On 2nd February, 1998, a brake van and five trolleys were removed from Exmouth Junction in Exeter.

Exmouth Junction lies on the former London & South Western main line from Waterloo to the West of England, just over a mile before Exeter Central Station is reached. The Exmouth Branch makes a trailing junction on the Down side of the main line. On the Up side, there was once a large railway complex, comprising a locomotive depot, a carriage and wagon repair shop, a pre-cast concrete works and a freight marshalling yard.

Unlike the other East Devon branches, Exeter to Exmouth was spared the “Beeching Axe.” The main line has survived as a shadow of its former self, reduced to a single track for much of the way beyond Salisbury and now going no further than Exeter.

Exmouth Junction loco depot continued to service diesels after the demise of steam but closed in 1967; there is now a supermarket on the site. The concrete works closed in 1963 and the site became a coal concentration depot in 1967, replacing the rail service to many small stations; this closed in 1993. The C. & W. shop closed and part of the shed was rebuilt at great cost as a servicing facility for engineering plant but this use had ceased by 2000.

In 1995, part of the former yard remained, overgrown, in use for stabling engineering trains, and it was here that TOAD 35410 and the Plasser ballast cleaner it accompanied as a mess van came to rest, having been declared redundant.

In December of the same year, the railway made an offer of £1,000 to Western Track Renewals for the purchase of the van. No swift decision could be made, it was claimed, because the firm was in the process of being vested with its assets as part of denationalization and the ownership of the van was in doubt. Repeated enquiries were made over many months, to no avail, until the railway withdrew its interest.

Then, unexpectedly, in September, 1997, a bill for £1,000 was received, unaccompanied by any advice or explanation. The railway sat on it and then responded in October with a revised offer of £400, stating that demand for G.W. vans had waned and that the Exmouth Junction one had been vandalized; the van had been daubed in the now customary urban fashion.

Nothing came of this move and eventually a call was received requesting another letter; the previous one had been lost and the accounts office needed written confirmation in order to cancel the billing.

Taking this as an indication that the attempt to obtain the van less dearly had failed, the railway enquired of individuals at three West Country private railways as to the current worth of G.W. brake vans. Reassured by the advice received, the railway forwarded in December—nearly two years after the original offer had been made—not another letter, but a cheque for £1,000. It transpired subsequently that a higher offer had been received from Cogar Rail and that this could not be accepted until the bill already issued had been cancelled.

It was unlikely that any removal arrangements could be made before the Christmas, but word was passed to the road hauliers and the crane hire firm so that they would know what to provide for in the new year.

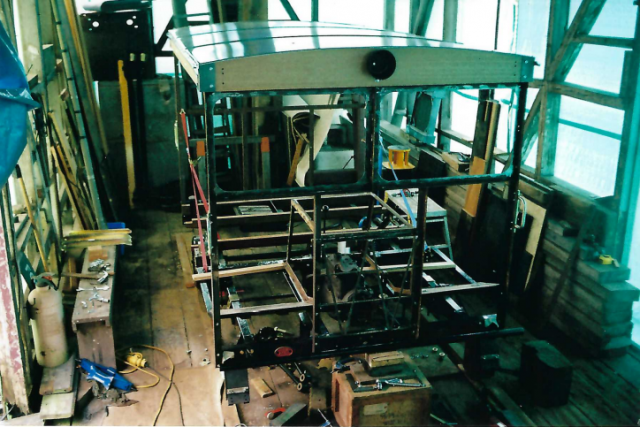

On 5th December, while the railway was working at Exmouth Junction, Andy Dyer, one of the friendly managers, asked whether the railway would also like the Matisa Track Recording Trolley, commonly referred to as Neptune, which had been stabled there for years, ever since a project to convert it into an inspection trolley had been scrapped. The railway’s answer was that the trolley’s purchase could only be entertained if it could be moved along with the brake van, a prospect which looked unlikely, given the protracted dealings with Western Track Renewals.

The fifth was a Friday and it was late afternoon to boot when a fellow on the line from an office in Abingdon said that he would make some enquiries and telephone Christow within a week. Surprisingly, but good to his word, this is exactly what he did, and when his message was answered on the Monday, he said that the Neptune trolley and the Wickham trolley (for which the railway had previously made an offer of £25, never acknowledged) could be taken away on condition that four Permaquip canopy trolleys were delivered to the Paignton & Dartmouth Railway. These terms were promptly accepted.

The work to prepare the vehicles for removal began in each case as soon as the deal was struck. Firstly, all the loose furnishings and equipment was taken away; it is surprising what will go missing when people know that something is about to leave, even when it has been available for a long time. Thus the cab of the Neptune trolley was cleared of everything, including the operators’ seats and some of the electronic units whose rubber mountings had failed. Also, everything except the built in sink unit was stripped from the brake van.

Next came the task of reducing the weight of the brake van as far as possible. It had been established earlier that the van had been weighted with concrete between the frame members, rather than the loose scrap metal used in earlier lots (perhaps because steel was in short supply in 1949), so attention turned to the steel chests built in at each end of the van which had formerly supported the cast iron sand boxes. The lamp brackets had been removed from the interior chest and a stick poked through the bolt holes into the central, sealed portion proved there was something on the bottom.

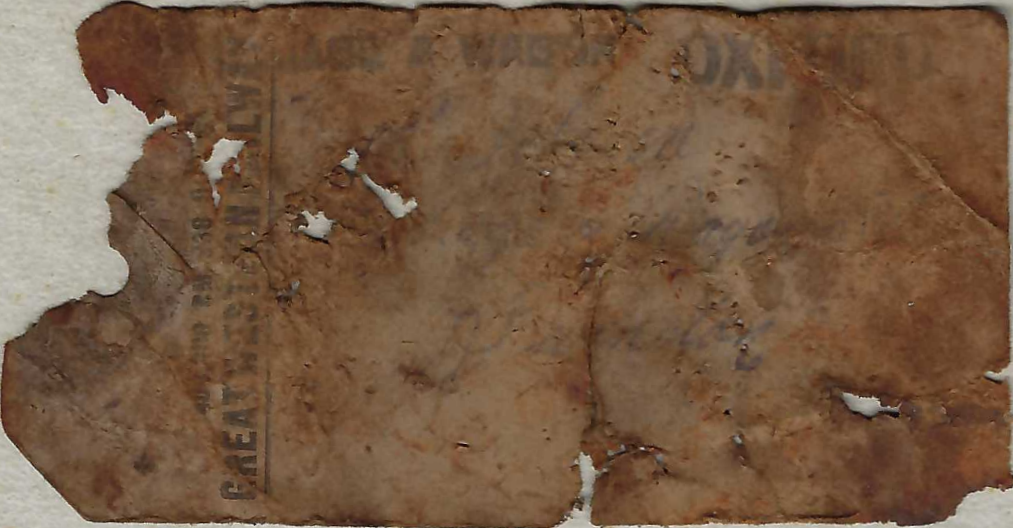

Since the chests would be coming out in the course of refurbishment, the centre compartments were opened with a cutting torch to reveal a mass of rusted, compacted scrap: rivets, bits of punched plate, old link couplings, buffer stems and general debris from the workshop floor.

There was a buffer guide which had fractured and still had the G.W.R. label attached, consigning it from Oxford to Swindon. This medley proved very difficult to separate; individual pieces had to be wrestled with and almost the whole lot had to be got out by hand. At one end, a self-contained buffer stem, sitting on its face, may as well have been embedded in cement, surrounded as it was by a rusted mass of small material.

It must have been thrown on the scrap pile from which the ballast weight sealed within the chests at each end of the brake van at Christow was taken in 1949.

Nearly 50 years later, the chests were broken open and in one of them the buffer stock was found among the encrusted contents, still with its label attached. +

After the recovered materials and equipment, including about two tons of scrap metal, were carted away to Christow, the handbrakes on the two vehicles were tested. The wells of the split axleboxes of the brake van were taken to be cleaned out, rainwater having displaced the oil and ruined the pads. The rusted journals were polished, new pads fitted and wells replenished with oil.

On 6th January, 1998, the first effective working day of the new year, a call was made to Westcountry Crane Hire to explain the extent of the job to them. And Barry Cogar, chief of the Paignton & Dartmouth, was telephoned to ask if he required all of his trolleys, one of which was at Tavistock Junction, as they were; if he had only required some for parts, it would have been cheaper to break them before removal. Helpful as ever, he wanted them all intact.

Westcountry Crane Hire was telephoned again on the 13th to discuss the requirements further and also Tim Cox Services were called to obtain a provisional date, a Monday being most favoured. On the 16th, a supervisor from the crane hire firm called at Christow to inspect the site. He had been a crane driver on an earlier job for the railway and remembered it well. On the 17th, Roy Butt Transport, which was to carry the Neptune trolley to Christow and three of the canopy trolleys to Churston, pencilled in Monday, 2nd February, for the job. By Tuesday the 20th, the other two contractors were booked as well.

There still remained some preparations to complete. The loose equipment and parts on and around the canopy trolleys were collected and taken to Churston, where the access was checked and it was confirmed that adequate cranage was available so that Roy Butt’s lorry would not be delayed.

TOAD and Neptune were moved to a suitable position for lifting and Neptune’s bogies were fetched out of a shed with a fork lift truck and placed nearby. The Wickham trolley was cleaned up and moved to an accessible place, and its trailer was taken away to Christow, along with other parts from Neptune. Short bridge rails were taken to Tim Cox Services’ yard at Drewsteignton.

At 0730 on the day, a lorry loaded with long bridge rails and a lorry and trailer with sleepers and the railway foreman left Christow for Exmouth Junction, where three men waited around in the cold for a crane and low-loader to arrive. Eventually, a phone call found them waiting at St. David’s; both firms had worked for the railway at Exmouth Junction before so there should have been no misunderstanding.

Work started at 0845 and went on without a break until completion at Christow around 1800. The three canopy trolleys were loaded first, and the lorry and trailer dispatched to Churston. Then the brake van and Wickham trolley were loaded to Tim Cox’s lorry. Finally, Neptune and its bogies were loaded to the second of Roy Butt Transport’s lorries.

A convoy then set off for Christow: two lorries, a 50-ton crane and a support truck carrying the railway foreman and the spreader beams.

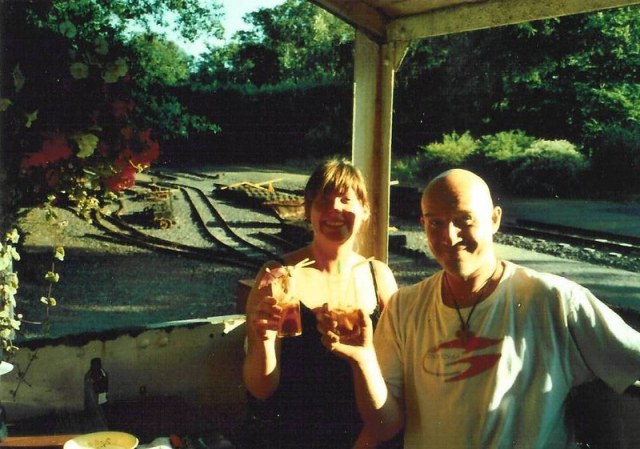

Amyas Crump did well to capture this scene, for he had been in his car behind the convoy passing Belmont Road, only a mile or so before the bridge.

Tim Cox’s lorry had to travel via Sowton Cott Bridge and so was the last to arrive at Christow, and there the fun started.

The low-loader had been employed previously to deliver the railway’s shunting loco, a shorter but heavier load than the brake van. The vehicle had been tested beforehand, negotiating the bend on the approach to Station Bridge at Christow and it had performed perfectly under load. So it was assumed that the lighter load on this occasion would present no difficulty. The trailer had a rear lift axle, which was used when empty to reduce tyre wear. Lifting the rear axle also shortened the overall wheelbase and the articulated unit could therefore be made a little more manoeuvrable in a tight spot.

For a long vehicle to make the turn at Christow, correct positioning is essential; the trailer, not just the tractor, must be close to the outside fence on the approach to the bend. However, this time it did not go smoothly; it was later discovered that the difficulty had been aggravated by the lift axle being out of order.

Watching from the site, the railway foreman held his breath as the cab of the lorry emerged from behind the trees and moved onto the bridge, only to come to stand half way across. After it had been seen to shunt back and forth several times, the foreman hot-footed it back to the bridge and found Roy Butt directing the low-loader driver as he got closer and closer to the fence at the top of the embankment in an effort to gain every last inch of the road width.

The foreman had missed the sight of the load shifting sideways on the trailer as it neared the edge of the bank on the opposite side. There was speculation as to what the owner of Station House would have done with it had the whole lot toppled over. Having a 50-ton crane on hand would have been useless because there was nowhere it could have been set up.

The tension was heightened during the shunting by the driver having to stop and speed the engine of his lorry to build up air pressure and by the drivers held up on either side wandering along to investigate, including of course the driver of the service bus.

After what seemed like ages, the tractor moved onto the bridge with the trailer following, but moving quickly towards the corner of the parapet wall on the inside which governs the width of the road. With scarcely an inch to spare, the wheels of the trailer passed the brickwork and the load was on its way along the final few furlongs.

Neptune’s bogies were swiftly offloaded using a fork lift and then, as soon as the crane was set up, the trolley itself was rerailed. When the first lorry had cleared, Tim Cox’s driver then redeemed himself by bringing his lorry through the narrow entrance to the site, thus obviating the extra crane work that would have been needed had offloading been effected from the road above.

After the brake van was rerailed, the crane’s telescopic jib was extended—a radius of about 80 feet—to put the three-quarter ton Wickham trolley onto the Cattle Pen Siding. All this took place very close to the high voltage overhead line.

There was a mishap involving the brake van but this was no fault of the contractors.

Because it had to go behind the raft already on the line, the shunting loco was started up and, when Neptune was rerailed, it was propelled to the end of the line. When the brake van was rerailed, it was allowed to gravitate a little way before the handbrake was applied. The railway foreman did not apply the brake firmly because the next move was to set back the train onto the van and clear the unloading area. It was only when directing the crane driver depositing the Wickham that the foreman glanced across to see the brake van was not behind the train, but against the buffer stop.

According to the men, when the train buffered up, the van went away down the gradient and hit the blocks with a tremendous force, jumping up as it did so. The road was later found to be six inches longer as a result and several days were spent knocking out the keys, closing up the joints and finally pulling back the buffer stop with a chain attached to the brake van.

It was later found that the van had been fitted with new brake blocks which, as they were only ever applied when stationary, had never worn to fit the wheels.

The day concluded after the crane set up again in the rapidly fading light and rearranged three containers within the building department yard.

Bless him, Andy Dyer arranged the movement of the fourth canopy trolley from Tavistock Junction to Churston.

The principal costs—Western Track Renewals, Tim Cox Services, Westcountry Crane Hire and Roy Butt Transport—totalled £2,613.28. These were attributed: £1,823 to the brake van, £656 to the Neptune trolley and £75 to the Wickham.

In 2019, it having become clear that there would never be any further interest in the Track Recording Trolley in a complete working form, the mechanism was permanently disabled and the NEPTUNE computer system removed. The National Railway Museum had given away its own example.

The section on the main web pages is kept as a record.