A Little History

The Teign Valley Branch

The Teign Valley branch railway was built in two halves by two companies, with twenty-one years separating the completion of the first half from the second.

The line from Heathfield, situated on the Moretonhampstead Branch, to Teign House Siding (just short of the later site of Christow Station) was built by the Teign Valley Railway and opened in 1882. It followed the river valley for most of its length.

From Christow to a junction with the Great Western main line near St. Thomas in Exeter was completed by the Exeter Railway in 1903. The line left the Teign and fought its way through the hills to reach the Exe Valley.

Both railway companies were formed under different names, reflecting their grander ambitions, but each was to contract and end up with only eight miles of railway, worked together as one line by the G.W.R. and known in later years as the Teign Valley Branch.

The Project

The Exeter & Teign Valley Railway

In 1984, a railway reclamation project was begun in part of the goods yard at Christow, the mid-point and original crossing station on the Teign Valley Branch. This project was really the continuation of one started at Longdown in 1975 by an idealistic 17-year old with a fierce conviction that the railway should not remain derelict. Longdown was given up in 1978 because there was no prospect of being able to purchase the land or secure a long term tenancy.Before the end of the summer in the first year at Christow, the site was cleared of greenery, revealing that the place had in fact been part of a railway, although there was nothing much in evidence above the formation other than the crumbling cattle pen and lines of rotting fence posts.

In 1985, the first length of track was laid where one of Scatter Rock Macadams’ private sidings had been and the following year a covered wagon was delivered to Christow. Work proceeded steadily for years, making the site look like a railway again and collecting materials and equipment, but onlookers could have been forgiven for being ignorant of the purpose, as little indication was given at this stage of what was actually going on.

Railway

Reclamation

on the

Teign Valley

Line

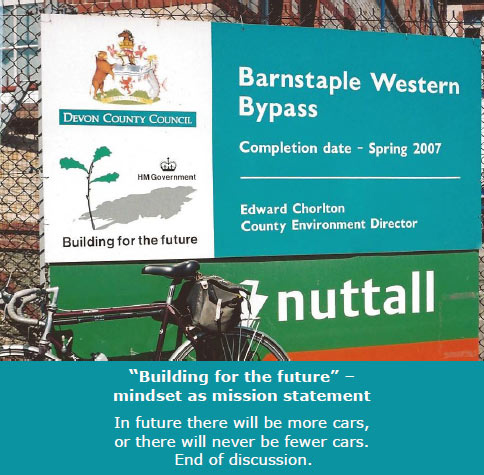

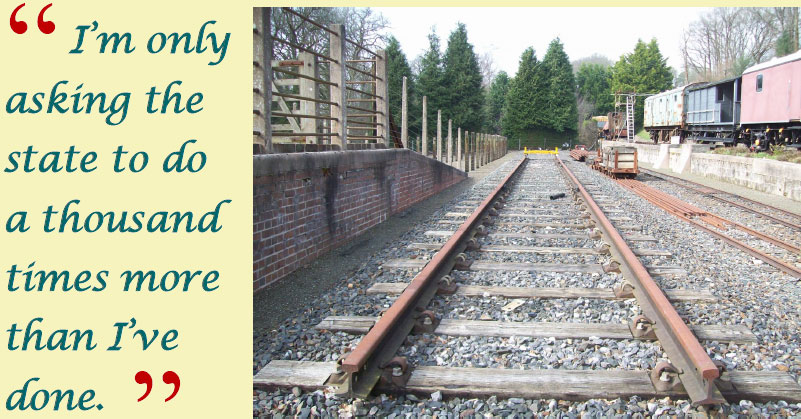

This is what the state should be doing: enabling the return of existing, highly-engineered transport infrastructure from ruin and fitting it for the times ahead; instead of eternally pandering to the lousy road interests, paying obeisance to the god Oil and generally messing up the future.

Perhaps the surest demonstration that the railway had indeed returned was the arrival of a locomotive in 1993. The first diesel ever to reach Christow, Perseus, an 0-4-0 industrial shunting engine, enabled powered movement at the station for the first time since 1960.

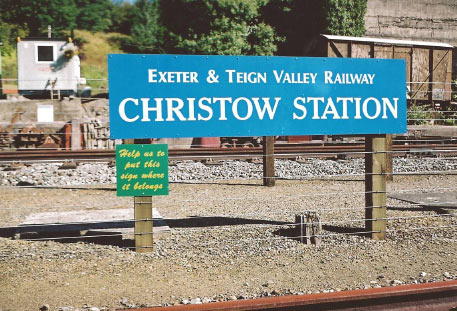

Coinciding with the denationalization of British Railways, in 1995 the project became a small business and the trading name, Exeter & Teign Valley Railway, combining the two former companies’ names, was adopted. In June the same year, the first public open day was held, attracting many people to its blend of "fun, education and interest."

After just a year’s operation, the E. & T.V.R. published its vision of the future, an effort unique among all the railways of Britain. Entitled A Journey in Time, it takes the reader on an imaginary train journey from Christow to Exeter in an age to come. But this is not the story of yet another pickled railway, with men and machines repeatedly enacting moments from some fabled golden era of rail transport. A Journey in Time instead describes a complete public transport undertaking at work and the narrative ranges well beyond the railway in explaining the huge changes which have made the new structure possible. Two branch railways, a network of bus routes radiating from stations and light goods vehicles serving the surrounding country, provide the district of East Dartmoor with a sustainable system of mixed-mode transport; something equally splendid and useful to those who come and go, as it is to those within the company's sphere.

After just a year’s operation, the E. & T.V.R. published its vision of the future, an effort unique among all the railways of Britain. Entitled A Journey in Time, it takes the reader on an imaginary train journey from Christow to Exeter in an age to come. But this is not the story of yet another pickled railway, with men and machines repeatedly enacting moments from some fabled golden era of rail transport. A Journey in Time instead describes a complete public transport undertaking at work and the narrative ranges well beyond the railway in explaining the huge changes which have made the new structure possible. Two branch railways, a network of bus routes radiating from stations and light goods vehicles serving the surrounding country, provide the district of East Dartmoor with a sustainable system of mixed-mode transport; something equally splendid and useful to those who come and go, as it is to those within the company's sphere.

The E. & T.V.R. has made four land purchases, enlarging the site at Christow to about 2½ acres. Nearly 250 yards of standard gauge track have been laid, along with 390 yards of temporary narrow gauge. The loco and rolling stock register lists the diesel shunter, two covered wagons, a goods brake van (in use as camping accommodation), a track recording trolley, a ferryvan, a CCT and a gangcar. Including 26 narrow gauge wagons, road vehicles and boxes, the total weight is 123 tons. Few of these are presentable but most are in running order. Many large and small works of all kinds have been finished and the railway has accumulated a lot of equipment; sufficient in fact to sustain the project for quite some way when at last it breaks out from its present confines, as it must do before much longer.

The railway is occasionally opened to the public during the summer and can be opened specially by arrangement on other days for parties of adults or escorted children. A "Temporary Booking Office" containing an exhibition now enables accessibility, more regular opening and an improved visitor reception >> The Temporary Booking Office >>. Guided walks along sections of the disused line are organized, which serve to introduce people to its scenic beauty as well as its potential. The Building Department trades from its yard at the station, offering a variety of services and, in so doing, helping to establish a reputation of one sort or another for the railway.

There are those, firmly rooted to their bar stools or patio relaxators, who are ever ready to mock the meagre accomplishments of the dedicated railwayman. This probable dislike of the active by the idle is but little removed from the general lack of concern about the extravagance of motorized mass mobility. The era of cheap oil will come to an end, yet most people refuse to contemplate this certainty and authorities attempting to effect even incremental change are therefore often rendered powerless; that is, if they have any inclination to do other than pay lip service to the ideas.

A century ago, men with grit and gumption completed the Teign Valley branch railway—still one of the largest engineering works in the area. Today, along with half the former British railway network, it lies ruined and abandoned. It is dismissed by the petrol sniffers as the transport of yesteryear and the best this feeble generation can suggest is that the line be turned into a cycleway (so as to make the roads safer by removing the slow and vulnerable users). But to do this would really be no better than primitives inheriting some sophisticated device from a higher civilization and then keeping it as an ornament, or for some mundane purpose, because the backward ones haven’t the foggiest idea what it is or how it should be used.

The E. & T.V.R. is sure that its vision of the future will come true and that a revitalized railway system will be the backbone of tomorrow’s transport. Small and insignificant though the E. & T.V.R. is, even after all the years it has taken to develop thus far, in many ways it is in better shape than some fledgling organizations and established companies which lamely hide behind charitable status, have large memberships and receive grants or other outside funding; and yet have no more positive aim than to play choo-choo trains and provide fairground rides.

When the conditions are right, or the right opportunity presents itself, the Exeter & Teign Valley Railway will be incorporated and people will be invited to invest in the "Thinking Man’s Railway." Whether it then succeeds, and is able to press ahead with serious reconstruction, will depend upon enough people being convinced that sinking money into a railway project and being prepared to lose it all is a noble tradition—especially around these parts.

Christow Station Today

The Exeter & Teign Valley Railway is an embryonic reconstruction project occupying part of the goods yard of the disused Christow Station, which nestles beside the river in largely unspoilt Devon countryside.

The project is not a tourist attraction and is nowhere near being able to open to the public like the many places that stuff the leaflet dispensers. At present, the E. & T.V.R. is essentially a little composite which does no more than conjure up a railway atmosphere in a pleasant setting.

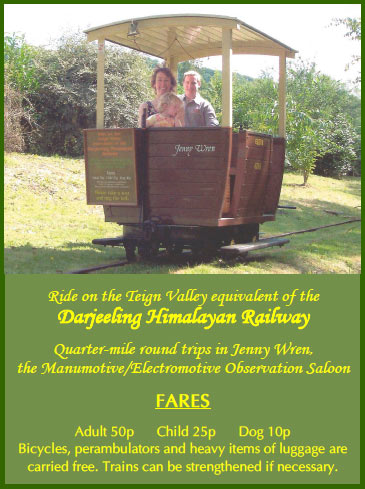

Informal access is permitted upon purchase of a platform ticket and quarter-mile round trips can be enjoyed in Jenny Wren. The railway can be opened specially for parties of adults or escorted children.

The most popular facility is the camping on rail which has attracted a following of its own. People have come to the site from as near as Christow and as far as New Zealand; for some, railway camping has put the Teign Valley on the world map.

Occasional guided walks are organized, which reveal some of the hidden remains of railways and extractive industries.

The railway’s Building Department undertakes a small amount of specialist work for external customers.

Behind the scenes, plotting and scheming continues in an effort to find the means to break out from the confines of the established starting point and commence railway reconstruction in earnest.

By far the meanest contributors to the railway are enthusiasts.

Often, members of the general public, having enjoyed a ride in Jenny Wren or the freedom of the place, or even listened to one man’s rail against the world of cars, are generous almost beyond their means; while those who come to Christow in pursuit of their hobby somehow never find one of the most obvious and interesting fixtures on the site: the Contributions box (an 1898 locomotive tool chest with a painted number).

They may grumble that they don’t get anything for their money, but they do; they would not make a point of coming here if they did not. And if this forms part of their interest, they should be willing to contribute a little towards the upkeep of the place, even if there is not much evidence of expenditure on stock. For, at the very least, it has been kept from the breaker.

In one of the opening scenes of the 1953 Ealing Studios' comedy classic, The Titfield Thunderbolt, the guard of the branch train calls out, "Hey, Charlie! Here's your death warrant," while handing a rolled-up poster to the station master.

After the train has departed, Charlie pastes up the poster and it is revealed to be the closure notice, which soon stirs the villagers to save their line, an adventure whose story is hilariously told in the strangely prophetic film.

The British Transport Commission, an unwieldy body created by the Transport Act of 1947 to direct all forms of inland transport, began to close little-used lines in the early years of nationalization in an effort to stem mounting losses.

Closure notices, like the one at left, first went up in Devon on the branch from Yelverton to Princetown, which was closed completely in 1956. After the Teign Valley closure in 1958, passenger services were withdrawn between Totnes and Ashburton, and in the following year between Newton Abbot and Moretonhampstead.

Beeching's The Reshaping of British Railways, published in 1963, led to a mass execution. Eventually, over 400 route miles and more than 200 stations would be lost from the network of Devon and Cornwall alone. The last Devon closure notice was posted in 1972, when the passenger service between Exeter and Okehampton was withdrawn, all that was left of a main line and its branches which had served Plymouth, Mid-Devon and North Cornwall.

The remnant of the West Country system is today thoroughly diminished in importance and effect, at a time when good sense would dictate a return to rail transport.

Why the railways began to succumb to competition after the end of post-war austerity is no mystery. Car ownership, for instance, promised freedom and convenience that not the best public transport could match. The prospect thrilled even the most intelligent; the extract at right from a government-commissioned report captures the fervour of the time.

Against which, the railways, dirty and old-fashioned, crippled by the loss of their former refined organization and by industrial disputes, slowly and agonizingly trying to modernize, became in the minds of decision-makers a lost cause. They must have concluded that in future only one transport system would be needed.

"We are nourishing at immense cost a monster of great potential destructiveness. And yet we love him dearly. Regarded in its collective aspect as 'the traffic problem' the motor car is clearly a menace which can spoil our civilisation. But translated into terms of the particular vehicle that stands in our garage (or more often nowadays, is parked outside our door, or someone else's door), we regard it as one of our most treasured possessions or dearest ambitions, an immense convenience, an expander of the dimensions of life, an instrument of emancipation, a symbol of the modern age."

Traffic in Towns, H.M.S.O., 1963

Thus began the great transition which attempted to provide for the unlimited demands of road traffic, purposeful and frivolous alike, in the process not just subjugating the railways, but causing the decline of most public transport; even walking and cycling were severely harmed.

In the mad scramble, there was no consideration of the natural or built environment, of human health or of how the new transport would be sustained in the long run. No weight was given to the social and cultural value of public transport. Ignored were the potential benefits of a modernized, high-capacity, general purpose, guided system, with its statutory public service obligation, operating for the most part within its own estate.

Mass motor transport has proved not to be the high plateau of human achievement. Amid the chaotic hell of modern Motopia, with its 35-million vehicles, its vast amount of unnecessary movement, both for people and goods, its death and destruction and division, the wild dreams of the 1960s have been forgotten.

Above anything else, the supremacy of road transport has been built on cheap oil. Yet many countries are now announcing an end to its use as motor fuel. From all directions there is increasing pressure for change. Attitudinal research among young adults points to the declining value and social status attached to car ownership, which has anyway reached its peak in Britain.

The more that automatic guidance, pooling and sharing, road vehicles working in train formation and other futuristic ideas are proposed, the more it sounds like a return to the public transport that was so hastily and foolishly abandoned. And if electricity is to be the new propulsion, it will continue to be most efficiently used by the only vehicles that can collect non-stored power: trains and trams.

Instead of seeing how far the old systems could be shrunk, or aiming for their near destruction, in the 1950s and '60s, the world would have been better as it turns out if public transport had been lifted to new heights, with a highly-developed, fully-extended railway system as its spine. Even with absolute freedom, befitting a democracy, widespread, affordable, inclusive, integrated, multi-modal public transport would have greatly reduced the allure of the self-centred choice.

The stock image of the branch line, a steam locomotive with its short rake of wooden bodied carriages, characterizing antiquity, could today have been a fast, lightweight electric train, possibly fed by energy from an infinite source and running to a rhythmic timetable. Even the smallest stations could have been transport and business hubs, with radiating bus routes and rail-associated services. Passengers could have been making seamless journeys by different modes across land and water using a universal swipe card.

Several branch lines in Cornwall, which escaped the axe, quite recently carried not many more passengers than the Teign Valley trains in their last years. Supported by the taxpayer, these surviving basic lines provide a useful social service, as well as scenic delights for tourists and trippers, and are used by more and more people every year.

But this "third class" designation need not be the pattern. If the individual, instead of fawning upon his car, involved or concerned himself with the community and general mobility, and ensured that his actions supported trains and buses, it would make possible, even in a thinly-populated area, a level of public transport provision hitherto unimaginable.

Don’t know what to do with your city bonus or lottery loot?

Why not help us to put this station sign where it belongs?

Trying to resurrect a railway which the state irresponsibly destroyed is no easy or small task.

Trying to resurrect a railway which the state irresponsibly destroyed is no easy or small task.

Christow Station and a mile of track (10¼ acres) were sold by British Railways in 1963 for £3,000, then roughly a GP’s salary. Today, well over £1 million is needed to buy it all back. This is just one sixteenth of the line—one line of many—and before reconstruction can begin.

But it must not be thought of as impossible, just because a bungalow here and a road incursion there adulterate the course of the railway.

Money sent to the railway produces results; the road interests have after all bought their success. A lot of money would cause obstacles to fall, minds to change and the gathering of a momentum that would lead to the railway system recapturing territory and traffics all over the country.

The E. & T.V.R. is sustained only by revenue and public donations. It needs people who want to see the functional, expansive railway breaking the dependence on oil and the petty mindset of the car, to give money. Those with lots of money they don’t know what to do with here have the chance to make a lasting contribution to the future.

Christow Station is registered as a film location with Creative England, the agency whose task it is to promote the area’s potential to film and television producers.

West Country locations have been used extensively for many years. Near here, Culver, a large "Tudorbethan" house, featured recently in a TV series and Exeter Quay came to prominence in the early 1970s, when tall ships could still navigate the canal, unhindered by the motorway viaduct.

One of the most frequented locations is Staverton, a station on the Ashburton Branch, the rump of which today is a hermitage railway.

But producers do not always want staged action; often all that is needed is a static backdrop for scenic accuracy or atmosphere.

The industrial or rustic narrow gauge and the camping vans at Christow are unique. When pictures of the small brake van, Tadpole, were submitted to the agency, it was suggested that an imaginative children’s story teller at the Beeb could weave a whole series around the new prop. Perhaps a script should have been sent as well. (Does the railway have to do everything?)

One small connection with the world of film is the mine truck at Christow which was borrowed by Spielberg and featured in the chase sequence where Indiana Jones and his chums make their escape from the Temple of Doom. Or so wide-eyed children are led to believe.

The location has never actually been filmed but enquiries have been made about using it as a set for a fashion shoot. And it has been used by first aiders in an exercise dealing with a casualty beneath a locomotive.

www.creativeengland.co.ukSome of the Thinking Behind the Project

>> Transport for When the Party's Over >>

>> Championing the Railway Industry >>

>> An Alternative Route >>

More Thoughts and Observations

>> Is the Globe Warming? >>

>> Other Transport instead of Other Fuels >>

>> Nightstar >>

>> Thanks for all you have done >>

>> I'm only asking... >>

>> Bats >>

>> Causeland and Christow >>

>> All the Stations in Devon, Cornwall and Somerset >>

>> The Fancy Bridge Competition — Modern-Day Follies >>

>> The Launceston Branch and Walkham Viaduct >>

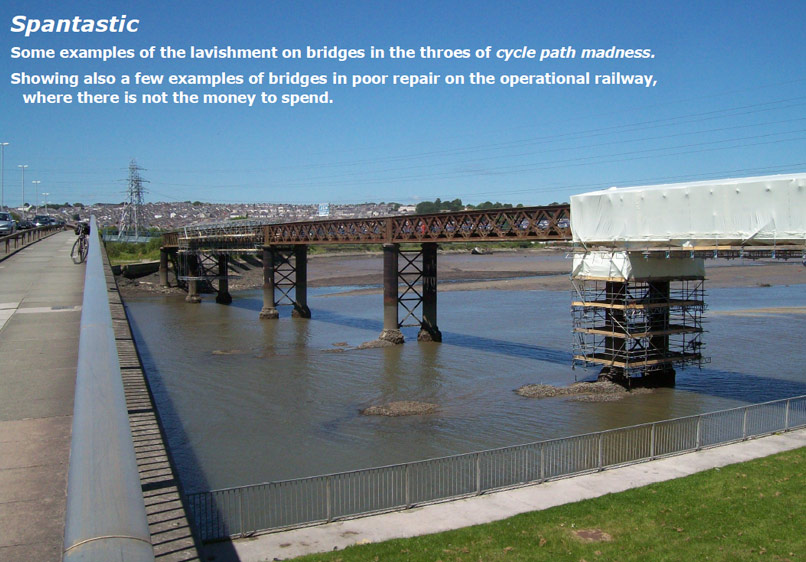

>> Spantastic >>

>> Transport for the High Achiever >>

>> Clarksons >>

>> Gallery of Stupid >>

Some of the Thinking Behind the Project

Transport for When the Party's Over

Fifty years after the withdrawal of passenger services from the Teign Valley Branch, it is easy to believe that its story came to a close, if not in 1958, then with the later dismantling of the line almost in its entirety. As evidence of the branch disappears bit by bit, and with many busier routes since lost from the national network and the railways of Britain still largely in decline, there would seem not the remotest possibility that another volume of history could ever be written about the Teign Valley line.Yet there is a growing school of thought that reckons a series of events is looming which will shatter the developed world’s reliance upon oil and rudely awaken people to the dangers of extravagant consumption of all resources. The notion is that many systems which cause less impact and which are more frugal in the use of energy—but which are still today generally mocked by a complacent society—will soon have to be rehabilitated.

Because some of the worst excesses occur in the realm of transport, this is bound to be affected by great upheaval. Much of what is now considered sacrosanct will be torn asunder and much that is now ignored, or held up as impracticable, will come to the fore. Particularly, it will be realized that there has been a vast underestimation of the capacity of public transport—buses, trams and trains—to provide an acceptable and viable alternative to the unsustainable shambles propagated by government for much of the last century.

Despite the promise of change, society is still moving uncontrollably in the wrong direction, at a time when any excuses it could once have used are worthless. Road transport carries on leading its charmed existence, even when it is seen to be taking its toll on the environment, on human health and temper, and on the fabric of society.

The sensible course now would be to invest in a long-lasting solution: a well-engineered, integrated public transport system with a complete modern railway network as its backbone. This would give the most freedom and genuine mobility to everyone, and would prove the most effective means of shifting freight, yet would have much less impact than the grossly-damaging dependence on private cars and heavy lorries.

The familiarity with public transport which was once universal is now uncommon, and to a great many people transport is solely cars and trucks; walking and cycling do not even figure. The same view is entrenched also with the authorities, though they will protest that this is untrue.

If visitors to Christow Station leave with a better understanding of the railway—even some sympathy for this relegated mode of transport—then its efforts will have been worthwhile and visitors will have grasped something of the serious intention behind the project.

Championing the Railway Industry

The railway was Britain’s gift to the world. At one time, railways were more developed here than anywhere else, yet now it seems that Britain values them the least. Many other countries understand the railway’s strengths and fully exploit them; here, it is their weaknesses that are played upon and an institutionalized ignorance prevails.This is in no small part due to the shortage of champions the railway has had in the last sixty years. Those stalwarts it has had have been opposed by numerous powerful organizations standing to gain from ever more use of road transport. And government has meekly pandered to the strongest lobbying. However, the situation is changing. Not because these organizations have shut up, but because many more individuals are now concerned about the effects of road traffic growth and authority has been forced to make some half-hearted attempt to slow the trend.

It is so long since the railways were cut back that a generation has grown up without knowing about the work the railways once did, or about how extensive the system once was. Those who still rue the closure programme have been joined by younger people who feel that the railway should have a vastly expanded role today. But, in a country that has mostly forgotten about railways, where can they find support for this view?

Well, there is an outstation in the Teign Valley where the idea of a railway renascence is subscribed to in no uncertain terms. At Christow, visitors are presented with a mixture of the practical and theoretical which makes clear the railway’s capabilities, as well as its limitations. Looking ahead, rather than leaving the railway confined to a particular niche in history, the case for modern rail transport is presented in a novel and challenging form. Any visitor with an open mind should at least take away some food for thought.

An Alternative Route

This is the Paddington to Penzance, Great Western main line, as seen from Langstone Rock on the 5th February, 2014, looking towards Dawlish.On this day, the line was closed because of extensive damage, including a massive breach of the sea wall and washout of material putting houses in Riviera Terrace, Dawlish, in danger of collapse. At the time of writing (9.2.14), it was estimated that repairs would take six weeks and cost £10-million.

The line reopened to traffic on 4th April, after a blockade lasting 59 days. Repairs were estimated to have cost £35-million. £16-million compensation was to be paid to train operators. The total cost of the disruption could only be guessed.

Formerly, there were two diversionary routes available: the Teign Valley and Moretonhampstead branches, via Christow and Heathfield, until 1958; and the London & South Western’s main line via Okehampton and Tavistock, until 1968.

Generations of holidaymakers, bound for Great Western resorts and full of anticipation for their first glimpse of the sea, redolent of the week to come, have been awed as their train swept past this point and the land fell away from the carriage windows. Even regular travellers are perpetually fascinated by the changing behaviour of the sea in all weathers, seasons and states of the tide.

Generations of holidaymakers, bound for Great Western resorts and full of anticipation for their first glimpse of the sea, redolent of the week to come, have been awed as their train swept past this point and the land fell away from the carriage windows. Even regular travellers are perpetually fascinated by the changing behaviour of the sea in all weathers, seasons and states of the tide.

From here to Teignmouth—three miles, not counting the shelter of the tunnels—the line is above the beach and below the cliffs. It is one of the most scenic stretches in the country and one of the most vulnerable.

Network Rail spends around £500,000 a year on maintaining the defensive, retaining wall. Except where rebuilt, it is the original 1846 masonry structure, not less than two feet thick, founded in the soft bedrock, often only just beneath the sand cover. Behind the wall is fill, readily washed out when there is a breach.

If the sandspit at Dawlish Warren, behind the camera, were to be greatly reduced—a process which is going on—then the line alongside the Exe estuary at Starcross would be exposed to the full force of the sea.

Throw a violent sou'easterly and a spring tide at it; raise the mean sea level; wash the cliffs down as well. What would be the effect of a catastrophic severing of the line?

Such is the diminished role of the railway today, the small percentage of passenger traffic and negligible freight it carries could easily be accommodated on the road system. And might it not then just as well stay there? Serpell put if forward as an option thirty years ago: a national network which went no further west than Exeter.

That is not going to happen. In time, the railway will reverse the present situation and become again the dominant mode. When it does, it will be essential that there is always an alternative to a vulnerable route.

Taken from Langstone Rock on 12th January, 1996. On this day, the Down line was closed because of damage between Dawlish and Teignmouth, and only some trains were using the bi-directional Up line. The service was disrupted for several days on this occasion. The Parson and Clerk can be seen to the extreme left.

More Thoughts and Observations

Is the Globe Warming?

No, of course it’s not. It simply cannot be. Not in the way and to the degree that is being pushed like there's no tomorrow in all the news media. It is complete bunkum. It has not a shred of scientific standing. This can be said with certainty because if there were any truth on the global warming bandwagon every man jack would by now have girded himself for action, with the same urgency that other forms of danger provoke, like fire licking his heels or a tidal wave approaching.

This can be said with certainty because if there were any truth on the global warming bandwagon every man jack would by now have girded himself for action, with the same urgency that other forms of danger provoke, like fire licking his heels or a tidal wave approaching.

Even people in a lost valley would be clamouring to know how they could do their bit to change; how they could help reverse all the wasteful, damaging and disintegrative trends of the last 50 or 60 years. The cries would go up: "We need more things made locally" and "Access not mobility!" A bright spark would offer: "We need a community based on economic interdependence." The coalman would ejaculate: "Down with oil!" The village idiot would pipe up: "Let's reopen the railway!"

Even people in a lost valley would be clamouring to know how they could do their bit to change; how they could help reverse all the wasteful, damaging and disintegrative trends of the last 50 or 60 years. The cries would go up: "We need more things made locally" and "Access not mobility!" A bright spark would offer: "We need a community based on economic interdependence." The coalman would ejaculate: "Down with oil!" The village idiot would pipe up: "Let's reopen the railway!"

Instead there is silence and an observer could be forgiven for concluding that the lost valley's answer to global environmental problems is bigger cars and more of them, for this is the pitiful reality.

The layman cannot check the scientific reasoning. He can doubt, not whether modern man has had the power to bugger the planet, but whether he can now measure his influence, given that his whole existence has been so short. The layman can also question why the issue has only recently been taken up and why, despite the hysteria, nothing of any consequence has been done or looks near to happening.

"A rail network capable of operating without dependency on oil would seem a necessity for this time. In the face of this one over-riding consideration—that there should be a transport network which could service the whole country in the case of interruption of oil supplies—there is an unanswerable case for the electrification of all but the most lightly-used branch lines.

"The point about such a decision is that it plays safe with the country’s future. If those optimists who still deny any possibility of oil scarcities are right there will be no waste of oil; we will be able to burn it in the power stations to power an electrified network. If the pessimists (who call themselves realists) are right, there is going to be nothing we can do with our diesel locomotives in the absence of fuel to drive them. A fully-electrified rail network in the end is a question of national security.

Environmental campaigning is often unfairly tarnished by the negative assumption that what is being promulgated always involves stepping back, going without, having fewer conveniences; or being colder, hungrier, less empowered, etc. If the threat of global warming or climate change or peak oil—whatever the frightener—were to be treated positively as an opportunity for a massive awakening to modern follies such as oil dependency and globalization, then the search for different ways of continuing much of what is done today—for having much of what is had today—could be portrayed as hugely interesting and satisfying—great fun, even. The challenges of establishing a more self-contained community—of working out ways to share and co-operate, to reduce the need to travel, to generate power locally and much else—should be seen as infinitely better than wallowing in a rut of gross over-consumption and fuel denial.

The great thing is, all that it is said needs to be done to avert or minimize global warming is surely worth doing anyway and long overdue. If in the centuries to come—barring flood, tempest, pestilence, volcanic eruptions or other shit—today’s precautionary actions were found not to have made a scrap of difference to the climate, then the upheaval will have been justified alone for the new, better direction that was found.

Other Transport instead of Other Fuels

So where are the tub-thumping railwaymen?

Any discussion about sustainability must touch on why transport has become so unsustainable. And it would have to be questioned why the most complete railway system in the world, which held the potential to be developed into the fully-electrified nucleus of the nation's public transport, has been very largely destroyed and put out of focus in the eyes of the majority.Beware the attraction of the new and the danger of the false promise. People grew tired of an established system, seeing only its faults, and flocked towards that which at first offered so much, seeing only its advantages. How many driving off in their first car had any idea that they had bought a living statistic which would be catered for in all sorts of ways, not least by the expansion of the road system to meet forecasted demand? How many knew that their choice would eventually lead to the deterioration, and often the collapse, of the transport which had been open to all?

You continue to believe that you’ve bought the most liberating tool ever known to man when the thing is getting you nowhere and is making you poor, unfit and downright miserable.

Car advertisers still portray free-spirited drivers flinging their steeds around the curves of an open road or canny ones running deserted back streets; when everyone knows that the awful reality of motoring involves daily death and injury, jams, environmental degradation and a general dehumanization. Even the obvious health and social consequences of sedentary lifestyles and corralled children actually lead to more car sales.

But after the War (if not earlier, inspired by the Third Reich), government too had embarked on a policy of enabling mass, motorized mobility. If it was not intended that public transport should wither away as part of this drive to modernity – the evidence in fact points to such an accepted outcome – the result undoubtedly has been a huge loss of capacity; the greatest being with the railway, which now operates over half its former network with only "pipeline" and "conveyor belt" freight remaining from its comprehensive array of ancillary services.

It soon became clear that a juggernaut had been set in motion. The growth in car ownership and road freight demanded more roads. Not just the new arterials were built: ancient street patterns in towns and cities were bulldozed, to be followed by North American urban sprawl capable of being serviced only by cars and trucks. New roads filled up and the process continued, as if by accident.

However, there was nothing accidental in the promotion of road transport; its ascendancy has to be linked to the power of vested interests. The railway industry lost its political clout, if not at the outbreak of war in 1939, then certainly with nationalization in 1948. On the other hand, the interests that gain from road use are still among the most powerful and well placed in the land: oil, construction and motor manufacturing. Smaller fry like the motoring and road freight organizations lobby as one of their primary functions.

Only one road-rescue service, the Environmental Transport Association, lobbies for better transport, not for the car. Yet how many motorists know (or care) that their membership fee is partly a subscription to a lobby group? Most are happy to think that the massive expansion that has occurred over the years has just been normal human progress, aided by governments letting people have what they wanted.

If blame is to be attached, it would be easiest to say that the railway was brought down by its own inability to modernize and adapt; by its management, by its idle, unmotivated staff, etc. Lame accusations are still made today, as if the muddled constituents of the denationalized railway were not utterly at the mercy of political forces.

What almost complete dependence on road transport over so many years has done is entrench a belief that the system is untouchable; even meagre efforts to slow its rate of growth have been scrapped. Long enough has passed for politicians, planners and the man in the street, who can remember or imagine nothing else, to think of the structure as everlasting. Yet because of the sheer extravagance of its energy and material consumption, it must be the most prone to collapse.

Even those who care, when reminded that the railway has slipped from view, respond resignedly by saying that it is not possible to resurrect the former far-flung network for too much has been lost; as if all the shoddy development and road schemes that have littered closed routes should stand in the way of railway reinstatement, when nothing – priceless landscapes, settled communities or deeply felt protest – has prevented the construction of 60,000 miles of road.

People should not be cowed into excluding options for the future because of their seeming out of reach. The ideas need propagation and explanation. Folk should agitate for a modern, electrified national railway system run by zealous operators freed from the straightjacket of state control. The crapspeak of the road lobby should be countered at every opportunity.

"We want our railway back!" should be the cry, adding, "We cannot ignore the inherent advantages of rail: its free-running trains that can use any fuel and its highly-engineered routes. We should get as much traffic as possible of all kinds off the roads and onto an efficient, co-ordinated, spinal transport system."

Authority must be repeatedly challenged over its actions. Most of what is dressed up as worthwhile change is mere tinkering and leaves the established order well alone. Opening of cycleways, for example, wins councils green points, but letting the motorist think that he does not have to watch for exposed road users – or worse, letting him think that they no longer have any right to use the roads – serves the likes of Clarkson more than any sustain-able transport agenda.

Authority must be repeatedly challenged over its actions. Most of what is dressed up as worthwhile change is mere tinkering and leaves the established order well alone. Opening of cycleways, for example, wins councils green points, but letting the motorist think that he does not have to watch for exposed road users – or worse, letting him think that they no longer have any right to use the roads – serves the likes of Clarkson more than any sustain-able transport agenda.

The lavish, grand design, road construction programme continues, with major schemes being promoted by Devon councils using heavily slanted cost-benefit analysis. Railway retrenchment also continues as those same councils stand idly by and refuse even to apply their own tame, unambitious policies. Corridors for new roads are kept open for decades, while closed railways are obliterated. Beneath the surface, it is really business as usual.

The search is always to find other fuels to perpetuate what has had so much invested in it, when the best brains should be working to extricate the world from this fix and begin a massive transition to other systems. These would not have to replicate present modes because sweeping change across the board would reduce the need for people and things to move so far and so fast, as well as dealing with other modern excesses. It might be found that many new ideas bore a striking resemblance to the way things used to be done.

Almost everyone I speak to, who I think should know, claims not to remember Nightstar, the system of through services which was intended to connect the outer reaches of Britain with continental destinations after the opening of the Channel Tunnel.

The most lavish fleet rolling stock ever built was turned out of B.R. Engineering factories; the price tag in the early 90s — £1-million a coach — certainly smacks of high spec. If I remember correctly, the trains were described as hotels on wheels. I think that they had a restaurant, café and shop, as well as the sleeping accommodation. And a first for B.R. was that the "day" coaches had airline-style, reclining seats, so budget travellers could make a long journey in greater comfort. The Electric Train Heating Index (a measure of the demand on the train power supply) was greater than any other coach. A maintenance shed was built at Laira (Plymouth) for the West Country service: Plymouth to Paris/Brussels/Berlin/Milan – wherever.

Then, suddenly, as denationalization approached, B.R./government announced that the market for the services had been misjudged; it did not exist. A bit like, "There are no weapons of mass destruction." So, just a slight miscalculation, then. Unlike the "dodgy dossier," no mention was made of the research that must have been done to merit the investment.

The Nightstar stock, never used, was stored in secure military sidings, away from the public gaze and eventually sold abroad. And now, it seems, the whole project has been virtually forgotten.

Forced into competing with cheap flights, the European railways have built high-speed routes, now even reaching London. A traditional railwayman may marvel at the capacity of 19th-century technology to win against the new, at wagon wheels holding the rails at a speed which shows no sign of being the limit, but this must be tempered by the acceptance of grand vitesse train travel being as much of an environmental nuisance as motor routes and airports. The security-fenced lines are nearly as intrusive as roads. They are not general purpose; they are duplicate; they serve far fewer communities directly; and the trains, in overcoming huge wind resistance, consume much more power than those that run at half the speed. The fact that in France the trains are effectively nuclear somehow does nothing for the environmental case. If, in competing, railways become as bad as air and road, then it is a competition that should never have been set up.

A future in which there is energy conservation and less flittering travel must have trains that are not as hurried, but ones that are reliable and comfortable, and which enable the journey to be savoured. It was this very concept that was abandoned at the break-up of B.R.

C.B.

The shed at Laira Depot in Plymouth was extended to provide space for maintaining the West Country Nightstar stock.

Seen at left of the building, today the extension is Road 10, used for maintenance of H.S.T. sets.

"Thanks for all you have done"

Wasn't this what the demob officer said to men collecting their papers?"The fact that the railways were built and maintained by various separate private enterprises to meet actual or anticipated traffics provided this country with many alternative routes. This would not have been the position had there been a concentrated system without alternatives and without a variety of stations in large cities and towns. The widespread network of the railways with 37,000 miles of running lines, making with the many sidings a total track of 51,000 miles, has proved its value."

Facts about British Railways in Wartime,

The British Railways Press Office, 1943.

The Reshaping of British Railways, Part 1,

Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1963.

Along with, "The Teign Valley: the practical railwayman's preference," the quote above was coined in 2014 after the sea wall had been breached at Dawlish.

Rather like the utterance of a politician, no thought was given to this when it first came out in conversation. But a moment's calculation proved that it was very nearly true.

In fact, this symbolic length of track is greater than one thousandth part of the Teign Valley Branch. To re-lay a single line from the toe of the points at the main line junction in Exeter to the buffer stop in the bay platform at Heathfield, seven chains short of 16 miles, would actually need 935 lengths of track equal in length to this one.

While this claim is undeniably a great simplification of what is entailed in railway reconstruction, it does somewhat demystify a part of the physical task.

This section of the Up Main at Christow may not be of any use, but it is real and its installation involved the same effort as laying new material would have done.

And, as can be seen, this short token track is not all that has been done here.

Bats

Simply being critical of bats today carries the same penalty as did insulting a Chelsea Pensioner under "The Bloody Code." Not quite, perhaps, but it is no less than transportation with hard labour—if a penal colony can be found which has not been ruined by development.

So this piece is not going to criticize bats and the wonderful, winged creatures are merely being used here to raise an example of the modern practice of "offsetting" harm to flora and fauna.

The title of course has another meaning, as in the archaic expression, "bats in the belfry".

It is possible not to do something harmful or go without something damaging. By a clever stroke, however, harm or damage can be "offset;" that is doing a bit of good to mask a lot of bad. Carbon offsetting was briefly the fashionable confessional. Fly to an exotic island for some sun in a jet aircraft with 40,000 gallon fuel tanks; plant some trees to offset the damage. Another kind of offsetting allows buying a tank instead of a car as long as some cash is sent to a wildlife fund. The massive intrusion of a new road can be offset by capturing some members of an endangered species and rehoming them, or by digging up some pristine soil and spreading it elsewhere.

It is all meant to give the pretence of balance when really it is utterly useless and meaningless, like the conscience-salving of those whose claimed unease at environmental destruction is not going to stop them having a good time. Nowhere is it understood that if modern civilization reined in its rapacious demands and curtailed its devastating impact, resources would last longer—even indefinitely—mankind would find itself relatively at peace with its surroundings and nature would happily take care of itself.

All this would not be such crap if the consideration given to the natural kingdom were extended to human existence, for it does seem sometimes that people can be disregarded.

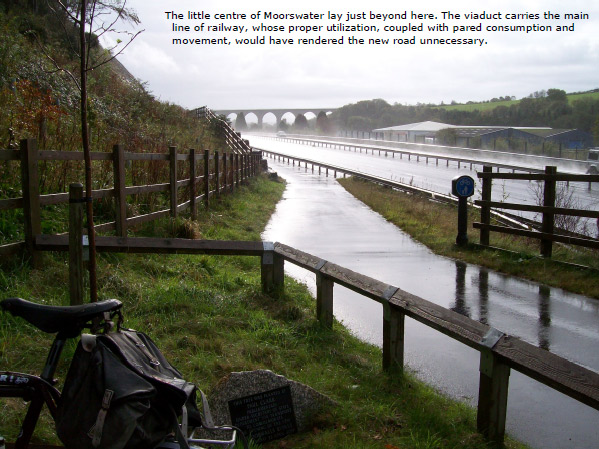

On the Dobwalls Bypass, between Dobwalls and Liskeard, is a strange structure spanning both the old A38 and the new dual carriageway, probably unnoticed by the majority of road users, or taken to be power lines.

It is one of two bat passes, designed to guide bats whose regular foraging routes have been disrupted by the expanse of new road. The £300,000 structures were a condition imposed by a wildlife body as a "mitigation" measure.

To suggest that the thing is based on quack science would be to question its value, which is not the purpose here. What is asked is: if the bats’ ancestral habitat was important, why was a human settlement deemed expendable?

For just along the road lies what is left of Moorswater, a hamlet on the edge of Liskeard. The main road used to pass through it. The place grew when the Liskeard & Looe Union Canal was opened and limestone and sand, coal and culm, was landed at the Moorswater basin. The Liskeard & Caradon Railway, built to bring stone and ores from Bodmin Moor, had a terminus here, firstly connecting with the canal and latterly with the railway to Looe which replaced the canal. Remarkably, the railway is still in use, although the old station, locomotive and carriage sheds, and the line to Caradon have long gone.

On Canal Road coming down from the town was the Commercial Inn, Methodist chapel and a little cluster of homes. That was until 2008, when the place was obliterated by the new £50-million dual carriageway, a monstrous scar on the landscape. What is left is still called Moorswater, but its heart has gone.

Why, in the scramble to speed everything on its way, was such importance attached to the home of the bats, but none to this human place?

For another example of "offsetting" see: >> The Sultans of Spin >>

Causeland and Christow

The Arbitrary Nature of the Closures

The Looe Branch (Liskeard to Looe) was condemned to outright closure in the 1963 The Reshaping of British Railways. The line came within weeks of execution in 1966, but it was stayed because of the difficulties of providing a replacement bus service along the narrow lanes.

The line now receives a government subsidy equal to its deficit and is heavily promoted by an outside partnership body. It carries over 100,000 passengers a year.

The Teign Valley Branch (Exeter to Heathfield) was closed to passengers in 1958, the work of the shadowy Branchline (later Unremunerative Railway Services) Committee. Though a short length in Exeter still serves a scrap metal yard, most of the remainder closed completely in 1968. Christow was cut off after flood damage in October, 1960, but was not officially closed until May, 1961.

The line carried 60,000 passengers in its last year.

Causeland

It would be easy to assume that the service at this intermediate halt on the former Great Western branch line from Liskeard to Looe is worse today than it was once; it is surely triumph enough that the little stopping place remains at all.

But, in fact, ignoring for a moment the wretched state of the track (although safe, it has to be said) and the fate of the system beyond here—including the emasculated seaside terminus—the service and provision at Causeland, and the other two halts between Coombe Junction and Looe, St. Keyne and Sandplace, is arguably better than it has ever been.

Although the diesel trains take longer than steam—partly because there is no signal box at Coombe Junction, where trains must reverse—there are more of them, even if they have to be requested to stop. And they run on Sundays in the summer, which is better than the Great Western service but not as good as early B.R. operation. Also, it is likely that fares are cheaper in real terms today.

The three halts never offered any other service: they are listed in the Railway Clearing House "Hand-Book of Stations" as "P*" —passenger only. There are no demolished offices and goods sheds and no lifted sidings (except for the one at Sandplace). The essentials are still there: a well maintained platform, waiting shelter and up-to-date timetable; no less than would have been provided.

But today, after dark, instead of a single hurricane lamp picked up by the guard on the last train, the halt and its approach are brilliantly lit by electricity. There is a ―Help Point‖ at which information can be obtained and emergency assistance summoned. There are even payphones at some places. And is that not a security camera atop the galvanized standard?

The maintenance obligation is considerable. Someone comes by road to inspect the station, sweep the platform, change the posters and timetables and empty the bin. Another person comes to service the Help Point and another to check the electric lights.

And it is used by about a dozen passengers a day.

Christow

The very arbitrary nature of the closures means that today an area poorly served by public transport and with a population much higher than that between Liskeard and Looe has only the ruins of a branch line and has not seen a passenger train for more than fifty years.

Causeland sees up to 24 trains a day; Christow has nothing.

And under present twisted conditions, in which the legislative and regulatory burden, the lack of proper organization and political influence, and the failure to gauge the future combine to make the physical obstacles the least of the task, reconstruction of what was so casually destroyed would take

a Herculean effort.

Coombe Junction sits at the foot of the tortuous descent from Liskeard, the line that connected the little Looe & Caradon system to the network in 1901. The halt lies just beyond the junction itself, on the line towards Moorswater, and trains serving it must move from the reversing point. The service is effectively "parliamentary;" that is, as long as the station is open, a service must be provided. This obligation is met by two successive trains each way on weekday mornings, which are practically useless.

Even so, the place is fully maintained, if not to the same standard as the other stopping places. In fact, much of the platform has recently been rebuilt after being affected by subsidence; work presumably paid for by a third party’s insurer.

for by a third party’s insurer.Causeland is the busiest of the halts. Coombe Junction sees only about one passenger a week, but its usage is still fifth from the bottom on the national network.

In 2012, the railway wrote to the Devon & Cornwall Rail Partnership suggesting a way that more trains could serve Coombe Junction without adding to journey times, and offering to leaflet the area in an effort to get some families to take at least an occasional jaunt to the seaside from their local halt. It was merely proposed as an exercise to see if takings could be increased by a short, concentrated push.

The letter went unanswered and so did the subsequent one offering to make a generous donation to the work of the partnership.

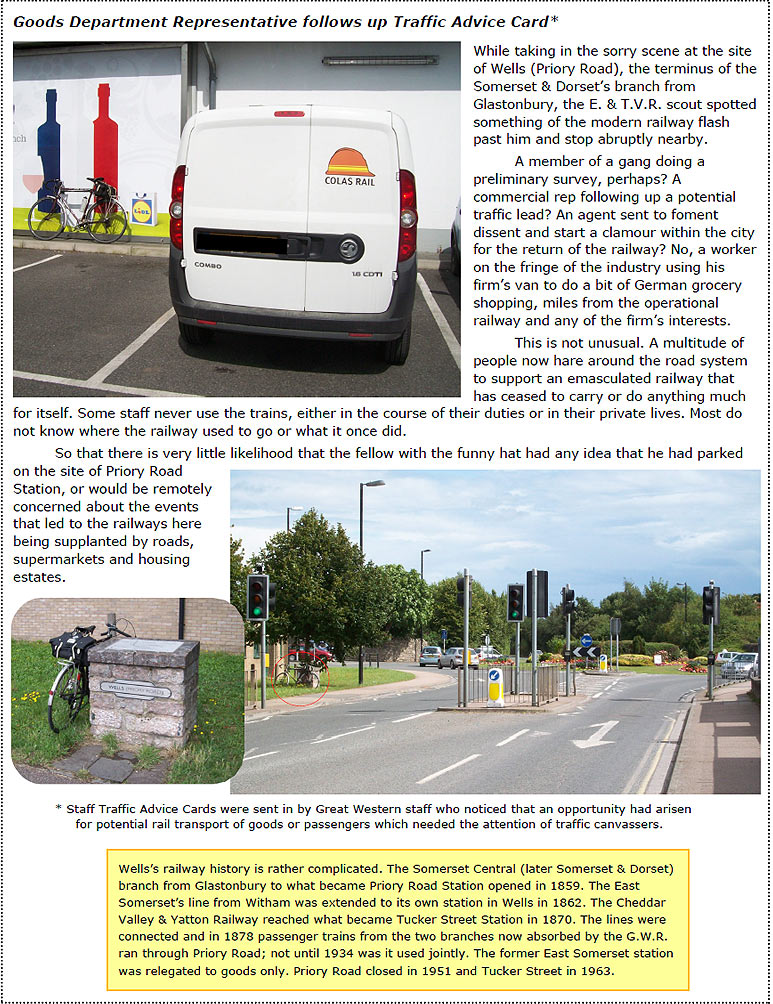

All the Stations in Devon, Cornwall and Somerset

There will be some, but not a great many, who can lay claim to visiting every one of the 492 stations or station sites in Devon, Cornwall and Somerset. There are 104 stations open today.

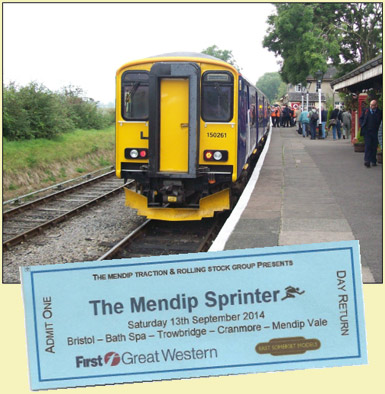

As from 13th September, 2014, the E. & T.V.R. scout can join the little club's informal membership.

However, what may distinguish the railway's scout from the rest is that he has used* every one of the operational stations and visited the vast majority of the closed stations on his bicycle.

The last one, Wanstrow, was ticked off in style. The scout had cycled from Castle Cary to Cranmore with the intention of spending some time there before riding on to Merehead, Wanstrow, Bruton and a few points on the S. & D. between Evercreech Junction and Cole.

Not long after arriving at Cranmore, to his surprise—this being a pickled railway—a Class 150 D.M.U. pulled in and emptied its load of passengers. Enquiries quickly revealed that this was a special excursion from Bristol. Rare? Well, there hadn't been one for three years.

The day's plan was altered. After a trip nearly all the way to Shepton Mallet on the East Somerset's old D.M.U., a thorough inspection of the station and sheds, and a spot of lunch, the scout cycled over to Merehead (properly Torr Works Quarry) to see the rail terminal and find a place to view the biggest man- made hole in Europe, getting back to Cranmore for the 1615 return Crankex.

The site of Wanstrow, the final station in the county, was observed from the carriage window and the railway's scout and his Raleigh were put off at Trowbridge, the county town of Wiltshire.

* Entrained or detrained, having been, or going, somewhere else, not simply having put a foot on the platform.

>> Stations in Devon >>

>> Stations in Cornwall >>

>> Stations in Somerset >>

>> Stations in Dorset >>

July, 2022: Nearly eight years after ticking off Wanstrow in Somerset, the scout stopped at Daggons Road, the last station on the Dorset list. He can now claim to have visited all 553 stations or station sites in the four counties of the West Country.

The ride that included four old stations in Dorset, two in Hampshire and one in Wiltshire, is described on the Scouting pages.

If every station were to be given a numerical classification according to the transport services and accommodation it once offered, the loss to the three counties would be far worse than a simple 77%.

Under a weighting system, an unstaffed halt serving passengers only would be classed as a one, while a major station may be rated at ten or more.

Since every one of the stations remaining today serves passengers only, the figure would still be 104, whereas the total valuation would once have been many thousands.

Some idea of the effort put in to an exploration of 43 miles of ruined railway and its dozen former stations may be had from this "route refresher" of the Devon & Somerset Railway, the Great Western's Barnstaple Branch from Taunton.

And another one...

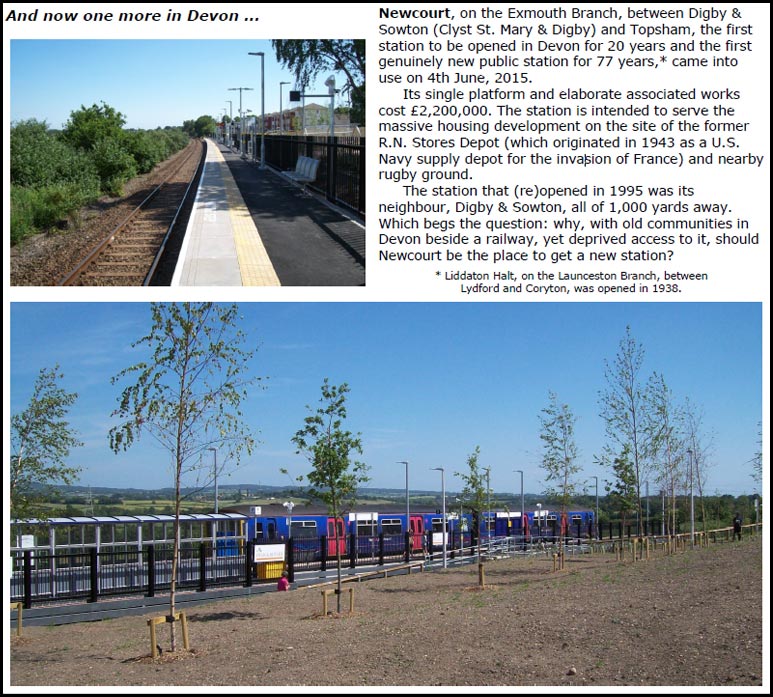

Part of the "eco" box-ticking exercise for the ghastly urban overspill at Cranbrook, "Greater Exeter," was a railway station. Like Digby & Sowton and Newcourt, Crapbrook was partly funded by the housing developers. And like Newcourt, opened last year, Cranbrook was beset with difficulties which delayed its opening and raised its costs. The £5-million "park and ride" (for why else would it have a 150-space car park?) station opened on 13th December, 2015.

There had been talk of reopening Broad Clyst (closed on 7th March, 1966), three-quarters of a mile to the west, but it was decided instead to site a station near the first of Devon's new towns, originally referred to as Clyst Hayes.

Construction of the single platform halt took well over a year. From receiving its act in 1856 to opening the line from Yeovil to Exeter took the London & South Western only four years.

What can be said about Crapbrook, other than that it is the result of a miserable consortium of housebuilders given free rein by feeble, philistine placemen obeying irresponsible government diktat? It is dressed up as somehow beneficial and the only possible course, when in truth it runs contrary to all that needs to be done for a future in which there must be a reduced population; higher home occupancy; less travelling; minimal energy consumption; more self-sufficiency; and absolute protection of fertile farmland.

Do as the E. & T.V.R scout did in August: go to Cranbrook and then go to Poundbury, Dorchester.

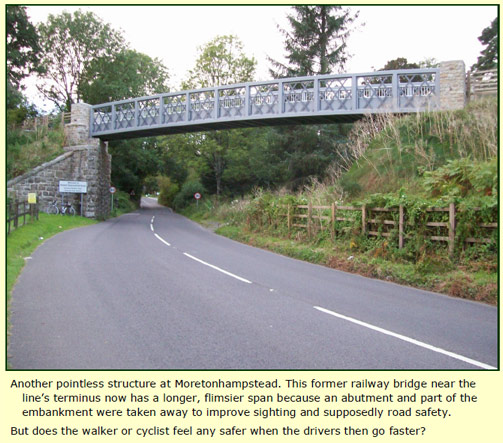

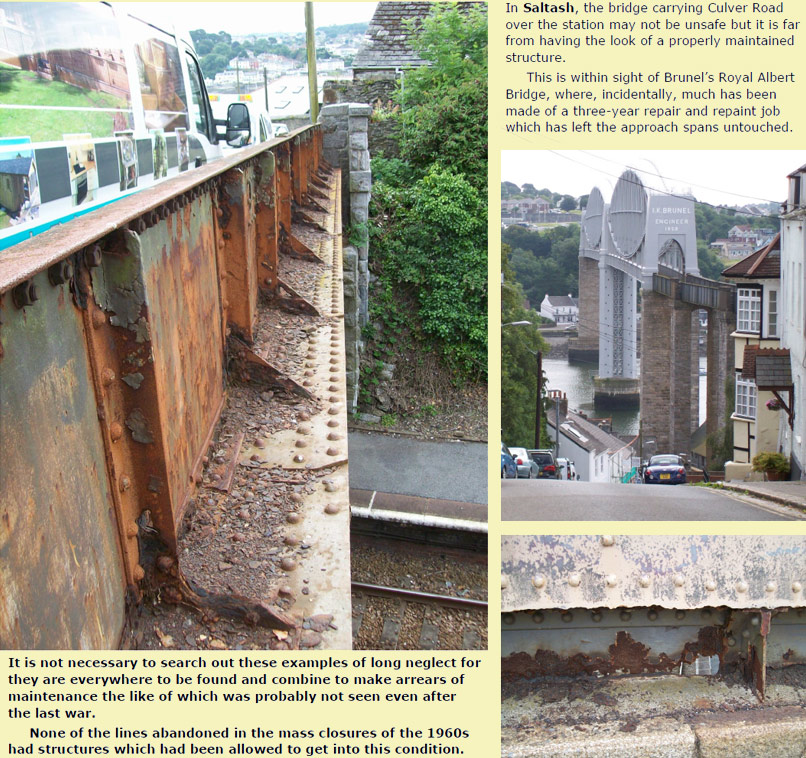

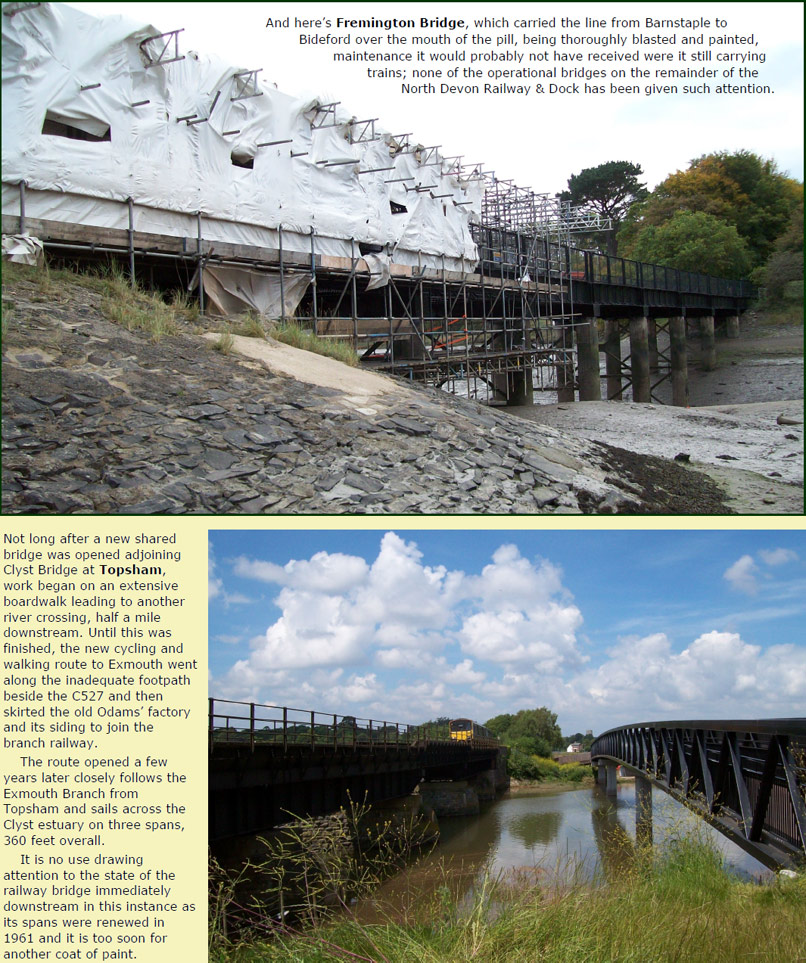

The Fancy Bridge Competition — Modern-Day Follies

All over the place, bridge engineers seem to be vying with each other to produce the most flamboyant design. The visual appeal of these mostly pedestrian crossings is perhaps meant to deflect anyone who might question their purpose.

For so many of these new bridges duplicate nearby structures or are built along new routes that themselves merely deviate unnecessarily from an existing route as an escape from motor traffic.

Shared-use paths made along the routes of defunct railways have produced most examples of this bridge explosion. Where substantial masonry or girder bridges were casually demolished, a new slender one has been erected, for it is now deemed not safe even to cross a busy road, let alone walk or ride its length.

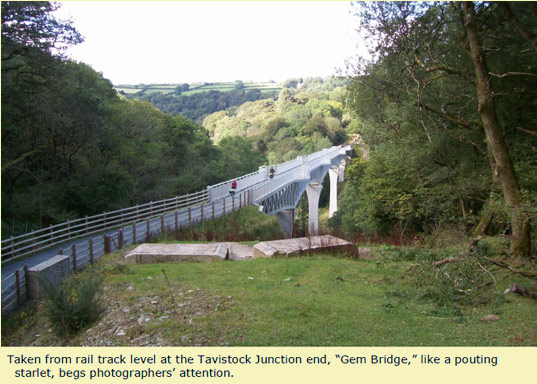

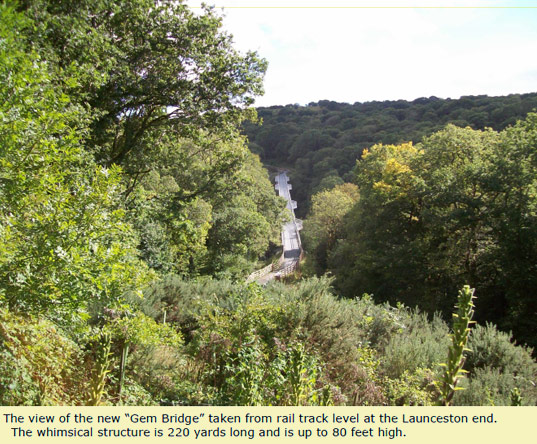

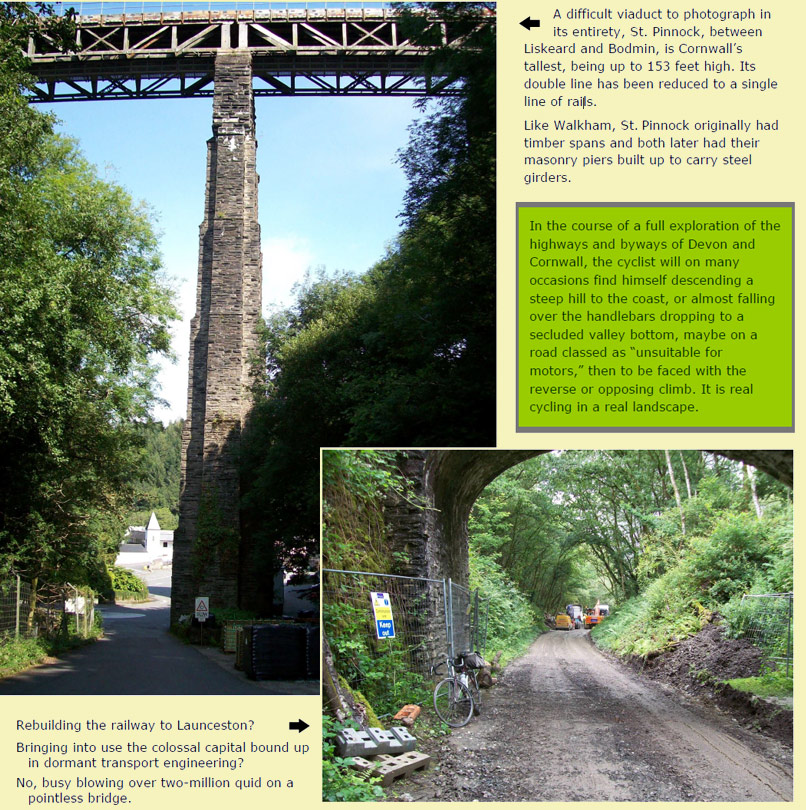

The Launceston Branch and Walkham Viaduct

The branch line from Plymouth (Tavistock Junction) to Launceston was closed to passengers in 1962 and entirely in 1966. Over 30 miles of railway, its 14 stations, its earthworks and structures, were abandoned. Call it £10-million per mile at today's costs for an idea of the capital value that was written off.

Between Horrabridge and Tavistock, the railway crossed the valley of the River Walkham on a viaduct 367 yards long and up to 130 feet high, originally with timber spans, but from 1910, steel truss girders. Just three years after the line closed to passengers, in the manner of an army covering its retreat, the impressive viaduct was demolished.

The path that had first been made along the track from Marsh Mills 20 years ago reached the site of Walkham Viaduct in 2011 and it was decided to build a new pedestrian crossing as a showpiece, not as a practical necessity. Money was available to the county council from the sale of Exeter Airport and so £2.1-million was spent building what was called "Gem Bridge." Described as "echoing the engineering brilliance of Brunel," it has already won civil engineering project of the year (under £3-million) at the British Construction Industry Awards.

Had the line remained open and been modernized and developed as part of a general purpose public transport system, much of the traffic that today makes roads unsafe and unpleasant for pedestrians and cyclists would have been won to rail; and this is without considering the efforts that might have been made to moderate motorized movement in general.

People would not then have been able to walk or cycle along the railway, but would have gained a much greater freedom: to take the train to stopping places along this picturesque line, from where to explore an extensive and unthreatening road network.

It must be taken that the engineers, Dawnus Construction, would be capable of rebuilding the railway viaduct. Surely they would have gained more professional satisfaction doing this than putting up a folly to attract judges' and photographers' attention; and, if there were any genuine desire to echo the brilliance of Victorian engineering, it would be by showing how little concrete and steel is needed today to support a heavy train.

The "Drake's Trail" (a bit of the Launceston Branch of the Great Western Railway, lest it be forgotten) is part of a bigger project, "La Velodyssée," which it is intended will stretch from Ilfracombe, across the channel to France and as far as the Spanish border. From now on, it is a safe bet that every item of publicity for this tourism initiative will include a photograph of "Gem Bridge."

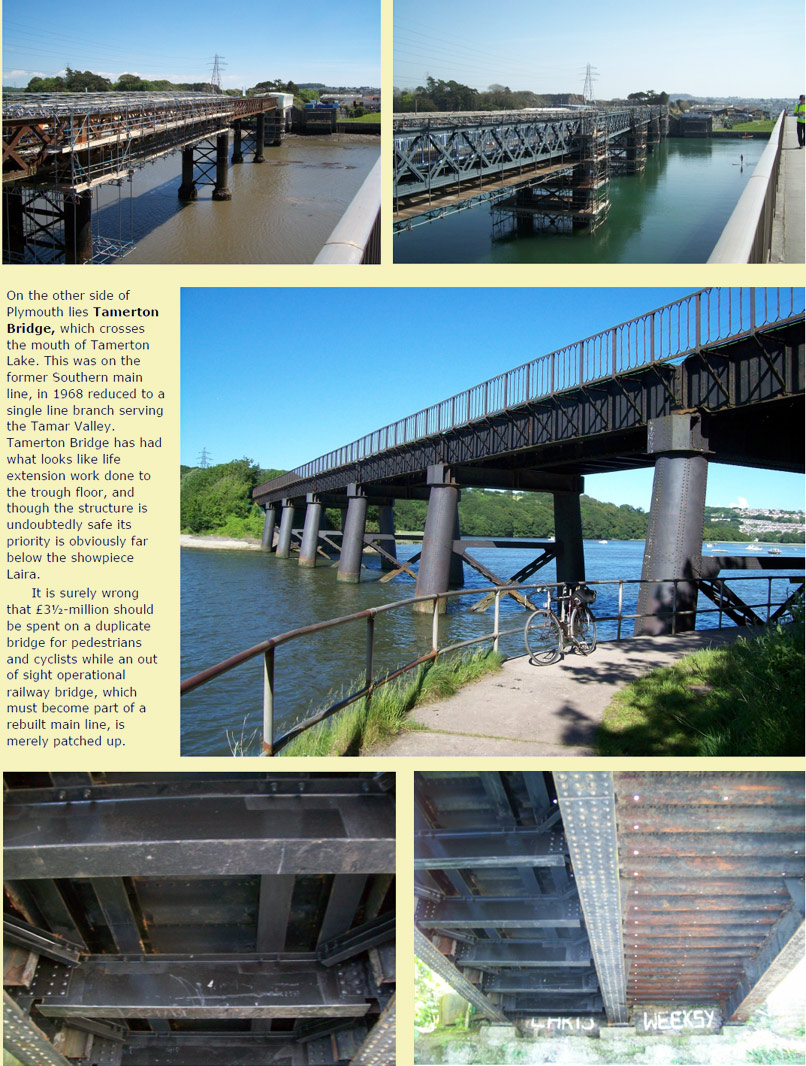

Laira Bridge crosses the River Plym just upstream of the road bridge of the same name. It carried G.W.R. trains to Yealmpton and Southern trains to Turnchapel, the junction being at Plymstock, behind the camera. Both branches were among the early closures. Cement traffic was worked out of Blue Circle at Plymstock until 1987, when the line was completely closed.

Considered an eyesore, Laira Bridge was put under wraps for a year. It emerged, repaired and repainted at a cost of £3½-million and now carries a shared path, duplicating the one yards downstream on the road bridge. Of course, it may be that this footpath is wanted for road widening but no plan has yet been revealed.

To the right of the camera is The Ride, a road alongside the river. The underline bridge here was demolished to allow the road to be widened and now another new bridge spans the gap, it being planned to continue the path towards Plymstock.

The south-eastern suburbs of Plymouth have grown enormously since the branch lines closed and the new town of Sherford is to be built here, with a population rising to 12,000.

The whole place will be within a mile of the former Elburton Cross Station, closed to passengers in 1947, so it may be imagined that the developers would be obliged to contribute towards the reinstatement of the railway as part of the sustainable transport plan.

But, no, the answer to the already chronic traffic congestion on the roads leading into Plymouth is a cycle path on an old railway.

Right: Rotting sleepers on the course of the Yealmpton Branch leading towards Billacombe and Elburton Cross lie hidden from users of the dualled A379, where motor traffic is sped on its way to the choked city.

Transport for the High Achiever

Selling Tonka Toys to Toddlers at Christmas

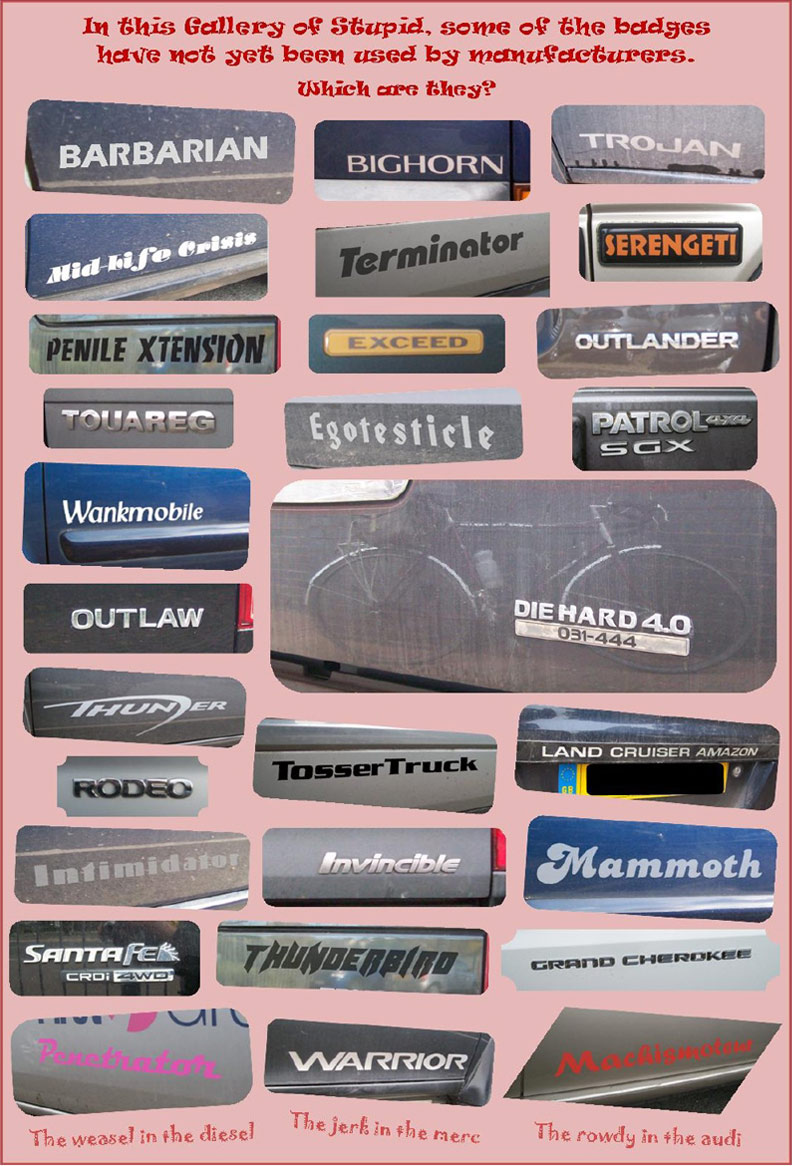

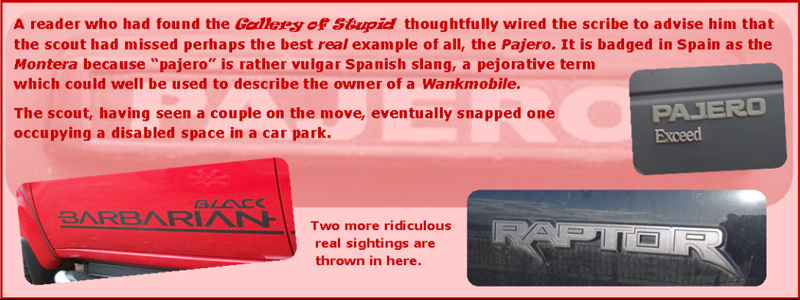

Buried away somewhere in the back rooms and eyries of the vast car plants of the Far East and elsewhere are small sections that come up with badging for the various models and the countries to which they are sent.

Or it may be that the polling and research that goes into what name will best sell a model is put out to agencies. Either way, what the manufacturers want is a name to match or create an image; a name to make a connection of some sort.

Cars have always been badged. Once, they were given evocative, classical, faintly pleasing names. Functional names were used as well, based on size or capacity. An example of stylish simplicity was the name given to the first Italian scooter: Vespa, because Rinaldo Piaggio thought it sounded like a wasp. The three wheeler which followed was dubbed Ape, or Bee.

Then, it was not so important; it was more about recognition. Now, a great deal depends on effective marketing and the more grand the model, the harder they have to work in those back offices to complete the package and avoid losing sales to rival makers.

A new class of expensive vehicle has appeared, commonly called the "four-by-four," although known also as the "off-roader," "all-terrain" or the euphemistic "Sports Utility Vehicle." Whatever the name, it is a class that has very clearly distanced itself from the move towards cars which are compact, economical and aerodynamic, by introducing heavy, boxlike designs with big engines, which put as much rubber on the road as possible. All the advances in efficiency made in the 1980s, futile though they were in the long run, were set back at a stroke by the popularity of this new breed.

So, what low mentality was meant to be attracted to these big, ugly crates which can cost over £60,000? This is where the badging gives it away, for why would those focus groups have settled on Die Hard, to take an example? The name must have been taken from the series of all-action films in which an invincible tough guy played by Bruce Willis saves the day for peace and justice every time. Those who drive the vehicle of the same name, it must have been gauged, want to be like Bruce Willis or the fictional, gun-toting, wise-cracking character the actor played.

It is scarcely believable that there are feeble-minded men who want to drive a car with that imagery in their heads on the streets of Britain, among pedestrians and cyclists and other road users who should be able to go about freely and safely without feeling they are on a Hollywood film set.

Die Hard with the four-litre engine, should anyone be interested.

To counter their many critics, shame-faced owners of these vehicles—the shameless bother to make no excuses—very often cite necessity as the driver, roads and city streets alike being so badly deteriorated these days as to resemble the tracks of the pre-turnpike era. Others quote safety; the Hummers' occupants feel safer, even if the overall effect of their presence on the road is a reduction of safety.

In some cases, the high-traction capability, notably all-wheel drive, is the real selling point, but for decades this was adequately met by the eminently practical and rugged Land-Rover and its close derivatives. To the majority, in all honesty, there is one over-riding attraction: these vehicles make their owners feel good — powerful and superior.

The ownership of any car signifies a certain lack of concern, although it must be said that not everyone enjoys driving the wretched things and many would love to be shot of them. There is no obvious way of knowing whether those who take part in the automotive madness are happy or not. After all, many environmentalists, off-gridders, organic growers and other exemplars of low-impact living own cars; but have a ready line when they voice their displeasure at the world which forces them to drive everywhere.

Whatever the views of the ordinary motorist, those who buy the gross, clumsy, mobile abominations make their position absolutely clear and dispense with the need for a sticker in the rear window which says: I DON'T GIVE A SHIT.

Leaving aside the regular crooks, spivs, pimps and jumped-up barrow boys, many purchasers of monster vehicles are apparently intelligent, high-achieving pack leaders who would in any normal order be the ones most likely to make reasoned judgements about transport.

Instead they are sucked in by the moronic advertisements in glossy magazines aimed at those in the high income brackets who may be at the top of their professions, but who the researchers have identified as being morally weak.

The vehicle in the unlikely or impossible scenario is accompanied by staccato sentences; hardly ever more than one sentence to a paragraph; often a sentence without an object or a verb; large print for little mind.

We think you'll like the new Goliath®.

It's big.

It goes, too!

Vrrrm!

And, on the gogglebox, there is very little difference in style and presentation between efforts to sell the most expensive motor car and Tonka toys to toddlers at Christmas.

Unsprung Dork Sputnik

Clarksons

Whether Jeremy Clarkson really is the man whose idiotic opinions are spouted in newspaper columns and television shows is not important, because he or his created character has packaged a common viewpoint and given it a name.

Clarkson first appeared on television's Top Gear, a programme originally fronted by Raymond Baxter and other mature types, intended as a serious digest of cars and motoring. Its reviews of new models were sober and useful. It covered functional vehicles on occasion, such as a light delivery truck, and it may even have passed comment on the Sinclair C5. It was possible to view purely out of a mechanical interest.

Probably to boost flagging viewing figures as the general intelligence level plummeted, young, brash presenters were hired and the show began to degenerate, with its cars, lent by their makers, being spun along open roads accompanied by inane commentary and popular music. All pretence of seriousness was dropped when the show set up base in a hangar, where the presenters now loll around like overgrown schoolboys and the airfield outside is used as a driver's playground.

Of course, it is only entertainment, but looking at the impressionable dimwits in the standing audience, it must be that the constant exaltation of the car, the fast and aggressive driving, the disdain for other road users and the dismissal of environmental concerns acquire legitimacy and become a sort of crappy credo, one bought by the bulk of viewers.

So it is that an unfit, unkempt oaf with a knack for the pithy line, has knowingly or not become a spiritual leader whose disciples the cyclist can readily identify.

There is no doubt that the talk in pubs and other places which tends to reinforce the teachings leads to stupidity on the road. It is hoped that a darker element is not emboldened to act violently in the name of Clarkson.

This was written before Jeremy Clarkson was sacked by the Beeb after a wrangle with a Top Gear producer.