These 31 miles of line are undoubtedly the most travelled by the scout, either on their own or as part of longer journeys.

He must have ridden behind steam engines with his parents. Diesel hydraulics hauled the trains that took him to and from his boarding school in Taunton. He has since enjoyed diesel electrics, H.S.T’s. and D.M.U’s, often choosing to stand at an open window to observe all the very familiar landmarks.

Finally, at the end of his life, he has had to witness the worst abominations ever put on rail: electric trains which have to carry around diesel engines and tanks of gas oil; and whose bodywork is already corroding and fatiguing.

Exeter (St. David’s)

The Red Cow crossing attendant, usually a green-carded man, looks out for pedestrians, who were able to cross while the road gates were closed; and can still do so today when the barriers are down.

The former Railway Clearing House building is at left. Middle Signal Box is squeezed between the Up Relief and the shed road. The attendant’s hut is by the door.

The Transfer Shed and later extension is at centre.

An engine stands in the banking spur connected to the lines used by Southern trains. Another engine moves to the rear of a train in Platform Three or on the Down Main. The siding had an unusual “scotch block,” a great lump of iron that was swung up onto the rail, in place of a trap point.

Ward & Co’s. store is seen at right, and beyond, other traders’ premises are visible on Cowley Bridge Road.

The line at right leads to Platform Two, the Exe Valley Bay, and “Hyde Park” siding.

From right to left, the lines are: Down Platform; Down Main; Down Middle; Up Middle; Up Main; Up Relief and shed road. The track layout was heavily rationalized when Multiple Aspect Signalling was installed in 1985. The Down through line was taken up and the Down Middle became the Down Main.

The Transfer Shed is the only railway building in this picture which remains.

There used to be no public right of way over the two crossings – Exwick Crossing over the goods yard and avoiding lines is off picture at left – and it was said that they were closed once a year to prove possession.

A pre-war northern bypass was taking shape which would have been carried over the railway, perhaps between Middle Box and the Transfer Shed, on a flyover. Prince of Wales Road would have been linked with Valley Road in Exwick, which it is thought was built for this purpose. Exwick Road, Buddle Lane and Cowick Lane had all been straightened and widened.

Parcels Traffic contains views of the bay platform.

“Long gone are the days when the crack Limited (“Cornish Riviera Express”) used to run non-stop to Plymouth; and a grand sight it made going at speed through St. David’s, the hardest work for its immaculate “King” lying ahead, with the unassisted ascents of Dainton and Rattery, for which it would need to pick up water from the troughs at Exminster. Latterly, one of the few occasions when the back board (distant) came off was for the train of 22 empty Polybulks all the way from Switzerland to Cornwall, which, not needing relief, would hurtle through at 55 m.p.h. Another use for the through road was for Southern Up freights to attach their banking engines. I would step out some mornings to watch a pair of howling “Thousands” (Class 52s) work the Westbury to Exeter Central cement up the bank. Crikey, it would make you weep if that sight could be recreated. But the diesels have gone; so has the cement; and the through road is just bare ballast.”

From “Twenty-One Years with British Rail,” E. & T.V.R., 1995.

The Grade II listed Transfer Shed stands forlornly at centre. Exeter was at the extent of the narrow (standard) gauge and goods consigned further west had, if carried in narrow gauge wagons, to be transhipped into broad gauge ones. The narrow and broad openings can be seen. The most recent scheme to find a new purpose for the building was scuppered by Network Rail.

The new building behind it is the Traction Maintenance Depot. It occupies the site of the Goods Shed and much of Old Yard, the original goods yard. A few truncated lines remain to the east of what was Exwick Crossing; a track maintenance machine stands in one of them; to the right of it is the remainder of the Up and Down Goods avoiding lines.

In the foreground, alongside Cowley Bridge Road, is the former New Yard, built to provide additional capacity and to allow traders’ premises to be directly served. A track maintenance depot, kept as scruffily as the rest of the railway estate, occupies some of the yard today.

Since the demise of British Rail’s Speedlink service more than 30 years ago, not a ton of revenue-earning freight traffic has been handled here. The track authority and the train operators do not use rail transport for their stores and consumables.

Once, four signal boxes would have been seen from here. Two would have been in picture: Exeter Middle and Exeter Goods Yard; Exeter East and Exeter Riverside Yard lay off picture to the right. +

As a wartime measure, Riverside Yard was built on waste ground between the main line and the river, the goods lines were extended to Cowley Bridge. Italian prisoners of war helped to lay the seven through sidings of the new marshalling yard. The signal box, opened in 1943, stood roughly at centre.

In 1965, upon the closure of Hackney (Newton Abbot) as a marshalling yard, six single-ended sidings were added in what was known as “the field”; prior to this, a siding had been slewed as required to allow tipping of spoil.

East Box, now off picture at left, was closed in 1973 and the connections to the avoiding lines and New Yard were taken out.

Two more sidings were added to Riverside in the late 1970s, bringing the total to 15.

Riverside ceased to be a marshalling yard after the demise of Speedlink. Since denationalization, the track has been heavily rationalized and now principally serves as an aggregate depot. Thousands of tons of stone are brought each week from the Mendip quarries, which is then hauled over a busy level crossing and along residential roads.

Two trains of VTG, 77-tonne capacity hoppers, new from the Polish manufacturer in 2024, are standing in what could be roads 12 & 13. Redundant power station coal hoppers stand at right in No. 3 or 4 of the original yard. +

Cowley Bridge Junction

The junction of two turnpikes and the confluence of two rivers was not the best place to introduce the junction of two double lines of railway.

Before the railway was built, the Barnstaple turnpike made a junction with the Tiverton road in front of the Cowley Bridge Inn (now closed) at right.

In June, the scout began following the North Devon line from the bridge at Cowley, but for this piece he took the Exe Valley turnpike which goes to the right of the old inn.

Cowley Bridge Junction Box is at left.

The river bridges can be seen as they were before the diversion work in the 1960s, when the North Devon line was singled.

Flooding at Cowley Bridge Junction.

Since the above piece was written, the Environment Agency has raised the city’s flood defences and these now extend upstream to Cowley Bridge. A channel has also been made beneath the G.W. main line just east of the junction.

Cowley Bridge Junction Floods is a film which explains in great detail what was done here by railway engineers in the mid-1960s.

The scout’s coverage of the Exe Valley Branch opens with shots taken from the carriage between Cowley and Stafford Bridge, and at North Bridge.

Stafford’s Bridge

The O.S. marks it as Stafford Bridge.

Grade II* listed Pynes, the former home of the Earl of Iddesleigh, nestles on the valley side at right.

Exeter’s water treatment works of the same name can just be seen below the second pylon.

The transmitter at Whitestone pokes above the hill behind the third pylon. +

On the bridge the scout met the farmer at Woodrow doing his rounds. He asked the scout if anything special was due, as that is the only time the farmer sees anyone lingering on the bridge.

They talked about grassland, milk production, flooding, Network Rail and farming in general. He told the scout that his pasture had been flooded twice this year and that he had to walk over it each time to pick up debris washed down river. He told the scout that a lot of damage can be done to a forage harvester by a metal can.

He had complained to Network Rail about the state of the occupation crossing. He told the scout that he once phoned to ask for three minutes to get his herd across, only for a cow to get a hoof caught in the timbers (at long last replaced by rubber units). Trying to extract it, he could hear the phones ringing – the signalman asking for “line clear.” +

In making his way around to North Bridge, the scout stopped on the bridleway leading from Woodrow Barton to Burridge Road and looked across the valley.

North Bridge

Stoke Canon Junction

Additionally, the branch, seen diverging left, was given its own platform, shorter than the Up line face of the island.

The station was closed in 1960 and the Exe Valley service had only months to run before it was withdrawn in October, 1963.

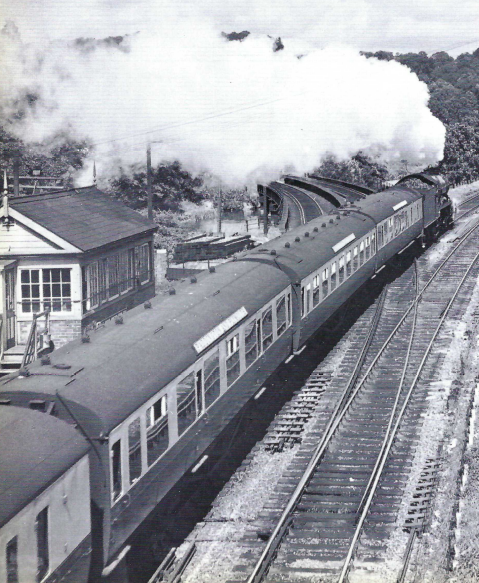

The Tiverton train has only slowed to collect the token from the junction box, off picture at left.

In a few years the goods yard at top right will also be gone. Photographer: Peter Gray.

Behind are the sheds on the site of Stoke Canon Paper Mill, once served by a leat fed from the River Culm. +

Stoke Canon Crossing

The scout stopped here in 2020 on a ride to Silverton.

This is looking from the river bank near the former Fortescue Crossing, on the Exe Valley line. +

Sandy Lane Crossing

This foot crossing was closed for several years and was not immediately reopened, even when work had been done to improve it, including the installation of warning lights.

Rewe Bridge

The “vee” of the turnpike and railway beside the camera in the first picture above was once the base of Munro Plant. The scout was at prep with Clive Munro, the owner’s son.

Columbjohn Bridge

The road here shortly passes over the older Paddleford Bridge across the Culm, whose valley the railway follows.

Many years ago, when the scout came off late turn at St. David’s, he would ride the Exe Valley in the dark, sometimes as far as Tiverton, just for fun. He remembers being on this bridge on a still evening and hearing the milk accelerating away from Cowley behind a Thousand. The closely, almost uniformly, spaced axles of Miltas (telegraphic code for milk tanks) gave the trains an unmistakable sound. Even on continuously welded rail, a slightly inaccurate weld would have the same effect as a joint. Seeing the 1640 St. Erth or the 1730 Lostwithiel (there were two trains some evenings) pass here at 60 m.p.h., with West Country milk for London breakfast tables, gave a young lad the feeling that he belonged to an industry that was doing something useful. It was one of his jobs to advise the Milk Controller at Paddington of the formation leaving Exeter, where portions from Chard, Torrington, Lapford and Hemyock may have been attached to tanks already picked up at Totnes.

Paddleford Bridge has a distorted arch, but this should not worry passengers as a three-tonne restriction has been imposed.

In the railway’s campaign against the demolition of a bridge on the Teign Valley route, the scribe drew attention to Paddleford as an example of real risk. This letter has a view of the distorted arch.

Silverton

The station, the private siding and the paper mill were covered in 2022.

Hele & Bradninch

The scout continued from Clysthayes and turned onto Strathculm Road, which enters Hele very near what must once have been the main entrance to the paper mill.

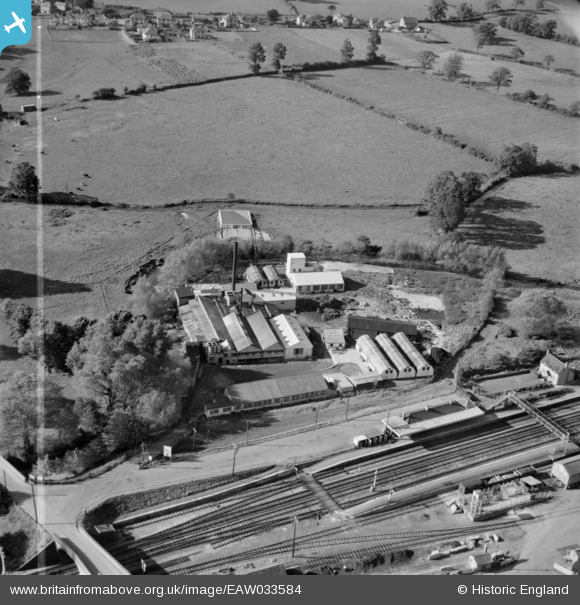

Logging in and enlarging this photograph reveals an L.M.S. mineral standing near the gate, next to a horse and cart. A S.R. mineral stands on the nearest bridge. What looks like a small internal wagon stands on the line leading to the upstream bridge, while a van and two Conflats with “B” containers stand in front of the shed at right. A raft of wagons stands partly under the covered loading bay. A lone van stands at the nearest end of the floodplain bridge, not then paved for road vehicles.

The station goods yard at bottom right is full of trucks. “Wm. Ackland & Co. Ltd.” is marked on the roof of a trader’s building.

The ends of the platforms can be seen, with neat shrubs by the fences.

A pony and trap approach the crossing on Station Road at far right.

Hele Railway Flooding (7th July, 2012)

A little way beyond the M5 bridge over Station Road, on the right, bordering the old A38 and rather hidden from view, is railway activity of a kind. Leaky Finders Ltd. is a heritage steam specialist company. The scout joined a Devonshire Association visit to the workshops in November, 2023, and enjoyed looking at the innards of antiquated engines.

The scout left the turnpike and followed Waters Lane as far as the railway bridge.

Nag’s Head Bridge

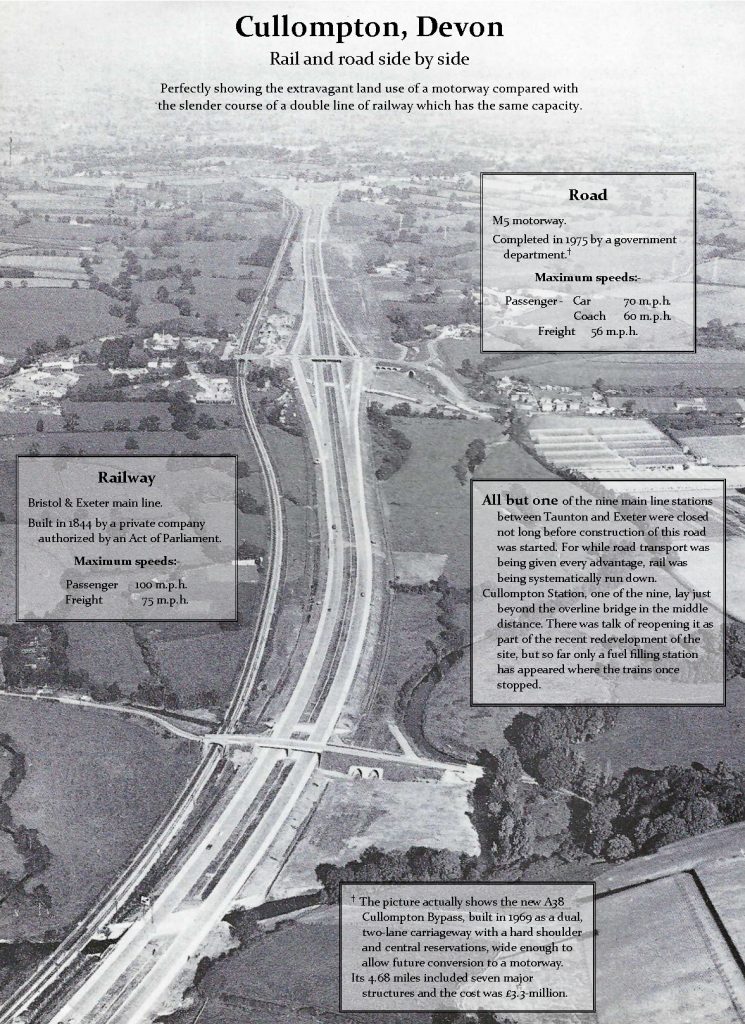

The turnpike bridges the railway here, on the approach to Cullompton. It crosses back at Willand. Another crossing is made above Whiteball Tunnel and then at Beam Bridge. The motorway stays to the east of the railway between Exeter and Taunton.

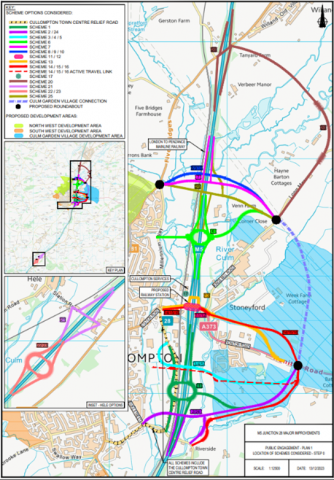

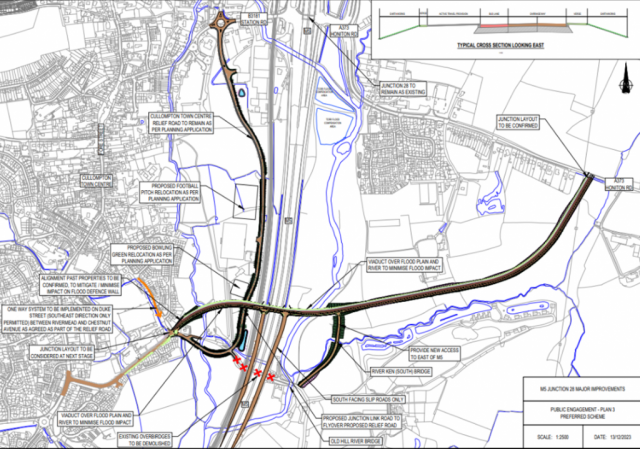

March, 2025: Two days before the scout stood on Plymtree Bridge (above), it had been announced that construction of the Cullompton Town Centre Relief Road was to go ahead. This is just a small part of the 25 options considered in recent years. A new road will link the Station Road roundabout with Duke Street, leading to Plymtree Bridge and make a route to the old main road via Meadow Lane.

Meanwhile, Cullompton Station is nowhere near being reopened, despite this first being proposed in 1995.

It and the railway are seen from Willand in the distance to their crossing of the Culm at the bottom. Plymtree Bridge is seen a little to the north. What became Junction 28 can be seen, with the site of Cullompton Station to the left.

Before 1969, all the traffic went through the town. Then it was relieved by the bypass. Then the bypass became part of the motorway. Now a relief road is needed between the motorway and the town. And a start hasn’t yet been made on the 5,000 homes of the “sustainable” Culm Garden Village. +

“Unfortunately due to constant rising utilities, employment costs, food costs and very healthy competition in the town, it’s no longer financially viable for us to carry on. We are a tied house so we are unable to compete with the prices the freehouses in the town can offer.”

The yellow vehicle is about to cross Long Bridge over the Spratford Stream and the red car is on the railway bridge; the former station entrance is just behind it.

Cullompton Station

The road bridge has since been widened on the station side using concrete beams.

Some of the buildings of The Culm Leather Dressing Co. Ltd. Works remain and the site is now a trading estate.

Before the remodelling, there had been a siding behind the station approach.

The town extends north along the turnpike at the top of the picture. Housing estates have now smothered all the land between the Culm and the turnpike, and rapacious development is continuing.

In the mid 1990s, when there was talk of reopening the station, the scout approached the owner of the goods yard, Boulevard Land. The Goods Shed and feed store, the end of which can be seen at bottom right, remained and the scout wanted to recover materials from the latter, as the building was similar to the one that had been removed from Ivybridge to Christow. The scout’s contact was quite pleasant and helpful but the idea was not pursued; the timber frame was riddled with worm and the cladding was six-inch corrugated steel.

All the fanciful talk of the 1990s amounted to nothing and the goods yard became a tawdry motorway services station.

With Wellington and Cullompton becoming housing growth towns in the new century, and by far the largest settlements between Taunton and Exeter, proposals to reopen their stations now had greater justification. It seemed that the government award of £5-million in 2021 to work up plans for Wellington and Cullompton almost guaranteed that they would be built, but in 2024 the new Labour administration, discovering that the country was broke, announced a review of all railway schemes.

The far newer £34-million road scheme, a relief road linking Station Road with Meadow Lane (effectively, with Millennium Way, completing a second Cullompton bypass), was given the go ahead in March, 2025.

Beyond Cullompton, the line leaves the Culm Valley and climbs to Willand.

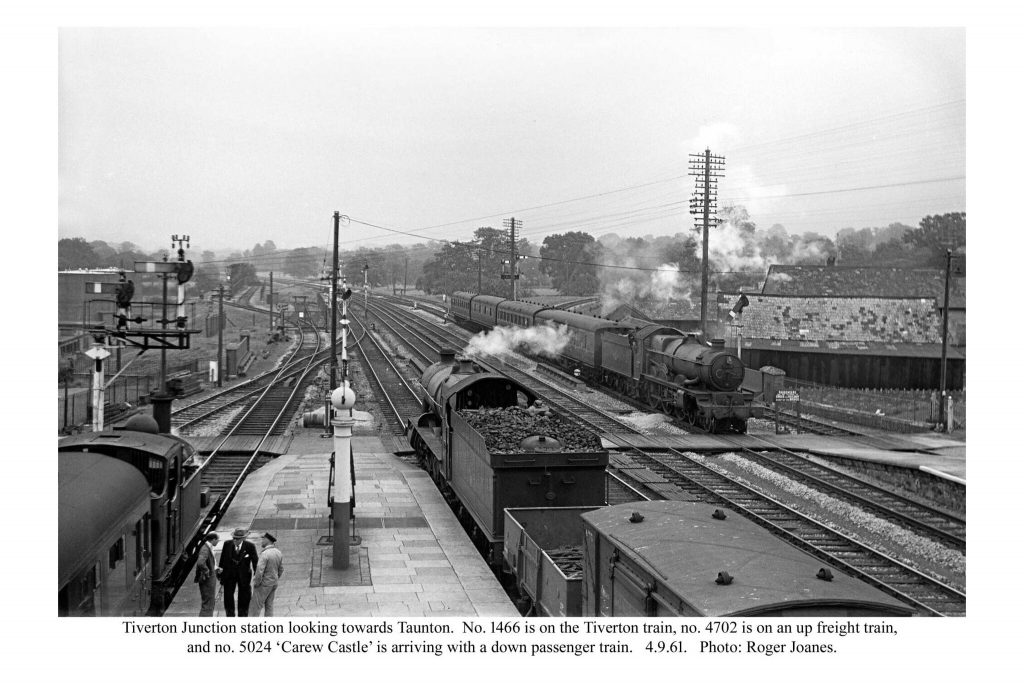

Tiverton Junction

Mail apparatus once stood beside the Down line and possibly the Up. Postmen would have reached it from this bridge.

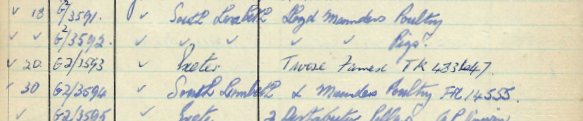

The next bridge gave access to the Lloyd Maunder factory in the vee of the junction between the main line and the Tiverton Branch. This was established in 1914 and continued as Lloyd Maunder until sold to 2 Sisters Food Group in 2008. +

Dean Hill Road from the bridge once led towards the end of Station Road. It was severed by the motorway and the new Lloyd Maunder Road was made to the gate of the factory and continued to the former passenger and goods entrance on Station Road.

The scout had passed the factory gate three times before in 2024 and had eyed the private railway bridge from which he was sure the best view of the former station could be obtained, but he had shrunk from stopping at the gatekeeper’s office.

On the fourth ride past, still certain that he knew what the answer would be, the scout thought he would ask anyway whether it would be possible to take a photograph from the bridge.

A burly security officer came to the window and said politely that it could not be permitted. Seeing the scout downcast, however, the fellow then advised that if the enthusiast were to send a wire, it might be possible for him to be escorted onto the bridge.

Even though he would not have had much intention of acting on it, the scout enquired whom he should contact. Security was about to jot down the address when he spotted someone in authority by the gate. “Just a minute,” he said, as he left from the back of the office and waited his turn to confer with the man.

The scout felt himself being observed before the man came towards him with outstretched hand and introduced himself as Geoff. The scout had not appreciated the concern that he may have been a protester or an “animal rights” activist.

On the bridge, before he returned to his office, what the scout later learnt was the General Manager, Geoff Pugsley, told the scout that he remembered catching trains from the former station.

After thanking him for his kindness, the scout walked back to the gate with security who told the scout that the factory and the houses opposite were still owned by Lloyd Maunder – the brothers had called in recently – and that a million hens a week were slaughtered.

Having just read Simon Fairlie’s recollections of life in the 1950s, the scout was able to say that chicken, being expensive. was once only enjoyed at Christmas and Easter and that beef was the staple.

The station which might have been Willand was instead named “Tiverton Road,” until the branch opened in 1848, when it became Tiverton Junction.

The lavish station of 1932 was stripped of its branch lines, its engine shed, its goods yard and its private sidings, before being closed and replaced by a reopened Sampford Peverell in 1986. The platform lines and one siding remain.

Shamefully, unlike Geoff, the scout never used the station, although he did visit it when it was open. However, he was on an Up D.M.U. in recent years which was looped here to let a fast train overtake. +

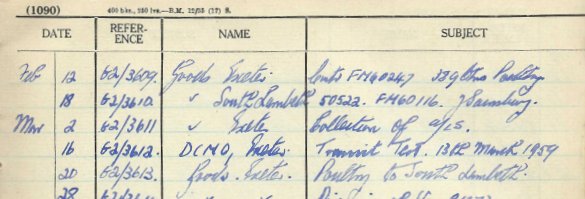

“AF” and “FM” insulated containers, used by Lloyd Maunder, are often mentioned in the G.W.R. Letter Register which came from Tiverton Junction and was later kept as a Visitors’ Book in the railway’s Camping Van at Christow.

The line which led to the Culm Valley platform remains as a siding. Beyond the island platform is the quadrupled main line; the platform lines remain as loops. On the far side of the other island was the Tiverton platform. The goods yard was to the left and behind the camera.

Quadrupling of the 1¾ miles between Sampford Peverell and Tiverton Junction was proposed as part of the 1930s improvements.

Copyright: Roger Joanes. Shared under Creative Commons. +

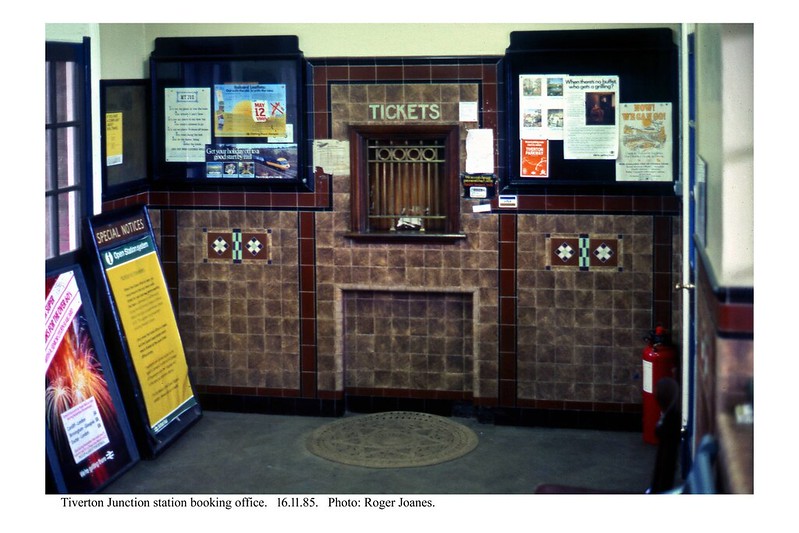

Copyright: Roger Joanes. Shared under Creative Commons.

Copyright: Roger Joanes. Shared under Creative Commons. +

Tiverton Junction loco shed is seen at left.

Copyright David Glasspool Collection.

At right can be seen the Railway Hotel, later demolished to make way for the motorway.

Willand’s god-awful housing estates, centred on the old A38, give the impression of a new settlement but the heart of the old village can be found, about a mile from the former station.

Muxbeare Lane, off the old A38 north of Willand, goes towards the motorway. At great expense, a path has been made from here to Tiverton Parkway.

Ahead can be seen the rise which legend has it was made to accommodate the bridge over the Culm Valley Branch, but which was actually necessary to achieve adequate clearance over Station Road. +

The path sees very little traffic but has of course attracted dog walkers. +

Tiverton Parkway (Sampford Peverell)

Before the railway was built, the road continued in a straight line. Then the road was taken left and up to the bridge over the railway and the old road became the station approach. Now the bridge over the line carries the North Devon Link Road.

Two car parks lie behind the camera to the left; the station long ago outgrew the original car park. On a weekday in September, 2024, the scout counted around 70 empty spaces in the outer car park

Eggesford to Sampford Peverell.

A permissive path follows the Spratford Stream beneath the dual carriageway and across the fields. The artists’ “gallery” beneath the A361 must only be seen by a few.

The line can be followed using quiet lanes or the Grand Western Canal, which is less than three quarters of a mile from the station.

Pugham Crossing

The scout photographed Pugham Crossing in 2018. He has only a vague memory of seeing the gates and hut while on his way to and from school in the early 1970s.

The lane to Pugham should only be used for access to farmland but it is probably also used by P.W. and S. & T. men for track access.

The scout hopes that the well worn turning area does not mean that Pugham has become another viewing point for wretched trainspotters; the ones who follow the unordinary workings of a supposedly sustainable transport system but who think nothing of driving their cars many miles from their homes to remote locations just to photograph a movement that breaks the monotony of a near monofunction railway, but which once would not have turned a head.

The combination of cheap motor transport, running information gleaned from the internet – better than was once available to staff – and Mughook sees grey old men, with nothing much else to do, chase to their favourite spots every time an unusual headcode pops up on Realtime Trains.

By the end of the day, the outlets for this valueless effort are awash with a thousand pictures, taken from hundreds of angles at bridges and gates, of a test train or tamper or whatever it was that caused excitement.

And the next day, they’ll turn out again to catch the light engine or steam special or Sandite going the other way. None of it will survive to be published or printed or included with an account; the bulk of it will remain buried away like a squirrel’s nuts, never to see the light of day again.