The scout does not remember where he had been before, if anywhere, but he recalls spending the night in a platform waiting room at Birmingham (New Street) and catching the first train to Machynlleth, where he went into town for some breakfast before continuing to Towyn.

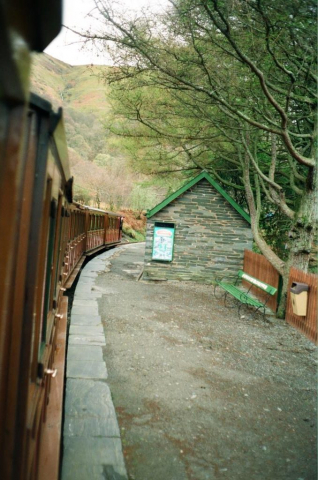

There, he made his way along to Wharf Station and caught a train to Abergynolwyn; he doesn’t remember going to Nant Gwernol.

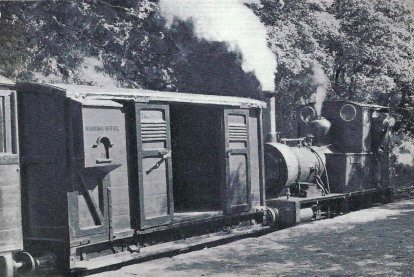

The 2 ft. 3 in. gauge Talyllyn Railway was opened in 1865 to serve the slate quarry at Bryneglwys, in the area dominated by Cader Idris. A passenger service was run between Towyn Wharf and Abergynolwyn. The quarry closed in 1948 and Tom Rolt and his chums embarked on their “adventure” in 1951. Their effort was the inspiration for “The Titfield Thunderbolt,” the classic Ealing comedy of 1953, which Rolt had hoped would be filmed on the line. It is thought that the railway had not been nationalized in 1948 simply because it was overlooked. Passenger trains began running through to Nant Gwernol, at the foot of the former rope-worked incline to the quarry, in 1976.

The original stations were (O.S. spellings): Wharf, Pen-dre;, Rhyd-yr-onnen, Bryn-glas, Dol-goch and Abergynolwyn. The railway’s name (the O.S. spelling is Tal-y-Llyn) came from the lake above the Afon Dysynn river.

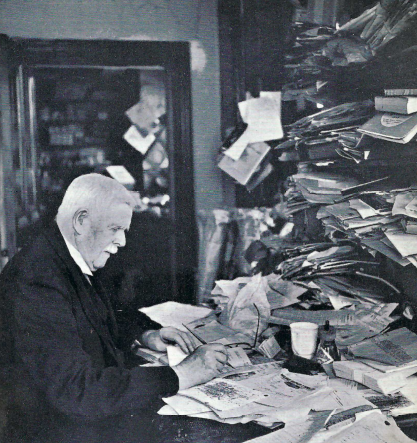

In 1953, L.T.C. “Tom” Rolt wrote of his discovery and subsequent saving of the Talyllyn in “Railway Adventure,” a copy of which the scout’s Mother had bought from The Country Book Club. It was the 1962 edition, the profits from which the author had dedicated to the preservation society he had helped to form.

The Foreword by John Betjeman gives a flavour of the story.

“Railway with a Heart of Gold,” an American film-maker’s humorous tribute to the Talyllyn Railway Preservation Society.

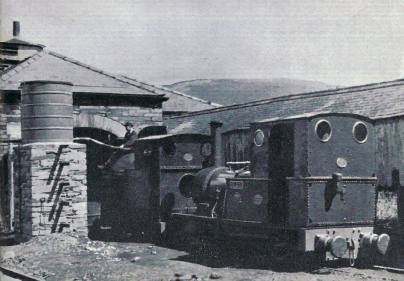

The scout had read “Railway Adventure” when he was a lad, having been surprised to find it on his Mother’s bookshelf. He had read it at least once more by the time he set off to see the line, and Tom Rolt’s story and the stitched insert of black and white plates were etched in his mind.

The modern reality was not a shock but it was somewhat disappointing, the scout remembers. “Limited clearance” signs, men wearing B.R. orange vests, the neatness and fussiness, all conspired to diminish the dream. The people, the cars, the “merchandise,” even the colour, were an intrusion. Read the book but don’t watch the film, it might be said, for the film will supplant what the reader has imagined for himself.

If Rolt were to awaken and return, he would be astonished at the bulk and complexity of regulation that is now necessary even to run a seven-mile narrow gauge railway. The safety case and the risk assessments; the exams, competences, compliances and methodologies; and all kinds of statements on such unheard of things in his day (or even in 1989) as equality, diversity, disabilities, access, slavery, hate, hurt, intimidation and whatever else may be demanded. From being forgotten in 1948, even little lines like this are now watched by the ministry (government’s Office of Rail and Road) and a mishap on one will draw attention to all.

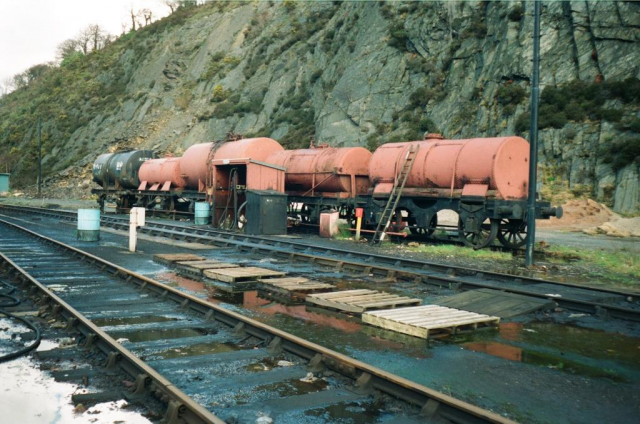

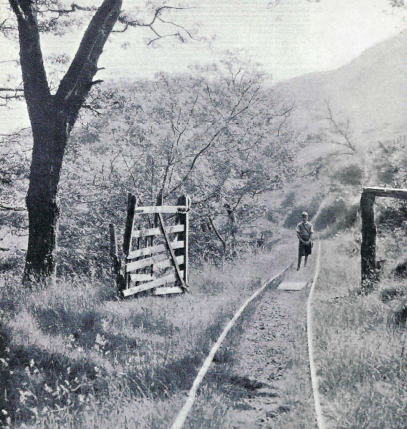

Worn out railways were once common and were often still in use in their worn out state, just as machinery, forklifts and suchlike are in small businesses now. The days of a driver not being sure that the road ahead was there until his engine ran onto the rail ends and the other ends sprang up from the grass, naturally could not last. Lines found on the edge of dereliction had to be made safe. Then they were improved; and bit by bit they were developed and enlarged, until the crumbling chateau became the prissy home of an English settler, obsessed with “do-it-yourself” shittery.

A request for a slate wagon to be attached to the tail of the train so that it might be gravitated back to Towyn after the family had picnicked beside the line of an evening, an arrangement that was once possible, would today be rejected by a booking clerk, whose forced smile would turn to a look of horror instanter.

The Talyllyn, like an old man itself, would have passed away soon after Sir Haydn did in 1950. But young men came and saved its life. In the early years of “preservation,” the character persisted, if only on life support, as captured by the American’s film. Over the years, the legacy lived on but, by necessity or through ambition, the wrinkles, quirks and old age failings gradually went.

Some might have preferred that it had died so that their fading memories would be unsullied by reality. Black and white images would be the only record, when living memory was gone, as paintings and drawings are of stage coaches and warships under sail.

Could a functional railway, outdoors, be kept permanently as if it had just become disused, or in a not quite ruinous condition? Perhaps the only alternative, for men who appreciate the air of neglect, is to find or create a place and keep it to themselves.