Sequence of Coastal Main Line Chapters

Great Western Main Line West of Exeter Route Resilience Study

This was written before the Dawlish Débâcle in 2014:

The chapters above, with some additions, are collected in a PDF: Dawlish Sea Wall I

Events from 2018 to the present (April, 2024) are published only as a PDF: Dawlish Sea Wall II

>> Autumn Budget, 2021 >>

>> Dutch Reach >>

>> Transport Decarbonisation Plan >>

>> Roads Policing Review >>

>> Man with a Mission >>

>> Newton Abbot to Heathfield >>

>> Petit Petition >>

>> Moretonhampstead Station >>

>> Railnews >>

>> Drink-Driving: Still a Laughing Matter >>

>> Priority Transport >>

>> Tunnel Vision >>

>> Traffic in Towns >>

>> I'm only asking the state... >>

>> Dave Black - Vassal of the road lobby, yesterday's man >>

>> Gridlocked Devon >>

>> The Network Rail Roadshow >>

>> Lynton & Barnstaple Railway's Bid to Continue Reconstruction >>

>> Following the Débâcle … >>

>> Great Western DNA Found >>

>> Great Western DNA Found >>>> The muddle of modern Italy compared with the splendour of Ancient Rome >>

>> Greens too green to govern? >>

>> Letter to Western Morning News, 4.2.15 >>

>> Heathfield Station >>

>> Devon County Structure Plan, 1995 >>

>> Fleabee - the lo-cust airline >>

>> Friends of Ashburton Station >>

>> Great Western Main Line West of Exeter Route Resilience Study >>

>> The costs entailed in keeping disused railways disused >>

>> The Dawlish Débâcle >>

>> 'Council leader wants remainder of Moretonhampstead Branch closed' >>

>> Letter to Western Morning News, 14.02.14 >>

>> Letter to Western Morning News, 21.02.14 >>

>> Letter to Western Morning News, 18.12.13 >>

>> B.R. ceases to be >>

>> Greenwall Lane Bridge >>

>> Letter to Western Morning News, 9.3.13 >>

>> Perridge Tunnel >>

>> Letters Appendix >>

>> Green Groups >>

>> Boots the Chemist >>

>> Rail Transport Services >>

>> And the traders—what do they care? >>

>> Stover Canal Society threatens railway >>

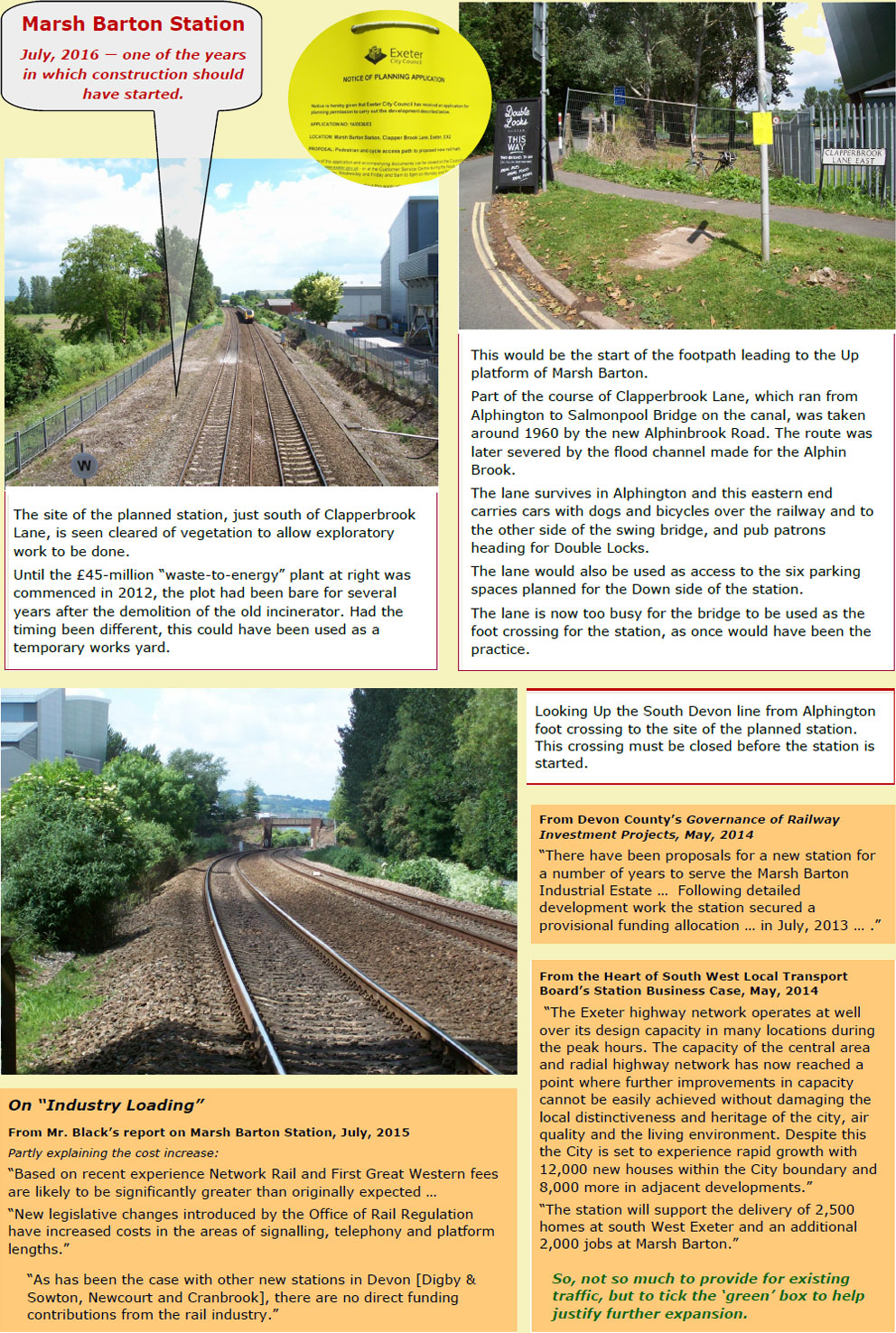

>> Marsh Barton, Exeter >>

>> Friends of the Atlantic Coast Line >>

>> Local Transport Plan, Three >>

There is something heroic but at once tragic in the claim that the E. & T.V.R. is unique in campaigning for a real railway: a system that is general purpose, expansive and deserving of much greater importance in the overall life of the country.

Many people show little interest in the world around them and have no idea what forces decide its makeup. The average motorist, for example, can imagine that the infrastructure and service provision that enables his free movement is the result of some great fortunate accident in an entirely natural process.

Those who choose to ignore, or are not aware of, the pressuring and machinations that are instrumental in bringing about so much of the structure of civilization and society, often rather resent being informed. It is perhaps in the nature of folk to feel peeved when introduced to a subject never before given any thought.

If any reason need be given why one form of transport should be championed loudly and boldly, it is because another has been heavily promoted behind the scenes, in the corridors of power, while playing on an easy attractiveness to ingrain itself in the minds of simple, unquestioning men.

The reader may go away and make enquiries but he will not find one railway, or what resembles a railway, that concerns itself with any more than its own restricted realm, be it territory or traffic. Not one of today's big industry players has a vision of an all-embracing national railway, now or in the future. Commentators only fix upon block freight and the hordes of passengers thrown up by a restless, growing population. A vast body of men who profess to support the railways, but who themselves happily subscribe to road transport at every turn, merely indulge in historical re-enactment or some such escapism.

There is certainly no power or influence remotely comparable with that of the Great Western Railway, one of the four big nominally independent companies to be nationalized in 1948. Given the management of the Great Western up until then, it is impossible to believe that such dynamism would have decayed, allowing it to watch its trading position being undermined and to capitulate business and capacity in the meek way that the state-run system went on to do, lacking the means to defend itself.

Had it continued, no devotee of the Great Western could bear to think of it becoming like a contemporary blue chip conglomerate, with cutthroat executives chasing and grasping market share, but if only some of this modern ruthlessness had been adopted, what a difference it would have made to the balance of transport in the succeeding years.

If it is understood that the road transport revolution went along with the decline of the railways, would it not have been harder to make the case for new roads, more and bigger vehicles and disintegrated development if a modern, sophisticated rail system had demonstrated that alternative expansion, with all its town and country despoliation, was not necessary?

Suppose the road protestors' best ally had been the railways, objecting to the unfair advantage being given to their competitors, demanding equal terms and advancing counter plans of their own. Imagine environmentalists having industry at their side in the form of transport operators not afraid to damn the opposition for its huge land-take, wanton energy consumption and degradation of human life and habitat.

It could be said that the whole rationale of the massive changeover to road transport depended on first destroying the railways, or so neutralizing their position that they could not compete or protest.

The railways had very little voice after government control was taken in 1939 and practically none after 1948, when the road lobby and its largesse attained supremacy. A faint, heroic cry was heard from Edward W. Burkhardt at the 1995 denationalization but he was quickly silenced. What hope was there that a fragmented industry, lacking pedigree railwaymen, led by a generation detached from history, would know what to say even if it could find a voice?

Must we always be monstered by the mass media?

When claiming that the E. & T.V.R. spokesman champions the railway as an industry lobby should do, it is understood full well that his words and actions make no difference. One man's carping from the shadows at the back of the hall can never be heard above the shrill choirs of the road interests. A lone rebel cannot counter the forces arrayed against the railway or make up for the weaknesses of its structures or the muteness of its adherents.

Proof that the Teign Valley voice, though faint, is unique comes from Sim Harris, Editor of Railnews, writing under the heading above in the September issue about sensationalist hacks repeatedly distorting the truth and poorly portraying the industry. After asking "who is speaking up on behalf of the railway?" he says:

"The rather grim conclusion is that there is no one—no organisation—which is willing to take the gloves off and speak assertively and authoritatively about the industry as a whole, without any wretched public relations 'spin' (such as when the DfT suddenly discovered that electrification was 'disruptive' recently).

"We don't need spin. We do need to speak loudly and clearly about the benefits of rail without dressing them up. And we do need to take on the critics on their own terms, and at their own level."

The Roadshow Continues

Four separate chapters in "Campaigning" tell the sea wall story after the disastrous débâcle of February, 2014.

The account was not kept up, which has resulted in all the events since 2016 being described together.

Two appendices contain the whole ten-year saga:

Dawlish Sea Wall I finishes with Network Rail's first roadshow at the Langstone Cliff Hotel in 2016. This contains the four published chapters with some additions.

Dawlish Sea Wall II begins with the public airing of the South West Rail Resilience Programme in 2018. This is only published as a PDF.

Autumn Budget, 2021

Unheeded advice to the Chancellor on transport investment

In September, followers of Transport Action Network were urged to add to the pressure on the Chancellor of the Exchequer to cancel the £27-billion "Road Investment Strategy II" programme and fund instead measures to advance sustainable forms of travel and transport.

https://transportactionnetwork.org.uk/tell-rishi-sunak-to-stop-funding-ris2/

As a token effort, the scribe, part he hoped of a dispersed team, picked up his pen, knowing that what he wrote would be scanned by some artificially intelligent device, made into a meaningless statistic and ignored.

"The desire to continue building roads must come from a belief that there will be like-for-like replacement of existing vehicles by electric ones and, fatally, that their number will grow."

The longstanding fixation with spending on roads to facilitate self-centred transport should have ended long ago, but politicians generally have never been able to see what lay beyond the "Great Car Economy." Now it has become doubly urgent that sustainable transport, in all its forms, is given every advantage, for the health of the nation and the good of the planet. Throughout the necessary revolution, it should be possible to "balance the books," but more important than this is the unaccountable human wealth that will accrue.

Infrastructure and Construction

Any fears that winding down the roads construction programme would mean less work and prosperity should be allayed by consideration of the vast potential that exists for expansion of the railway system, tramways and other public transport.

Coupled with the development of the support and supply industries, which this country once had in abundance, and a great easing of the regulatory burden that now artificially inflates costs, many more schemes could be pursued. These would bring great long term benefits to the population and advance the present environmental imperative of ending the subservience to "Big Oil."

Manufacturing

Instead of devoting enormous resources of labour and materials to the churning out of what has become the most wasteful consumable, the private motor car, a transition should be made to a manufacturing economy that enables and encourages production of much longer lasting, better designed and built, vehicles of all kinds, chiefly trams and buses.

A consistent and continuous programme of railway electrification would stimulate exporting industries, as well as providing a low energy transport spine, essential if the country is to meet its carbon reduction aims.

Transport Spending

The ridiculous roads programme, Road Investment Strategy 2, could have been lifted straight from the pages of a 1970s policy document, when transport spending was dictated by the roads lobby, despite it having been understood for many years that "suppressed demand" would lead to more and more traffic filling new roads.

The emphasis now must be on reducing motor traffic, whether propelled by oil or electricity; reducing the need to travel where possible, by such means as fully-functioning neighbourhoods; greatly increasing travel by public transport; and making safe and attractive so-called "active travel," which would lessen the strain "sedentary" illnesses put upon the N.H.S.

The desire to continue building roads must come from a belief that there will be like-for-like replacement of existing vehicles by electric ones and, fatally, that their number will grow. All new road building must now be curtailed, a move the Welsh Parliament has made, and the processes reviewed according to prevailing environmental standards.

Transport Taxes

Buchanan famously stated in his 1963 report: "Except for the smoking of tobacco or the drinking of alcohol, there is no way of laying out the citizen's money that has proved easier to tax than the owning and using of motor vehicles."

While seemingly never tiring of this, motorists bleat about the injustice while overlooking that the cost of motoring has actually fallen, aided by reductions of tax and duty. The notion that choked roads are an indicator of a thriving economy must end because it is at odds with the new environmental awareness. The physical and societal damage done by motor transport must be recognized and undone. Nothing will be achieved if tax incentives to electrify the road system lead to the same congested roads.

Taxation of electric vehicles, which soon will be all that can be bought, should be introduced immediately, both to curb growth in ownership and encourage use of genuinely benign modes. Equally, for the remainder of the life of oil-driven vehicles, the Fuel Duty Stabiliser should be reactivated.

Neither lorries nor freight trains have to bear their full "track costs," but hidden subsidies favour road freight far more, operators of heavy vehicles paying practically nothing for the wear and damage done to public roads, which is out of proportion to the weight imposed.

Air Passenger Duty must remain and be at a sufficient level to persuade domestic and continental fliers to use surface public transport. Aviation fuel should be taxed at the same rate as DERV to dampen demand for the most polluting form of transport.

Tax relief or grants should be given to firms or individuals wishing to substitute the likes of cargobikes and cycle rickshaws for conventional vehicles.

November, 2021: Four days before world chieftains and their entourages flew to Glasgow for a fortnight of prattle and waffle about climate change, the chancellor delivered a budget that made not so much as a nod to what briefly took over from the plague as the most pressing emergency of the day.

After a period of almost unprecedented peacetime expenditure, helping to keep nine million workers on gardening leave, propping up failing businesses and dishing out supply contracts with gay abandon, the chancellor dared not cause a rise in the cost of living and so decided to continue the eleven-year freeze on fuel duty and effectively cut the tax on domestic flights.

It was surely only a technicality that he cut the roads' budget from £27-billion to £24-billion, as the thrust of the budget was "business as usual," with the excuse, "I don't know what else to do."

Dutch Reach

Review of The Highway Code

Happily continuing the legislative lag between the senior form of transport and the rude pup, Department for Transport and its predecessors overlooked the countless deaths and injuries of vulnerable road users, the blighted and stunted lives, the lives that might have been, and all the concomitant misery and misfortune, and finally, in the year of the great plague, with many suddenly rediscovering foot and saddle, or so-called “active travel,” as a permitted escape from house arrest, decided that some effort should be made to improve safety.

The review of The Highway Code is better late than never, the scribe grudgingly will admit.

Remarkably, the Department consulted widely with concerned groups such as Living Streets and Cycling U.K., resulting in long overdue suggested revisions to the Code which are as favourable to pedestrians, cyclists and horse riders as it is possible to be under the present system in one advance.

The principal change would be the establishment of “a hierarchy of road users which ensures that those users who can do the greatest harm have the greatest responsibility to reduce the danger or threat they may pose to others.”

Perhaps a hierarchy of responsibility would be better than a hierarchy of road users, for the aim should be equalizing, not dividing, individuals.

“Presumed liability” has been enforced in all but five European countries for some years, so what is proposed here is typically a very late corrective measure.

An item in a newsletter from Roadpeace, one of the charities consulted, alerted the scribe to the opportunity to respond, which was open from late July until late October, 2020.

"...in the present state of motor traffic I am persuaded that any civilised system of law should require, as a matter of principle, that the person who uses this dangerous instrument on the road dealing death and destruction all round should be liable to make compensation to anyone who is killed or injured in consequence of the use of it. There should be liability without proof of fault. To require an injured person to prove fault is the gravest injustice to many innocent persons who have not the wherewithal to prove it."

Lord Denning, 1982

A novel safety tip was revealed under “Waiting and parking.” “We are recommending that a new technique, commonly known as the ‘Dutch Reach’, is introduced to this chapter. This advises that road users should open the door of their vehicle with the hand on the opposite side to the door they are opening. This naturally causes the person to twist their body making it easy to look over their shoulder and check for other road users. This will help to reduce the risk to passing cyclists and motorcyclists, and to pedestrians using the pavement.”

This of course would apply to the driver and his passengers on both sides of the vehicle. The pavement may also be a cycle path.

Roadpeace published copies of its own responses but the scribe confined himself to “yes” and “no” answers, merely adding some final comments.

Rule 67: Half a metre is scarcely enough safe clearance from a parked vehicle, even if occupants opening doors exercise the “Dutch Reach.” Without this precaution, 0.5 metres is quite insufficient.

The existing general ignorance of The Highway Code comes from most motorists never having referred to it again after their driving tests. None of the long overdue changes can have any effect unless they are widely disseminated through public information broadcasts, advertisements, targeted social media messages, etc.

A very great help in this regard would be examples of the new rules being applied in real situations.

By far the greatest delight for the scribe will be seeing these alterations enacted for the good that they must do; but he will take some pleasure from hearing the squealing simpletons of The Lost Valley, who think of cyclists - or really anyone not behind the wheel of a Wankmobile - as "road vermin" or "morons," when they discover that their carelessness and callousness will hurt them.

"It may come as a surprise to many to hear the UK is probably the worst place in Europe

for a cyclist to be injured by a motorist."

Richard Gaffney, Principal Lawyer, Cyclists' Touring Club

https://www.slatergordon.co.uk/newsroom/cycling-accidents-and-presumed-liability-uk-vs-europe/

Transport decarbonisation plan

A call for ideas from a department that has long ignored them

In July, 2020, came a prompt from Campaign for Better Transport: "How to shrink transport's carbon footprint? Have YOUR say."

The Campaign suggested some answers but the scribe chose to have a go at the dopey department using his own words.

What should be done to reduce the greenhouse gases that are produced from:

Cars?

Out of exasperation with the rising cost of rail electrification, rightly always seen as the apogee of a powered transport system, government has effectively fallen to electrifying road vehicles, as if this were a simple answer. But replacing 30-million oil-powered vehicles with battery-electric equivalents would unleash possibly worse environmental damage overall and would do nothing to relieve traffic congestion and a host of other problems caused by the general over-dependence on motorized road transport. Vastly reducing the number of cars is needed, not just to curb greenhouse gases, but to deal with other environmental degradations, not least of which is the extravagant consumption of materials.

Passenger Rail?

What should have commenced, at the latest, in the 1930s and been completed in the 1970s, electrification of the rail network, would have provided a spinal transport system that could have run on any fuel and positioned the country well to face, or perhaps avoid, environmental challenges like the one in view. Nothing represents government failure more than the crackpot "bi-mode" train, which is sure to be used as an excuse to curtail electrifying the network. Ultimately, the least damaging and best form of passenger transport over land is the electric train.

Q18. What other views do you have on how to decarbonise the UK transport network?

As with electricity generation and food supply, it should first be established what is actually needed. If waste were eliminated and efficiency concentrated upon, the question would remain: Where and how shall they be obtained?

Cheap oil is responsible for setting the whole world in motion, with the result that people and goods move under power far more than is good or necessary.

If there is to be a revolution in transport provision, tackling pollution on its own and attempting to perpetuate at all costs the great car economy is the wrong approach: far more needs to be done to reduce the need to travel and for goods to be moved.

Zonal planning, which has caused excessive movement, or designed-in unnecessary movement, through such abominations as out-of-town shopping centres and sprawling housing estates, should revert to the high-density mix that had evolved before the car made mobility a curse. Homes with space for two cars, and offices and works with enormous car parks, make everywhere bigger and more dependent on road motor transport.

As many people as possible should be absorbed by public - or "shared" - transport, and this should take more forms than it does now and be less regimented.

Q19. Any other comments?

The motorist's demands that he drive wherever and whenever he wants, as far and as often as he likes, in this crowded island; that he park his car in narrow streets in ancient towns and cities, and in the most exquisite countryside; that all else get out of his way; that enough road space materialize, as if by magic, to meet his and many million others' needs; these demands, often dictated by his actions, are an absurdity.

Yet it is this demanded "freedom" that government has spent a hundred years facilitating at every turn; bowing slavishly to vested interests; believing it to be the only path to economic growth; being fearful of disregarding the public's childlike clamour; and of course happily milking the tax cow. Even as government sets about decarbonizing transport, the road construction programme does not falter, as if the future can hold only more of the same, but battery powered.

The modes that today are needed are the ones that over the same period were allowed to wither, often as a price to be paid for a motoring utopia. Buses and trams were lost; walking and cycling became less popular and more hazardous. The greatest damage of all was done to the railway system, which, if it had been allowed to make the difficult metamorphosis from the steam age, promised to become a vast, modern network operating in its own reservation, able to move large numbers of passengers and great quantities of goods in all directions, by night and day, under all conditions. It was one of the country's greatest assets—a British birthright—which could have set the whole course of transport development.

Instead of making this possible, the railway was undermined and, in great part, destroyed, by continual acts of sabotage; a quarter-century of chaotic denationalization, spent rediscovering that unified railways work best, is just one example; the advice this year to "use your car, not public transport" could be the latest.

Never with any real vigour were the disbenefits of private motoring and trucking tackled. Those who chose, or had no choice but, to walk or cycle or use public transport have been hugely disadvantaged. Air pollution is reckoned to kill as many per year as the plague has done this year, and with less discrimination; the great health time bomb, obesity, brought on by inactive lifestyles, will probably kill more in time, yet these crises do not cause stoppages.

A pair of boots; a humble bicycle; an omnibus; a lightweight van; a tramcar; a tub on a man-made waterway; a pair of rails to make the energy go further and a wire above to collect juice made from wind and sunshine; they are all staring at the Department for Transport, but the department whose crowning creation is the utterly hellish road system asks the public how to decarbonize transport.

Response to Transport Decarbonisation Plan: call for ideas

Roads Policing Review

Call for evidence

Richard Martin, the Police and Crime Commissioner's assistant, kindly wired on 13th July, 2020, inviting the railway to make a submission to the review before the closing date of 5th October. This was the first of a rush of consultations in July.

The Foreword begins: "Great Britain has some of the safest roads in the world but there is no room for complacency and this government is committed to making our roads even safer." But the Department for Transport is concerned that "since 2010 we have seen a plateauing in the number of people killed and seriously injured on our roads after years of steadily declining numbers."

If there were five fatalities and 68 serious injuries every day on Britain's railways, as there are on Britain's roads, or even casualty figures relative to the share of traffic, the scribe cannot help but wonder whether it would have taken ten years to think about a review.

Here is an extract:

Current offending behaviour

The railway provided brief answers to 14 questions.

Man with a Mission

Should anyone detect a missionary's zeal in the themes on these pages, there may be some hereditary explanation. My grandfather on my father's side, Revd Richard Burges, was General Secretary of the India Sunday School Union in the years when it was seen to be the duty of the church to convert heathens throughout the empire to Christianity.

Legend has it that a telegram once reached him addressed simply "Burges, India." While letters have found me with only the vaguest idea of my address on the envelope, it has to be admitted that "Burges, Teign Valley" hardly compares with a subcontinent.

My grandfather I feel got the better posting. He was supported by the British Sunday School Union and received gifts from the non-conformist philanthropists, W.D. & H.O. Wills, who may not have approved of the anti-smoking campaign he conducted. He lived very comfortably and a great number of natives was receptive to his teachings.

Trying to bring civilization to the unguided of the Lost Valley through the agency of rail transport, unpaid, is utterly dispiriting. At least savages had the decency to put missionaries in the cooking pot; here the bringers of enlightenment are just ignored by the apathetic and detached, wedded to cars and material consumption.

A pamphlet, "Our Sunday Schools, Their Achievements & Possibilities," found on the electronic babel, has allowed me to read my grandfather's words for the first time. It is a paper read before the Calcutta Missionary Conference in 1898, the year my father was born in Darjeeling.

Naturally, I was curious to know if any writing characteristic had come down the line, even without contact; my grandfather died in 1947. There is none, except perhaps a weakness for alliteration. I found "no lady of title or talent." And "The India Sunday School Union is already crippled for the lack of lakhs, but its troubles would increase if each of our seven thousand teachers claimed financial payment for his work."

Today, I would risk arrest and imprisonment if I were to use language such as: "THE HEATHEN PRINTING OFFICES ARE FLOODING THE COUNTRY WITH LITERATURE FOR CHILDREN." However, substitute "roads lobby" for "heathen" and it could be a refrain of mine. And, especially with a railway fraternity that needs sparking into life, I would have every justification in using the pulpit cry my grandfather added: "SHALL WE LOOK ON AND BE IDLE?"

Revd Burges asks: " … what more spiritually invigorating to many who are dying of soul-inanity than an hour spent in building up a Sunday School … ?" Dying of soul-inanity, eh? He was fortunate that he did not live to get sucked in by the infantile, banal and often uncouth posts on the Lost Valley's Mughook pages.

"The drink is a hydra-headed monster which it is the duty of the Church to strangle," were not his words, but it was clearly his thought. I confess to some ambivalence towards liquor but in one regard I leave no doubt, made known in "Drink Driving: Still a Laughing Matter."

"India is a country without a Sabbath. The big wheel of activity rushes on without a rest. On the river and on the railroad, in the mill, and in the street, in the field and in the family we see ceaseless toil all round the year."

The passage above and "if gospel bells are to ring out over this cheerless heathen land" could have come from a writer about modern Britain. C.B.

https://archive.org/details/oursundayschools00burg/mode/2up

The India Sunday School Union, founded in 1876, is still going strong.

Newton Abbot to Heathfield

The remnant of the Moretonhampstead Branch and once part of a diversionary route

The most recent attempt to make some use of this four-mile line, dormant since the last train traversed it in 2015, has come from Heath Rail Link, formed in 2017 as the Newton Abbot to Heathfield Railway Revival Group.

This is the third in the last ten years to have landed upon the line, which at first looks as if it could offer a comfortable home to preservationists or be developed as a functional public transport operation, or both.

The report appears under "What's New" because the railway has stepped back from deep involvement, convinced that no project like this can be advanced in any worthwhile way under present conditions.

If the near five hundred "supporters" on Heath Rail Link's Mughook page were to pay a subscription to Railfuture, or send a donation to Campaign for Better Transport, or form a pressure group of their own to agitate locally, this may still not bring results but it would surely do more good than chattering about reopening a short, residual line which would make little sense on its own and is beyond the capacity of any power but the state. That "supporters," for the greater part, resolutely do not subscribe or donate or take part in debate about the wider issues, actually suggests that they are not much interested in the provision of practical rail transport.

The only action that warrants inclusion here has been a message to Bovey Tracey Town Council, which it was hoped would bring a measure of realism to the exchanges.

Appendix: Message to Bovey Tracey Town Council

The last train to tread the metals passing Teigngrace: https://youtu.be/6zFpOyefoQ8?t=219

Heathfield - Newton Abbot Community Rail Project

March, 2020: Teignbridge District Council has submitted a bid to the "Restoring Your Railway" fund.

Petit Petition

To: Chris Grayling, Transport Secretary

It was not the railway's idea to start a petition calling upon a government minister to order a thorough appraisal of diversionary routes. The prod came from campaigning organization 38 Degrees, reacting to one of many news reports about train service disruption on the coastal main line.

A wire was received from the organization's Kieran Maxwell suggesting that someone should set up a petition. This can hardly have been computer-generated, although it may have had an element of automation. It must have stemmed from human initiative, from someone picking up local news stories to see if any would warrant a campaign being started.

While not imagining for a moment that there would be any meaningful result, the approach was considered worth acting upon, if only as a test.

The campaign page was headed "Railway Diversionary Routes," and called upon Chris Grayling, Transport Secretary, to "Engage an independent consultant to examine and cost the reinstatement of former railways which connected Exeter with Newton Abbot and Plymouth, and which provided diversionary routes when the line through Dawlish was closed."

In the box marked "Why is this important," was entered:

"No amount of money spent on the coastal route will make it invulnerable and arguably some of what the fantastic schemes being proposed would cost should be spent on route diversity.

"Rail passengers will accept being diverted in an emergency because they remain at their seats and know how much longer their journeys will take."

The next step was to send messages urging individuals or members of groups to sign the petition, a mere matter of two clicks.

Now, there are some issues which excite people to the extent that a call to action quickly has large numbers responding. Once word went around of a petition concerning one of these issues, a runaway effect would have each person signing getting another, or two or three more, to add weight, and so on.

Railway supporters are not like this. While there were more signatures than messages sent, it is clear that few, if any, were able to propagate the campaign by mobilizing a list of contacts; some messages did not even result in a signature. The scribe has the petition but it will not be published.

The group representing those most likely to benefit from a reinstated Southern diversionary route, Okerail, seemed reluctant to carry the post on its Mughook page, any move by the Teign Valley, or other outsider, seemingly being viewed with suspicion, and the response was all of nothing.

By way of an agent, a post was made on the Teign Valley Mughook pages, subscribed to by over thirteen-hundred locals who revel in having an outlet for their banal chatter.

To most, the reinstatement of the branch railway looks like an impossibility and therefore little thought is given to the idea. Yet such reinstatement, even in a basic, modern form - that is without staff or facilities at any intermediate station - would be the most lavish provision of infrastructure imaginable in this lost valley, carrying with it the power to widen transport and travel choices for a great many.

Of course, there would always be those who insist that the railway would do little good, or no good at all; that few people would use the local services; and that its value as a diversionary route would be minimal, not worth the cost of providing it. Some, justifiably, would be concerned about the environmental damage or disruption.

Naturally, proponents of railway expansion will claim that while there will often be undesirable results when any great scheme commences operation, the overall effect of railway reinstatement would be greatly beneficial, a result that all previous examples prove without doubt.

And to the environmentalists, whose concerns the railway industry, as both promotor and provider of sustainable transport, would give the utmost attention, it would have to be stressed that reconstruction would be far less disruptive than building a line where there had not been one before.

Even allowing for the Teign Valley intelligentsia not being represented on the Mug pages, the post should have generated some discussion; far less important subjects often attract lengthy outpourings of bile and misinformation. Some sign of life, at least, may have been shown by talk of reviving the Teign Valley Action Group* if ever railway reinstatement became a serious prospect; or by a threat to derail the first train; or by a young blade declaring: "We don't want none of that buplic transport ere."

On this occasion, out of the more than one thousand, three hundred subscribers, whose pap and prattle generally fills the page, how many were persuaded to sign the petition? The answer is three.

The post attracted only one comment, from the man whose father, a successor of the original owner, paid a pound for it when a mile of the line was sold off after closure.

A deep well of support should have been found in the group hoping to revive the disused line from Newton Abbot to Heathfield, the remnant of the Moretonhampstead Branch and part of a former diversionary route. Well over 400 people have been admitted to the Mughook page, Heath Rail Link, and so a post was made there.

It succeeded in adding a few more signatures to the petition but also brought forth the usual damp squibs. It is strange that men who subscribe to a group with the aim of restoring a passenger service between Newton Abbot and Heathfield, would rather engage in pointless argument about detail and pour scorn on anyone who dares to think expansively, than simply sign a petition, which was deliberately plural in its title.

Most of the Mughook exchanges are reproduced in the following appendix. The carping tongues who took the time to compose numerous posts, could not be bothered, or wilfully refused, to make two clicks in support. The scribe had decided once before that Mughook was a useless campaigning tool. His thoughts were boxed in the Friends of Ashburton Station story. Foolishly, he returned; this time he has left for good.

Appendix: Mughook Comments about diversionary routes

Though the failure of this petition to attract even three-score signatures does not matter, it is telling of a malaise which infects the railway camp. Out of the thousands and thousands of people who profess an interest in railways, only a very small number joins campaigning organizations, whether the national Railfuture or local, specific-interest groups. Even among those who are active, there is often a woeful lack of ambition. The firm belief among middle-aged men that most movement will evermore be cars of some kind on the roads and that the railway network and its minimal functions can only grow incrementally, is hard to unseat.

Environmentalists who look to railway people, both within and without the industry, to put flesh on the bones of broad ideas of what railways should be doing and where they should be going, often do so in vain; the Mughook miseries mentioned above would more than likely smother them with a wet blanket. Anyone who looks to industry players to take the lead quickly finds that most managers and executives have little use for the system they control, scant knowledge of its historical development and no understanding of the vastly expanded role the modern railway could fulfil.

It was thought that maybe a few hundred would sign as a show of solidarity, but the total when the petition, out of embarrassment, was taken down stood at fifty-seven; God bless them.

If every member of every West Country rail user group, society and organization, including railway staff, were to have signed, it would still not have made a petition worth presenting to the minister. It is doubtful whether even a petition signed as well by every Teign Valley resident and those of Mid Devon and North Cornwall, and everyone who may at a stretch benefit from reconstruction of the former diversionary routes, would have had any effect whatsoever, such is the sparsity of population.

Fifty-seven loyal souls signing a petition may be a poor showing but it is still more energetic than the loose assembly that substitutes today for a rail industry, which, lacking voice and vision, has shown no interest at all in reopening the diversionary routes.

* Teign Valley Action Group was formed in 2000 to oppose plans to reopen Ryecroft Quarry.

Moretonhampstead Station

Housing development proposed where trains must in future go

In March, 2019, a planning application was submitted by Baker Estates Ltd., on behalf of B. Thompson & Sons (Transport) Ltd., for permission to erect 40 dwellings on the site of the former terminus.

In March, 2019, a planning application was submitted by Baker Estates Ltd., on behalf of B. Thompson & Sons (Transport) Ltd., for permission to erect 40 dwellings on the site of the former terminus.

The haulage firm that has occupied the station for most of the years since the line was closed, has restructured and now only needs the "town" end of the site, making redundant the area where the goods shed and part of the passenger platform still stand.

The railway has objected to this application, as it did in 2001 when permission was sought for 80 homes on the whole site. On the earlier occasion, the National Park Authority had fielded several subsequent applications, with the number of dwellings reducing to 51, and the matter was not concluded until 2004 when the Inspector's report on objections to the First Review of the Local Plan ruled that it was "much too premature to contemplate losing the employment use of even a proportion of the site."

" The sudden emergency which has been creeping up on us in full view for fifty years... "

In July this year, the authority was anxious not to be at fault when the call goes out, "Right, who hasn't declared a climate emergency?" For good measure, the committee resolved to declare a climate and ecological emergency.

Like all the other posturing from piddling parishes up to Whitehall, it is a quite meaningless move, based on the belief that, unlike other emergencies, this one can be dealt with by the least action: a long series of minor adjustments, when the situation, if it is as bad as is being made out, demands nothing less than rapid phase change.

It is like the self-professed conscientious soul disregarding the 50,000 gallons of kerosene he may be sitting above on the airport runway and later getting worked up about the one-use plastic straw brought with his in-flight drink.

In this case, the reality is that the authority will have no choice other than to grant permission for the development and thus obstruct the return of the railway to Moretonhampstead with miserable, volume homes, the majority of whose occupants will drive cars practically everywhere they go for work and play.

There were once 31 stations on or around Dartmoor; now there is but one. The Draft Local Plan, 2018-33 (in October, 2019, being prepared for examination by the Secretary of State) contains half a page on rail transport, with not one action proposed. "Electric Vehicle Charging Points" are given a page, resignedly accepting perhaps that the only answer is to use electricity to perpetuate the established disorder.

Without any guidance or mandates from government, even if there were a free-thinker who had managed to slip the manacles of the motor car, it is not for a cosy little authority like Dartmoor National Park to make a stand. If it had tried to be bold in the last Local Plan and insisted that the only development that would be permitted at Moretonhampstead Station would be the sort that could easily be adopted or displaced by the return of rail transport, the policy would surely have been struck out by the government inspector on the grounds that it would amount to "planning blight," there being no prospect in his view of the branch line being reconstructed from Heathfield.

An example of phase, or step, change would be some move towards rebuilding the railway system as part of a general revival of public transport. Even if, in the case of places like Moretonhampstead, it meant only a halt to the loss of what remains, it would still be a start.

Appendix: Letter of objection to the National Park Authority

Appendix: Letter of objection, 30th March, 2001

Appendix: Letter of objection, 13th August, 2001

Appendix: Letter of objection, 26th February, 2001

December, 2019: A new application was submitted for 35 dwellings, including three in the retained shell of the goods shed. Simon Hickman of Historic England had been good enough to write a personal objection to the loss of the goods shed, so perhaps his opinion helped to sway the developer.

As objections by the railway are made for the record, for a future unrecognized by planning policy, one will not be submitted on this occasion; there is also another consideration which will be revealed later.

A message was sent to the Parish Council, politely asking why railway reconstruction had not been mentioned in the council’s submission. A prompt reply was received which stated that “the effect of this development would only be to move the terminus 100yards down the line.” And: “The consultation period has closed, and we have already sent our comments.”

What will the Town Elders say when Thompson’s apply to develop the remainder of the station? And councillors should know that in practice comments are accepted until the case officer writes his report to the planning committee and that very late submissions are sometimes read out at the meeting.

The council was obviously not united in its view of the development because the chairman of the parish planning committee who signed the letter of support, dated 22nd January, the same day wrote to object on his own account. He did not mention railway reconstruction.

Appendix: Correspondence with Moretonhampstead Parish Council

Appendix: Personal Objection by Parish Councillor

March, 2020: Incensed by the report to the Development Management Committee containing no proper reference to the railway terminus, despite repeated appeals in the past that such historical installations be named, the scribe could not resist wiring some last-minute caustic comments at the case officer.

It is quite an accomplishment to write 32 pages about proposed development at Moretonhampstead Station and not once mention Moretonhampstead Station.

You do refer to the former railway and its remaining buildings but "Land at Station Road" hardly recognizes the original function and the one which dominated for nearly a hundred years.

Preserving a bit of the fabric treats the place as a transport curiosity with no relevance to the modern world. Yet, had there been a balanced approach to transport after the war, the branch line could well have remained open, leaving Moretonhampstead today as one of Dartmoor's gateway stations.

Twelve miles up the line, Teignbridge District Council has just submitted a bid for a grant from government's "Restoring Your Railway" fund, proposing to reopen to passengers the remnant of the branch from Newton Abbot to Heathfield. If this were to be successful, in changing times would future extensions to Bovey and Moretonhampstead be so unthinkable?

On Friday, with no choice but to do so, members of the authority will nod through a lousy-looking enclave housing estate with its 83 parking spaces, a development at the former terminus which incorporates no new thinking and most likely will be populated by people who will drive everywhere - even to the town - and have no sense of "place."

Last week, in Bristol, Greta Thunberg finished her speech to 15,000 excited followers with: " ... change is coming whether you like it or not."

Heaven forbid that it reaches the cloisters of Parke.

At the Bovey waxworks on 6th March, members followed the officer’s recommendation and nodded their heads in approval.

It's been too long since the scribe's Latin lessons for him to translate what could be the national park authority's motto, so, rather than cheat, here it is in our tongue:

We don't listen, we don't learn and an original idea has never entered our heads.

In December, 2019, the railway wrote to B. Thompson & Sons, asking if the corrugated iron hut next to the goods shed could be taken away and re-erected at Christow.

Ryan Thompson, Director, was kind enough to reply and said that he had forwarded the letter to Tom Biddle, Development Manager at Baker Estates. He added: "It's nice to think of preserving this little piece of heritage, if possible.

"The scribe telephoned Mr. Biddle on 18th. He advised that a new planning application had been submitted and promised to contact the railway when appropriate.

The application was approved on 6th March, 2020, and Mr. Biddle was telephoned again on 17th. He said that the Managing Director was to be at the station that morning. He would consider the request and discuss it with the demolition contractor.

Nothing more was heard and the building was demolished.

It was never closely inspected by the railway and it appeared in very poor condition, so perhaps its loss should not be regretted.

Railnews

Railnews

A letter to the Editor

Sim Harris is one of those establishment lackeys who draws a divide between the kind of railway expansion schemes that are deliverable within the narrow confines of today and those which are judged as barmy, even though they were once possible and could well be again in a modernized form if enough people believed in the full development of public transport systems and were able to use their imagination.

In a review of Campaign for Better Transport's "The Case for Expanding the Rail Network," in the March, 2019, issue of Railnews, entitled "Unbundling Beeching," Mr. Harris admits that there is merit in some of the proposals, but tends to sneer at or pick apart many of the other cases, especially where railway reconstruction would mean homes being demolished or, God forbid, a road built on an abandoned railway formation being displaced; even going so far as to say that "heritage" railway owners would object to their lines becoming truly functional again, as if their takeover would be any different to the exercise of state powers down the years. Would this be worse than the "People's Railway" of 1948 being thrown to a committee of vultures?

Railnews was first published in 1963 by the new British Railways Board to replace all the former regional titles. In 1978 it was issued free to staff; new entrants had been given an introductory issue. It ceased publication in 1996 but was restarted independently in 1997 and has continued since then.

The Teign Valley scribe received his free copy in May, 1974, but had actually started reading it much earlier, often being handed a copy on his way to school by a kindly booking clerk at St. David's.

Faced with all the institutional and entrenched opposition, whether overt or tacit; with the private car exerting a stranglehold on alternative thinking; with rail and other public transport innovation limited by closed minds or by its always being too expensive; there are still "railway" spokesmen and supposedly friendly commentators dictating what cannot or should not be done, even before the hostile voices from outside are raised.

Some men seem to delight in putting down proposals that would bring back rail transport to comparatively small populations and enable the railway to regain territory and areas of activity. Instead of being the ones brimming with ideas and writing encouragingly about every blossoming proposal, they are in the cripple siding pooh-poohing initiative, while congratulating themselves like smug intellectuals who can see why nothing should be done in given cases.

An intellectual will decide that a task is impossible and then sit back, satisfied that the power of his reasoning has saved him fruitless work. A lesser mortal may also realize that the chances of success are slim, but his spirit is disquieted by the lack of action and so the task is begun regardless, just to see what happens. Instinct cocking a snook at logic, perhaps.

If it is not on the scale of High-Speed Two or Crossrail, should a project not be considered? London Underground carries about as many passengers as the national network. Using the kind of figures that Beeching was fond of trotting out, if the Underground's small mileage were added to the country's, it could then be said that half of all traffic is carried on 2.5% of the network. Twice as many journeys were once made on trams than on trains. More passengers probably pass through one barrier at Waterloo in an hour than use the main line between Exeter and Newton Abbot in a day. In the end, it is easy to rubbish any call for expansion because of its lack of volume or intensity, if someone is so minded.

When listening to those who pronounce that there are quite enough railways, or that only a few more are needed to complete a useful network, it is often abundantly obvious that they speak as people who have cars very firmly planted beneath their backsides and who could make any journey they liked without using trains. The car is their primary, everyday mode of transport and if they were honest they would admit to being able to do without public transport of any kind, save perhaps "park and ride" buses.

Many would never stoop to using a local bus or train, and this goes for the majority of today's railway managers, who, like David Cameron being flown to Exeter before making his triumphal arrival in Dawlish, would only catch a local train for publicity purposes or when they can really do no other for the sake of appearance. They speak as if they do not know or care about those who are without a car; or those who cannot drive for one reason or another; or those who dearly wish to break away from car dependency; or those who feel that any journey beyond a certain length can only comfortably or properly be made by rail. The owner of a £20,000 motor car has only one consideration: the desire to be mobile when he pleases and as such he has little idea what the car really costs and does not see it as a waste if it stands in his driveway or other parking place for 23 hours on most days.

And those whose bottoms are grafted to their car's upholstery are not listening to the trumpet calls which may be sounding the end of the system that they have adhered to without thought or concern; the environmental groundswell that should make possible again a riot of diverse and widespread public transport provision.

If it were possible to involve communities in less stringent forms of railway operation, and the descent through a long life of rolling stock and materials were practised again, the religious pessimists who quote the multiple, man-made obstacles placed in the path of railway reconstruction today would have to recant.

Those to whom the car is the normal or preferred mode of transport can easily scoff at the people of Bude who met a few years ago to discuss putting the town back on the railway map. The former terminus of a branch from the famous Halwill Junction, once served by through coaches from Waterloo, now has the distinction of being the English holiday resort furthest from the railway network, lying 33 miles from the nearest station, Bodmin Road. The next closest are Barnstaple, 34 miles, and Exeter (St. David's), 55. Since it is not so much further, at 72 miles, a driver with a fast car may take the A39 and A361 to what could be called the West Country's "passenger concentration station" at Sampford Peverell (Tiverton Parkway). Reopening Okehampton, 29 miles away, would still leave Bude much further from the rail system than the place which was once remotest in all of England, Hartland Point.1

To the Sim Harrises of this world, a single main line and a scattering of branches which see no business or first class travel are all the West Country needs and their kind would not be troubled by people in Bude and the great expanse of Mid-Devon and North Cornwall lacking the opportunities and connections that rail transport brings.

To a real transport campaigner, the best place for a "railhead" serving Bude is not Barnstaple or Bodmin or Okehampton; Halwill is not good enough; Holsworthy would not do, either. For Britain to have the public transport it needs to tackle a range of critical issues, and for rail to win dominancy again, the only rightful station for beautiful Bude would be Bude.1

It is typical of a mean metropolitan to dismiss the rail transport campaigners who work in their own time and against the deadweight of authority to promote a great variety of schemes.

There is the spirited and resourceful Olga Taylor who champions Pilning (High Level), a station that the industry cannot be bothered to close or even service with a one-a-day "parliamentary." Read her upbeat submission to the latest organizational review and then the lifeless responses from the usual wet blankets.2

Should there not be a "toy train" waiting at Barnstaple to weave through the hills to Lynton? What is the point in reconnecting the old Ashburton terminus to its branch line? These are two projects supported by this railway and covered on these pages primarily because, even under today's flaccid conditions, they have the potential to provide functional transport.

Just as they have done throughout for disintegrative denationalization, the obedient establishment hacks continue their support for the new London & Birmingham, a 1930s-style economic stimulation project stemming from the 2008 financial crash, and ignore the calls instead for railway development in all areas and extremities of the country.

In his review, Harris refers to some lines on the C.B.T. list as "remarkable railway byways," clearly, in his view, not worth considering.

Admittedly, the report has several inaccuracies. It is fairly obvious that Portishead and Clevedon should have been the Clevedon Branch from Yatton, which had an intensive service until closed in 1966; but Harris takes it to mean the light railway which closed in 1940. Even if C.B.T. had meant the Weston, Clevedon & Portishead, would it be so unthinkable to have back Col. Stephens's charming little line, with its many wayside halts, as a classic electric tramway?

The inclusion of the disused Weymouth Quay branch may seem "rather bizarre" to Harris, but who can say with certainty that Channel Islands sailings will not return to Weymouth one day and that passengers, instead of being herded at airports, again choose to be taken to the quayside in comfort. Or maybe the powers could be taken up by the corporation for a tramway. Its continued existence is only an issue because of heavy motor traffic. This is one of the most interesting lines left, but it does not any more fit with the dreary, destaffed, monofunction system to which the railway has been reduced. Whereas once it was just part of a diverse, penetrative network, the operation of which real railwaymen looked upon as ordinary.

No doubt Harris is a man who as well as proclaiming where the railway should not go, also rules on what it should not do. It is this thinking which has emasculated the railway to such an extent that it can no longer carry its own consumables and equipment; which has every roving manager out on the roads in a staff car; which introduces trains to the West Country that have no space for surfboards; which puts rolling stock on lorries; which transfers traincrew in taxis; and which with the least excuse sends for buses to substitute for trains.

Spurred by a Swedish schoolgirl, Railwatch, the magazine of Railfuture, resorted to stronger language than usual in the July edition.

"We are gradually moving the perception of Railfuture from a bunch of earnest dreamers to an organisation people are increasingly turning to for advice on railway development issues, including reopening proposals, improved services and a better offer to the passenger and the freight customer.

"There is actually nothing wrong with being a dreamer. This can be a strength, not a

weakness, providing we can engage and communicate rational arguments."

"Rail does not seem to grasp the opportunity of producing an energy-efficient, emission-free rail system."

Ian Brown, C.B.E., F.C.I.L.T., Railfuture Policy Director

Even the Editor of Rail Engineer, a free, industry magazine reporting on current projects and technological developments, creditably took it upon himself in September to write to the Transport Secretary pleading the case for rail electrification, a letter headed "The rail industry's contribution to the 2050 net zero greenhouse gas emissions target."3

The minister, until the music starts again, is Grant Shapps, whose attentiveness can only be held for two pages at a time on rail matters; it is not known what limit has been imposed on road lobbyists.

Meanwhile, at the Railsnooze desk, the limp-wristed response to a rail transport campaign is to caution that being too ambitious or demanding may cause ministers and civil servants to take fright, like clucking hens disturbed in the night by a furry intruder. A principal reason that such panic and confusion has sprung from predictions of environmental disaster is because for so long so many people were afraid to voice their concerns and the few who had the solutions were too shy to shout about them.

Harris's final paragraph was the one that sparked a response from here.

"However, putting forward the meandering Teign Valley line between Exeter and Newton Abbot as a candidate, even in the 'later on, maybe' list, seems unlikely to help—and even more unlikely to justify investment, at least in any circumstances we can foresee."

It is only ¾-mile further via the Teign Valley than the main line so there cannot be much of a meander.

That Railnews can foresee no circumstances in which the Teign Valley would be useful is because "we" lack that deep belief and have little imagination.

The railway's letter, which was accompanied by a souvenir mouse mat, was not published. A copy of "A Summary of the Case for Reopening the Inland Railway Route between Exeter and Newton Abbot" was sent to the editor in 2014 and that was also ignored.

The July Railnews carried a one-line letter from a correspondent who wrote: "Bring back the Big Four, that's what I say." The scribe may say the same, but not in so few words. Those leviathans (the L.M.S. was the largest commercial undertaking in the British Empire) did not need outsiders to tell them how to run their businesses or to plead with government in the absence of other representation.

Appendix: Letter to the Editor of Railnews

https://www.connectbude.uk/

https://www.pilningstation.uk/pilning-station-group-submission-to-the-williams-rail-review/

https://www.railengineer.co.uk/2019/08/30/rail-decarbonisation-a-letter-to-the-minister/

Drink-Driving: Still a Laughing Matter

A letter to the Police & Crime Commissioner

There is great disparity between the way in which private and public transport are governed and often it is not understood how this tends naturally to favour the advance of road motoring. There is disparity between self-centred and public road transport, and between road and rail public transport.

Anyone who leaves the relative safety of a railway station and ventures onto roads and streets is immediately struck by the widespread disregard of the law and the lack of common human decency shown by many motorists.

Absolute adherence to the rules on the railway system is built-in and routine. The great body of historic regulation, reinforced today by detailed "safety cases," is overseen internally by an incorruptible chain; it can fail but never be deliberately avoided. A train cancellation or delay may be caused by only a small fault, whose equivalent may be ignored by the private motorist, or even by the bus or haulage operator. A high level of safe practice can give the impression of unreliability or inefficiency. Many people are less appreciative of this determination to preserve human lives than they are of the poorly-paid freelance driver whose tatty, unmarked van tears around dropping their web-order parcels.

Motorized road transport is controlled most of the time by the individual’s sense of right and wrong, which fortunately in civilized men prevents their behaviour from sinking beyond a certain depth. There is only very scarce intervention by police, whose officers are overly stretched dealing with general offending. Although, it has to be said, that, even without the involvement of criminals and uncivilized types, it often seems, especially to the vulnerable road user, as if the law of the jungle is all that prevails.

In the absence of policemen, much of the law is forgotten and a good example of this is the attitude in rural areas to driving under the influence of alcohol, which, much as it was in the 1960s, is still a laughing matter in some circles. And, these days, a young driver is as likely to be doped as drunk.

On this particular subject, in November, 2018, a letter was sent to Alison Hernandez, the Police and Crime Commissioner for Devon and Cornwall. It began by explaining the evolution of the transport modes and how the disparity arose, none of which she was likely to have heard before. It claimed that while development of road vehicles had leapt ahead, a 70-year age gap was still evident in the much lighter application of authority.

"Motorized road transport quickly got ahead of the lawmakers and for all practical purposes remains there today, protected it seems by an institutional resistance to reining in an essential freedom—even if that freedom is but a myth—and by a peculiar, nonsensical human fixation."

The detail of a nearby example of a drink-driving incident was recited. It involved units of three emergency services being deployed, including a helicopter, on a false alarm. No action could be taken against the young tough responsible, when he was found, despite it being known that he had staggered across the car park of a local boozer before over-turning his vehicle three miles down the road.

Whereas the railway has been taken to an extreme of safe practice, arguably restricting the ability to give its best service, drivers of vehicles on a road system that demands more concentration and awareness than ever can legally be under the influence of alcohol, and it is allowed to continue year after year.

"Government … dithers over the alcohol limit for drivers because it is fearful of the effect reducing the tolerance any further would have on pubs, especially those in rural areas; the move could be seen as the killer blow to a perhaps already dying trade. But this overlooks two broad considerations: rural pubs need not be dependent upon motor cars; and nothing should stand in the way of improving road safety."

"Safety legislation has prohibited, slowed or made more expensive activity in every field, sometimes annoyingly or seeming to be unnecessary. The principle holds that no consideration should override the advance of safe practice, even if this denies us other benefits."

Whereas a train driver must not have had a drop of alcohol to drink for many hours before going on duty, a car driver can leave a pub having had a short, early evening session and get behind the wheel almost with impunity.

And if anyone protests that there is no comparison of responsibilities, I would answer that there is just as much, or even a greater, risk attached to flinging a two-ton Barbarian down a dark, wet, winding country lane as there is driving a train guided by rails, with its multiple safeguards.

C.B.

The problem of police strength being too low was understood but it was suggested that only a few examples made of habitual drink-drivers would cause a shock in an area for quite some time, and that, with a little intelligence, it would amount to inexpensive and effective policing.

A prompt, referenced acknowledgement was received in which Mrs. Hernandez advised that a member of her team, the industrious Richard Martin, would respond as soon as possible, certainly within a month.

No more was heard, which is especially disappointing as Mrs. Hernandez is the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners' Lead for Road Safety and, as such, it may be thought that she would be greatly concerned about drink-driving in her predominantly rural area.

A reply need not have commented on the historical position and the example of lawlessness was from 2012. It was not expected that Mrs. Hernandez would say that she was going to urge her officers to pull over more drivers leaving rural pubs on the strength of the railway's letter.

What would have been encouraging is to have heard from Mrs. Hernandez that she and her fellow commissioners were pressing for a long overdue reduction in the blood-alcohol limit for drivers to at least the same level as in Scotland.

Were it not for the great disparity between systems, the blood alcohol level for road vehicle drivers would long ago have been made next to nil, with no tolerance shown to offenders.

Had the truth been out when the letter was written, another quite appalling local incident could have been mentioned, in which two young men died when their Jaggwa collided with another one, causing an innocent man's death in hospital three days later.

"Recording a narrative conclusion, [the coroner] said that [the deceased] had "previously taken cannabis and cocaine" and the car he was a passenger in "was being driven with excess speed" and "on the balance of probability", [the driver] was driving under the influence of drugs."

DevonLive, 4th June, 2019

Appendix: File of correspondence with Alison Hernandez

"You know, more people are dying on our roads than through any serious violence that's happening in our communities, so it is a really important issue. Some of the key things that we’re looking at is to see what we can do, particularly working with the National Police Chiefs’ Council Lead, Anthony Bangham, who definitely believes that enforcement is one of the key areas that we must focus on at the moment. Because through austerity, we believe roads policing teams have lessened, so we need to bring some enforcement back into play."

Watch Alison Hernandez deliver these words, in response to rising road casualties:

http://www.apccs.police.uk/videos/apcc-lead-for-road-safety-alison-hernandez/

In the letter's postscript, Mrs. Hernandez was advised that the letter was part of a campaign and that a copy would be forwarded to Roadpeace, the national charity for road crash victims.

Roadpeace did not at first acknowledge the letter or the enclosed £25 donation. When thanks for the donation came, it did not mention the letter. Sally Howard, the new Administrator, explained that staff changes

had caused a bit of disruption and that the letter had been passed to Amy Aeron-Thomas, Justice and Advocacy Manager, for information, adding: "Thank you again for your support with campaigning and donations."

July, 2019

The foregoing piece was sent, accompanied by a letter, to Mrs. Hernandez in case she wanted to correct or comment upon what had been published.

On 7th August, her assistant, Richard Martin, wired:

The letter, dated 8th January, reached Christow by wire on 7th August, along with the second reply.

Appendix: Further correspondence with Alison Hernandez

It will be left to the reader to decide whether Mrs. Hernandez has even begun to address any of the points made in the railway's letters; or whether, with the number of officers available and the law as it stands, there can be only the vainest attempts to improve conditions on the roads.

In neither of the railway's letters was the vital question asked and in neither of Mrs. Hernandez's letters did she state her position voluntarily, so, to be clear, it was put to her in a closing letter (actually, two questions were put).

She had drawn attention to her force's "Roads Policing Strategy," whose small print on page nine gave a useful pivot.

As England is so out of step with other European countries, and indeed much of the world, in its tolerance of drink-driving, do you support the calls for a reduction in the blood-alcohol limit to at least the same level as in Scotland?

As the "Policing's Road Safety Strategy" states "P. & C.C. to be the leading voice in A.P. & C.C. on road safety to drive change in national policy," will you use your position and influence to lobby government for this reduction in the blood-alcohol limit, so that police advice "don't drink and drive" can become an order?

Mrs. Hernandez replied again at length but the short answers were in effect "no" and "no."

The permitted alcohol limit for car drivers is a glaring irregularity. In all other areas, the law has closed in on unsafe practice yet it is still permissible knowingly to drive a motor car in an unfit, or less than fit, state. It would not be possible in a modern workplace where plant or machinery or vehicles are operated, yet someone whose manner, concentration and reactions are unquestionably affected by even small amounts of alcohol is allowed by law to get behind the wheel of a potentially lethal moving object and set forth on public roads, shared with very vulnerable users, under the influence of quite a large intake of drink.

It is indefensible and talk of extreme offenders being the problem is merely a diversion. It should not matter whether the drinking-driver who stays within the law as it stands causes few accidents, although this should be enough in itself; it is the greater danger that he poses, which any industry risk assessment would rule out in the pursuit of the safest possible conditions.

In her reply, Mrs. Hernandez draws upon some convenient studies done in Scotland since the blood-alcohol limit was reduced in 2014 which cast doubt upon its effect, while ignoring that this limit, or a much lower one, has been in force across Europe and much of the world for many years.

Lowering the limit to 20mg. (of alcohol per 100cc. of blood), which should be the maximum, would mean that police could say with absolute authority: "If you're going to drink, DON'T drive. If you're going to drive, DON'T drink." Instead, the unscientific limit set in 1965 continues to allow drivers to have had "a few." The few - if it is a few - which all recent studies show has such a drastic effect on driving ability.

The roads may be jammed with some of the 40-million vehicles registered to use them, but the country is still far from the saturation point when it comes to the number of drivers, or drivers with the first call upon a car. Yet representation is heavily slanted in drivers' favour; motorists preside over motorists, whose "rights," interests and freedom are paramount in decision-making.

Even in the case of a serious offender, the motoring magistrate will be mindful of the near condemnation depriving another motorist of his licence could entail, such that pleas of hardship and loss often result in leniency. Just as a man will shudder at the thought of another man's balls being cut off, the motorist knows how awful it would be for another poor fellow not being allowed to drive.

The shrieks from motorists and the motoring lobby at the least tightening of control, as if basic human rights were being denied, overlook that driving is a licensable privilege entered into by choice and under what should be strict, enforceable terms.

It can be seen why this fraternity has effectively resisted the change which has swept over every other comparable sphere of activity. Of course there have been great advances in safety and efficiency, mostly for the benefit of the motorist; the closing of the technological gap was acknowledged in the opening paragraphs of the first letter to the commissioner. However, the gap remains often as wide as ever in the relatively light control exerted on the motorist, certainly in practice and arguably with intention.

Measures taken of the full environmental and societal costs of road transport prove how damaging it is in many respects, yet little is done to dampen demand or encourage travel by other modes—or even to discourage travel. Recommended moves in this direction, like road pricing or forms of taxation that shift costs from vehicle ownership to journeys, are routinely ignored. Manufacturers have naturally striven for stronger vehicles as a selling point, but the aim should not have been to make car occupants safer but to make those outside less vulnerable, without segregation.

Possibly the most lamentable of all the failures has been in day-to-day policing, which long ago became too much of a task for ordinary constabularies. There is so little likelihood of rural drink-drivers being pulled over that many have forgotten the law exists, but this is only a part of the broad issue of drivers' fitness, which can be impaired in many other ways.

For there to be any comparison with the safety standards of the modern railway, a dedicated roads police force would be required. This would have to be visible and intrusive, conducting random, roadside checks on vehicle conformity and driver competence. The courts would have to hand down stiff penalties for offences which endanger or cause the loss of life and limb, including a lot more lifetime driving bans in the most serious cases.

The Police and Crime Commissioner for Devon and Cornwall not seeing the need to bring down the blood-alcohol limit for motorists to the level where drink has no appreciable effect on their driving is one of those positions held by people in authority over the years that has helped maintain the 70-year gap, reference to which was used to open the subject in the railway's first letter. While reasoning that a reduction is not necessary, she may as well be a motoring lobbyist, of the type that has always resisted encroaches which spoil enjoyment of the "open road," epitomized by Toad in his gauntlets and goggles. She may do it unconsciously but she does it as well as those who are paid to defend this wretched establishment.

It was thought that Mrs. Hernandez's replies would be of interest to the good people at Brake, the road safety charity, so a letter was sent, along with copies and a £20 donation. They were not acknowledged.

In her reply of 7th August, Mrs. Hernandez proudly advised of the new system which allowed road users to submit evidential film of dangerous driving.

https://operationsnap.devon-cornwall.police.uk/

The railway's utilicon was equipped with a forward-facing camera some years ago. Still images of the worst incidents recorded are kept and shown to people who know the roads.

Some say that a slow vehicle incites dangerous overtaking and intolerant behaviour. The same sort will claim that road safety is improved by increasing speed and that "performance" cars are safer because they can "get you out of trouble." These beliefs and the people that hold them are not worth challenging.