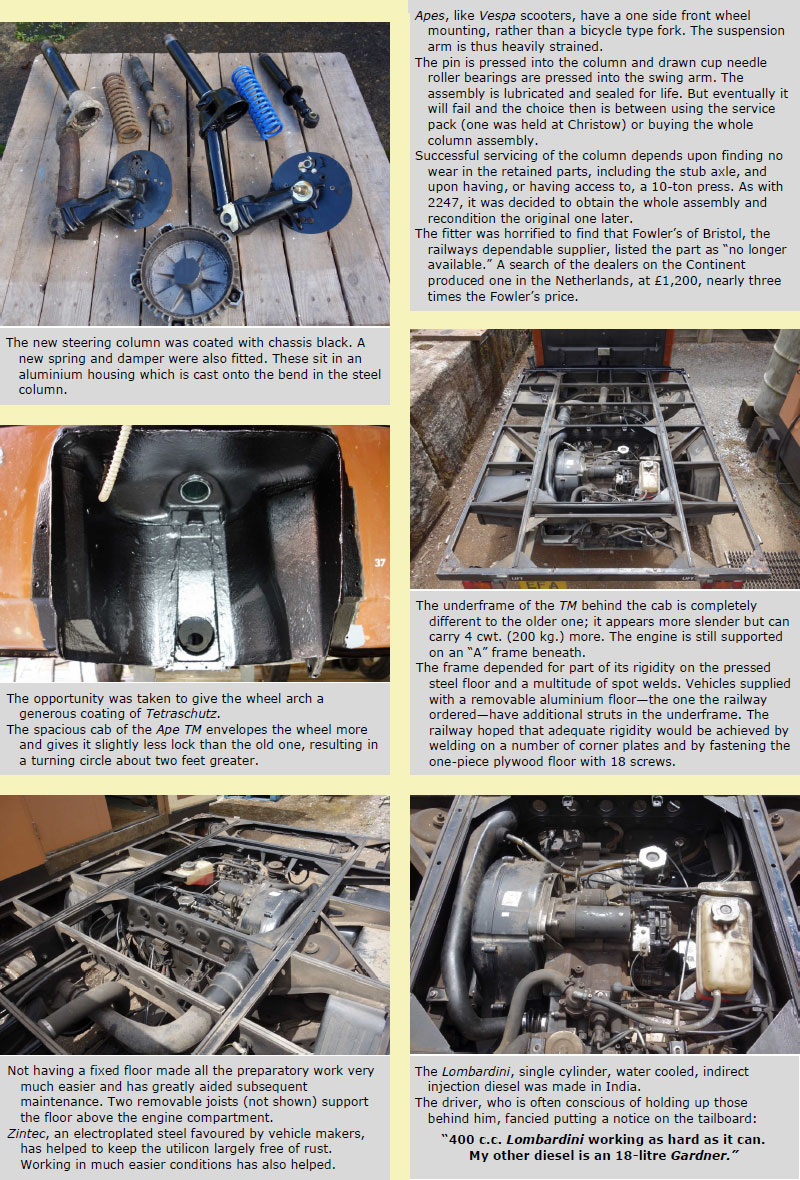

Rinaldo Piaggio's ship-fitting and coach-building firm, founded in 1884, turned to aviation in 1914. During the Second World War, the huge plant at Pontedera, Tuscany, manufacturing military aircraft, was razed to the ground by allied bombing.

In the post-war reconstruction of Italy, Piaggio saw the need for cheap motor transport and invented the all-enclosed motorcycle made from pressed steel—what became the "scooter."

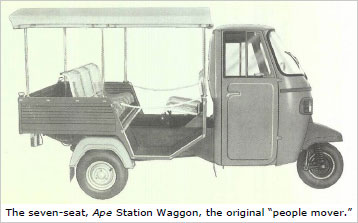

The Vespa (Wasp) was developed into the goods three-wheeler, the Ape (Bee) in about 1947, from which the railway's modern example is descended.

Still offered today is the simple two-stroke petrol engine, which from the late 1970s has had lubrificazione separata and electronic ignition for greater reliability. But higher performance has been achieved with a Lombardini single-cylinder diesel made especially for Piaggio. Both engines drive through an integral five-speed gearbox.

The diesel is more expensive to buy and maintain but uses less fuel; the railway’s has so far turned in an average of 86.3 miles per gallon.

These trucks are designed to carry ¾-ton in addition to the driver and a passenger. A variety of bodies is available from the manufacturer, including a box van, hydraulic tipper and dust cart.

These trucks are designed to carry ¾-ton in addition to the driver and a passenger. A variety of bodies is available from the manufacturer, including a box van, hydraulic tipper and dust cart.

The railway's new model, delivered in December, 2007, replaced one introduced in 1982, which remains serviceable but is confined to shed. Much preparatory work and modification had to be done to fit the new one for railway service.

Unlike in the home market, where Italian authorities, utilities, tradesmen, roundsmen, vendors, growers, etc., buy the Ape because it is the most suitable for the job, Britain has very largely shunned them and carried on using vehicles which are often much larger and more expensive than is necessary.

If a builder, for instance, who only really needed a ¾-ton capacity for local work replaced his Transit or Cabstar with one of these, then he would occupy half the road space and save three-quarters of the fuel.

If a builder, for instance, who only really needed a ¾-ton capacity for local work replaced his Transit or Cabstar with one of these, then he would occupy half the road space and save three-quarters of the fuel.

And could it not be such small trucks or vans as these that in future radiate from stations collecting and delivering parcels and light goods traffic?

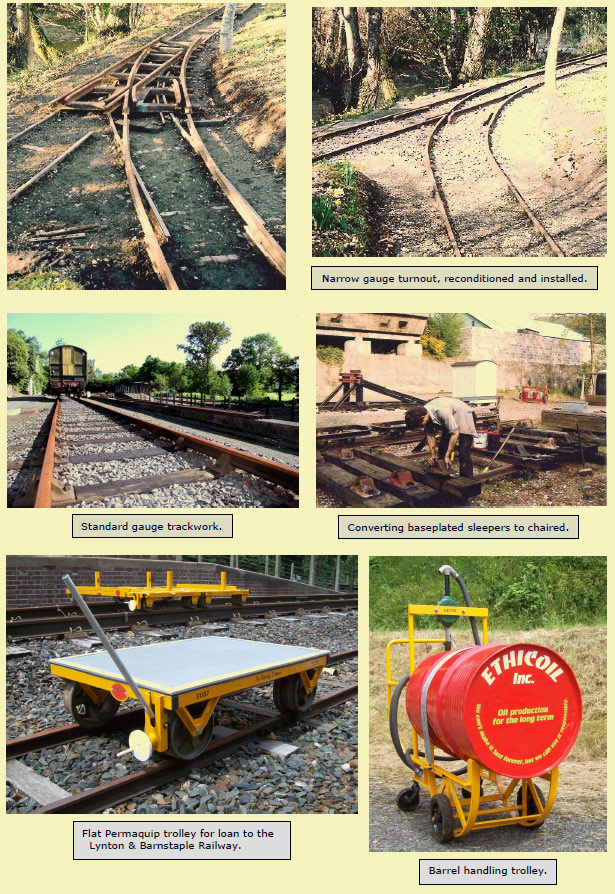

GANGCAR 194

(PWM 2831 & Trailer No. 755)

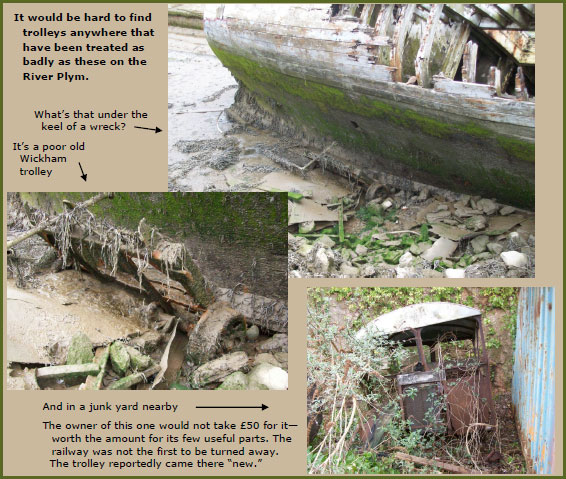

Describing the work on the railway’s Type 27 trolley as a factory rebuild, as what the factory would have done had the trolley been returned there, to distinguish the class of repair, is somewhat hypothetical, for Wickham’s would actually have had no option but to condemn it as beyond economic repair.

It is hard to believe that such a vehicle was still in service with the nationalized railway. Dear old British Rail could scrap locos and rolling stock prematurely, writing off enormous capital sums, yet allow a forty year-old wreck to carry staff on rail at a time when new substitutes were available and the safety regime was tougher. It is also a wonder that a non-standard 1949 trolley should have been kept when newer types were scrapped or sold to private railways.

The trolley must have suffered several severe collisions; even the roof was crushed. Frame and body sections were broken and buckled. The front wheels were so out of round that the trolley hopped along the track. The sand boxes had been smashed; springs had broken; bearings had failed; many parts were missing; every remaining part needed attention. Almost at a glance, a Wickham inspector would have seen enough to make his unsentimental pronouncement.

The trolley must have suffered several severe collisions; even the roof was crushed. Frame and body sections were broken and buckled. The front wheels were so out of round that the trolley hopped along the track. The sand boxes had been smashed; springs had broken; bearings had failed; many parts were missing; every remaining part needed attention. Almost at a glance, a Wickham inspector would have seen enough to make his unsentimental pronouncement.

So the railway has carried out an uneconomic repair, but the result is what the factory would have achieved, which is a trolley as near to new as possible with another 10-15 years of useful life.

The trolley was broken up on the track into pieces small enough to carry. Some heavy parts were straightened by eye while the torch was to hand. Later, the frame was cut and welded to restore its shape and strengthening plates were added. The rest of the trolley was reduced to its component parts and every one repaired and, or, modified, or replaced. New bearings, springs and bushes were fitted; journals were built up to take metric bearings; the chain and driven sprocket were replaced.

The trolley was broken up on the track into pieces small enough to carry. Some heavy parts were straightened by eye while the torch was to hand. Later, the frame was cut and welded to restore its shape and strengthening plates were added. The rest of the trolley was reduced to its component parts and every one repaired and, or, modified, or replaced. New bearings, springs and bushes were fitted; journals were built up to take metric bearings; the chain and driven sprocket were replaced.

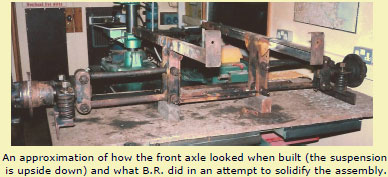

For some reason, as yet undiscovered, this trolley was built with front stub axles, an uncommon and unwise practice with railway vehicles. A solid, through axle would have fouled the engine sump. A cranked axle beneath the sump would have fouled A.T.C. ramps. So why was the engine not raised? Why was not an axle split horizontally around the sump fitted?

The challenge for the railway was either to correct a flawed design (Wickham’s must not have continued with it) or somehow to connect the stub axles. The hubs depend for their restraint in a vertical plane on a parallelogram arrangement which describes a small arc easily taken up by the slack in the suspension bushes. The radius rods were finely made and in good condition. In a crude attempt to lock up the suspension, B.R. men had fitted opposite diagonal braces. All these did was to transmit shock and twisting action to frame members, which then split or fractured.

The challenge for the railway was either to correct a flawed design (Wickham’s must not have continued with it) or somehow to connect the stub axles. The hubs depend for their restraint in a vertical plane on a parallelogram arrangement which describes a small arc easily taken up by the slack in the suspension bushes. The radius rods were finely made and in good condition. In a crude attempt to lock up the suspension, B.R. men had fitted opposite diagonal braces. All these did was to transmit shock and twisting action to frame members, which then split or fractured.

It was decided that the challenge was to make the original design work. This has yet to be proven in service.

An attempt was made to turn the very worn Wickham wheels but this was abandoned in favour of fitting new Fairmont wheels, using conversion discs to take up the difference in centres and the number of studs. The Fairmont wheels have less float and only 1° of conicity.

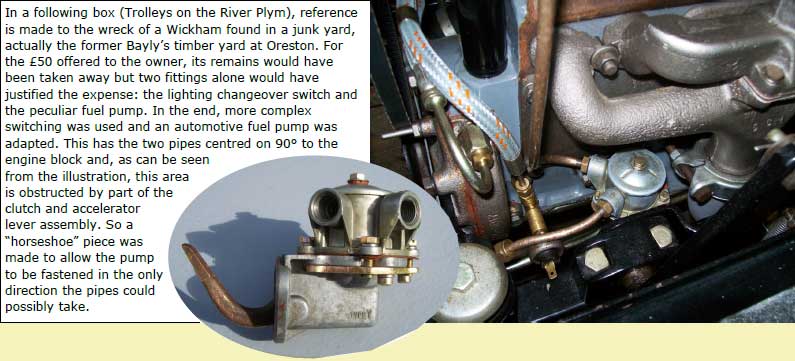

The major weakness in the rebuilding process was the engine; Wickham's would hardly have sent the trolley out with a reconditioned Ford side-valve. The railway looked at fitting a two-cylinder Lombardini diesel but the space available seemed to crave a Ford to go with the existing clutch and gearbox, themselves integral with the direction box.

The major weakness in the rebuilding process was the engine; Wickham's would hardly have sent the trolley out with a reconditioned Ford side-valve. The railway looked at fitting a two-cylinder Lombardini diesel but the space available seemed to crave a Ford to go with the existing clutch and gearbox, themselves integral with the direction box.

This is not as bad as it sounds. The Ford E93A, introduced in 1938, still has engineering support and can be fully reconditioned, thanks to its enthusiast following. It will run on unleaded petrol. The engines were meant by Ford to be service-exchanged at around 30,000 miles and the trolley had a reconditioned unit. The application is relatively undemanding.

After trying to get the engine rebuilt locally, a replacement was obtained from a Ford "Pop" specialist. This was fitted with an oil bypass filter and electronic ignition. The railway has the other engine to send away for reconditioning if necessary.

The trolley was outshopped with riveted aluminium plating, additional glazing at the front for close track inspection, halogen and L.E.D. lighting, dual arm wipers (designed specially by Andrew at Britax), p.v.c. side curtains and overall cover, and a sprung coupler.

The trolley was not built with running boards. The railway considered that they would be incongruous and unnecessary. As it is, the trolley has a compact width of 5’ 9”. Any man who is not fit enough to get onto the trolley from sleeper level should not be on the track.

The unsprung trailer which completes unit 194 was finished in 2006. It needed new bearings, side rails, plywood flooring and repairs to the solebar ends. A ratchet brake mechanism from an old platelayer's trolley found burnt up at Uffculme has been modified to act on one wheel. New draw eyes were rodded together to spread the load to both headstocks. The two-foot coupler enables longer timbers to be carried on the trailer.

The unsprung trailer which completes unit 194 was finished in 2006. It needed new bearings, side rails, plywood flooring and repairs to the solebar ends. A ratchet brake mechanism from an old platelayer's trolley found burnt up at Uffculme has been modified to act on one wheel. New draw eyes were rodded together to spread the load to both headstocks. The two-foot coupler enables longer timbers to be carried on the trailer.

The trolley had a dowel beneath the driver’s seat and two aluminium cradles beneath the rear seat for stowage of the turntable. Original parts were measured up at Buckfastleigh and an “Improved Wickham Turntable” made at Christow. The turntable centre has a captive disc, floating on grease, on which the beam rests. The ends of the rails are articulated, so that when turning the clips are folded out of the way and when stowed the rails do not overhang. It has been tested up to 17 cwt.; the trolley weighs 16 cwt.

Design knowledge can be made available to Wickham owners. Prices can be quoted for new parts or for various grades of repair.

D. Wickham & Co. Ltd. was a general engineering firm which progressed into railcar manufacture as part of a diverse business.

Perhaps best known for its lightweight trolleys, some of its 11,723 rail vehicles were passenger-carrying diesel multiple units.

Like many British factories, much of Wickham’s output was for overseas administrations. Of the home market, there was much demand from mines and government ministries. Sales to British railways were quite small: the G.W.R. and B.R. Western Region altogether ordered 413 trolleys and trailers of various types between 1929 and 1961.

The trolley latterly stationed at Christow was a Type 17 (Wickham No. 4993) produced in May, 1949, only four months before the railway’s Type 27 (No. 5009) which came here by way of Oswestry, Neath and Exmouth Junction.

Wickham works plates can still be found on dilapidated trolleys at private railways around the country and on vehicles in many far-flung corners of the world. Even in a lonely shed on Dartmoor, at the end of a narrow gauge track on the military ranges, resides a Wickham target trolley (No. 3284, built 1943).

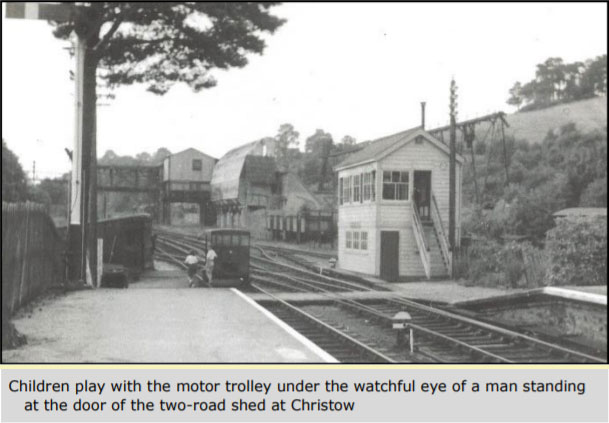

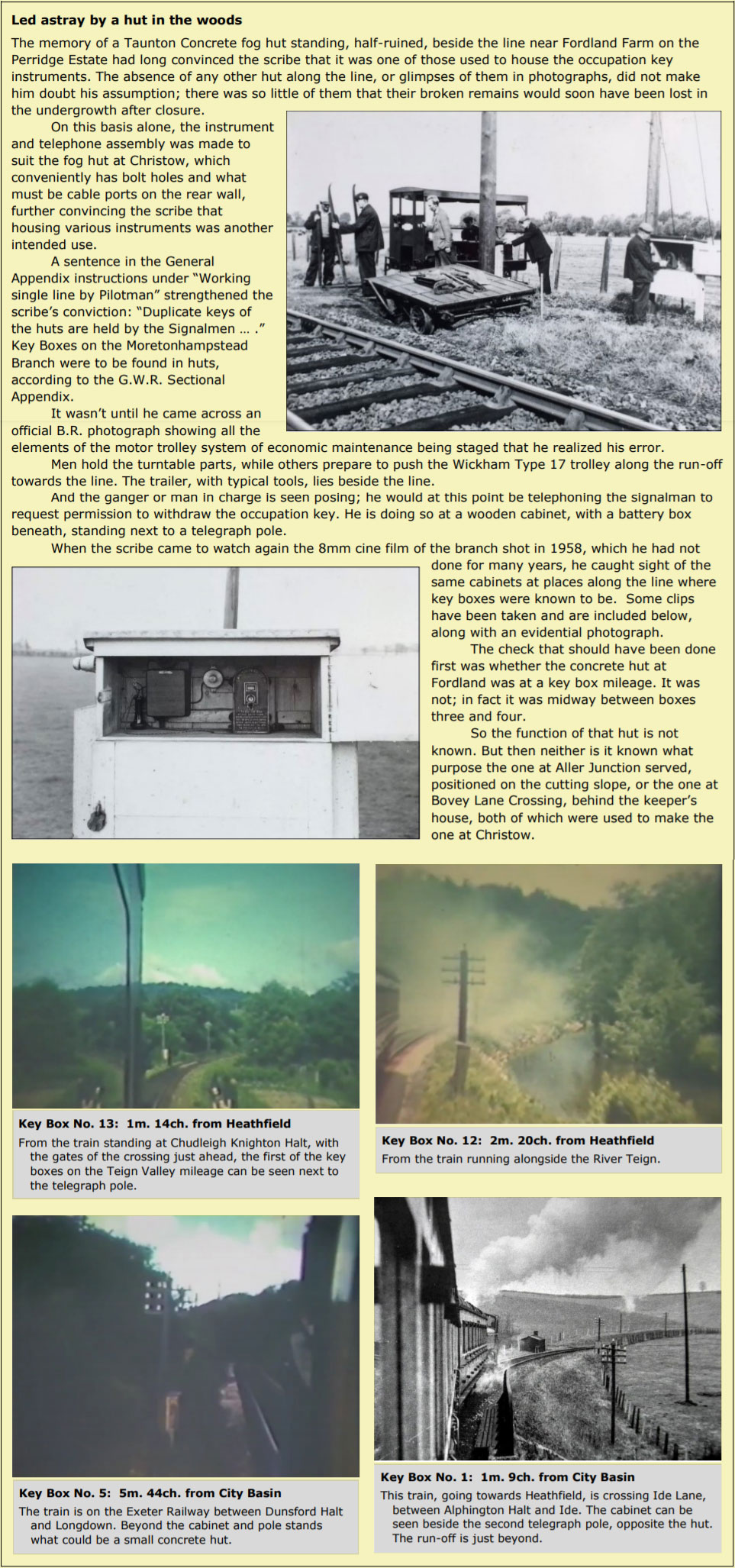

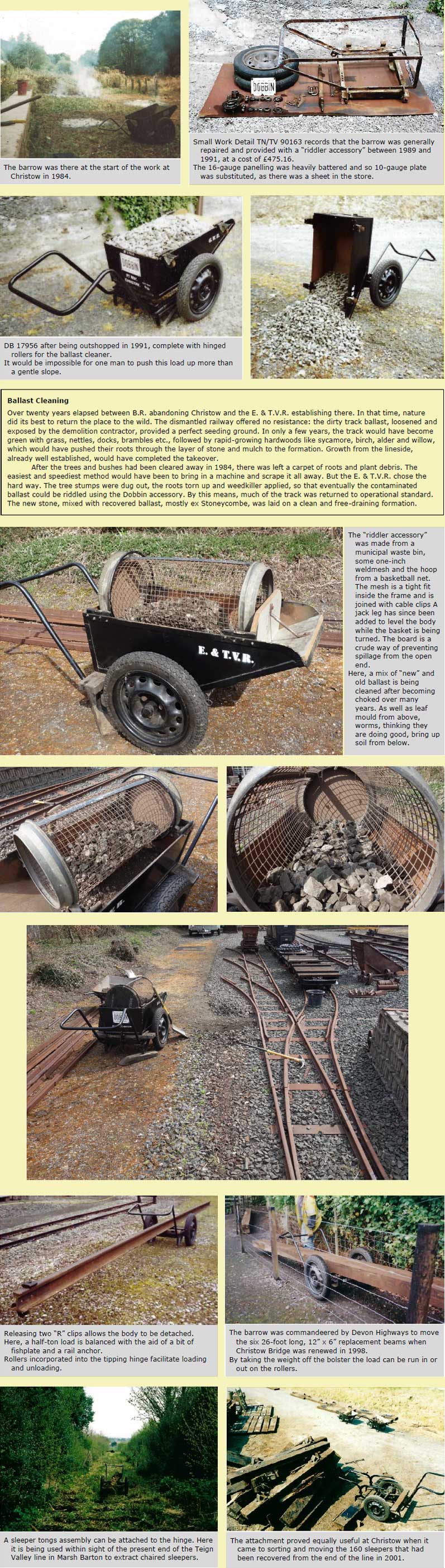

The "Economical" or "Motor Trolley" System of Maintenance was introduced by the Great Western Railway on some single lines to dispense with the numerous local gangs, to save manpower and to facilitate occupation of the line.

The system was brought into use on the Teign Valley Branch on 1st April, 1935, with the establishment of an eleven-man gang at Christow and the stationing here of two petrol motor trolleys.

The system was brought into use on the Teign Valley Branch on 1st April, 1935, with the establishment of an eleven-man gang at Christow and the stationing here of two petrol motor trolleys.

The trolleys were kept in a hut at the end of the Up platform and were lifted on and off the rails by hand. One was used by the ganger for his daily inspection and the other by the gang to go to the site of work, a trailer being provided for the conveyance of tools and materials.

These trolleys could only be run on the line after withdrawal of a Ganger’s Occupation Key from one of the Key Boxes located at the signal boxes and in huts along the line at approximately one-mile intervals, and released by the signalman in the controlling box by means of a Control Instrument. When the Ganger’s Occupation Key was withdrawn, the Electric Train Staff for the relevant section was locked in the instrument, and vice-versa.

The system dispensed with the need to provide lookout men, as no train could enter an occupied section without the Train Staff, and enabled trolleys to be run off at intermediate places to allow the passage of trains.

The system could also be used in the case of any operation which would interfere with the running of trains and in an emergency, such as an earthslip or failure of the works, when the withdrawal of the occupation key would afford the necessary protection.

Some branches, such as the neighbouring Moretonhampstead, had the same control system in place but were not equipped with motor trolleys.

The Open Road

The Open Road

There were times, it has to be confessed, during the course of a long, drawn out job, when a moment was taken to sit in the driver’s seat and dream of what it would be like to motor off along a pair of rails that appeared to converge in the far distance. There were times when it looked like it would never happen. If it ever did happen, it was imagined that it would be great fun.

In 2011, the West Somerset Railway was persuaded to take the trolley to see if it would prove useful to the Permanent Way gang. The General Manager had always wanted to ride over his line in “one of those things,” so it was assumed that there would be a few Teign Valley friends’ excursions in the course of a year which would be the reciprocal favour.

In 2011, the West Somerset Railway was persuaded to take the trolley to see if it would prove useful to the Permanent Way gang. The General Manager had always wanted to ride over his line in “one of those things,” so it was assumed that there would be a few Teign Valley friends’ excursions in the course of a year which would be the reciprocal favour.

However, the only use it ever saw in a year’s stay at Dunster was as part of a brief training session, when, with the driver and five West Somerset men, the trolley made a test run to Blue Anchor and back. For he who had dreamed, it was one of those rare cases of anticipation being matched by the event.

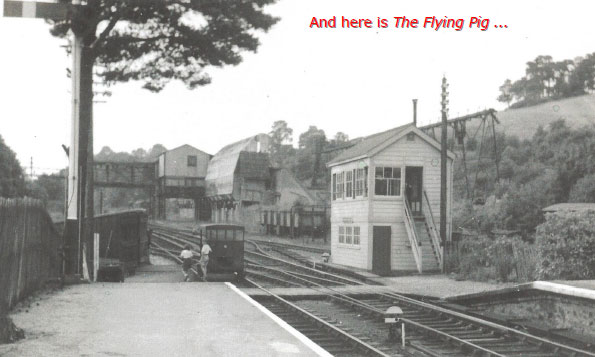

The Flying Pig

It would not do to overstate the importance of these humble vehicles in the overall scheme, but in fact their contribution and prominence, on the lines where they were stationed, is hardly recognized at all.

On this branch, the trolley would have been seen in a siding or on a run-off somewhere from any train taken during working hours, with the gang about its work nearby. Normally, the trolley would be the only movement seen on a Sunday, the men gleefully making time and three-quarters. For the longest-standing resident here at Christow, the sound of one of J.A. Prestwich’s (JAP) engines and the return of "The Flying Pig," as it was dubbed, marked the approach of four o'clock.

On this branch, the trolley would have been seen in a siding or on a run-off somewhere from any train taken during working hours, with the gang about its work nearby. Normally, the trolley would be the only movement seen on a Sunday, the men gleefully making time and three-quarters. For the longest-standing resident here at Christow, the sound of one of J.A. Prestwich’s (JAP) engines and the return of "The Flying Pig," as it was dubbed, marked the approach of four o'clock.

Yet most of the heritage railways which profess to recreate the look of times gone by make no attempt to demonstrate the Motor Trolley System. Most trolleys are kept by individuals in pursuit of a hobby akin to messing about with cars. Though many trolleys survive, most are not looked after; some are shoddily repaired; others are decrepit; few run regularly.

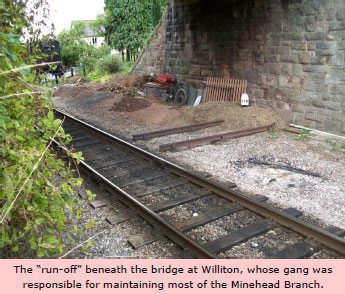

The West Somerset Railway, which was maintained between Bishops Lydeard and Blue Anchor by a motor gang, does not even have a trolley. When the E. & T.V.R. Gangcar was foisted upon it, the vehicle sat at Dunster for a year, moving only once. It had been hoped to use the remaining home run-off under the bridge at Williton, which is due to be removed, but no-one was really interested.

Above, the Christow gang trolley is seen outside its shed opposite the signal box. This trolley was a Wickham Type 17 (Works No. 4993, B.R. Nos. B178/PWM2815), the most commonly produced. It had side-facing bench seats and a JAP engine. It was turned out of the works at Ware in Hertfordshire in 1949, only four months before the one that resides today at Christow.

The standard shed, roughly-built out of sawn sleepers, had two “roads” with a small store at the far end. A permanent way man can just be seen opening the double doors. The shed also housed the small ganger’s inspection trolley, but the identity of this is a mystery. The “four-foot” outside the shed was filled in with timbers. Unlike the Type 27s, the 17s were light enough to be lifted at one end and so could be bumped around to face the shed; the collapsible turntable was used at run-offs. Its trailer was left outside the shed at this end and at the other was a small stocking area where maintenance materials were kept.

The former Scatter Rock Macadams’ quarry had closed in 1950 and the railhead works seen in the background here were disused. The sidings remained until 1957 and were used latterly by Laporte Chemicals for loading barytes from Bridford Mine being sent to Luton. The steel-bodied minerals seen beyond the signal box are berthed beneath a high platform from which the mine lorry could tip. Wagons had to be thoroughly cleaned for this traffic and the wagons have their doors dropped, suggesting this work is being done.

Platform Trolleys

Who among men of a certain age has not sat on a battered old trolley at the end of a sunny platform or quietly played with the handle to test the brake?

Made redundant at Exeter Central, the trolley at Christow was bought from British Rail on 10th August, 1977, for £5.40. It was carried unquestioningly by four men from the edge of the Down platform across to a covered wagon on a trip working standing on the remaining through line and later unloaded in the Transfer Shed at St. David's, where it was repaired and repainted in the project's unofficial store. Before it was taken to Longdown, the trolley was wheeled over Red Cow Crossing and up the ramp of No. 1 platform to be weighed outside the Parcels Office. Its fake "Carriage Free on Company's Services" label was spotted by a zealous young manager who caused a "please explain" memo to be sent. Of course, it was easily explained that there had not been a train to Longdown for nearly 20 years.

This one is the survivor of around six that the railway has possessed and the only one whose body was not badly rotten. If left in the open, the conventionally jointed softwood frames of these trolleys were extremely vulnerable: rainwater would get under the boards and into the joints and eventually the frames would succumb to wet rot.

While working on this one again, nearly 40 years after it left Central Station, it became obvious that the practice was to make new bodies and use turntables, axle bolsters and ironwork recovered from old trolleys sent back to Swindon.

The picture comes from a booklet on Swindon Works published by B.R. in 1957. On a bench behind the joiners can be seen a stack of six trolley bodies. It was long taken to be a contemporary photograph but much more likely is that it was a G.W.R. pre-war shot; it is doubted that any new trolleys were made after the war so the ones found today must all be at least 80 years old, with parts possibly dating back to the 19th century.

The trolleys were extremely heavy and poorly designed. They ran on cast iron wheels with plain bearings which were seldom oiled; some had solid-rubber tyred wheels which had "NOT TO BE OILED" marked on the handles. The automatic brake acted on the rear wheels and a clumsy mechanism connected them to the handle, which would spring back if let go. Nevertheless, the trolleys were such a common feature of stations that if none had survived someone would by now be building them just as they were.

To make the Christow trolley more useful on ground less perfect than the polished asphalt of busy platforms, new rubber tyred wheels with plain roller bearings have been fitted. And to make it more durable, the boards were sealed with liquid rubber in 1977, a product then new to the trade. Not having shown any signs of aging, this treatment has been repeated.

To replicate the one often seen in photographs of Dulverton, a canvas hood was made by Gray's of Exeter in 1978 at a cost of £18.20 and fitted to a free-standing, collapsible wooden frame made at Longdown. This sat on the boards within the edge rail and was the best that could be done at the time. Its replacement is a one-piece tubular frame which is slipped onto spigots welded to the half-round capping.

For years the one at Dulverton was the only one ever seen, but recently another was spotted in a photo of the Down platform at Witham. There must have been more but they were certainly scarce.

In later years, some trolleys at the big stations were fitted with couplings to enable them to be hauled by petrol or battery electric tractors and trolleys. Parts taken from a trolley found at Taunton Loco have been fitted for demonstration purposes; the rear coupling pin to the complete trolley and the front coupling eye to a handle and axle assembly.

The E. & T.V.R. attends to the detail of these small objects with more care than many of the so-called preserved railways.

The Great Western General Appendix of 1936 contains several pages of instructions relating to platform trollies (sic).

On automatic brakes, it states:-

The Station Master must depute a suitable member of his Staff TO BE RESPONSIBLE FOR MAINTAINING THE BRAKES IN AN EFFICIENT CONDITION.

The man appointed must test the brake on each trolley twice a week ...

Who would have wanted to be in the shoes of the man, one of whose trolleys had rolled off the platform onto the main line just as the signalman pulled off the back board for the fast?

D 2269 — work in progress

The new cab on the industrial shunting loco under repair will have a single door leading from an end platform. A long way ahead of the rest of it, one of the original doors has been repaired for exhibition purposes.

The loco was involved in an emergency services' exercise at Exmouth Junction which went wrong. A deliberate fire got out of control and damaged one side of the cab; the old door on the right still has charring. The sliding window and door droplight were replaced.

Of course, it would be that the door in the best condition was the wrong "hand" and so it had to have its stiles remoulded as opposites. The internal boarding is only 5/16 in. thick and so the tongues and grooves are very delicate. The new boards have a lovely figure but it remains to be seen whether they will warp.

Label: Diesel Mechanical, 0-4-0 Shunting Locomotive

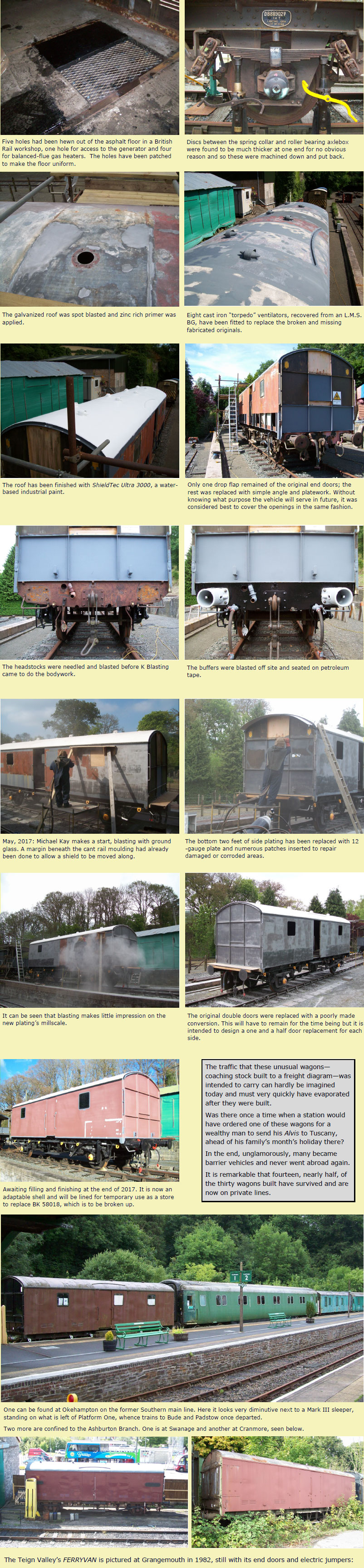

FERRYVAN 889027 — work in progress

www.flickr.com/photos/holycorner/sets/72157649035393338/

1928 Pumphouse

Lamp Hut

Motor Trolley Shed

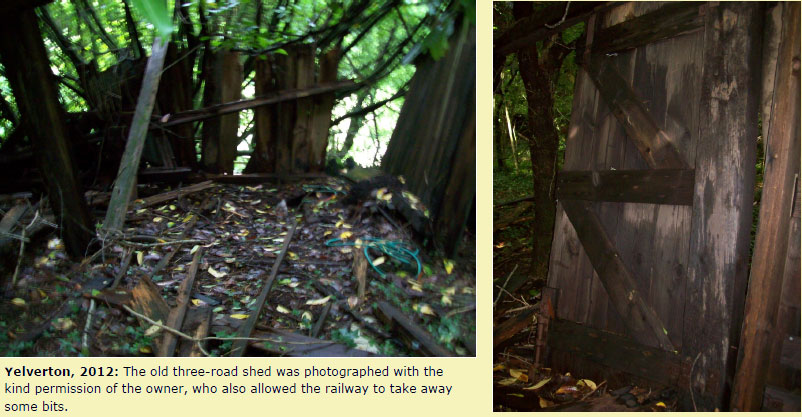

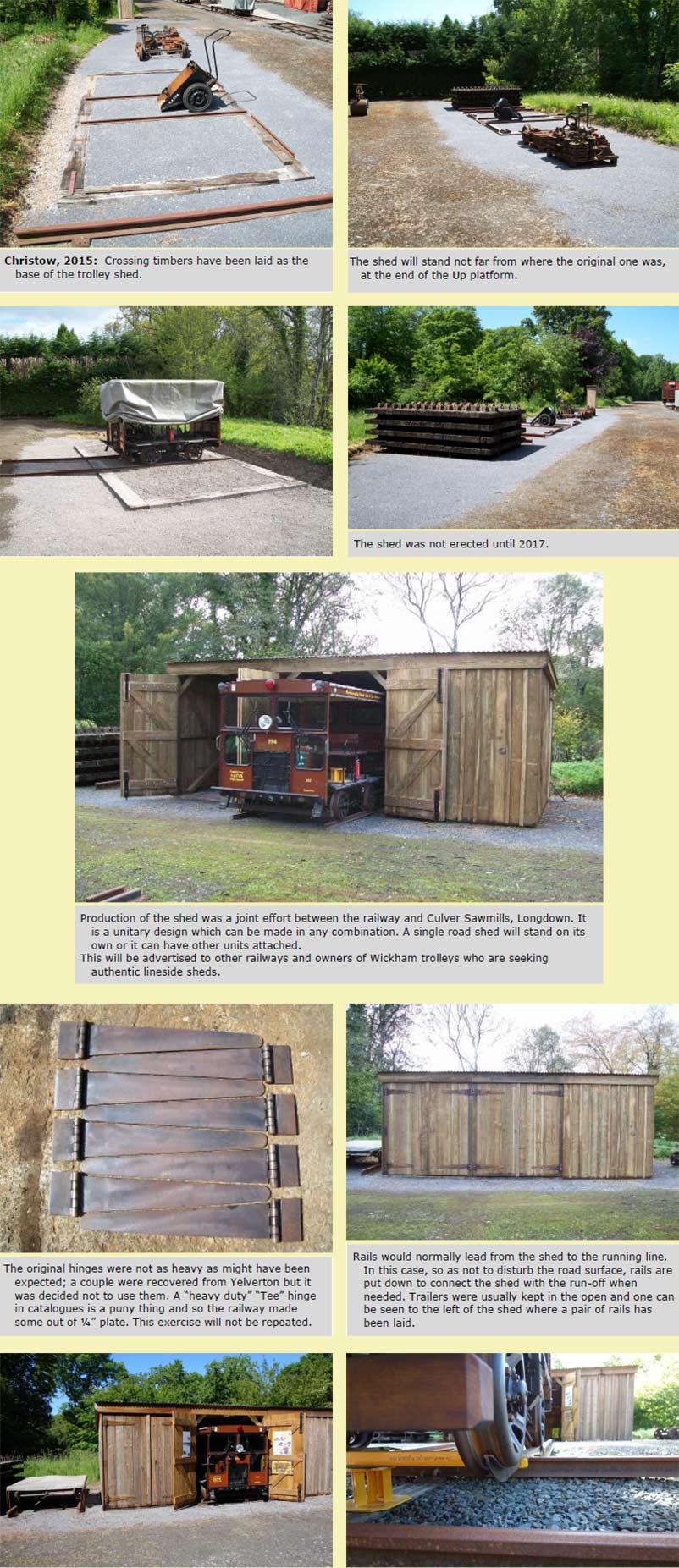

Of all the motor trolley sheds that once stood beside the line, which are glimpsed but never remarked upon in numerous photographs, as far as is known only one remains in the West Country. The three-road shed at Yelverton, abandoned in 1964, was in ruins when photographed in 2012 but enough was left from which to take some basic measurements.

Two door bolts and a bit of cover strip have been used on the railway's recreation, which stands not far from where "The Flying Pig" was shedded beside the Up Main, opposite the signal box.

The original sheds were made from sawn sleepers. The frame members were 5" x 5" and cladding boards were 9" x 1", four being got from a sleeper. The framework of the new shed is 4" x 4" and 4" x 3"; any greater than this would have been a waste of timber and an infringement upon space. The roof pitch is 3½°, perhaps noticeably flatter than the originals' 6°, but the shed will accommodate a later Type 27; most of the older sheds would only have been built for the smaller Type 17s.

When the timber has settled it will be finished in black drab to replicate tar.

Nesting boxes have been made in the front corners. It has already become home to mice, which are chewing anything left on the ground made of plastic.

Shelves will be installed in the stores section and the shed will be the centre of a branch Permanent Way depot.

It is hoped that this building will cause people to dwell upon the mostly unsung work of the old boys who turned out in all weathers to keep the track in good fettle, without which the branch trains, always in the lens, would not have run.

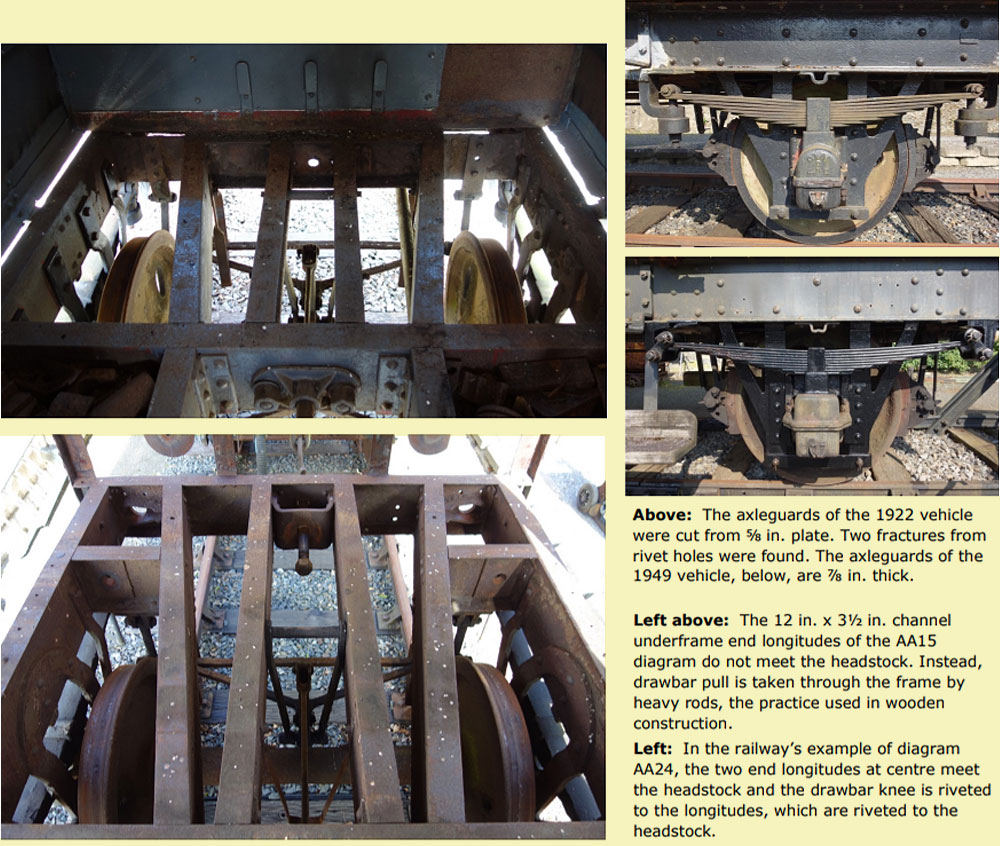

Completed by the railway and Culver Sawmills in January, 2019, was another trolley shed, adapted for use as a Building Department store. It differs from the first one in that it has a 6° roof pitch and diagonal bracing only in the clad "unit." It takes no support from the neighbouring wall. A line of rails was set in the concrete with a view to it being connected to a two-foot layout.

Running-In Boards

The last of the exhibits to be completed for the Pumphouse annex to the main exhibition in the Temporary Booking Office were the running-in boards, on permanent loan to the railway.

The dimensions of the frames were guessed from the few close-up views known, one being the camera pausing on the Downside board on the B.B.C. last-day film. It had been decided that they should be two inches deep but the sawn timber gave 2¼in. so it was left at that, the thinking being that the extra strength would be useful in restraining the badly distorted steel panels; presumably this was caused when the enamel was kilned. The timber is meranti and the finish is Dulux's Ultimate Opaque, a kind of coloured wood stain with a claimed ten year life outdoors. The Christow board was taken to be scanned and the letter colour was found to be a close match to a Dulux shade.

The panels would likely have been captive in their original frames, but the new ones allow their release. If the owner should decide to reclaim the panels, then the frames would be used to make fakes.

The boards are resting on brackets in the Pumphouse and it is hoped to take them back to their proper places for photographing.

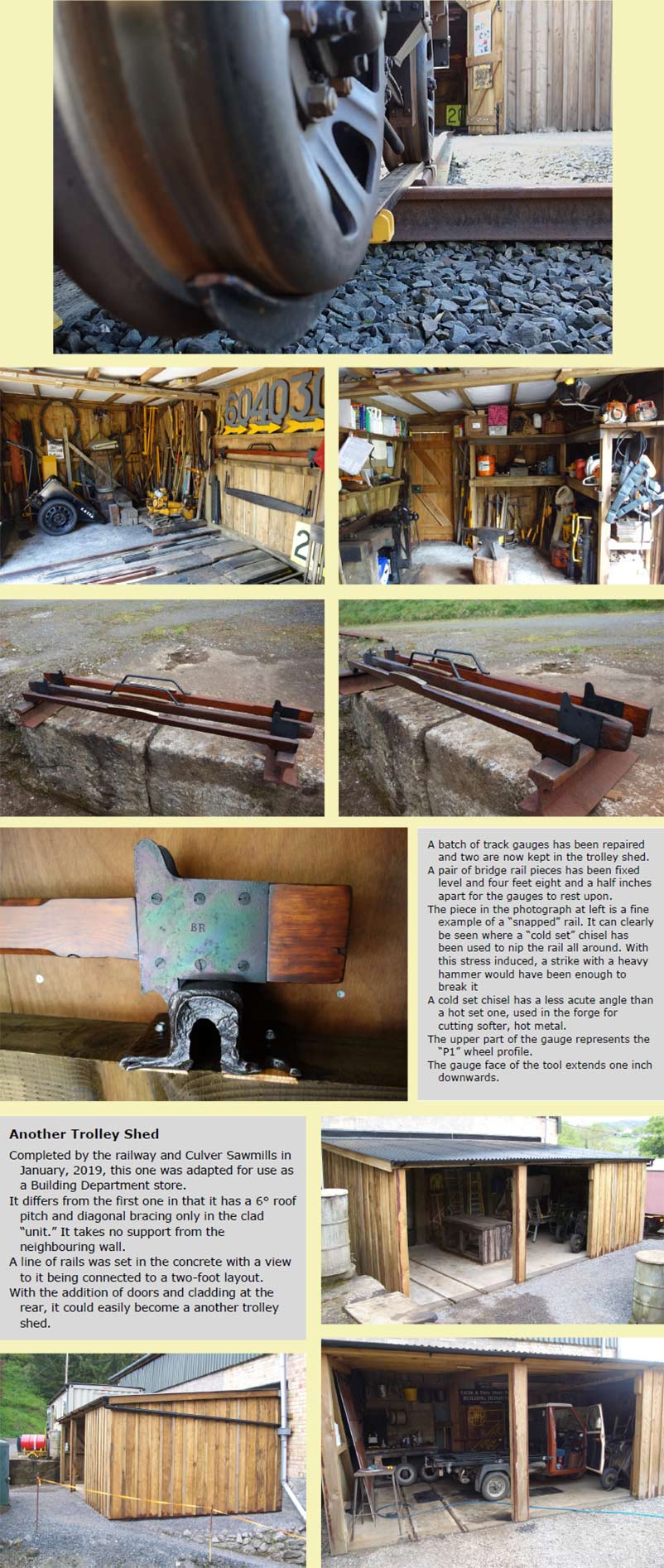

Enough timber has been machined to make another "Christow," and it would not have taken much more to have provided for Ide, the shortest station name in the country.

The boards are mounted on lengths of 70lb./yard double-headed rail, last rolled in the 19th century. Actually, they are made of larch which was passed 18 times through the machine on eight different settings to get the rail profile.

The story of how the running-in boards were saved and how they came to be returned to the Teign Valley:

A clip from the B.B.C. last-day film, which includes a scene shot on the Down platform at Christow, can be seen here.

This item is one of three on the railway's YouTube channel playlist, "B.B.C. Spotlight."

17953

This 1922 vehicle was lying at Llynclys Junction, on the old Cambrian, when it was bought by the new, rail-enthusiast owner of Station House (the former station buildings) at Christow.

Many Great Western brake vans found another purpose after being displaced. Some left the system. This one was bought by the Manchester Ship Canal Railway, which added plating to the verandah end and an underslung shelf.

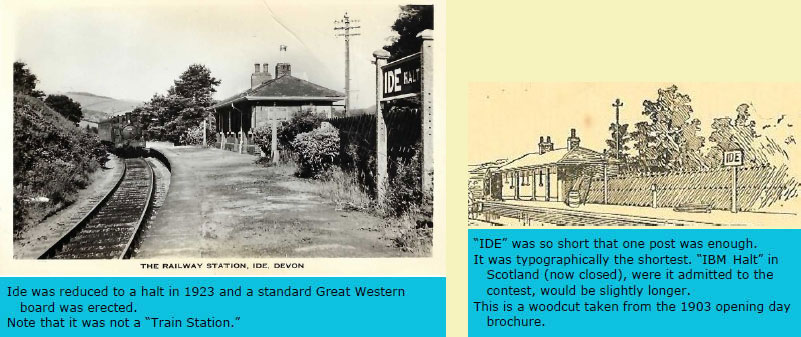

It must have suffered a severe collision at some point. One of the axleboxes had been broken, and the axleguards were bent and fractured, throwing the axle out of alignment.

Work to return the venerable vehicle to something like running condition involved: removing the modifications; fixing the brakes; servicing the axleboxes; straightening and welding the damaged axleguards; straightening, aligning and welding the running board brackets; specifying and fitting new running and step boards; replacing the verandah side plating; making good the grab handles; patching the bodyside plating; taking up the floorboards and stripping the interior; fitting a new floor to the verandah; repositioning the brake column; and fitting a new vacuum branch pipe with setter and gauge. Marks Brothers Roofing Ltd. re-covered the roof using liquid rubber.

This van, built to diagram AA15, appears outwardly the same as the railway’s 1949 vehicle, built 27 years later to diagram AA24. But there are substantial differences beneath the surface. Severe weaknesses in the design, revealed in operation, must have led to strengthening members being added to 17953 and a re-design of later vans.

The removal gang and the railway's fitter relax before the old van is lifted onto its length of line beside the loading dock at Christow.

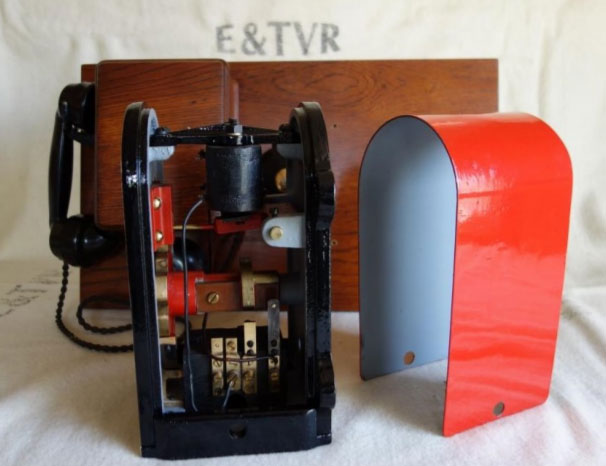

Ganger's Occupation Key Box

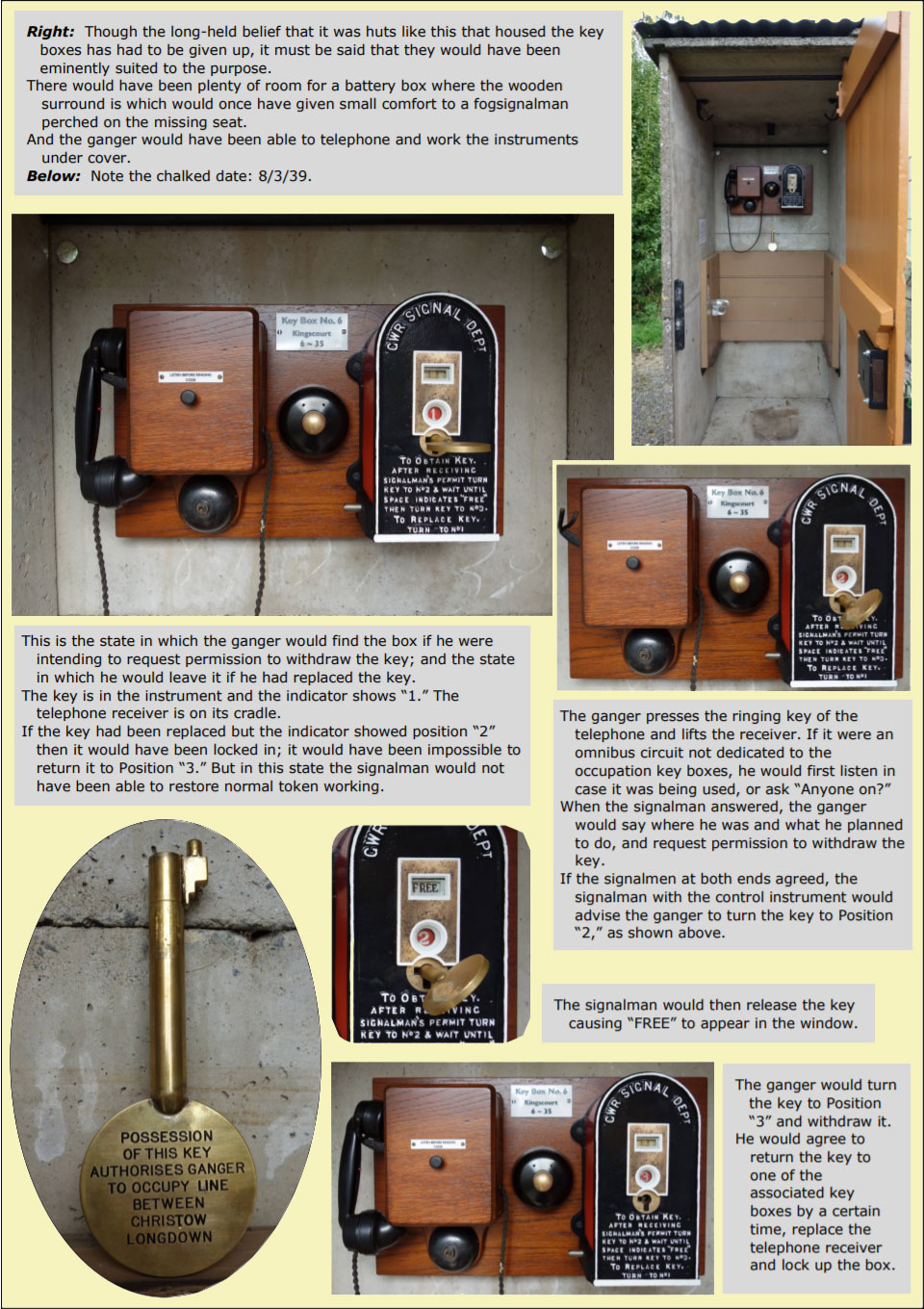

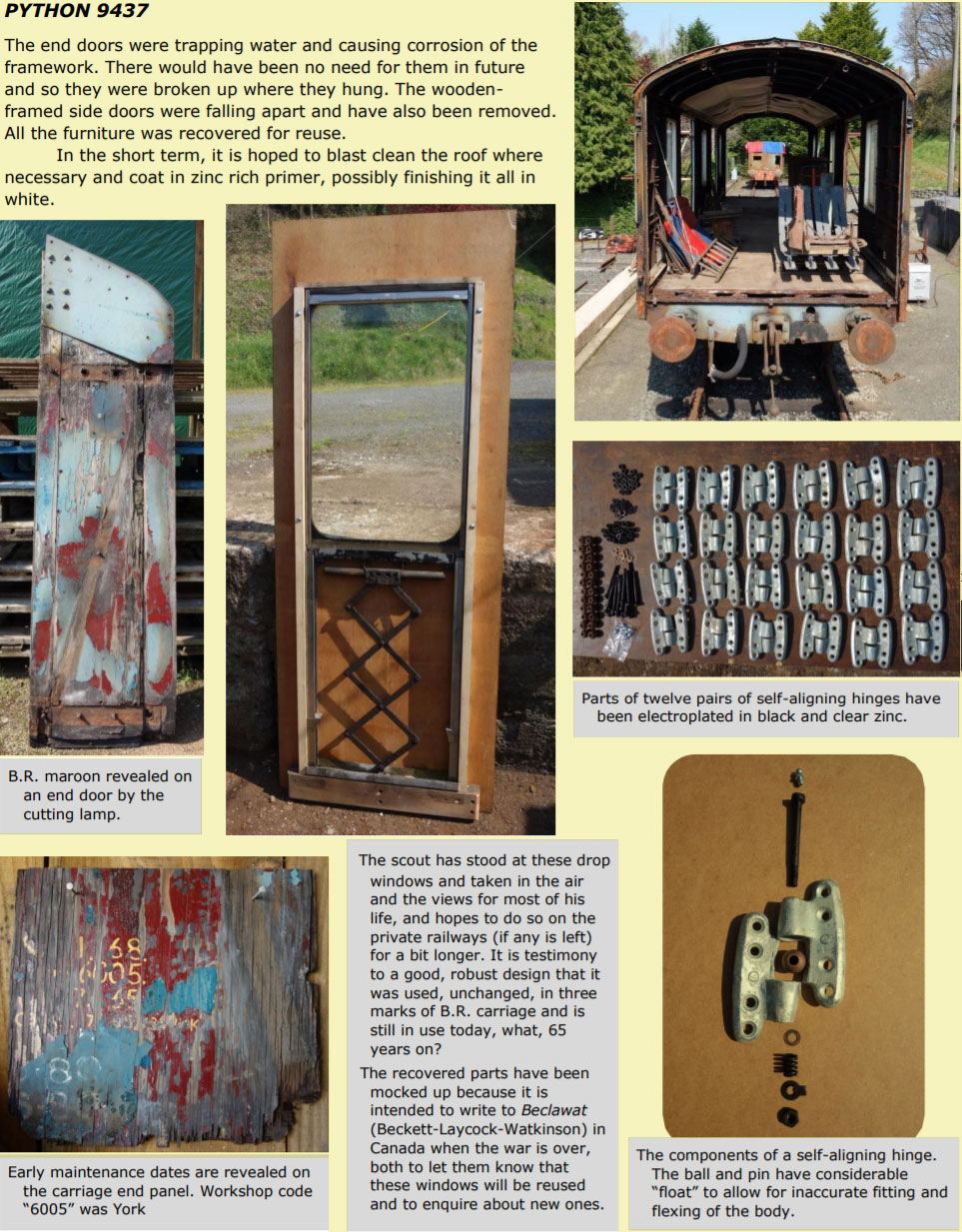

The instrument was given to the railway in good condition and very usefully came with a blank key. The original locking bolt for the cover and electrical connections were missing.

It was completely dismantled. The exterior of the cast iron body and the steel cover were blasted clean and finished in black and signal red. The interior was coated in grey primer. Steel set screws were black-zinc plated. The internal parts painted red were left and the white numbers on red discs were touched in rather than repainted. The brass plate framing the two windows would have been black but it was left unfinished, save for the white lining.

The most demanding task was the white lettering, the smallest of which below the keyhole is very small and in places was difficult to pick out even with the finest brush.

The “A” pattern key was engraved and filled by Stalite Signs only on one face. If it is found that keys were engraved on both faces then it will be done again.

A piece of tropical hardwood was selected for the backboard and studs were fitted to suit the holes in the wall of the fog hut. Although it was subsequently found that instruments were not housed in these huts, the backboard is nevertheless a compact way of displaying the assembly in the exhibition, where it will be kept most of the time.

So that the system may be demonstrated, a means of electrically releasing the occupation key has been incorporated within the assembly.

The “Economic System of Track Maintenance” was introduced by the Great Western in 1901 as a means of giving single line gangs complete protection without the need for handsignalmen.

On lines later equipped with self-propelled trolleys, it became the “Motor Economic” system, appearing as the “Motor Trolley System of Maintenance” in the 1936 General Appendix. The instructions were repeated word for word under the same heading in the B.R.W.R. Regional Appendix issued in 1960.

Latterly, in the Great Western’s Exeter Division, different systems were in use on the branch lines.

The Yeovil, Culm Valley, Kingswear and Brixham branches were not equipped with the occupation key. The Moretonhampstead and Tiverton branches were maintained using the Economic System. The Chard Branch used a “Modified Motor Trolley System.” The Minehead and Barnstaple branches, with their double line sections, used the Motor Trolley System over most of the single lines. The Exe and Teign Valley branches used the Motor Trolley System throughout. The Teign Valley was the only one with a centrally based gang responsible for the whole branch.

The four gangs stationed along the Barnstaple Branch may have had eight trolleys between them. The Teign Valley gang had two: a light inspection car for the ganger and a trolley for the men and their tools, shedded at Christow. The motor trolleys were capable of hauling a trailer loaded with materials.

For an unknown reason, the Motor Trolley System was not used on the Teign Valley’s neighbour, the Moretonhamsptead Branch, which had key boxes in huts along the line, possibly those already in situ.

The installation was much the same, whether motor trolleys were used or not. A group of instruments, key boxes, at roughly one mile intervals between token stations, each with telephonic communication to the signal boxes, had one or more occupation keys which, when withdrawn, would prevent signalmen allowing a train to enter the section.

Before control instruments were introduced, only one key could be withdrawn from a group of key boxes. Control instruments allowed two or more keys to be withdrawn at the same time. The single line token apparatus could not be reactivated until all the keys were returned to the key boxes.

A gang traversing sections would need the freedom to be able to run off the motor trolley at any of the key boxes; if there were another key, it would have to have been in one of the key boxes and this would have reduced the gang’s freedom. Thus, on the Teign Valley, each of the four groups of key boxes had only one key and in normal working they would be found at the start of the day in the three intermediate signal boxes, with two keys at Christow.

Having said this, the two intermediate groups of instruments on the Minehead Branch, on which the Motor Trolley System was adopted, had two keys each.

The two groups of instruments between Heathfield and Moretonhampstead had two keys each, but on this branch the gangs were only using man-propelled trolleys which could be lifted off the line easily at any place. The Bovey and Moretonhampstead gangs would have maintained the line as they had done before the Economic System was installed but with the advantage of not having to send out two men to give protection.

The section between Bovey and Moretonhampstead shared two keys, but with only one key available at a time; Bovey’s length extended just short of Pullabrook Halt.

Were the occupation keys returned to the three signal boxes, Heathfield, Bovey and Moretonhampstead, at the end of each day, or was it the practice to leave keys in the Key Boxes where work was being done and withdraw them from there when continuing the next day?

How did it work?

The system may be best understood by giving a practical example of its use on the Teign Valley Branch.

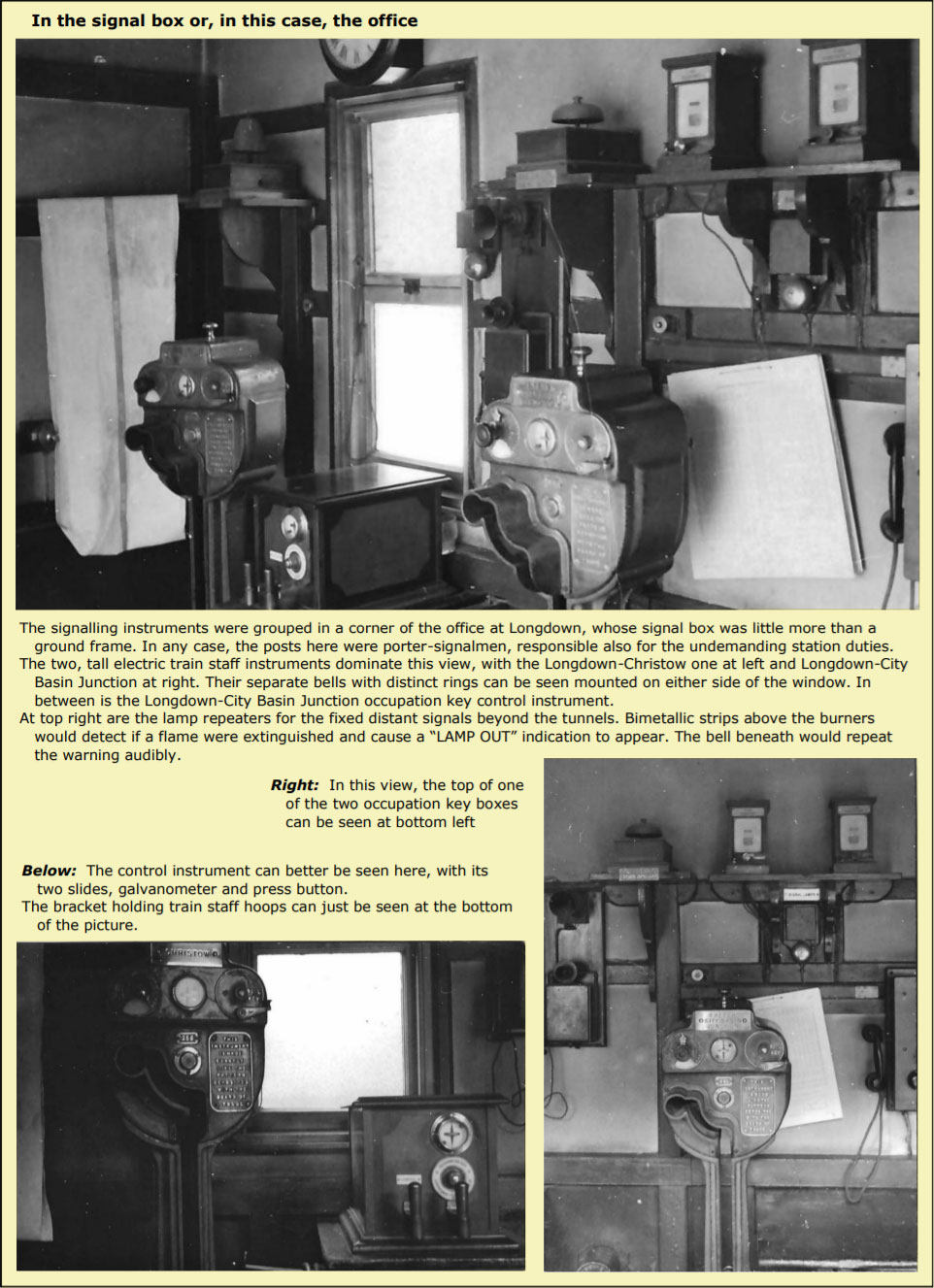

Control instruments were installed at each intermediate signal box. Longdown’s controlled the single line section to City Basin; Trusham’s the section to Heathfield; Christow, where the gang was stationed, had two, for the sections to Longdown and Trusham. A total of 13 key boxes were spaced in sections; eight more were installed in the signal boxes.

When the scribe was in the company of the old boys who could have told him how it was all done, he did not have the knowledge which would have empowered him to ask searching questions; and now he does not recall hearing any mention of the system, whose use must have ceased by the mid 1960s, with the introduction of road-mobile gangs and the closure of so many branches.

And, as well as not so far having been able to identify the form of the ganger’s own trolley, a “Motor Inspection Car,” despite a local elderly resident remembering it, the scribe does not know how the ganger used it for his inspections, one of which every week was done on foot in order to examine the permanent way and works as a whole.

The working instructions included provision for a signalman to withdraw an occupation key and leave it in a locked box for the ganger, if he intended to make his inspection before the box opened in the morning.

As to the use of the gang’s trolley, there must have been a conference between the ganger and the Christow early turn signalman about how best to fit the movements between trains, where the gang was to stop and what work was intended. This would in turn surely have been passed to neighbouring signalmen if necessary and to the late turn men as the day progressed.

Naturally, this would often have been subject to alteration, perhaps caused by a report of failure or the discovery of more urgent work, or by late or out of course running of the train service, but the facility of telephones at each key box would have allowed revised arrangements to be communicated along the line.

If it is imagined that the gang has wheeled the motor trolley out of its shed and is ready to place it and its trailer on the line opposite Christow Signal Box and proceed at first to a site between Kingscourt and Dunsford Halt to work, then the following is what unfolds.

The Christow signalman telephones the Longdown signalman, advises him of the gang’s intentions and obtains agreement for the occupation. The Christow-Longdown control instrument has two slides. The one on the left marked “Control” has three positions. The Christow signalman has withdrawn it from No. 1 to No. 2 position.

The Longdown signalman holding down the bell key on his electric token instrument, just as he would to cause the release of the main staff token, releases the control slide which the Christow signalman then withdraws fully to No. 3 position. This in turn releases the second slide marked “Occupation Key,” which when withdrawn enables the occupation key to be released.

Fixed near the control instrument is one of the five occupation key instruments in the Christow-Longdown section group. The occupation key is locked in it and “1” will show in the window above the key. The signalman or ganger turns the key anti-clockwise so that “2” shows in the window. At this point the signalman presses the button above the occupation key slide and observes an indicator needle deflect. This causes the word “Free” to be displayed in another window of the key instrument. The key is then turned to position “3” and withdrawn.

This may sound convoluted but so would many procedures in a mechanical signal box if described in detail, as has been done here. In practice, this routine would be done in a minute, accompanied by clicks and clacks and short exchanges over the phone, and the sort of chat that men who know each other well engage in while doing their jobs effortlessly, all the while having safety in mind.

Meanwhile, the motor trolley, a Wickham Type 17, has been bumped around on the timbers between the rails by hand, followed by the trailer, which has been coupled and loaded with whatever tools and materials are needed. After carrying out the required checks, a man has cranked the JAP engine into life.

If the ganger is going with his men, he jumps in the trolley with the occupation key and sets off Up the line as a train, complete with tail lamp. If not, he hands the key to the man in charge.

The signalman sets the road but does not clear the signals.

The system allows for two trolleys (“trollies,” in the 1930s publications), with or without trailers, and the Ganger’s inspection trolley to proceed into the section, permissive fashion, provided that the key is not replaced and the occupation given up until all the vehicles are clear of the line. This would have to be the subject of a very clear understanding if the trolleys were being run off at different points.

The heavy construction of the Exeter Railway for the most part dictated where “run-offs”—short tracks at right angles to the main line—could be installed. There was generally not space at the top of an embankment or within a cutting, so run-offs are found where the two meet.

The signalman, after seeing the trolley enter the section, as a final precaution drops a collar on the lever of the starting signal. Through the columns of the Train Register, he writes the times and full details of the possession agreed with the ganger; he will similarly record all other communications and procedures connected with the operation of the Motor Trolley System.

The gang passes the first run-off only ⅝-mile from Christow. It is situated where a lane had been severed by the line’s construction and diverted beneath the railway to Leigh Cross.

It is not far beyond the next run-off, a mile further on, that the gang is to work and the trolley is stopped at the site, where the tools and materials are flung off and the trailer lifted clear of the line.

The motor trolley then returns to Kingscourt where it is run-off using the simple onboard turntable and secured. Beside a telegraph pole nearby is the key box, but the key is held as protection while the men set about their work, perhaps changing a sleeper, oiling fishplates, cleaning the cribs, lifting and lining the road, or any work that would affect the safe passage of trains or for which the men would otherwise need lookout protection.

If the gang were working on fences, or mowing the linesides and were likely to be there for all or most of the day, as soon as the trolley were clear of the line the occupation key would be returned.

In any case, the occupation has to be given up before the next train. The rule states ten minutes (later reduced to five) before the departure of the next train from either end of the section.

The key is inserted and turned clockwise to position “1”. At position “2” the key is mechanically locked in and cannot be returned to “3” without another electrical release. When the key is restored, the ganger or man in charge telephones the signalman at Christow and notifies him that the line is clear. He then presses the plunger until advised by the signalman that the control apparatus has been properly reset.

The signalman returns his control instrument control slide to No. 2 position. If the occupation key has been accepted, the indicator needle will deflect and the signalman can then push the occupation key slide to the No. 1 (normal) position and the control slide to the No. 1 (also normal) position.

If the next train were not waiting, the signalman would immediately withdraw an electric token using the testing arrangement provided for in the signalling regulations. When either this is done or a token withdrawn for the next train, the ganger is informed that the system is in order. It may be that the ganger has to withdraw the key and replace it, again pressing the plunger, for the signalman to be able to reset the control instrument.

Continuing with the practical example, after the work is completed near Kingscourt, the ganger now wants to move to Ide. Trains have passed in both directions while the trolley and trailer have been off-roaded and there is now a path which he had agreed with the Christow signalman to take. Thus, when he telephones from the key box, it takes but little time to obtain the occupation key, allowing the gang to put the motor trolley back on the line.

When this is done, the trolley is driven to the site where the trailer was left and this is promptly rerailed, coupled and loaded.

On severe inclines such as this, it is required that a man ride on the trailer to apply the brake in case the coupling should fail.

Seven or eight minutes later, the little train arrives at Longdown. Here the occupation key is given up, as the instrument in the office at Longdown is the last that will accept it. Another, of a different pattern, needs to be drawn for the section to the main line junction.

As the signalman knows what is intended, he may have initiated the process and be ready to release the Longdown-City Basin key; strictly, to avoid the danger of the wrong key inadvertently being taken forward, he should not withdraw it before the Christow-Longdown key is locked in its instrument.

With the road set and after a short dwell with the customary chatter, the trolley soon disappears into Perridge Tunnel.

And so the working day continues, the diminutive trolleys weaving their furtive movements between the normal trains and seeming at odds with the hugeness and smokiness of the 19th century railway. The trolleys being maintained by the Road Transport Department seems to add to the incongruity.

If the plan had been to work at Longdown, then the trolley would have been admitted to the siding. When this was disconnected in 1956, a run-off was made at the east end of the platform.

Trolleys moving between token stations and not needing to stop, or needing to stop only briefly, would normally carry the electric train staff instead of the occupation key. When running with the train staff, the signalman would ask “Is line clear?” using the bell code, 2-1-2, “Trolley requiring to go into or pass through Tunnel.” In this case, the signals would be worked.

So if a fault, for instance at Chudleigh, needed the gang’s urgent attention, then the trolley could be signalled as a train and would carry the train staff over the Electric Train Staff Block Sections, Longdown-Christow and Christow-Trusham. At Trusham, the gang would proceed with the Trusham-Heathfield occupation key, allowing the trolley to be run off at Key Box No. 12.

It can be seen that a disadvantage of carrying the train staff was that it would have left the occupation keys at the wrong end of the sections for the return, if needed; but of course this would have been thought of beforehand.

Having telephones along the line was useful in the event of failure or obstruction. Guards working regularly over the branch were issued with a key to the cabinets so that they could use the telephones to summon assistance or for any reason to speak to the signalmen at the token stations.

Operations which would interfere with the running of trains, or the line becoming unsafe from any cause, would be afforded the necessary protection by withdrawal of the occupation key.

A booklet, “Single Line Control,” published by The Institution of Railway Signal Engineers, kindly brought to the scribe’s attention by Jonathan Flood, provides a technical explanation of the system.

WORKBOX 001944

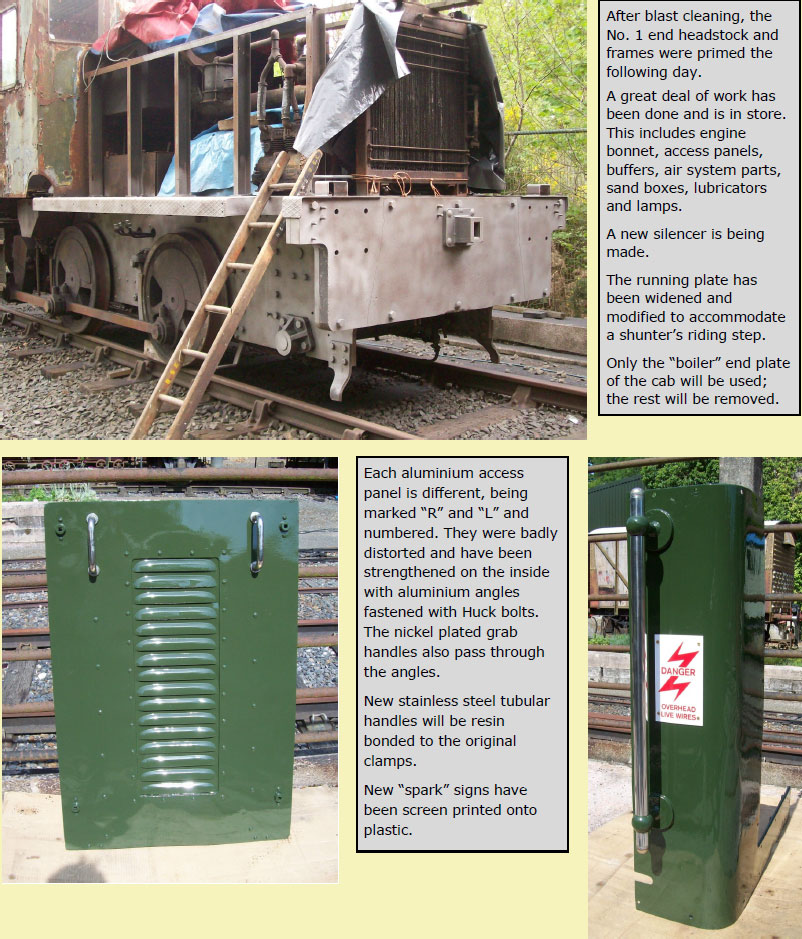

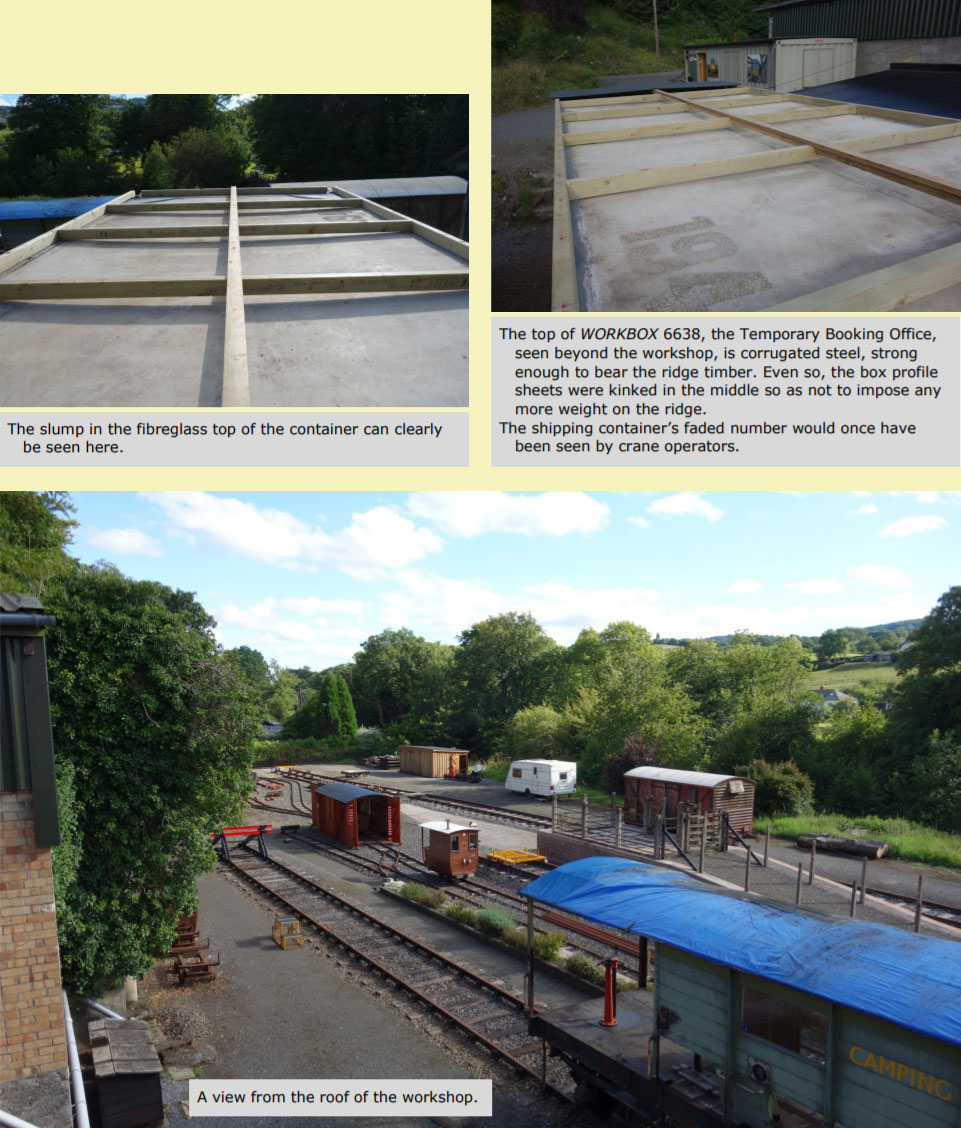

Drops of water landing on the woodworking bench in the winter of 2019 told the Building Department that its temporary workshop, an insulated shipping container, was due for some attention after 20 years’ use.

Water ingress, much of it trapped in the polyurethane foam insulation, had caused the fibreglass top to slump, even before the weather roof was fitted in 2000. Over the years since, the ridge piece, which lifted the box profile sheets one inch at the centre, had sunk and rainwater was puddling in places. The fastenings, direct to the steel frame, were losing their seal.

The roof was raised using 3” x 2” CLS and the ridge was made structural, taking support from the sides.

The box profile was cleaned up and given three coats of black ShieldTec Ultra. Standard roof fastenings were used and overlaps were pop-riveted. The guttering was refixed to the timber.

The body was prepared and coated in Christow Brown, Ultra Brown and black. Water-based AquaTec seems to adhere well to uPVC, allowing the windows to be coated.

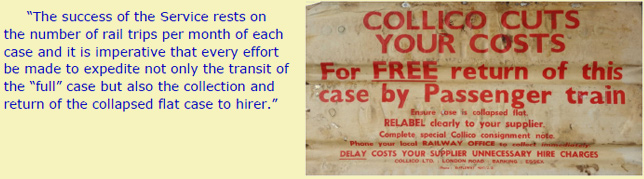

British Railways Collico Service

Although staff at Christow only vaguely remember seeing a few of them in the 1970s, the various forms of collapsible Collico case were once a common sight on platform trolleys and in guard's vans, parcels offices, goods sheds and cartage vehicles.

Extracts from an article, "The Commonsense of Collico," from "Transport Age," a glossy B.R. publication aimed at traders, provides a useful introduction to the concept.

"It is not bulk products but small miscellaneous consignments that cause the big transport problems. Iron ore is simpler to convey than nuts and bolts; grain is easier to move than biscuits. The reason is clear. Bulk buyers are comparatively few in number and buy in large quantities. Buyers of general merchandise number hundreds of thousands and the packages come in all shapes and sizes. One method by which the railways have rationalized much of this amorphous traffic is a triumph of commonsense over complication.

"Commonsense suggested that if this multiplicity of consignments could be organized into a limited range of standard containers, it would be possible to handle, control, transport and safeguard the goods with advantage to producers, consumers and the rail carrier. British Railways saw these possibilities in the Collico Service, and since they adopted it in 1956 a growing list of well-known and enthusiastic users has endorsed their judgment. Collico provides industry with something it has always needed and never before possessed; a standard and widely-applicable packing case, durable, protective, easy to pack and handle, and eliminating completely the problems of recoverable or expendable empties. In addition, Collico users have a two-fold service; from Collico Ltd as suppliers and British Railways as carriers."

"Goods suitable for Collico cover the entire span of manufacturing industry and include engineering components, motor-car and domestic equipment parts, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, clothing, cutlery, foodstuffs, precision instruments, paper and print, china and glass. The aluminium case is the general-purpose container. Steel is used for heavy goods such as ball bearings. Clothing manufacturers prefer alloy and plywood; Collico supply a case fitted with hangers to carry garments without crushing from tailor to shop. Cases can be supplied with special fittings or features such as holes drilled in the base for anchoring engineering components, or rings, straps and foam rubber mats where any extra rigidity and cushioning are required."

"The Collico idea originated on the Continent, and the cases are manufactured by the British company under licence to the German patentees."

Traders hired the cases they needed from Collico and the hire charge, under an arrangement with B.R., included the carriage of the tare weight. Empty cases were therefore returned to traders' premises free of charge; or, if a return load were agreed, a charge would only be raised for the net weight.

To justify the hire charge, traders naturally wanted to see the greatest possible number of consignments carried by each case. The 1963 B.R. handbook, whose cover is pictured in the gallery below, under "Necessity for Speedy Transits," states:

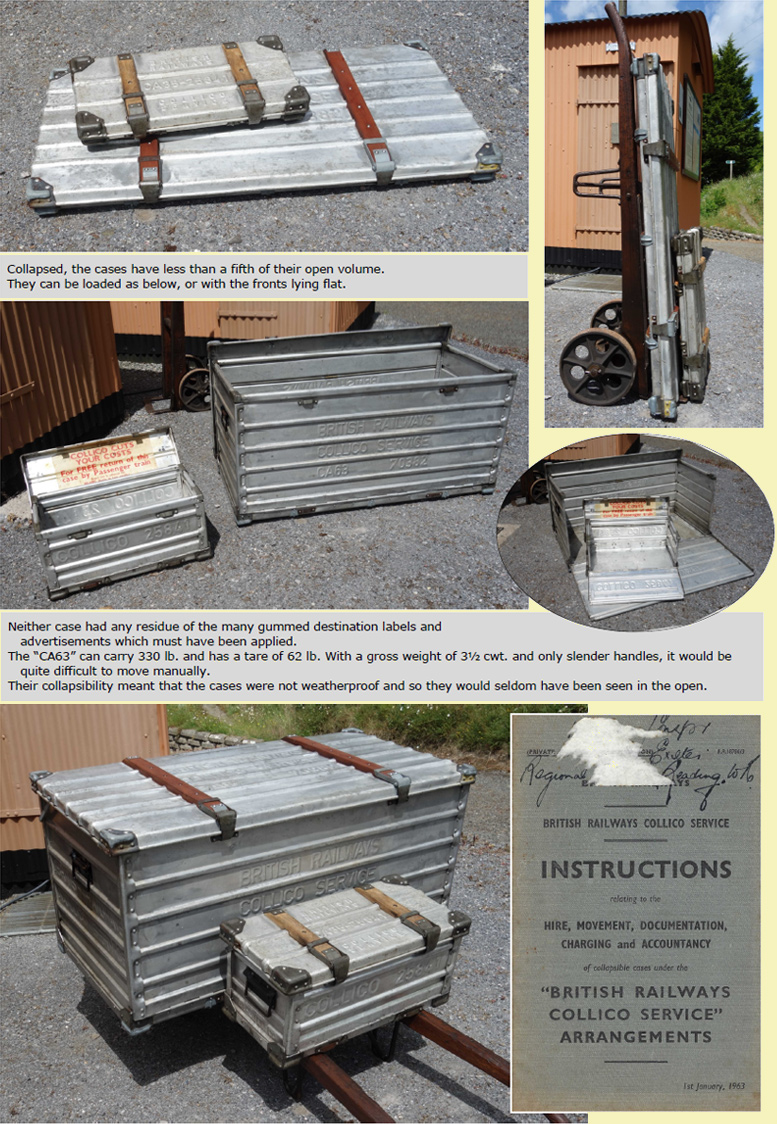

Standard cases were supplied in 18 types and sizes, including the "Hanging Wardrobe" mentioned in the article above. The sizes ranged from 18½" x 9½" x 9½" to 66" x 32" x 32" internally. The serially-numbered cases were allocated to traders and would have been sent from a Collico depot in the first instance. These would have been replaced free of charge if worn out or damaged.

The survivors at Christow are one of the smallest, a "C35," measuring internally 24" x 12" x 12", and one of the largest, a "CA63," 50" x 24" x 24". The repair of No. 70382 was started on 27th December, 1989, but little was done. When work was restarted in earnest in January, 2022, No. 25841, acquired later, was added to the "Small Work" Detail. After extensive repairs to the large one, but only minor repairs to the small one, they were outshopped in February. This most prolonged "Small Work" was costed at £2,006.13, with 3¾ hours at the 1989 workshop hourly rate of £4.83 (it is now £21.80).

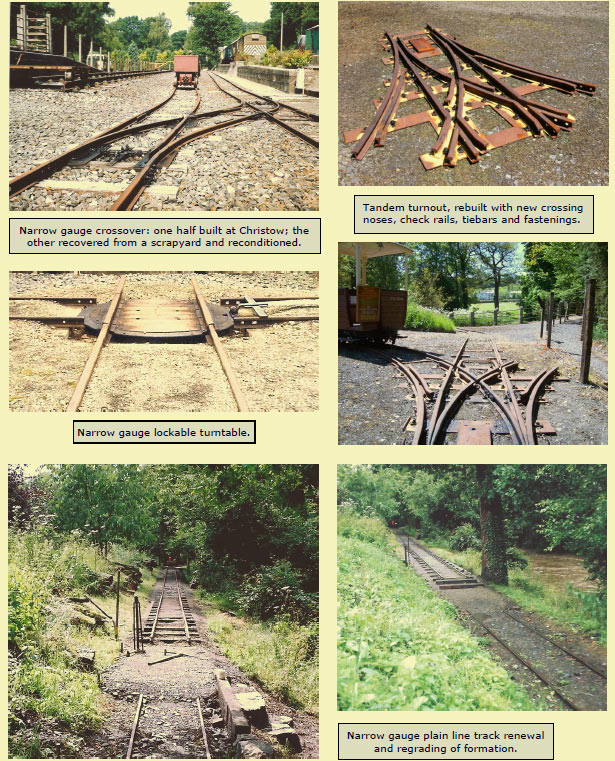

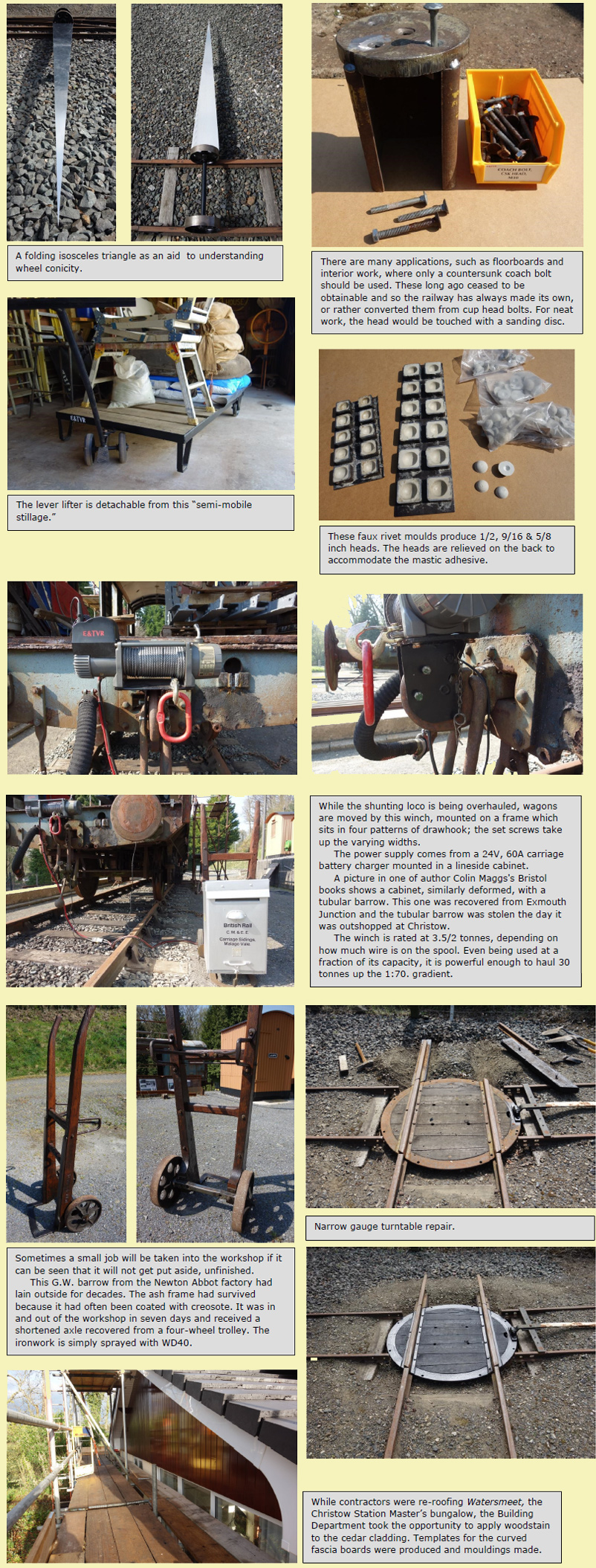

Narrow Gauge Turntable

Though looking as if it could have been supplied by Hudson, the principal component of the two-foot turntable that was made and installed in 1998 actually began life as part of a lorry trailer.

This type of trailer, which is rarely seen now, depended upon a ball bearing turntable ring. Drawing forces, pounding from the road and the weight of loads put great strain on the turntable. Even running light, leaf springs would make the body bounce. When the turntables reached the limit of wear, they were replaced.

The railway was given one of these worn out parts and promptly gave it a new, less demanding purpose. It is only a pity that more had not been obtained when they were being discarded; such parts today cost well over £1,000.

At intervals, the grease gun had been applied to the four nipples but it was felt that, after 24 years on the ground, the table should be taken apart. Surprisingly, the race was still greased and none of the balls had rusted. The bottom ring had become very rusted on the outside and so this was needled and brushed and given two coats of bituminous paint.

The bridge rails originally were welded to the upper ring and the boards were secured to the rails, making the very heavy assembly difficult to handle. As the boards effectively located the rails, it was decided to cut the welds and rely only on two screws to hold down the assembly.

With new fastenings and all parts repainted, the table was returned to its place within five days.

WORKBOX 6638

The 24 ft. x 9 ft. secure site cabin was bought from Wernick Hire Ltd. in December, 2009, and delivered in April, 2010, after space was made for it at Christow.

Wernick spray-painted the cabin "Camouflage Beige." This was an effective colour: several people entering the yard said that they hadn't noticed the new arrival.

As soon as it came, thought was given to some sort of detachable shelter. Nothing was done until late 2021, when the drawing office came up with a simple design. Square section steels which fitted within the corrugations of the box profile roof sheets would be a snug fit between the ridge and the cant rail; they would then protrude and be bent so that the shelter would drain into the existing gutter. Three sheets were ordered; when a perfect "cover sheet" was supplied as well, this was used to make the shelter 13 ft. long.

All the work on the shelter was done during the mild winter. It took ten times longer than it should have done because Cladco in Okehampton, the firm that supplied the sheets, was found not to be rolling to specification. Box profile can be squeezed a little but the ¾-inch excess on each sheet was far too much; the design required the sheets to match the existing and be at rest.

Areas beneath the shelter that needed blast cleaning, filling and priming were done before it was fitted.

The cabin originally had been powder coated. Numerous further coats of paint had been applied with little or no preparation. It was soon found that peeling paint was best scraped off and then the edges not feathered, as would normally be done. Lifting paint had trapped moisture and in some places the 2mm corrugated sides had rusted through. After more filling and priming, the box was given two coats of Christow Brown, with the door and shutters finished in Ultra Brown. The aluminium windows were finished in white.

Aquatec's ShieldTec Ultra eggshell paint makes none of the demands of the coach finish applied to the narrow gauge saloon, where every brush stroke is made with care. The water-based paint does not run or flow; it is heavily pigmented and dries quickly—too quickly in the warm. It can usually be overcoated within the hour and is soon hard.

The internal door and frame were revarnished on the outside. An enlarged mat well was made and provided with a commercial-grade mat. The seat outside was stained and painted.

Work was completed on 17th May.

MUSSEL 4768

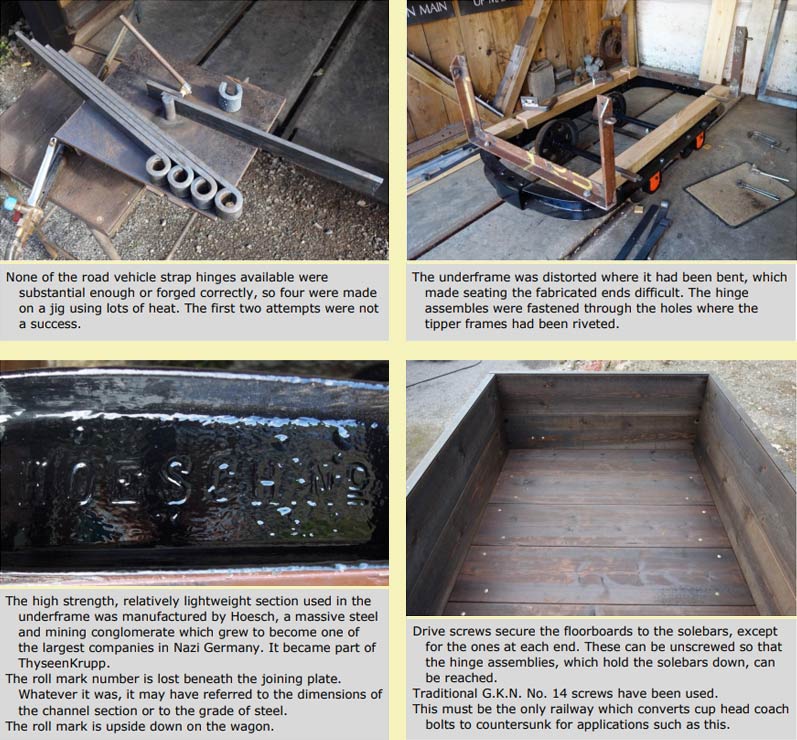

The Open Inspection/Observation Saloon was built at Christow in 1995, using a former side tipper underframe of unknown age recovered from the former Yeoford Sawmills.

It was not completed in time for the June Open Day so some old boards were fitted to the steel body to allow rides to be given.

Before continuing with the woodwork, it was decided to strengthen the body as it had shown itself to be insufficiently braced. The vehicle was finally outshopped in August, 1995.

A parking brake was fitted in 1997. With the extension of the running line a few years later, this brake was needed on the move but, due to its design, was always somewhat unsatisfactory; several modifications were made over the years.

The greatest improvement was made in 2000 when the wheelsets were turned and "budget" ball bearings fitted. The axleboxes, which had contained plain, uncaged roller bearings, were opened out to admit the new bearings. The saloon was thenceforth an excellent demonstrator of the free-running nature of railway vehicles. At the same time, the axles, which had been cut and crudely regauged using angle irons, were joined using machined sleeves. A gear was fitted to one axle to allow conversion of the saloon to "electromotive."

Standard gauge wagons were usually given a General Repair after around 12 years, with an Intermediate after six. A General Repair was a complete overhaul and often involved dismantling the wagon. After 26 years, 4768 was brought into the workshop for, by any standard, a long overdue General.

A few assemblies did not warrant taking apart but otherwise every last piece was removed for some kind of attention.

For a long time, the saloon had carried beneath the seats the varnished wooden battery boxes from a Harbilt pedestrian float; the motor and control gear had been kept in store. In 2021, it was finally decided to give up the idea of converting the saloon to battery electric propulsion.

The principal fault with the brake design was the connecting chain used, a simple device which allowed the brake to be applied at each end independently. Adjustable rods were substituted, free to slide when their opposite was used, and the whole rigging was gone over in an effort to get the parts of a less than perfect design to work as best they could.

It was intended to send away a lot of steelwork for blasting and finishing but the excellent facility at Crediton had been lost before the plague began and the opening of its replacement at Cheriton Bishop was continually delayed. After a long wait, the wheelsets (along with a pair for WHELK 5210) were taken to the same place for turning to allow fitting of "RMS9" Imperial deep-groove ball bearings, not Skefco but not "budget."

A misunderstanding led to 4768's sets being returned with the journals pared off. The ends of the journals had borne against the axleboxes and taken side thrust. Sleeves were used to close the gap and transfer side thrust to the ball bearings. As these are rubber sealed, the axleboxes will now require no lubrication. Time will tell whether this arrangement is durable.

The floorboards at each end had rotted. These have been replaced with balau grooved decking which have been given a rise in the middle, reminiscent of 1930s Underground stock. A hatch has been installed beneath the seats, partly to give easier access to the brake rigging and partly to allow budding engineers to observe the behaviour of the wheels.

The bottom wall boards at each end needed replacing. The exterior faces of the other boards were stripped and the knots drilled and plugged. Coach bolts with exterior nuts have been replaced by countersunk screws and joint connector nuts, making the bodysides look less cluttered.

To stiffen the bodyframe further, cant rails have been welded in. New vertical handles connect the cant rails with the arm rests at the centres. Ready-made "C" scrolls have been attached to add some tramcar gaiety.

A remote-controlled motorized centrifugal bell had been fitted but it had only been wired temporarily. A battery box with an isolation switch has now been installed. Batteries supply the 12-volt radio receiver and the 24-volt "train supply." Sockets obtained from Romania allow use of an L.E.D. tail lamp or for the batteries to be charged. The American railroad crossing sound of the 24-volt bell was achieved by feeding it 12 volts and removing two of its four clappers.

The p.v.c. roof "canvas" would have been cheap to replace but it was good enough to be put back. It has been finished experimentally with white masonry paint.

In the event, nothing was sent away for blasting. The framework where the floorboards had been resting and a few other spots were blast cleaned in the workshop.

The opportunity was taken to put all the parts on the scales and it was found that the saloon weighs over 9 cwt. With a full load of passengers, the gross could be well over three quarters of a ton.

There was one absurdity before; now there are three, at least. It will be left to visitors to decide what they are.

The saloon has been renamed "Jasmine," after the favourite adopted niece of one of the artisans at Christow.

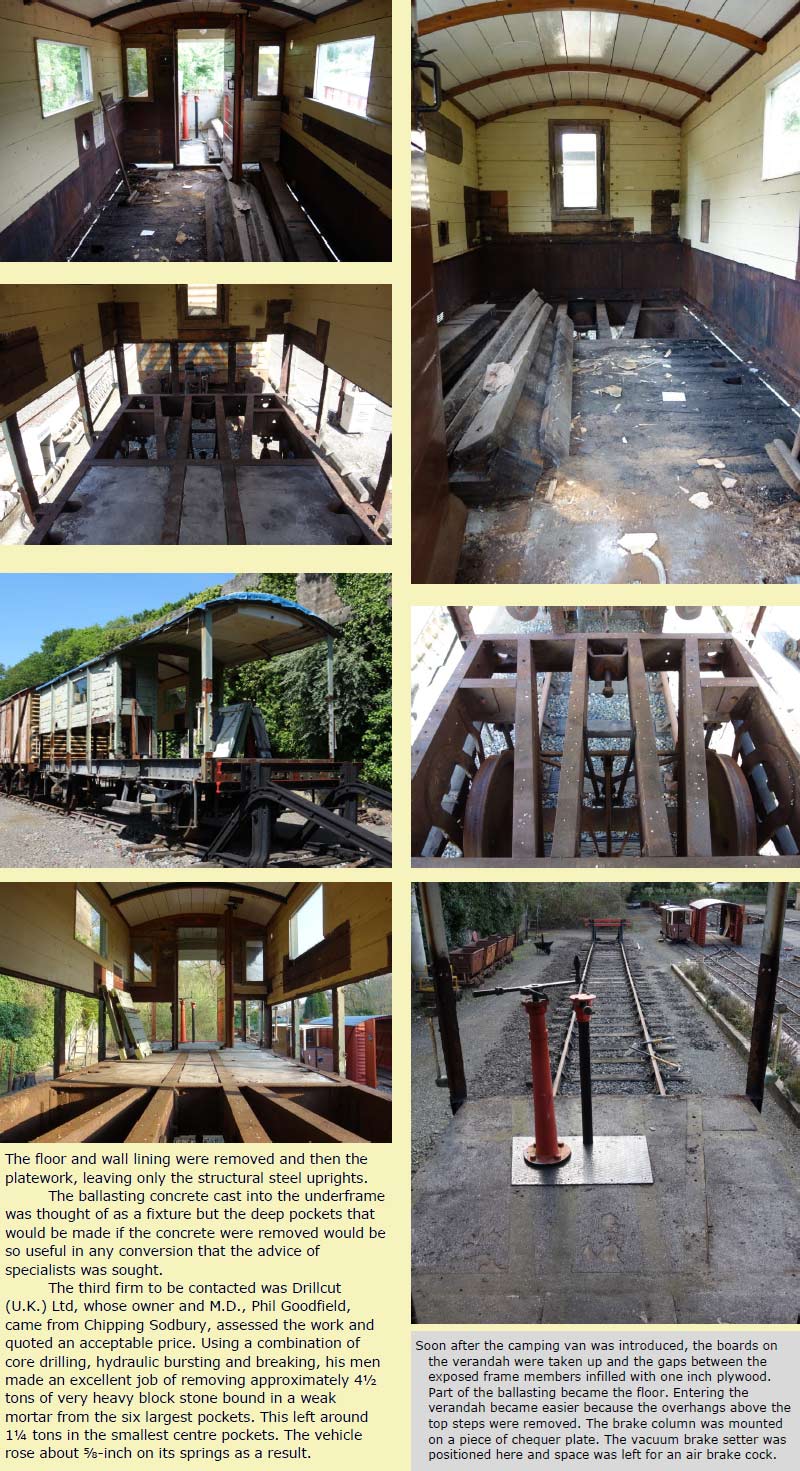

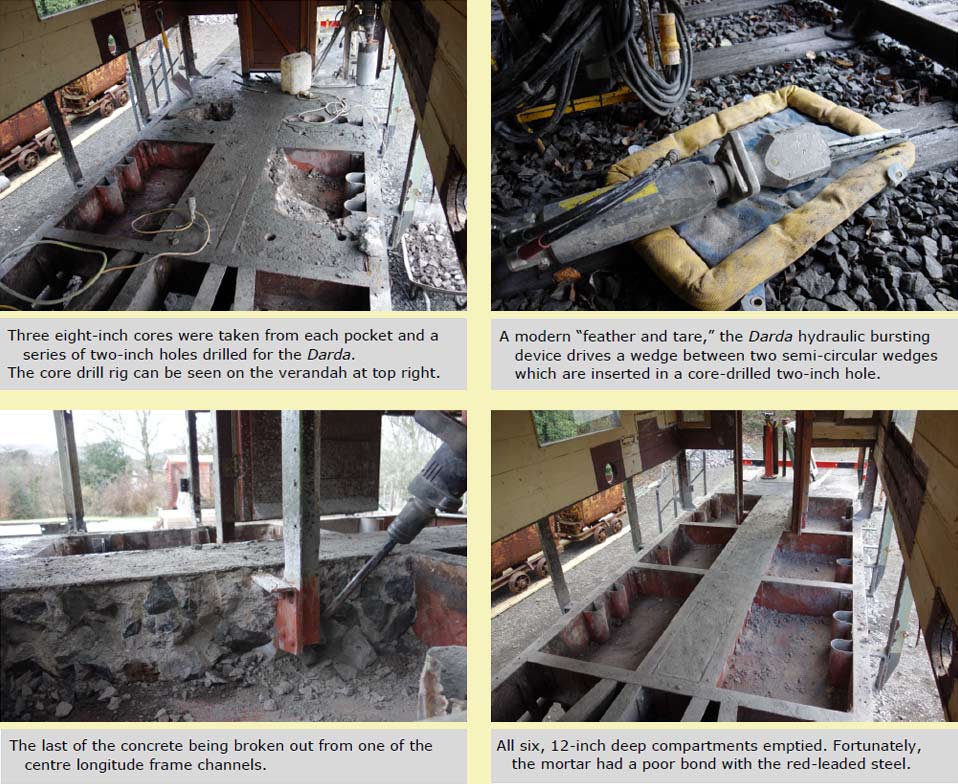

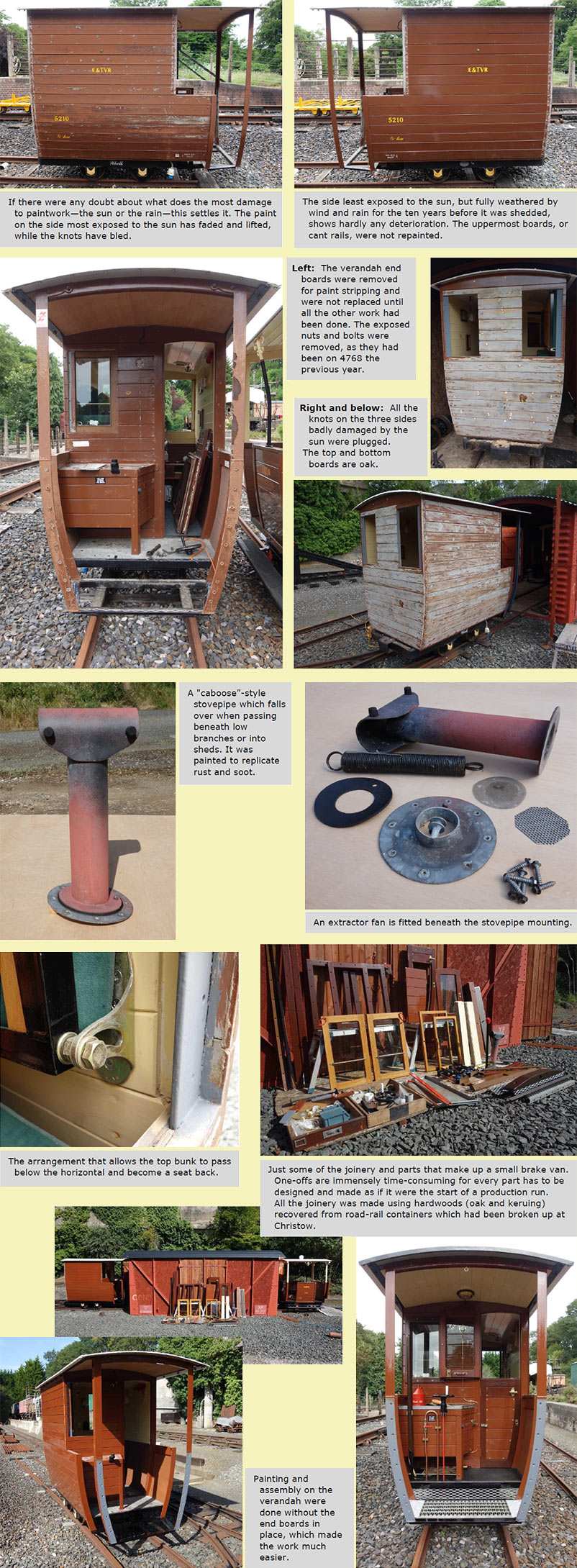

TOAD 35410

The railway's B.R.-built G.W. brake van was in use as holiday accommodation very soon after it came to Christow and was withdrawn in 2019 after 21 years' service, during which it gave pleasure to many people from all walks of life; some from nearby, some from all corners of Britain and some from faraway lands.

It was always the intention to convert it to a staff living van after it ceased to be used for camping, although it has still not been decided what form it will take.

Most of the rolled steel sections are no longer available, even in metric equivalents, and so it was important, if they were to be saved, to strip them of the platework which was causing corrosion.

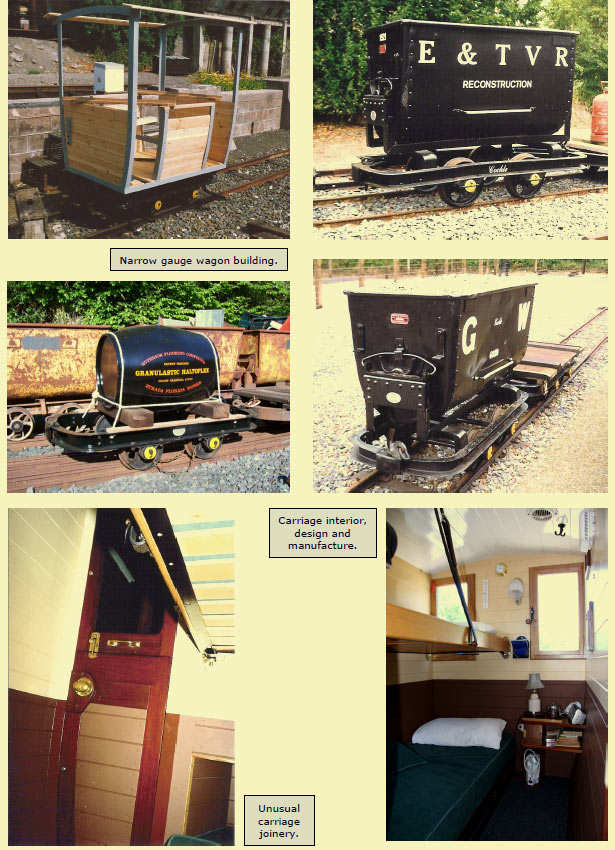

MINKs 78642 & 78651

Both 12-ton covered wagons are long overdue for bodywork repairs. A major part of this will be the production of four pairs of doors. These will be to a slightly modified design, with wider stiles to allow the pairs of plywood panels to be got from one sheet of 8' x 4'.

It is essential, before hanging new doors, that all the work surrounding them is completed.

A large, complicated wooden moulding is fixed above each pair of doors. This acts as a jamb, accepts the bolt and carries a rubber weather flap. When the roof canvases were renewed in 1995, a piece of heavy PVC was tucked under the roof and also acted as the flap. Over time, rain got in and was trapped. Three of the mouldings have been repaired; the other was too rotten. Fortunately, a spare had been kept, recovered from grounded van 785259.

The roof "canvas," actually two pieces of PVC welded together, was found to be in good condition on both vans. The ⅜ in. ply-wood roof was originally one piece, obviously made specially in quantity for Pressed Steel. In 1995, four sheets of 10' x 5' were used to renew each roof. The joint along the top was made using pieces of the same ply and countersunk coach bolts. Eventually, a ridge developed and the joint pieces became bowed.

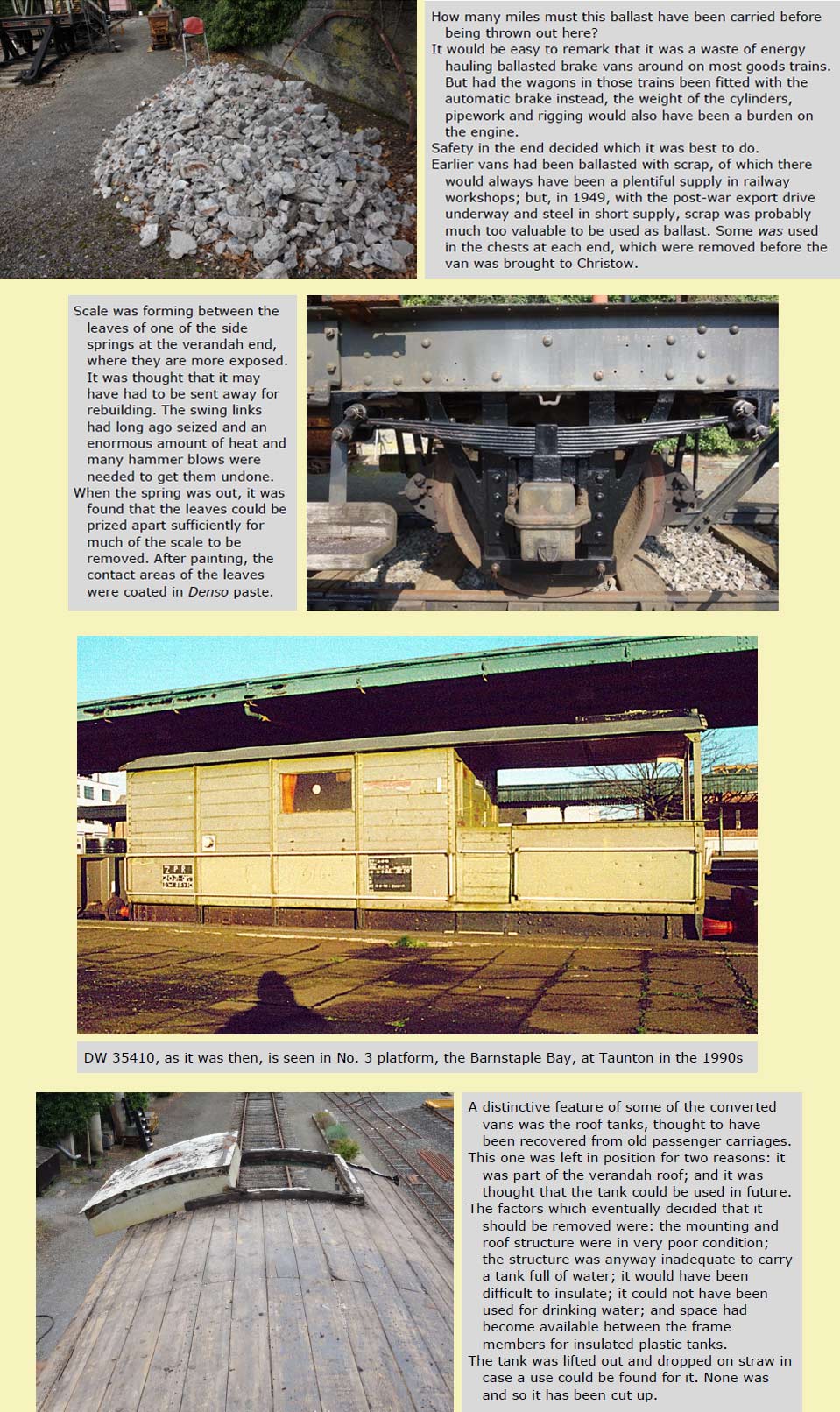

Starting with 78651, the angles at each end were removed and the roof fastenings on one side were cut. The canvas was rolled back beyond the centre so as to reach the joint. This work was done in October and November, 2022, which proved difficult as the plywood had to be kept dry and the canvas could easily have torn if caught by the wind. The centre jointing pieces were removed and replacements made in ⅝-in. ply, using the originals as patterns.

While it was accessible, and to avoid disturbing it again, the area all the way around the roof of each van was prepared and finished in brown enamel. The door frame members were prepared and primed.

After the ridge was flattened, the canvas was secured. Aqua Tec's ShieldTec Ultra was found to remain tacky when applied to PVC and so two coats of masonry paint were applied, followed by two coats of white ShieldTec. This was done in very brief gaps between rain or dew.

In 1995, no rain strips were fitted to direct water away from the door openings, as the fixing of these is always a weakness. In 2023, a gutter was fitted to the moulding, oversailing the new rubber seals below. These were made from galvanized, 60 x 30mm box sections which were cut down their length to make two gutters each. Chutes were going to be fitted at each end of all four gutters but only one pair has been fitted; it may be that they are not needed.

With 78642, it was decided not to release the canvas. Instead, the centre was weighted and the nuts securing the joint boards were carefully undone. The boards were replaced as before. The work was done in May, 2023, when the weather was much kinder.

One of the angle iron trimmers on each van was badly wasted and so spares from 785259 were substituted. On 78651, the angles were set on butyl rubber strips and secured with stainless steel screws. On 78642, non-setting bedding sealant was used, as in 1995.

Telephone Cabinets

These were recovered from St. David's Station when Multiple Aspect Signalling was installed around 1985.

A telephone, usually on a single circuit, was fitted in the upper compartment, behind the drop-down door. Beneath was a dry cell battery compartment with a loose door secured by a bolt.

One of the cabinets must have stood on the Up platform for it had contained two plungers with labels: "Train ready to start," "No. 5" and "No. 6." These would have been connected to Middle Box and would have told the signalman, by means of a bell or indicator, that station work was complete.

Diagonal hatching indicated that one cabinet housed a signal post telephone and gave direct communication with the signalman. A black "St. Andrew's Cross" applied to the door indicated the presence of a telephone (or plunger), other than one at a signal post, giving communication with the signalman.

The cabinets were often used to house an omnibus circuit telephone when they were needed on the lineside, away from buildings.

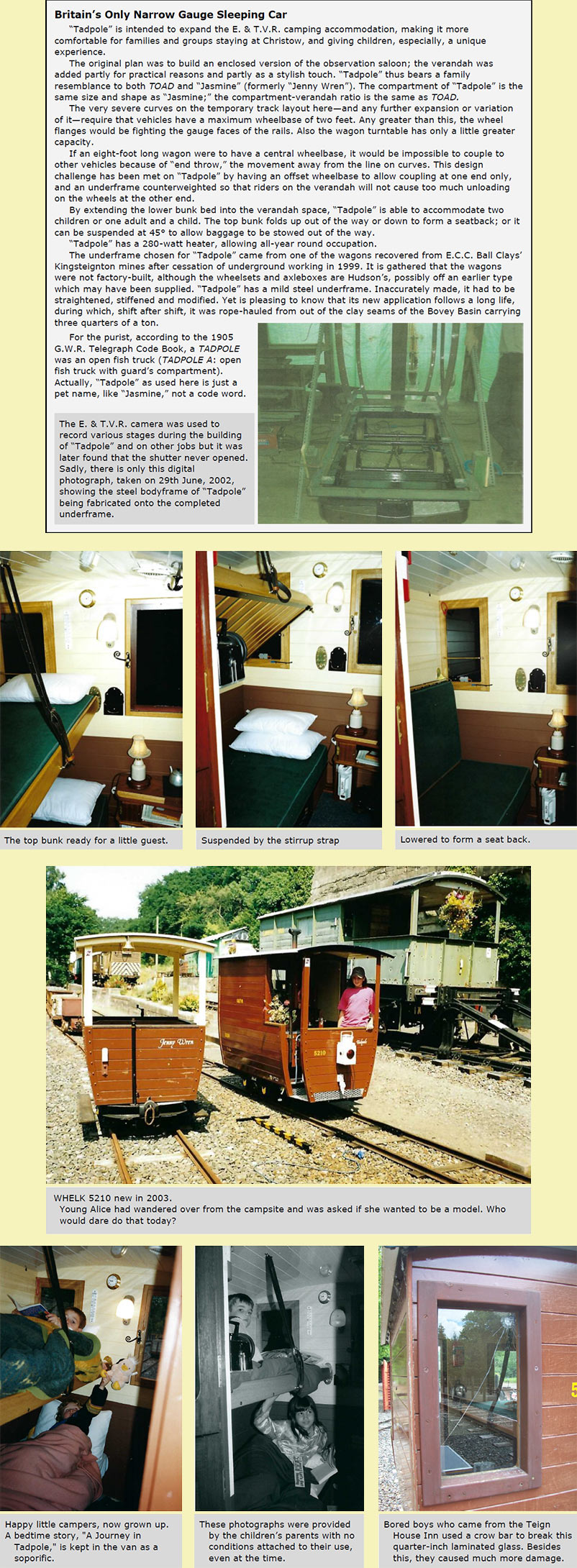

WHELK 5210

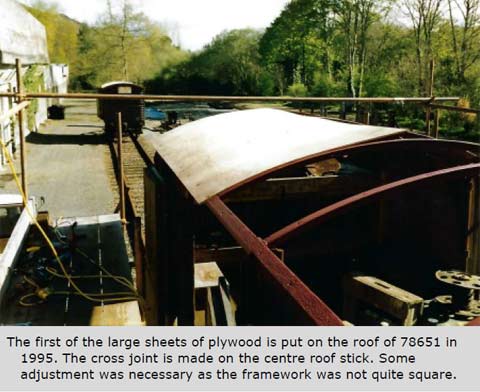

The diminutive brake van was completed in 2003. Like all wooden-bodied vehicles, this one should have been kept in a shed when not in use or on show. By the time the shed was built in June, 2014, the van's paintwork which was most exposed to the sun had deteriorated badly.

General repair involved an exterior repaint, replacing the wheelsets and some minor modifications.

Countersunk screws and joint connector nuts were used to fasten the verandah end boards. A conforming R.C.D. was fitted and the 25V inlet, which had never been connected, went towards making a jumper lead to allow the batteries on the observation saloon to be charged from the brake van.

A fake air brake pipe was fitted to the headstock and a dummy air receiver, made from an old expansion vessel, was fitted beneath the ballast compartment.

The brake van was outshopped in September, 2023.

SHRIMPs 3422 & 3425

Both wagons were taken apart, repaired, cleaned and painted in the standard three coats of chassis black. Wheelsets and axleboxes were replaced. Markings and plates were applied.

SHRIMP 3425 took 32 hours and was completed in July, 2022. Work on 3422 was done while the paint was drying on WHELK 5210. It took 26½ hours over 12 days and was completed in September, 2023.

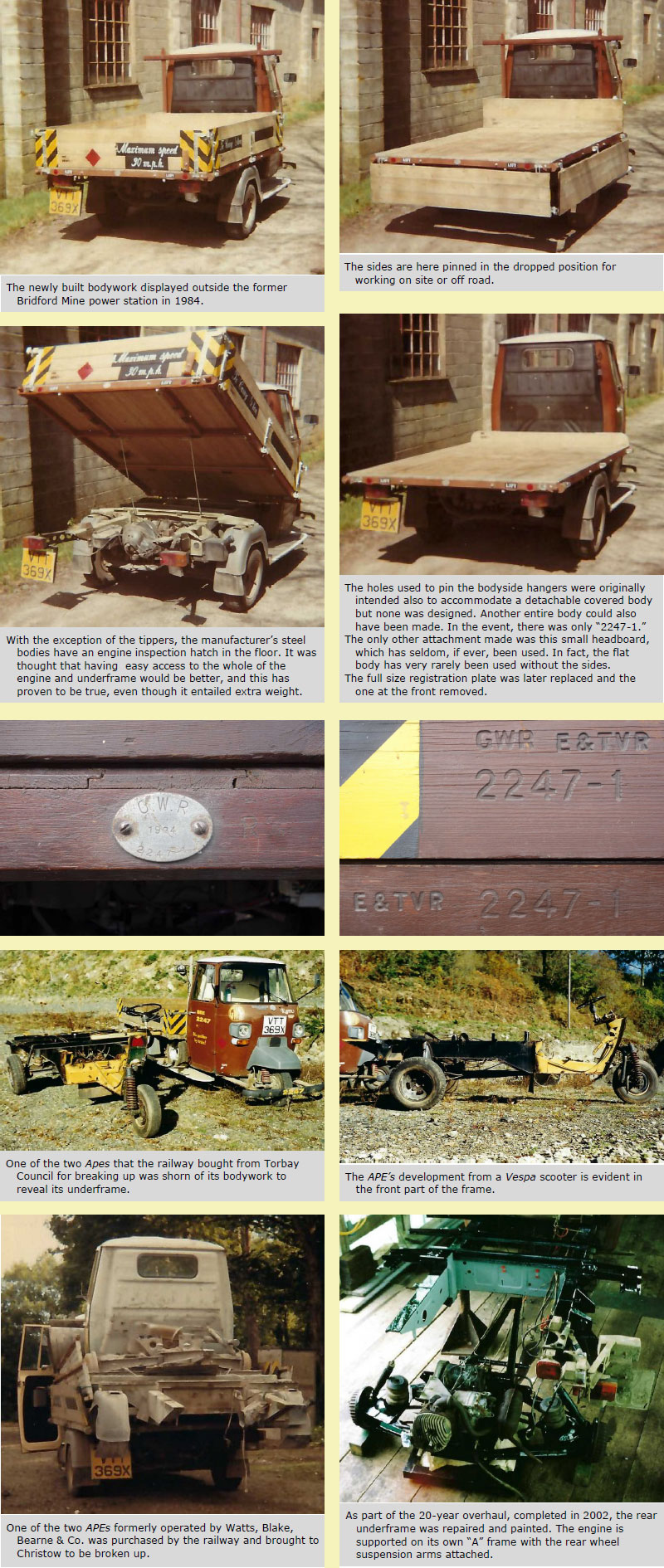

BEE 2247

With the Piaggio Ape TM out of production, the Road Transport Department had started to concern itself with what might replace, or be a standby for, BEE 2309, if it became very unwell, or worse.

More out of curiosity than genuine interest or enthusiasm, various small electric vehicles were studied on paper, including the new class of "Cargobike." These bikes have huge carrying capacity but prices seem very high for what is on offer. In any case, the railway is uneasy about the sourcing and disposal of lithium, the key constituent of most traction batteries.

Staring at the department was BEE 2247, confined to shed since 2007, but with a stock of parts, including spare engines, to make possible an overhaul; this had always been intended but somehow became overlooked.

The overhaul was commenced with servicing the hubs and cables in March, 2024, and was finished at the end of May. The engine was replaced with a low mileage unit, thought to be the one from the Ape used by Exeter City Council in Exwick Cemetery. Some cables and the clutch were replaced with reconditioned parts. Brake hoses, elastic couplings, oil tank, air filter, dynastarter belt and the battery were also replaced. The cost of parts was £244.24.

From the April, as a 40-year old vehicle, it had fallen into the "historic" nil band for V.E.D. and no M.o.T. test was necessary.

Taxed and insured, it was taken onto the public highway in June for the first time since December, 2007.

Letter from Department of Transport headed "National Type Approval - Piaggio Vespacar."

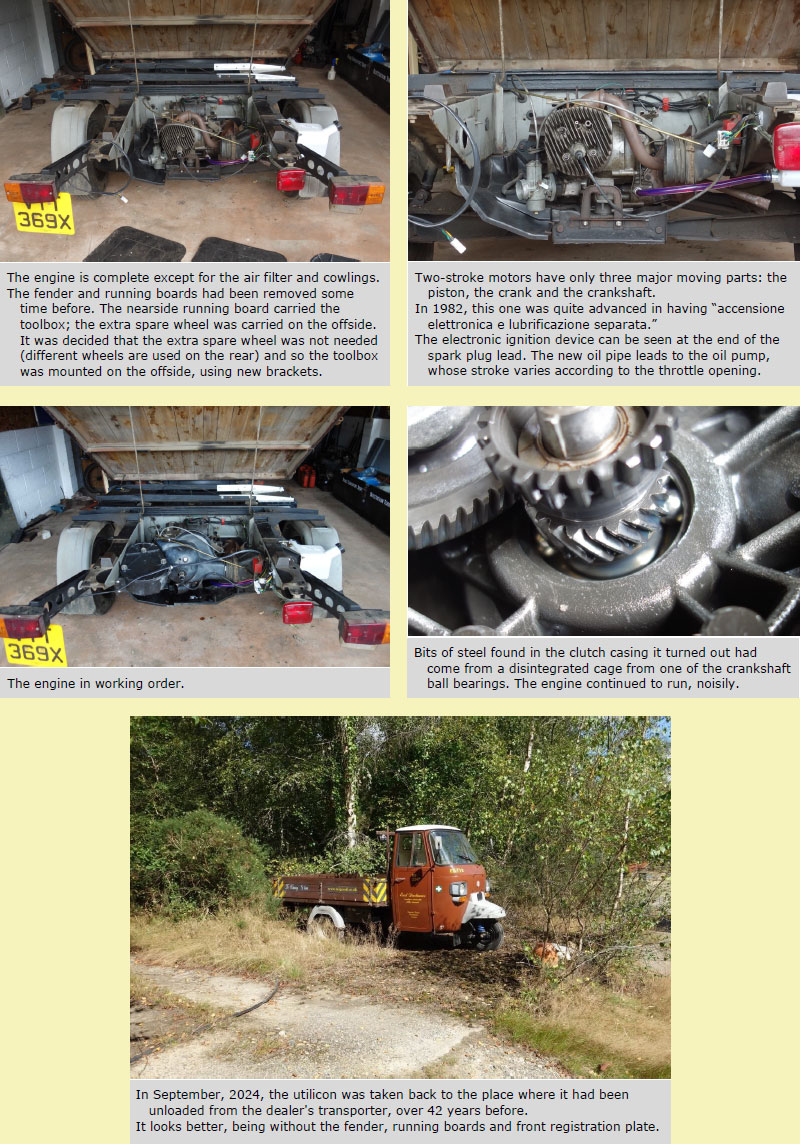

BEE 2309 (Overhaul)

After 16 years in service, the "new" utilicon had started to show its age. With the exception of the failure in 2010, thought to be the result of a manufacturing error, maintenance until 2023 generally had been routine, but now the fitter was faced with considerable extra work.

The first sign of age was the seizure without warning of the front suspension swing arm. On the older utilicon, failure of the pin and needle rollers would cause the front wheel gradually to tilt towards the steering column; there had never been a seizure.

The steering column, spring, damper and head bearings were replaced, and the wheel arch repainted in October, 2023. Work continued in 2024 with replacement of the front engine mounts and the elastic couplings on the drive shafts. The front wheel arch and the underside of the cab were patch primed and coated in Tetraschutz.

The timing belt had been replaced when the water pump seized in 2010. It was thought to be overdue for renewal but there was no mention of the mileage interval in the Service Station Manual. All the advice was that belts are more likely to fail because of age and 13 years was far too old. Eventually, an electronic copy of the Variante al Manuale per Stationi di Servizio was obtained from Vespadoc and this revealed the kilometre interval for the "sostituzione cinghia commando distrib." is 40,000. When the belt was replaced, the mileage had been nearly 3,000 in excess. It is assumed that this is an "interference" engine; if the timing belt snaps, the piston will hit the valves. This could have been determined when the belt was off.

Many minor jobs were done as well, including fitting a reverse gear sensor to substitute for the one attached to the gearbox which had failed when new.

Introduction of the new utilicon.

WASP S 4943

This Ace "Aristocrat" "static" caravan was made in 1974 and must have had a very short stay on a holiday site.

It was bought by the railway from a farm near Sheepwash in 1985 for £800. Like the one bought in 2019, it was the only caravan viewed and was chosen almost straight away; in this case because of its modest size (27'-0" x 9'-6") and style; it must have been one of the last statics that looked much like a large tourer.

At ten years old, it was already in poor condition. The bitumen Flashband applied to the edges of the roof made it obvious that there had been leakage and it was found later that this had caused the wooden framework to rot in one corner.

Extensive repairs, modifications and repainting were completed in 1987, and it had hardly been touched since then, except for the provision of new equipment and the reinstatement of the flush toilet.