Viewing the new £40-million* D.M.U. maintenance depot nearing completion at St. David’s brought back memories of Newton Abbot’s diesel depot, the ruins of which the scout scavenged.

From the general purpose to the monofunctional

The new work occupies the sites of the goods shed, the goods office and sidings which were part of the station’s only yard before Riverside was opened in 1943.

Beyond lay the carriage chutes, cattle pens, cartage stables and cottage, part of the goods avoiding lines and the locomotive shed, with its coaling stage and turntable.

This depot has been built for passenger trains alone and no provision has been made for the general purpose system that will surely be needed if the railway is to contribute fully to decarbonization and other pressing challenges.

As it is, not a single modern manager will be ashamed to admit that all the fuel, supplies and parts, and even on occasions the trains themselves, will come by road.

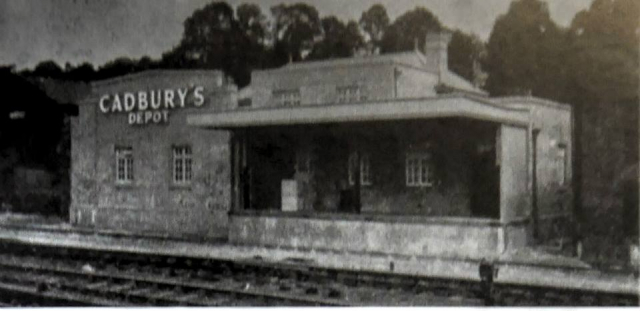

Why would Cadbury’s have a rail depot?

On this side of the line, there are further reminders of the diverse transport services once provided by the railway.

Behind lay a string of other rail-served stores and New Yard, which provided additional capacity for station-to-station traffic. Beyond that was Henry Norrington’s oil store.

Before the camera, to the left, lay the yard of Ward & Co, coal and general merchants, and other stores, including Joe Lyons’. At Red Cow Crossing was the road vehicle weighbridge. The car park is still called “Ward’s.”

Newton Abbot (NA, 83A)

Newton had a locomotive shed very early in South Devon days and this grew to be a principal installation on the Great Western, with a repair shed and C. & W. workshop.

In 1962, the repair shed – “the factory” – was converted for the new diesels, with four roads, each having inspection pits and cab-level platforms, and the whole area being served by overhead travelling cranes. A new traverser, fuelling point, D.M.U. servicing facility, carriage washing plant and traincrew block were built.

The factory lasted all of eight years and the whole of the depot was closed by 1981.

The scout remembers getting a footplate ride on a Class 45 from the depot to St. David’s, a regular light engine movement, in 1978. Behind the window in the traincrew lobby, the clerks – roster, paybills, stores, timekeeper – were busy at their desks and men were coming and going. Upstairs were the mess, locker room, washroom and toilets.

The scout became very familiar with the increasingly derelict place, when, in 1985, armed with a “redundant assets” chit, he began taking away lots of useful equipment and materials, aided by the railway’s utilicon being able to get into the buildings.

He remembers particularly the constant cooing of pigeons on the roof trusses, everything being covered in droppings and an odd effect of the rooflights being broken. The floor in the unmodernized parts of the building was made of what could have been offcuts of wagon floorboards, or sawn up old floorboards, laid end-grain up. Black with oil, when wet the floor rose into hillocks; some broke up and others held their shape.

Today the factory is occupied by Teignbridge Propellors, certainly a worthy engineering successor, while most of the rest of the complex was demolished to allow the development of a trading estate. An effort was made to preserve the wagon repair shop but this was destroyed by arsonists in 2018.

The last haul, gifted by the demolition contractor, recovered and taken to Christow, was a pile of rails, including some 60 lb. bridge, in 2002.

* £56-million, when all reckoned up, according to Today’s Railways.