The scout would have seen the feed store many times from the train but it was not until he became aware that the site was to be sold that he went to have a closer look. It was then that he thought the old store could well become the Building Department workshop at Christow.

The feed store, seen at right, and the cattle pen on the edge of the picture, were served by the line which passed through the goods shed. The passenger station, closed in 1959, was a quarter-mile Up the line (to the left).

The feed store was used by E.C.C./E.C.L.P. in connection with the loading facility.

Copyright: Michael L. Roach.

After years of dormancy, fate would have it that when contact was made with the B.R. Property Board on 13th January, 1993, the order had just been given to a local builder to demolish the shed and use some of the material to patch up the goods shed.

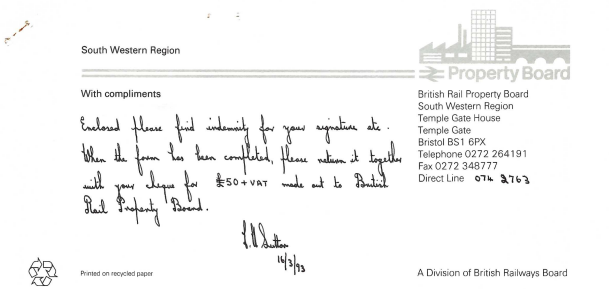

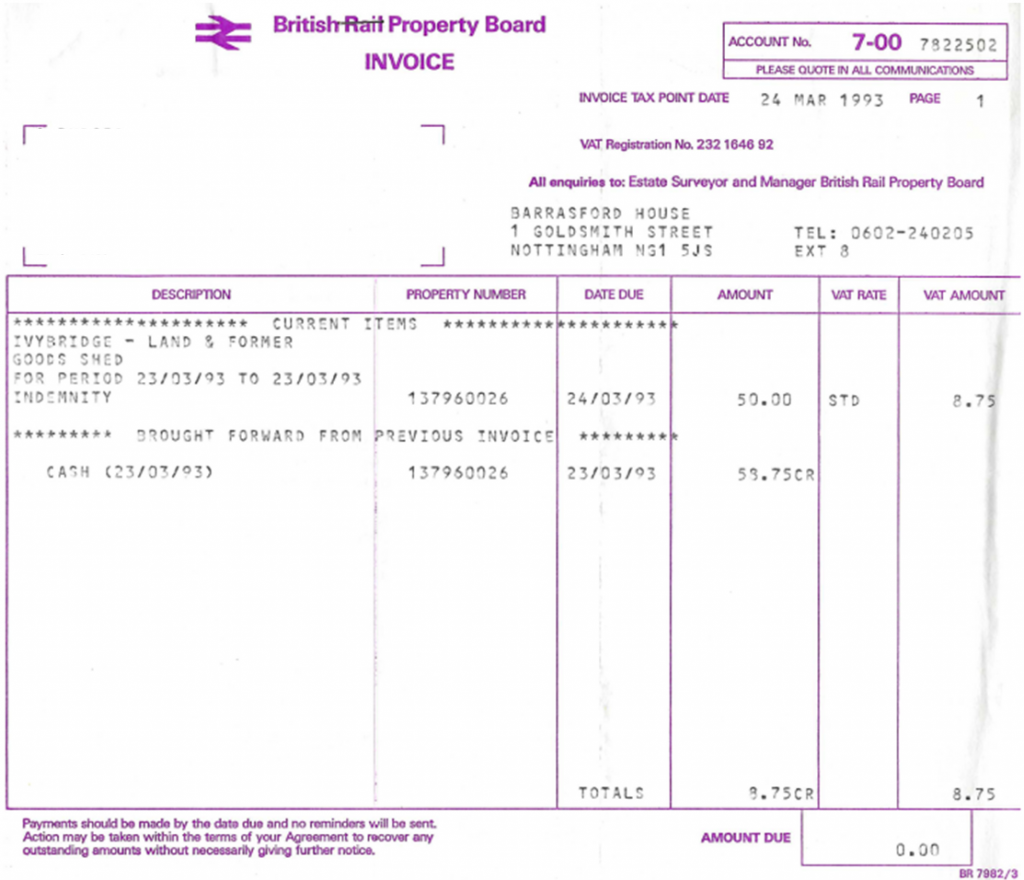

Fortunately, the officers responsible were amenable to the old store being sold and a day later the Works Surveyor, Mr. Sutton, instructed the builder to take his own materials; he had been about to go to the station when the order was received. On 22nd, Mr. Sutton advised that the main shed had been secured using secondhand materials costing £50.

On 5th March, Mr. Wilmoss, the Area Surveyor, agreed to the sale and raised a charge of £50 plus V.A.T.

A building commonly found at country stations was the feed store, from which proprietary animal feeds and supplements would be dispensed to local farmers. Usually, a small store like this one would have been managed by the railway on an agency basis. Stock would be unloaded and sales entered up by railway staff, transactions being periodically checked by the firm’s representative. At many stations the railway would also be the carter.

“There were animal food stores from which local agents sold to farmers. The food arrived in bulk and was delivered by railway lorry or the agents used their own transport. Some farmers collected their own feedstuffs.” Cliff Carr, L.M.S. Station Master, from Life on the Old Railways by Tom Quinn.

The beauty of the railway’s method was that it took these commodities near enough to the point of demand that they could be handled by light road transport.

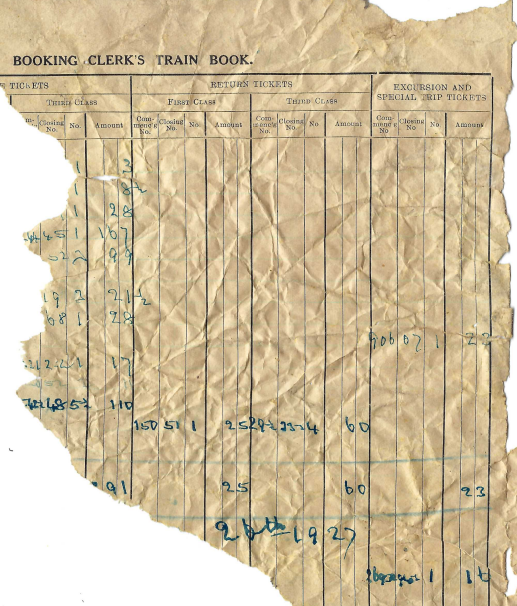

This building was put up at Ivybridge by the G.W.R. around 1930. A page from the station’s ticket issue book dated 1927 was found stuffed behind the lining.

The building stood on brick columns so that its floor was at platform level; it is thought that it formerly rested on a timber framework. A canopy projected from the platform side. It was clad with 18-gauge corrugated iron and had decorative bargeboards and finials. Every aperture was sealed up to keep out vermin; even the hungriest rat would tire of chewing through a three-inch floorboard.

The timber-framed building had been used as a den by local youths, who must have started fires deliberately or by accident. Still, the structure was largely sound and remained so after someone else started a fire with a cutting torch.

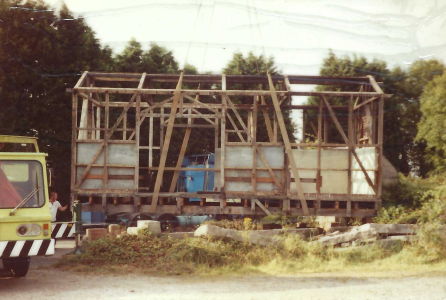

It was decided to scrap the 18-gauge cladding. Most of the heads of the fasteners were blown off using a torch. The four, heavy canopy brackets were dropped to the ground. Having to take the gas bottles and tower scaffold to the site limited what could be carried back. In all, ten trips were made and all the cladding, timber platform, brackets, doors, etc. were brought back to Christow. The building was braced internally to counter the inward thrust of the lifting slings and for the move.

The doors on the road side were missing. The pair on the rail side was taken to Christow and then left in a non-railway store. Eventually, they were left outside on the ground and became rotten. The store, if it is ever repaired, will have sliding doors or roller shutters and so the original doors would not have been re-used. They could not open outwards because the platform is too narrow; opening inwards would have taken up at least three square yards of floor. It was only when they were returned to Christow that it was noticed that the stiles had been cut, meaning that the 7′-4″ x 4′-2″ doors had once been 10 or 11 feet tall.

The building had been painted in E.C.C./E.C.L.P blue.

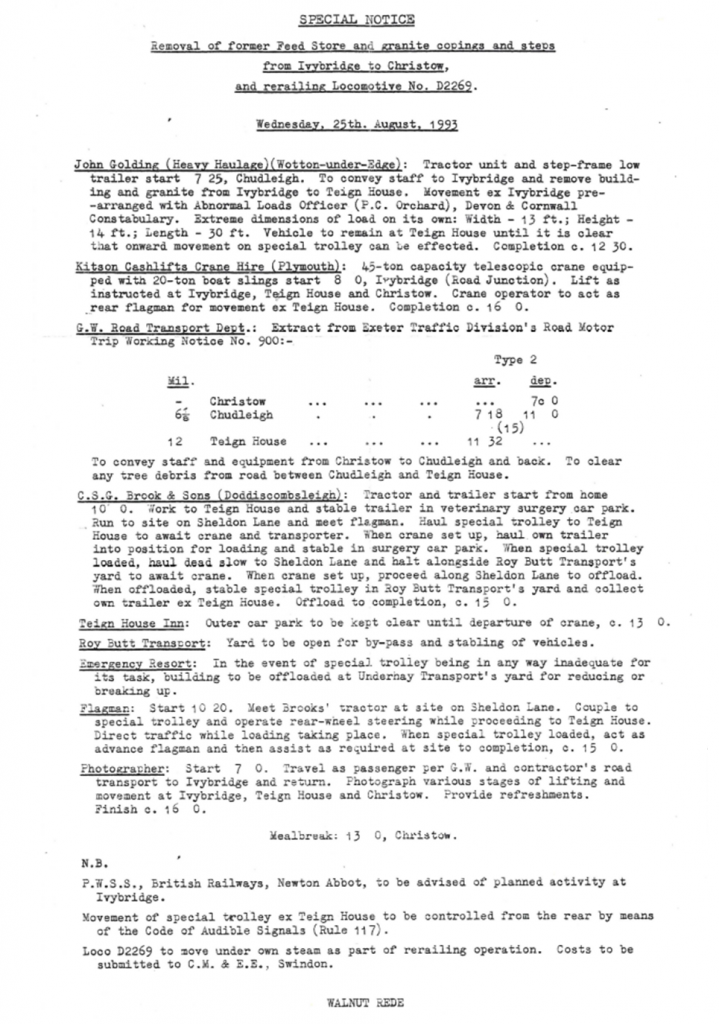

The utilicon departed Christow, 0701. Chudleigh a. T, d. 1245; Teign House a. 1410. +

The timber frame measured 30 ft. x 13 ft. and was 14 ft. to the ridge. A very low trailer would be needed to carry the building in one piece. Such trailers generally have little ground clearance, but John Golding of Wotton-under-Edge had one with small wheels beneath the bed and the heavy haulier agreed to do the job.

At Christow, a foundation was prepared for the building. The remaining wall of the concrete hopper was left with the intention of it becoming a platform. The building would be positioned a set distance from the edge to allow for the canopy and a set height from rail level.

Movement beyond the Teign House crossroads would have been impossible using the low loader. Fortunately, a trailer was found in Gorman’s scrap yard in Newton Abbot and this was brought to Christow by Roy Butt Transport. Even this would not negotiate the tight turn onto the station bridge, whose parapets are 15 ft. apart, and so the rear wheels were cut off and made into castors linked by rodding. A tiller was attached to the left hand castor.

When the member of Teign Valley staff rendezvoused with the lorry on the slip road of the Chudleigh Station junction, he groaned. It would have needed a feeler gauge to measure the ground clearance of the well-frame trailer that had been sent and it was far too long and unmaneuverable. The driver told him that the booked trailer hadn’t come back from Ireland.

There was nothing for it but to continue and try not to think about what was bound to happen.

The whole day’s arrangements depended upon the building being sound enough to be lifted. In the event, the four-ton ruin came off its bearings without a creak or a groan. The fun started later.

A feature of one of the lengths of the Teign Valley road that was adopted by the turnpike trust is the hump at Whetcombe. If there were any thoughts that this may not have been such an obstacle to a low-slung trailer, these were dispelled when it grounded on the camber of a roundabout in Ivybridge. The driver leapt from the cab, fired up a donkey engine and lifted the neck of the trailer enough to move.

There is only one form of land transport that could move this sort of load.

The driver has taken advantage of the slip road to pull to the left. The lanes are about 12 ft. wide.

He had made the usual mistake by saying: “This is going well.”

By chance, the lorry is almost directly above Marley Tunnel.

The rig stopped on the exit slip at Chudleigh Station to await police escort for the run up the valley. More than one and a half hours passed before the constable arrived, during which staff agonized over the work yet to be done and the people standing by at Christow.

At Crockham Quarry, the lorry driver went forward with the constable to inspect the hump. They returned with glum looks but agreed that there was little option other than to carry on and hope for the best.

This was a length of existing road adopted, not built, by the turnpike trust c. 1830.

Even if there had been a speed which would have enabled the trailer to have been slid over the hump, it would not have been possible because of the short approach. And there would have been the risk of damaging the fifth wheel.

So the trailer grounded firmly on the hump, where the road is only 16 feet wide (It may not have been as wide as this at the time because subsequently work was done to stabilize the road). By now it was gone midday and aimless trippers were out looking for places to lunch. A queue of traffic soon built up in both directions. Some cyclists were just able to get past by holding their bikes over the crash barrier.

By the greatest of good fortune, behind the trailer was a large agricultural tractor. The staff member stood on the back of the trailer holding vertical the heaviest sleeper he’d ever lifted, so that the tractor could “buffer up.”

At first, nothing happened: the tractors great wheels slipped slowly. Engine revving could be heard from the front. Eventually, the trailer budged and was over the hump. Four impressions in the tarmac remained for years afterwards, marking the spot where assistance from the rear had been given.

More fun lay just around two bends in the road. The second leads directly onto Doghole Bridge over the Beadon Brook, what the railway was later informed was the narrowest point on the road; actually it is also about 16 feet.

The driver made the best approach possible but as the load passed over the bridge, six granite copings on the downstream parapet, and then seven on the upstream side, were displaced, with some falling into the brook.

Just beyond, there was room for traffic to pass. In the queue was a Devon County highways officer, who took names and addresses, gleeful that he had caught in the act someone responsible for a bridge strike (The Bridge Engineer later told the railway that out of 15 cases on his desk, he had only traced the parties responsible for two).

Where it had originally been thought there would be difficulty was the bends at Ryecroft, but these were negotiated without incident and the load was soon blocking the crossroads at Teign House.

While the building was left outside the neighbouring yard, which traffic could pass through, the tractor went back for the granite. When this was offloaded, the building was moved into position for its last lift.

Apart from the broken coupling and the very late running, the final part of the move went as planned and there was satisfaction in proving wrong the idle wiseacres at the pub who’d said it couldn’t be done.

However, the fun didn’t end with the building being put on the ground. The railway’s diesel shunting loco had been delivered in April but the booked crane had broken down and the substitute was only able to offload it at the entrance. It was later driven down the slope on the dirt. This was the same crane and the move depended on the loco being able to travel between the two lifts necessary to rerail it.

It was essential to start the engine because the loco had to be driven along the ground again. The old six-volt batteries were nearly flat but using the decompression levers allowed the six-cylinder Gardner to be cranked.

The crane swung the loco through half a turn and placed it so that it could be driven about thirty yards to the end of the line as it was then. This went as planned but then the crane got stuck in the ballast and the driver had great difficulty positioning himself close enough to the loco to be able to lift it. He wrestled with the controls but finally stopped and folded his arms in despair. “What about draining the fuel?” he said. The lads at Western Fuels had generously filled the 125-gallon tank with gasoil.

Draining wasn’t necessary and no one remembers what was done, only that the loco did get rerailed and the two old boys who had been helping and who had both travelled on the branch, were like boys again. Gerald, the one in the cab, remembered going off to start his National Service in the winter of 1947 when only the trains were moving.

Some shots went off under the wheels to celebrate the first loco at Christow in over thirty years and what was thought to be the first ever diesel.

It was to be nearly thirty years before proof was found that Perseus was not the first diesel locomotive to reach Christow.

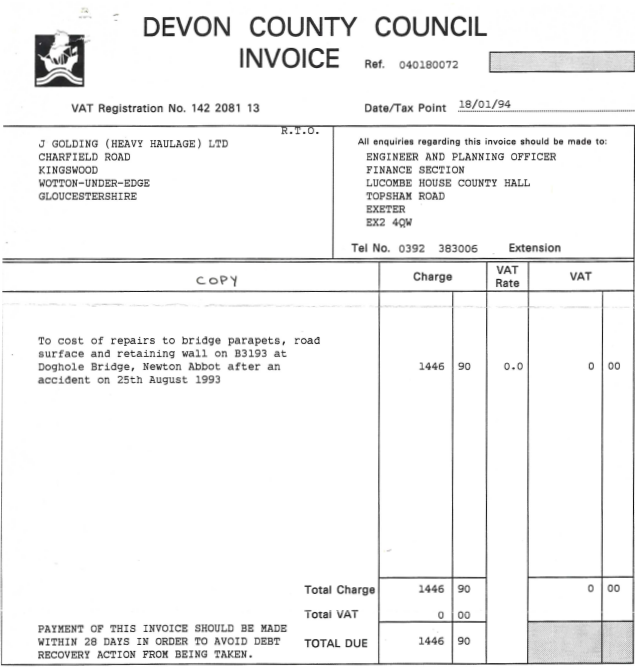

Doghole Bridge

The first estimate of the cost of repairs to the bridge and a retaining wall was £2,000. It was claimed that 11 cubic metres needed rebuilding. Putting right damage to verges and bollards was estimated at £200.

Hire of the lorry had been a cash job and the understanding was that the railway would pay for any damage to property. But the haulier hadn’t supplied the agreed type of trailer.

The railway offered to repair the bridge but the county would not allow this, citing many conditions that only an approved contractor could meet.

It was strictly the haulier’s liability and the railway’s solicitor informed Golding’s that the firm would have to make an insurance claim. The railway agreed to pay 10% of the amount to cover any future loading of the premium.

The matter was settled at the end of January when the railway sent a cheque for £145. Thanks to badgering by the railway, the county had in the end not charged for all the work that was done.

Costs

When it was reckoned up, the whole operation cost £1,474.83. This included all the preparations; hire, transport and conversion of the special trolley; hire of the lorry, crane and tractor; payment for damages; and legal fees and gratuities. The Teign House Inn was paid £40 for loss of custom, although it looked as if drinkers had actually gathered for the spectacle and to see a railwayman fail.

Did the Feed Store become the Building Department Workshop?

The intention was to make the building into a spacious workshop which would look like it belonged at Christow.

The structure was to have been repaired and the canopy brackets refitted. It was to have been roofed in artificial slate or corrugated steel and the walls clad in steel or timber. New doors and windows were to have been made and the building fully insulated. The platform wall was to have been faced and the ground made up around the building.

Sadly, all that was done was making a temporary roof and cladding the structure in plastic sheeting. In this form it has been a useful store and many items have been worked on in the covered space.

For nearly 25 years the Site Office has been the workshop and it is adequate for most jobs. It can be kept warm very cheaply. The purchase of a movable combination woodworking machine reduced the need for more space.

But, if only for the sake of appearance, the new workshop will one day be finished.