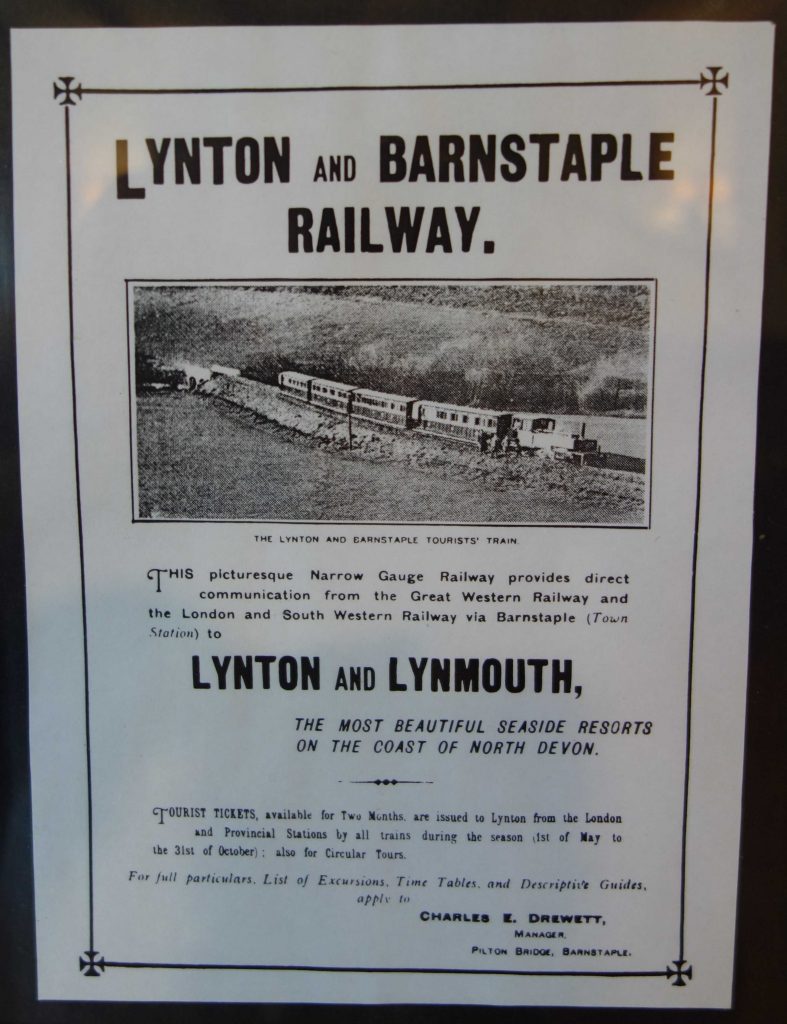

While busy at Town Station during his Ilfracombe ride in 2023, the scout had determined that it was time for a refresher of Devon’s most famous, and possibly most mourned, branch line.

He was reminded of this in August, 2024, when he joined a pal to attend the town’s Rail Fest, commemorating the not particularly significant 170 years since the North Devon was opened at Barnstaple.

The two excited boys got their “heritage trail” card stamped at the six required stops and added the former Town Station so that they could visit the hidden relic of the little railway that once went to Lynton.

“The first realization that there had been a narrow gauge “main line” railway in Devon I can still remember: it was in William Henry Smith’s in Tiverton around 1969. Finding the David & Charles book on the subject, I turned excitedly to my Father to ask what he knew of the line. His answer was casual, as mine would be today if similarly I were asked about something long gone and I had seen so much else go too.”

The Lynton & Barnstaple Railway’s Bid to Continue Construction.

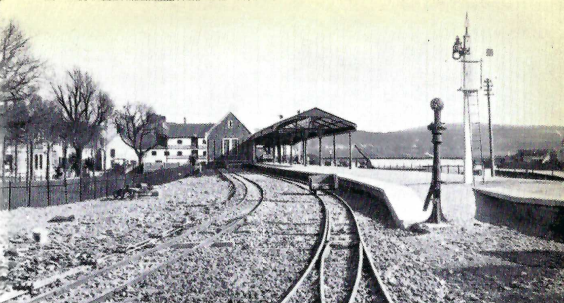

Barnstaple Town

The scout could not help but wonder, as he watched the incessant darting, fleeting movement of steel crates, much of it frivolous or unnecessary, how many million times this one scene at a road junction in a country town would have to be multiplied to give the worldwide total. And he wondered how it was all going to be electrified.

Pilton Road Crossing

Pilton Yard

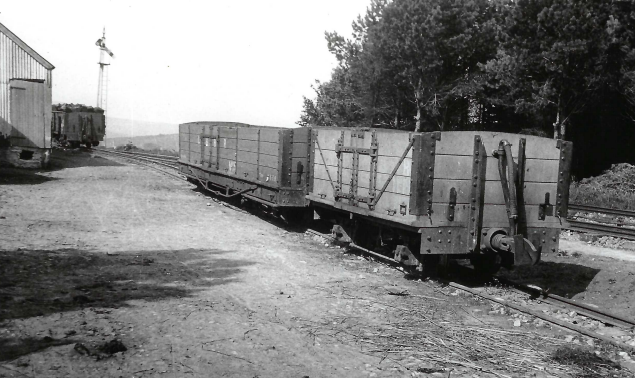

The scout remembers entering the yard, then used by a building firm or a builder’s merchant, in the early 1970s with his Dad, who went to the office and obtained permission for the lad to look around. The carriage and engine sheds were still standing, and the inspection pits between the rails were still there. At the neck of the yard, where the line went towards Lynton, the point of the triangle was undisturbed and fenced. The scout looked through the chain link and saw, or remembered seeing, little sleeper impressions in the ballast. But was that possible, 35 years after closure?

The scout cut through to Princess Street and entered Central Business Park, where he was able to look over the fence at the course of the line behind the houses in Yeo Vale Road.

Derby Lane Bridge (No. 6 in Southern parlance)

Raleigh Weir (Bridge No. 8)

Beyond the weir, the course of the line is in open countryside, which would be largely recognizable to old passengers, were any still alive.

On the train to Exeter in the evening, the scout chatted for the whole journey with a doctor at the hospital. She cycled from her home in Exeter to St. David’s and from Junction to the hospital in preference to driving.

The scout learnt more about the N.H.S. and modern doctors’ lives. Her advancing had meant 12 postings in 10 years. In turn, she learnt a little about railways, including the folly of not electrifying the system by the 1970s, the absence of freight and small goods, and the greatly depleted network. She was enlightened as to what powered her train to work. She was using a Devon & Cornwall railcard, rather than a season ticket.

Her salary was £55,000, she volunteered, which caused the scout loudly to point out that the train driver was earning the same, or more.

On 11th September, the scout rode through Barnstaple’s housing sprawl to reach Goodleigh Road, which, after climbing steadily, drops to the Yeo Valley.

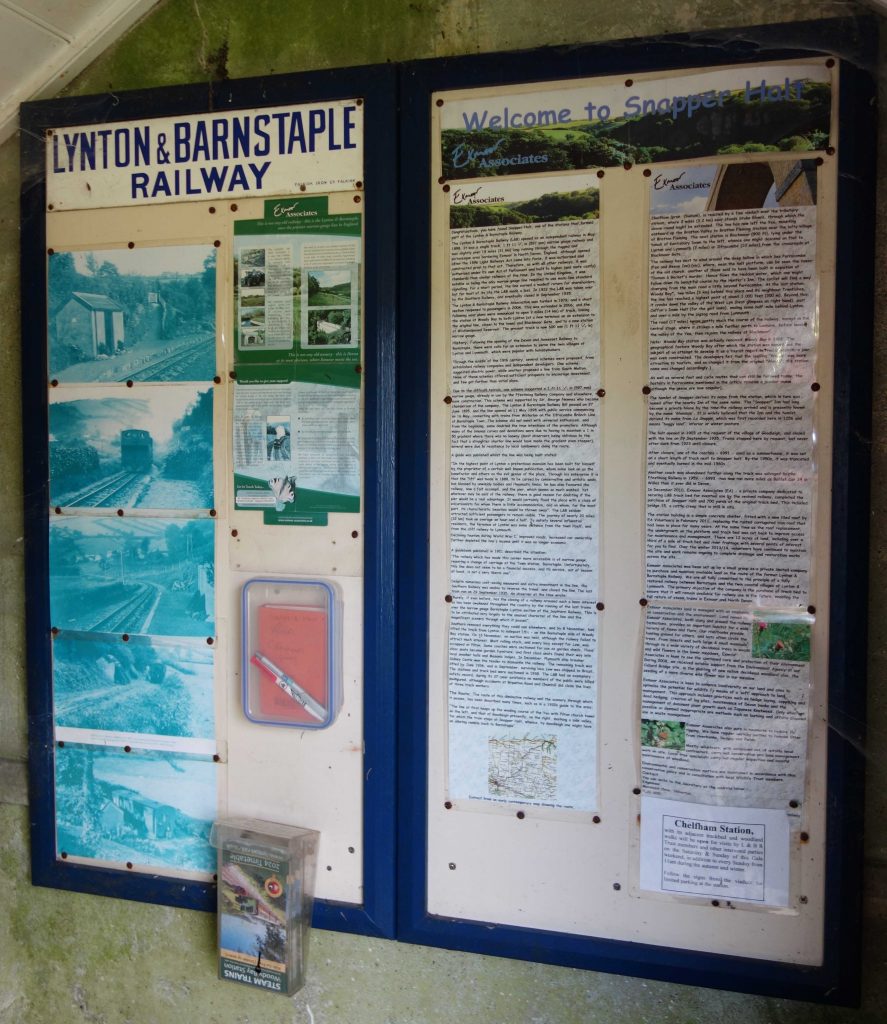

Snapper Halt

An account of a visit to Goodleigh and Snapper in 2019.

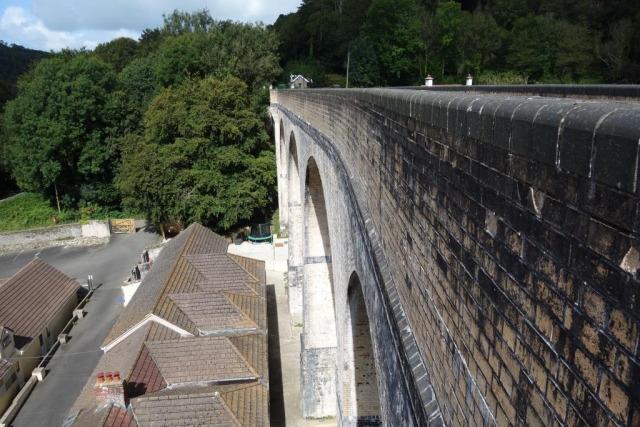

Collard Bridge (No. 18)

Skew Bridge (No. 19)

Shamefully, on his 11th of September ride, the scout passed the bridge site without stopping. He caught the excavations from the corner of his eye, but was looking for the council road depot which he remembered as being more obvious. As the day went on, he was to learn more.

Bridge No. 21

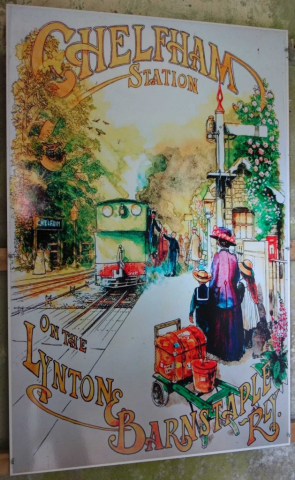

The scout walked along the track towards Chelfham and saw men in orange ahead. He approached them and found that they were Nigel, the esteemed S.M., Chelfham, and Ian from the Mid-Hants. They were doing a bit of clearing and had crossed the viaduct to reach the site. The scout asked Nigel if he’d take some photographs when he returned, which he was about to do.

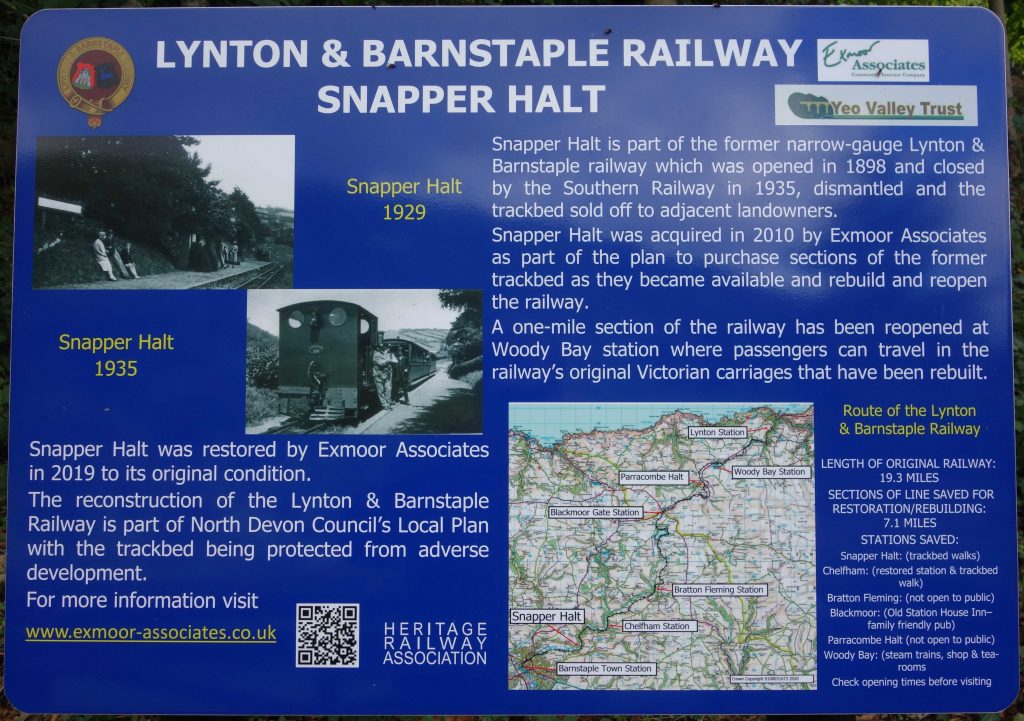

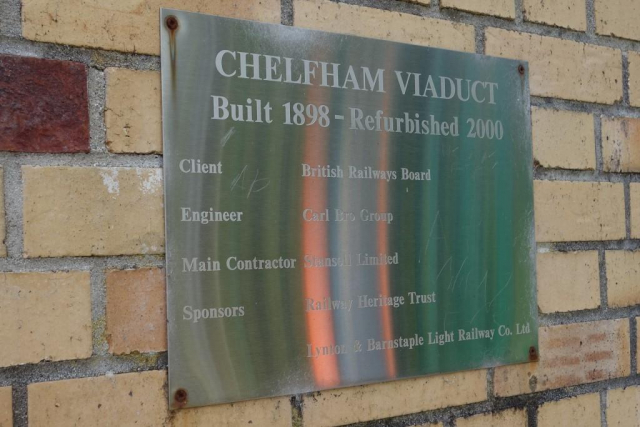

Chelfham Viaduct

Chelfham

Even as a long-serving railwayman (B.R. 1974-1995; Teign Valley 1975 – ), the scout was not permitted on the viaduct and so made his way around by road to the station.

Tradition was upheld on his arrival and the gang stopped for tea on the Down platform. The scout tucked into the lunch that he’d bought at the Co-op by Derby Lane Bridge.

Naturally, the management of the railway and its future were discussed; the scout tried to foment unrest with talk of Chelfham declaring independence, but the L. & B. is a united organization with one ultimate ambition.

Andy, an E.A. member, who had been feverishly mowing, joined the tea break. He was going on to Bratton Fleming and offered a lift to the scout, who was only too glad to accept it, as he had rather felt that his ride, as in 2019, would get no further than Chelfham.

Building a length of working railway at Chelfham, like that at Woody Bay, would be possible; it could also be done between Blackmoor and Wistlandpound. They would be good for morale and it might be that joining the operations together became a driving force. But would two or three separate lines be efficient and remunerative? Would all but enthusiasts just have a ride on one?

Brattton Cross Bridge (No.24)

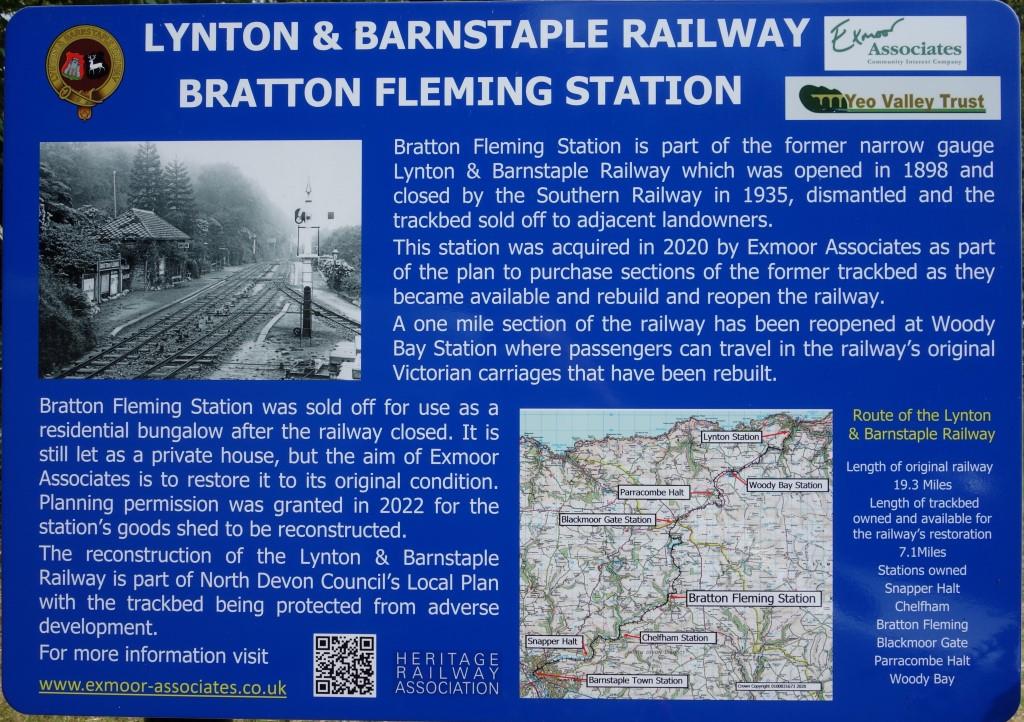

Bratton Fleming

After showing the scout inside the station building, vacated by its former tenant, Andy said it would take him about an hour to mow the grass.

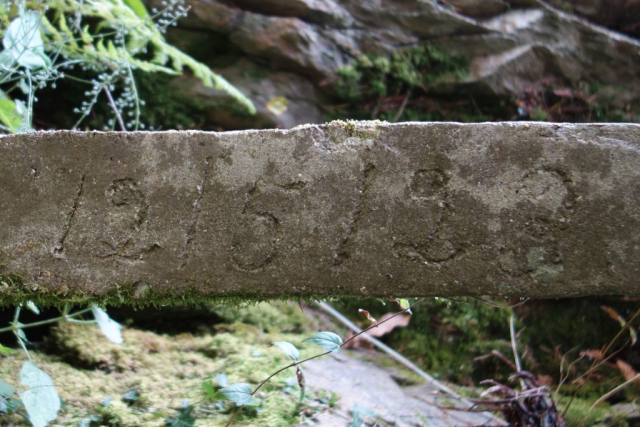

On the way back to Chelfham, Andy told the scout about the digging he had done at Skew Bridge, after a line of stones had been found parallel with the line. the scout promised that he would stop and view the work, which it can be seen that he did from the photographs above.

On his ride in July, 2025, the scout met a lady with a dog who was able to answer his questions about the village. The scout was reminded of newspaper coverage of the planning applications made by the owner of The White Hart, who claimed that the pub was unviable. The lady talked of plans to take it over as a community pub and incorporate the shop and a Post Office counter. She told the scout that the Sports Hall had closed when the lease was up and there were complications. She said she would be delighted to see the railway reopen and spoke of the work that had been done along the line. The scout told her about the opposition in Parracombe and its principal troublemaker. She rolled her eyes and said that she and her husband had worked for Gold Blend and had found her impossible.

As he was chatting, a South West Water officer came up to seek information about the area from someone knowledgeable. The scout quipped: “You’ve found her.” He was arranging to conduct a survey on the water course that is used to bring water from Wistlandpound to the treatment works at Bratton Fleming. He would be looking at the idea of discharging water just to replicate the natural flow that had been interrupted by the reservoir. A study of the life in and along the water course would take around four years.

After the lady went on her way, the scout continued conversing with the young fellow whose home was in Wimborne Minster and whose area stretched from Bournemouth to Penzance. The subject of runaway infrastructure projects was broached, which naturally led to the new London and Birmingham. For not knowing to the nearest decade when it will open, and to the nearest £10-billion how much it will cost, this public spending orgy would have to take the victor ludorum. The latest troubleshooter had found failings in governance that he promises to fix, which is just what his predecessor said a few years ago.

In the ordinary, day to day sphere, nothing and no one have been spared from cuts: old folk, those with special needs, youngsters, buses, libraries, national parks, lollipop ladies – the lot.

With the high speed railway’s billions, there could have been a thousand – maybe ten thousand – smaller projects delivered which would have brought real and more immediate benefits to whole swathes of the population. Flippantly, the scout suggested to his friend from the water board that the L. & B. could be rebuilt – or certainly parts of it – under such conditions as a “good works” sideshow.

At Button Hill Bridge, No. 35, the scout was reminded that he had been invited by David Moore to visit his length of line in 2019

The line sweeps around in a semicircle to cross the same road at Lower Knightacott, but the overbridge here, No. 38, was long ago demolished.

Narracott Bridge, No. 39

After the railway had closed and its land had been handed back to the original owners, the farmers at Narracott, Sprecott and Hunnacott must have made its course into a road, but how this became adopted by the council as a right of way is not known.

Wistlandpound

The reservoir, built in 1956, supplies Ilfracombe, Combe Martin and Barnstaple. Its earth dam took some of the formation of the little line and more was flooded.

Blackmoor

When the scout rolled up to what is now the Old Station Inn, he thought that it was closed. The front door was shut, there were only a few cars and no one was sitting outside. Thinking about where he might go for lunch instead, he went close to the glass door and saw someone sitting at a table.

He pushed his bicycle to the doors opening onto the garden and found them open. A lady served him a pint of lager and took his order for a bacon and brie baguette, which he said he would eat outside. The place was near empty.

The baguette came with coleslaw, a bit of salad and some crisps. With another pint, the bill came to £25, vastly more than the scout would normally pay for lunch. But the L. & B. own the place and the scout considered that he had helped the cause.

As he was reading Railnews and eating some couples, and chaps who had come in vans and suchlike, enlivened the garden with chatter, which the scout tried hard to overhear. No one ordered a meal and it appeared that one drink per patron was enough.

The scout took his empty glass and plate back to the bar and asked the lady: “When does it get busy.” Her face told the scout that it didn’t. Trade had been worse this year so far than last. “Everyone’s struggling,” she said, adding a reference to the cost of living. She was happy for the scout to take some photographs.

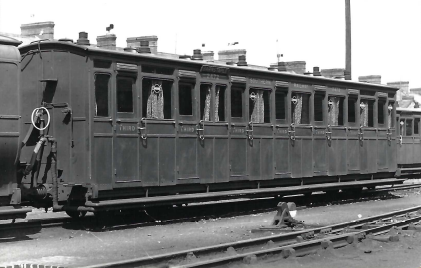

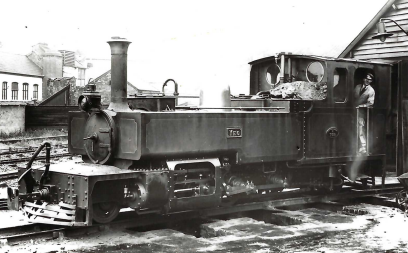

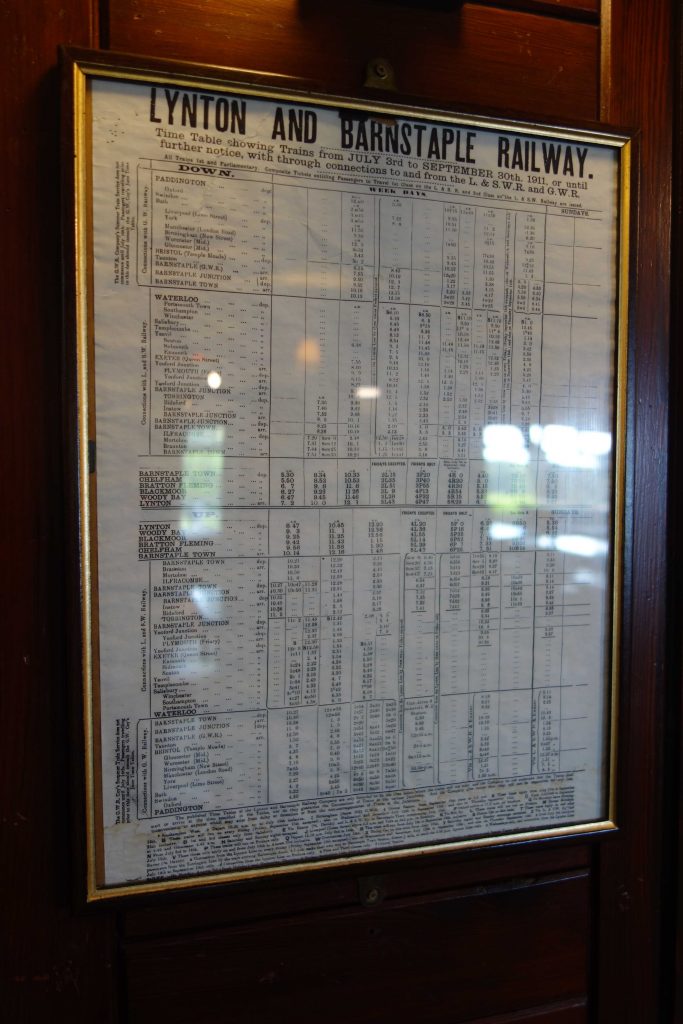

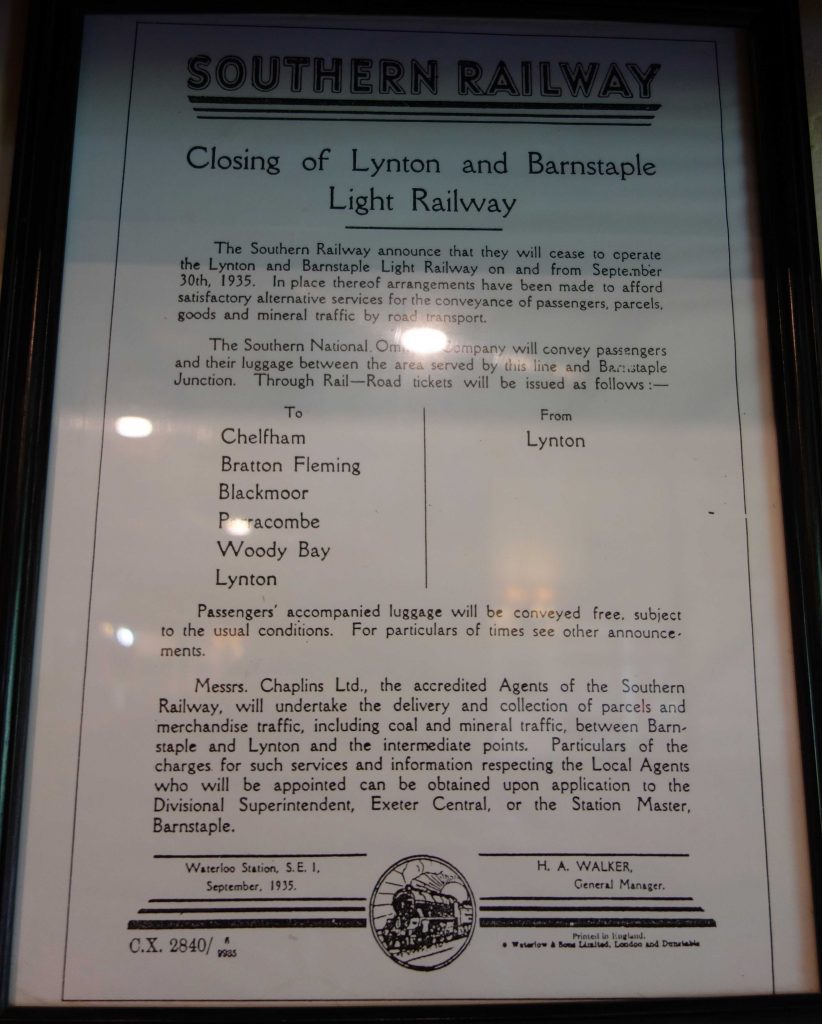

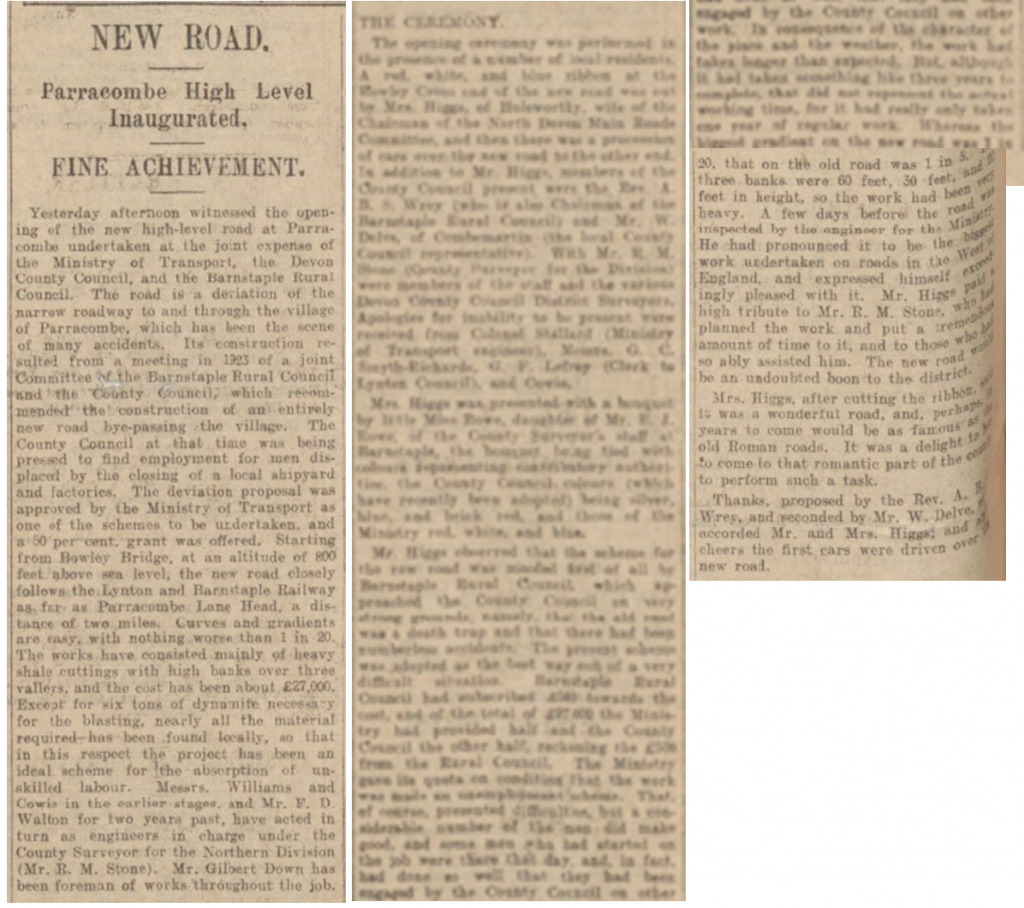

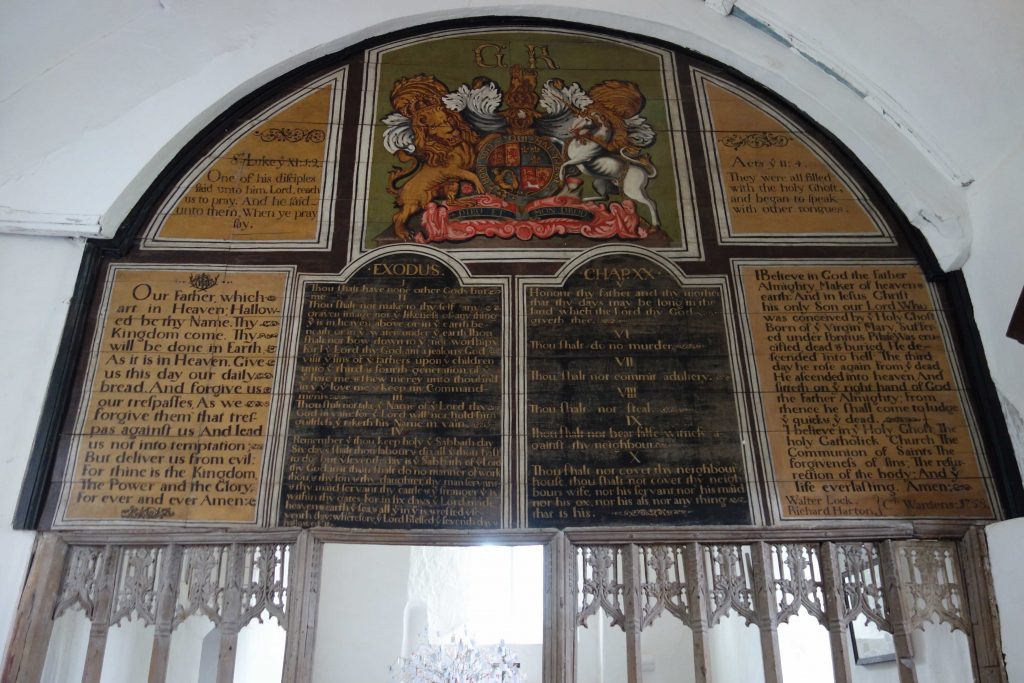

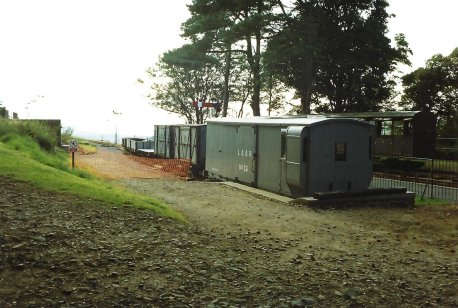

The scout snapped these frames hanging on walls as best he could.

The buses were sold to the G.W.R. in August for the inauguration of the service from Helston to Lizard, which is where they are seen in the photograph.

In June, 2025, following Exmoor National Park’s refusal of a planning application to extend the line to a site just short of Parracombe, L. & B. members were presented with a list of options and asked to choose the one that they wished the trust to pursue. Detailed were ideas of extending from Woody Bay or the present end of the line at Killington Lane, and of starting anew at Blackmoor or Chelfham.

A line from Blackmoor to Wistlandpound would allow passengers to walk a mile and a half around the reservoir. It is unlikely that such a line could justify steam traction and so it could become a showpiece electrified narrow gauge railway using power generated locally by the wind or sun. It would give bus users easy access to the lake and would bring more custom to the inn.

Parracombe

Killington Lane

Coverage of the “Temporary Terminus” here is presented in video form.

A lone passenger told the scout that he was from Newcastle upon Tyne and that he had lunched in the Fox & Goose, about a mile from the station. He wondered why the course of the line between Killington Lane and Parracombe Lane had not been made into a permissive path, which would reduce the distance to the shop to about half a mile and would make it about three quarters of a mile to the pub.

Woody Bay

Caffyns Halt

Lynton & Lynmouth