The scout had ridden from Okehampton to Barnstaple in 2019, the last year of the summer Sunday service. He had followed the route, wholly or in part, on many occasions, most recently in 2021 after riding the Torrington turnpike from Morchard Road, but had never photographed all of its features.

Bonhay Road in Exeter was quiet as the scout headed for St. David’s to catch the 0810 to Barnstaple, but a motorist still felt compelled to draw alongside him and call through the passenger window, dispensing advice about where to cycle. A little further on, the red car was spotted pulling out of a turning to the left; the driver went back in the other direction and parked. The scout looked at his handlebar clock and then crossed over to confront the silly fellow with: “DON’T ****ING SHOUT AT ME THROUGH THE WINDOW OF YOUR CAR EVER AGAIN!” Suitably told, the fellow quietly asked that the scout use the cycleway, to which he replied: “No!”

To be clear, a length of pavement on Bonhay Road has been marked as a cycle lane. It starts where it is least needed and ends where it is most needed and is far from adequate in between. The only time the scout uses it is when he hears a lorry behind him.

The 0810 has long dwells at Crediton and Eggesford to await paths on the single lines and takes 78 minutes to cover the 39 miles, an average of 30 m.p.h.

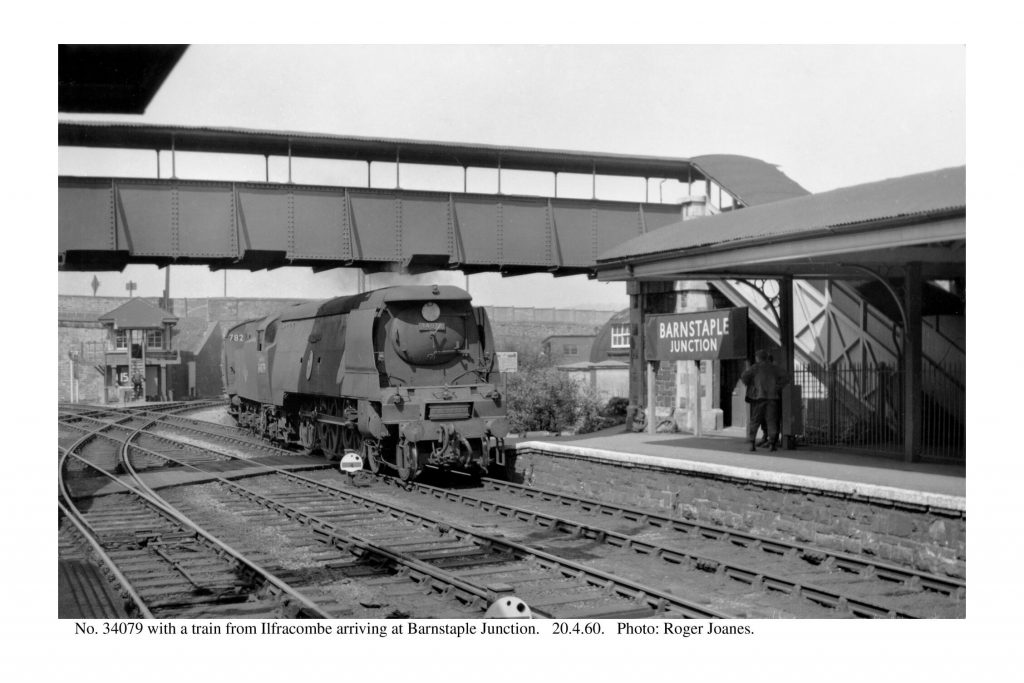

Barnstaple Junction

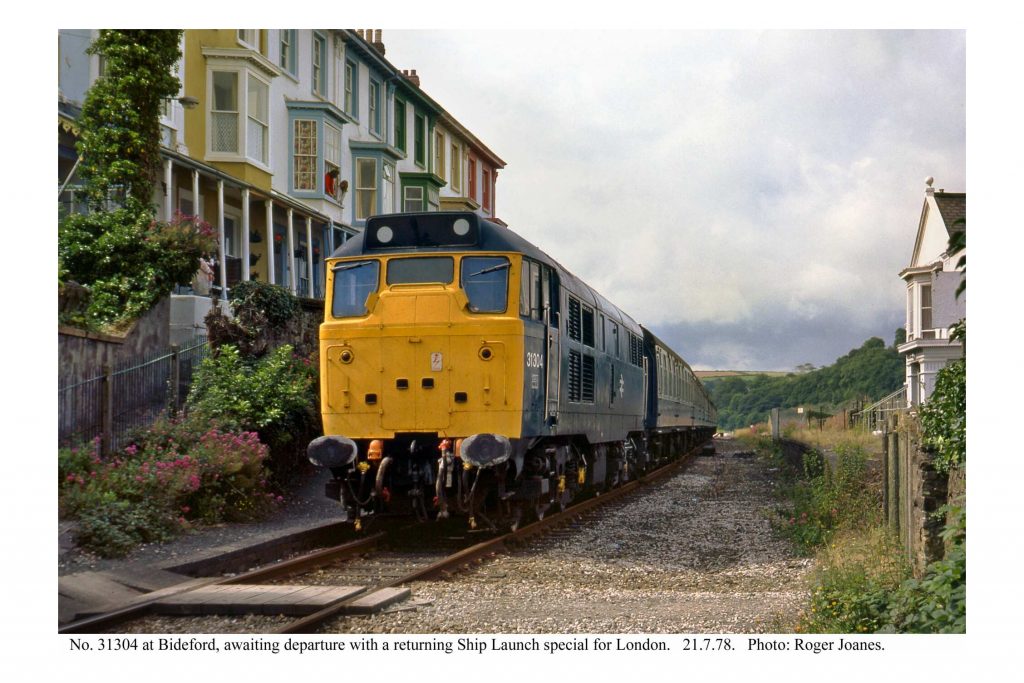

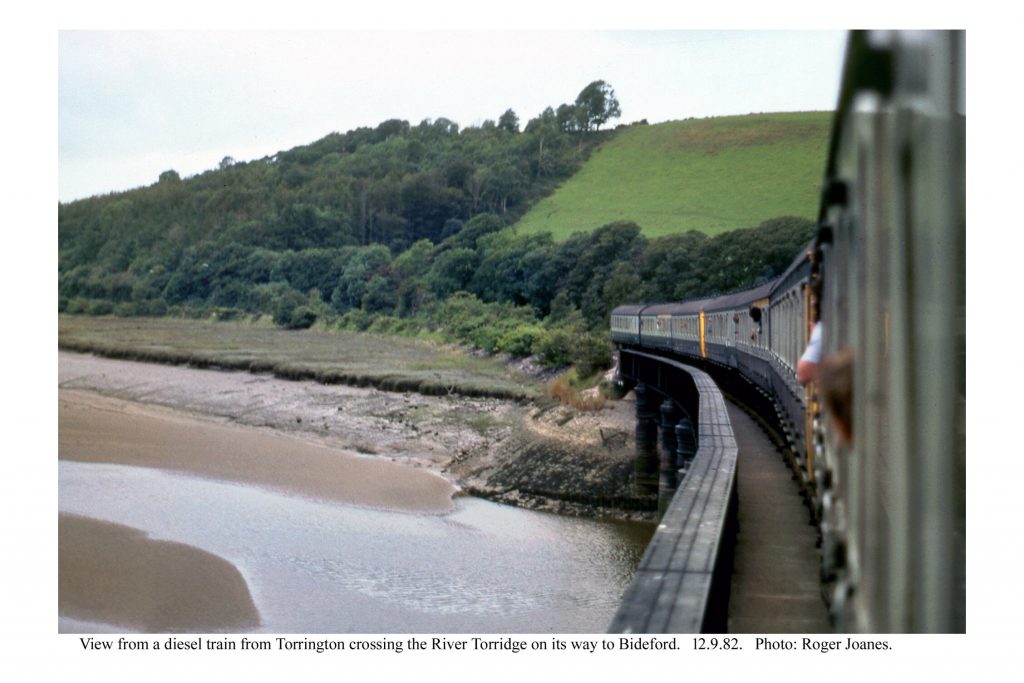

The scout also remembered the day in 1982 when he stood behind the driver of a Class 31 setting off from the former Down platform (2) to Meeth to collect clay wagons which would never be loaded again from there. It was a move which the scout had arranged to coincide with his rest day and the Driver working the turn being asked beforehand if he’d mind having a footplate passenger.

In the event, four more were on the loco: the Secondman and P.W. Chargeman in the leading cab and the Guard and Shunter in the rear cab.

The viaduct ahead spans a busway and footpath from the truncated Sticklepath Hill and was supposed to allow for a reinstatement of the line to Bideford through the centre span.

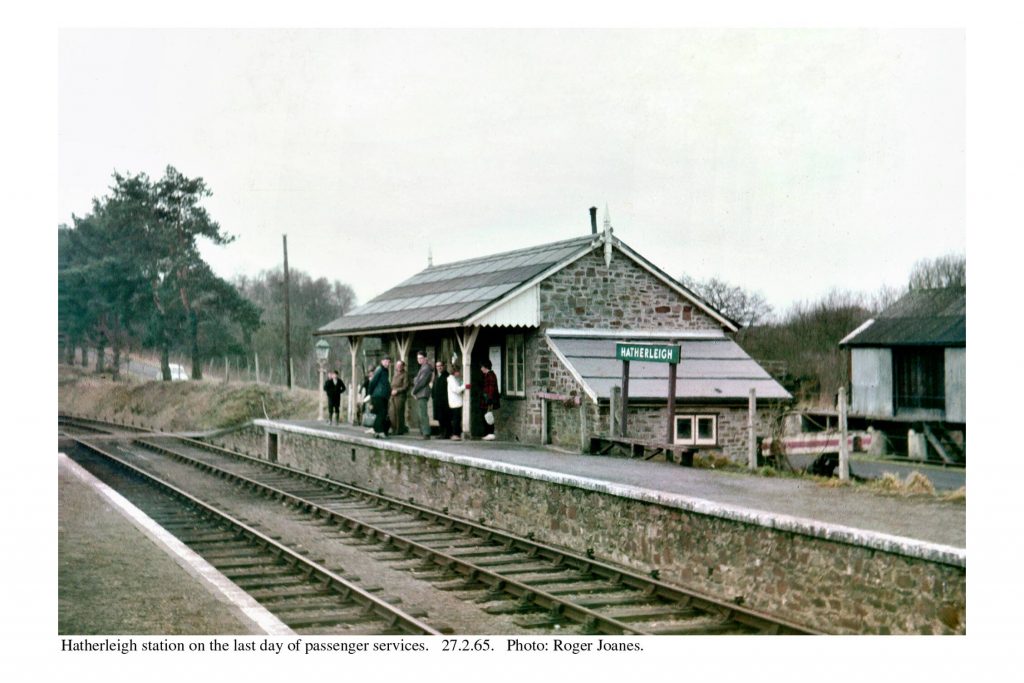

Copyright: Roger Joanes. Shared under Creative Commons. +

In a now out of print pamphlet, the scribe had likened Barnstaple to a railhead on the American frontier where a hoss could be hired to take a rider on over the barren prairie. On this occasion, the scout went to the “stables” to buy some chain oil. There was none for sale but a fellow was kind enough to lubricate the dry derailleur. He was expecting a coach party, for which he had bikes ready.

The scout was here on 24th May, 2007, the day after the new downstream bridge was opened by Councillor Brian Greenslade.

He was locked up in 2021 after being found guilty of committing sexual offences. The commemorative plaque has since been officially defaced. The rostrum used in the ceremony is seen at left.

The groping councillor admitted some years later that the bridge would not be a lasting answer to Barnstaple’s motor traffic problems.

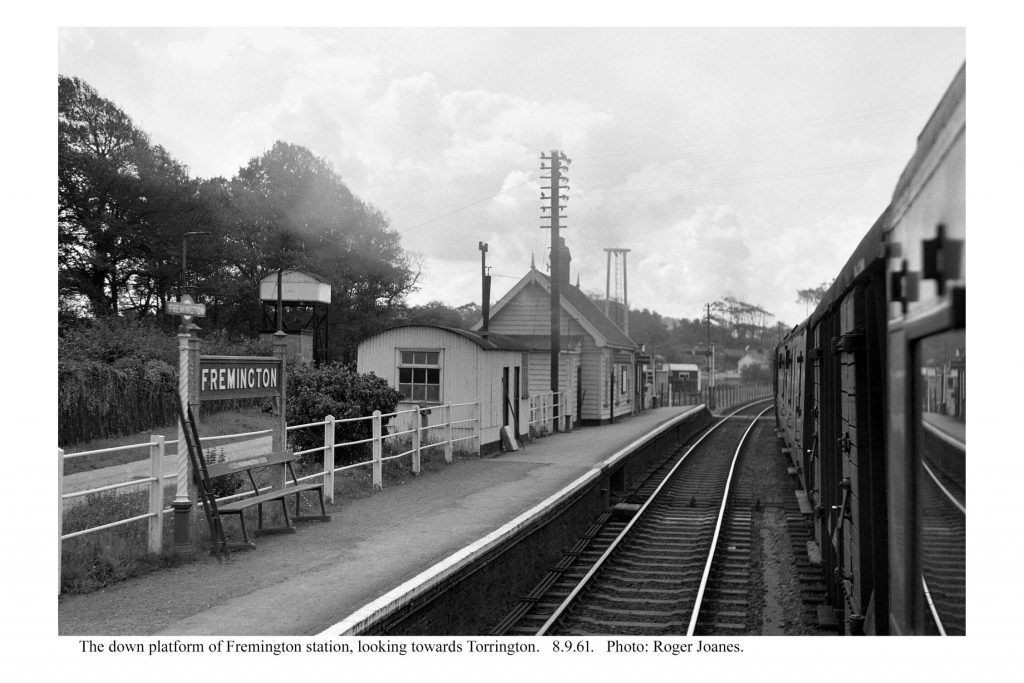

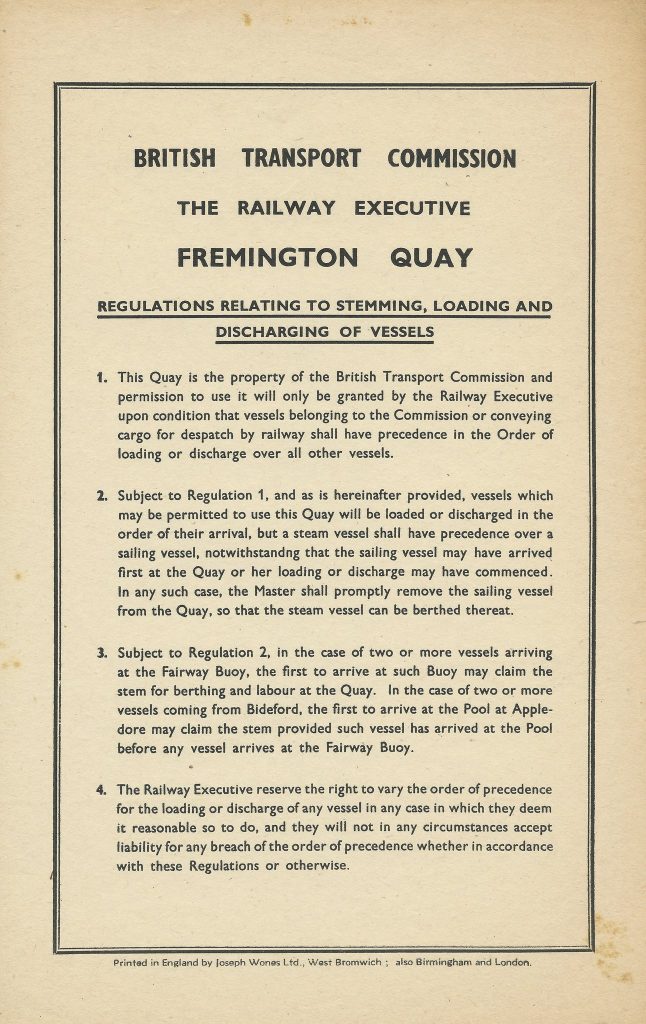

Fremington

Fremington was the busiest north coast port in tonnage terms west of Bristol. Much North Devon clay was exported from here and some cargoes were taken by coastwise shipping.

The scout had seen a lady and two children join the train with their bikes at Crediton, seen off by hubby. At Barnstaple, their cycles had to be unloaded first and so the scout stood back. Typically, impatient people were pushing to get on before the arriving passengers had detrained. The lady had difficulty getting the children’s bikes off and the scout stood in the door with hers so that she could take it from the platform.

Not for the first time, the scout wanted to shout: “It’s a terminal station. The driver is at the wrong end. Will you please let us get off?!” It is the same at intermediate stations: passengers milling around the doors have not the sense to see that if they stood back they would find it easier to board.

At Fremington, the scout caught up with the family. The lady thanked him for his help and the scout replied: “Aren’t people daft? Did you notice that the first three to board were gormless teenagers?” She seemed to bristle at this but then chuckled. She said that they were planning to ride the 25 miles to Meeth. “Isn’t that cruelty to children?” teased the scout. “Is it?” she addressed to the children. “NO!” came the united answer. They were only small and the scout was impressed, although saddened by the motor mileage that would be incurred by hubby driving to Meeth to collect them. She told the scout that she taught at what had been Exeter’s Steiner school and a discussion ensued about education, green travel plans and the stoppage.

The Teign Valley came up and the lady said that she had attended concerts at Sheldon. “Did you see the railway project?” was answered with, “Yes, we once had a look around.”

When the scout said that he was going to work through to Okehampton, the lady said that she would have liked to ride from there to Torrington to camp, but she dared not take the children on the busy road.

She was stopping to fortify the children at the cafe and wished the scout an enjoyable ride. Over his shoulder, as he went to take photographs, he called: “They’re going to need thousands of calories!”

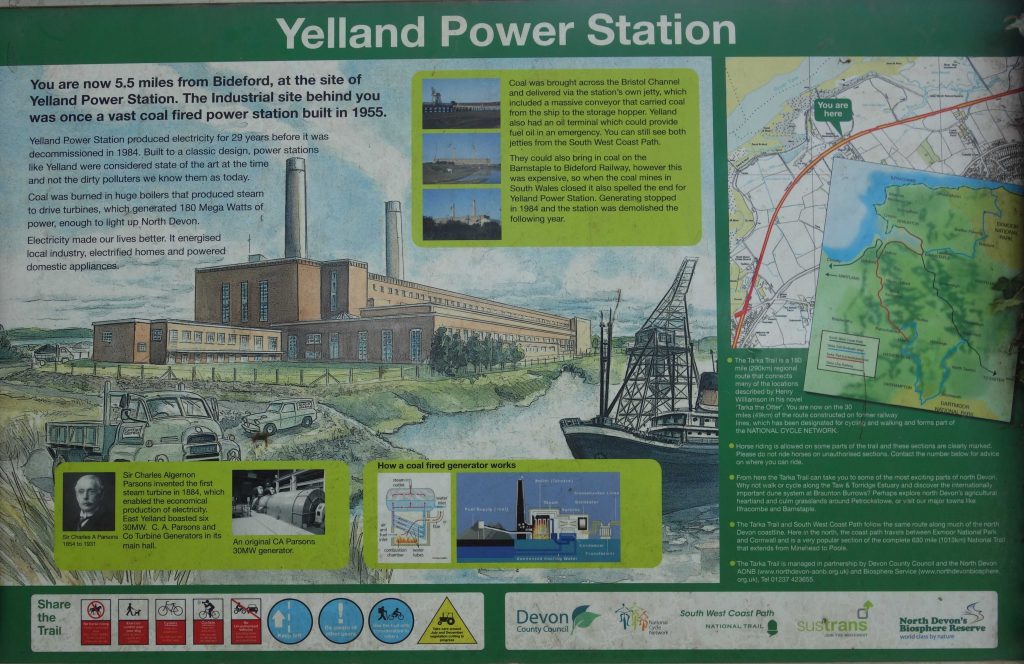

Yelland Power Station

When the scout came past here in 1982, the power station was still operational. Work was going on which the scout thought had involved removing the siding gateposts.

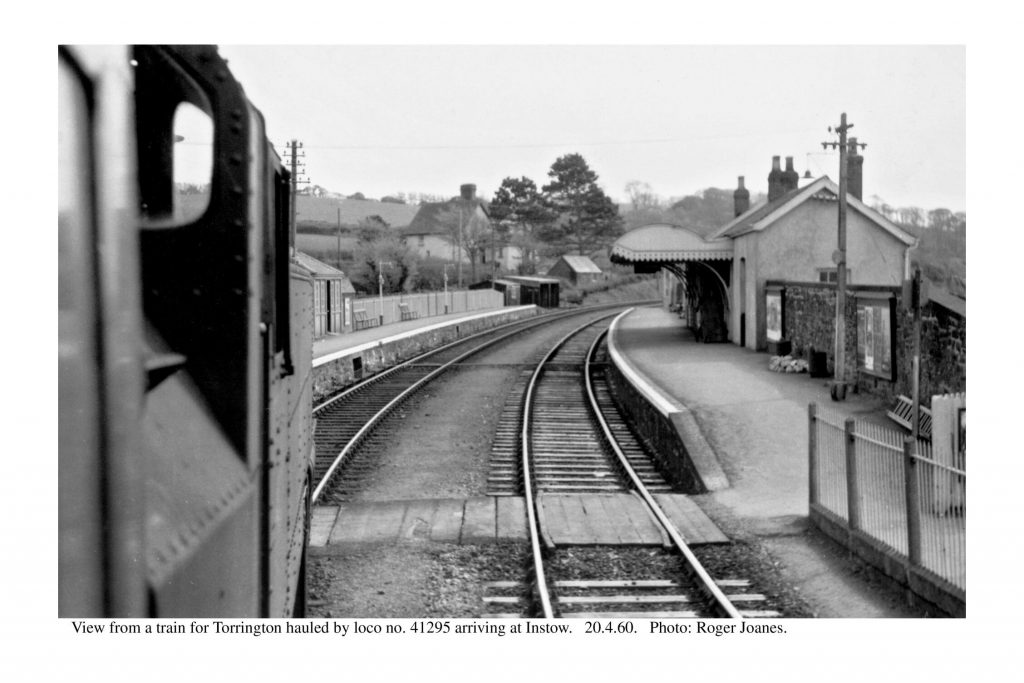

Instow

At the end of the Down platform, the scout spoke to a couple who earlier had kindly stepped back to allow a clear view of the crossing. The scout boasted that he had been through Instow on a locomotive. The chap told the scout that he had been with the county and had arranged the Manpower Services labour force which brought the trail into being. He asked what the chances were of the county’s engineer on the job being called Richard Beeching.

The campaign to reconnect Bideford to the national railway network has been revived almost single-handedly by an energetic North Devon councillor, who has engaged a consultant to report on the economic case and study possible routes, it being accepted that this trail is untouchable.

The scout is firmly of the view that the trail has practically no value in transport terms and that its amenity value for the most part could be provided by the thousand and more miles of quiet lanes with which Devon is blessed.

The estuarine views which the trail affords could still be enjoyed from trains, although the scout suspects that most passengers would continue to stare at their telescreens, as they do while passing along the sea wall in South Devon.

These trails are far from being environmentally benign. A huge number of car journeys is generated by people often travelling long distances to do a very small mileage on what are seen as cycling reservations—the only safe places to cycle.

And at every access point, dog owners’ cars sit while the drivers use the trails as linear parks and walk the mile or so with their mutts that they could have done from home, or on green spaces much nearer home.

When it is said that the best thing for cycling would be more cyclists, the campaigning organizations surely do not mean that cyclists should hide away on reservations: they mean that mechanized pedestrians should take up their rightful place on the roads, where their numbers would tend to quieten traffic and maybe encourage drivers to saddle up themselves.

It should have been made clear when abandoned formations were adopted for leisure use that it might only be temporary and that railway reinstatement would have to be allowed.

Bideford

What is left of the station is cared for by the good folk of the Bideford Railway Heritage Centre, who serve refreshments in a carriage at the platform.

The North Devon Railway Report (subtitled: The findings of the North Devon Railway Enquiry), published by David & Charles in 1963, recommended that:

“Ordinary goods traffic should be retained at Bideford and Torrington, and a skeleton service for long-distance travellers run as far as Bideford.”

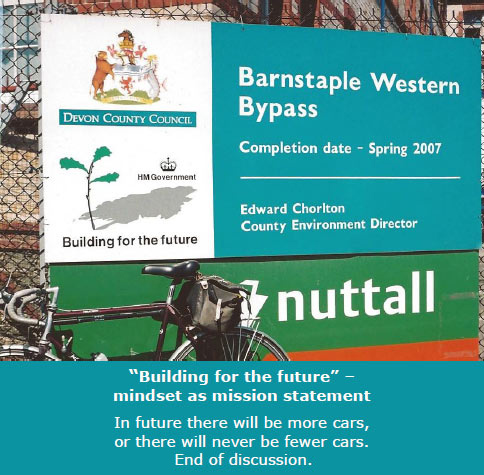

Like many of the reports published in the 1960s, it seemed as if the writers were only thinking of public transport, certainly in rural areas, providing for a transitional period, and that in the end everyone would own a car and all goods would be on the roads.

The sailing ship, Kathleen & May, which the scout had seen in Gloucester in July, was moored here during its stay in Bideford.

The North Devon line can be followed most of the way to Instow. Beside the line to Torrington, going off picture at the bottom, is the private siding of Bartlett, Bayliss & Co., timber merchants, whose large stockyard can be seen. The siding was later shared by Shell-Mex & B.P. and South Western Gas Board.

Oddly, there is only a few small vessels alongside Bideford Quay. Ships are seen moored off Tapeley Park at top right, possibly laid up because of the slump. The scout recalls seeing the same on the Fal after the 2008 crash.

The confluence of the Taw and Torridge, and Braunton Burrows, are at the top of the picture.

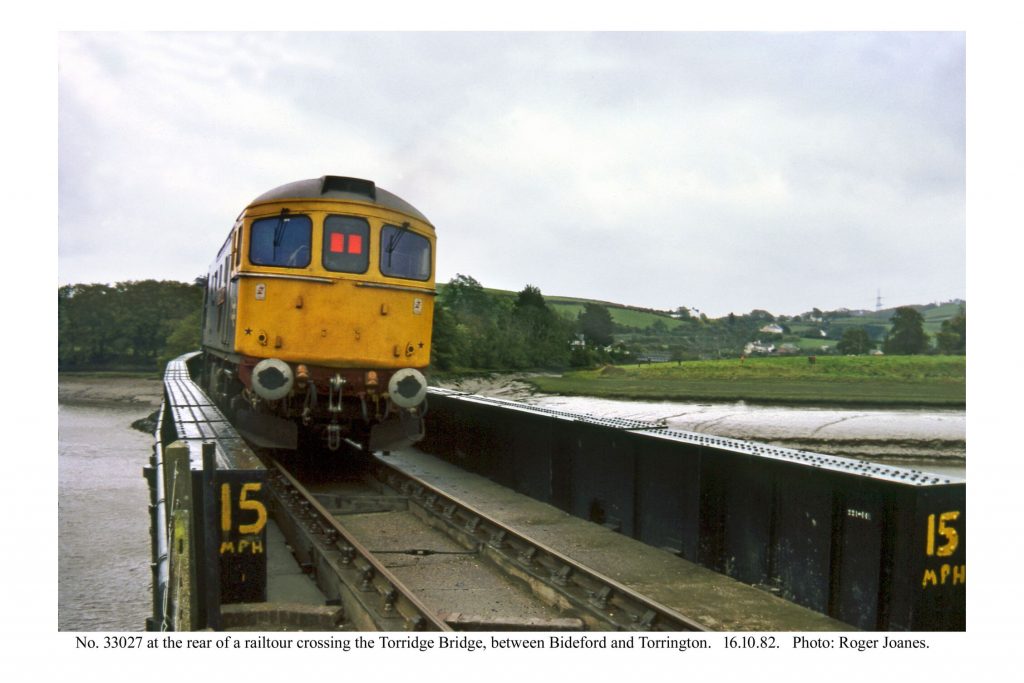

Going back many more years, the scout remembered the driver blowing the horn to alert a fisherman sitting on a midstream girder of Landcross Viaduct, who looked up in disbelief; word had already gone around that the line had closed. It was only when the engine ran onto the viaduct that the fisherman thought it best to retrieve his tackle from the four-foot.

The P.W. Chargeman kept repeating: “Fifteen mile an hour, Drive.”

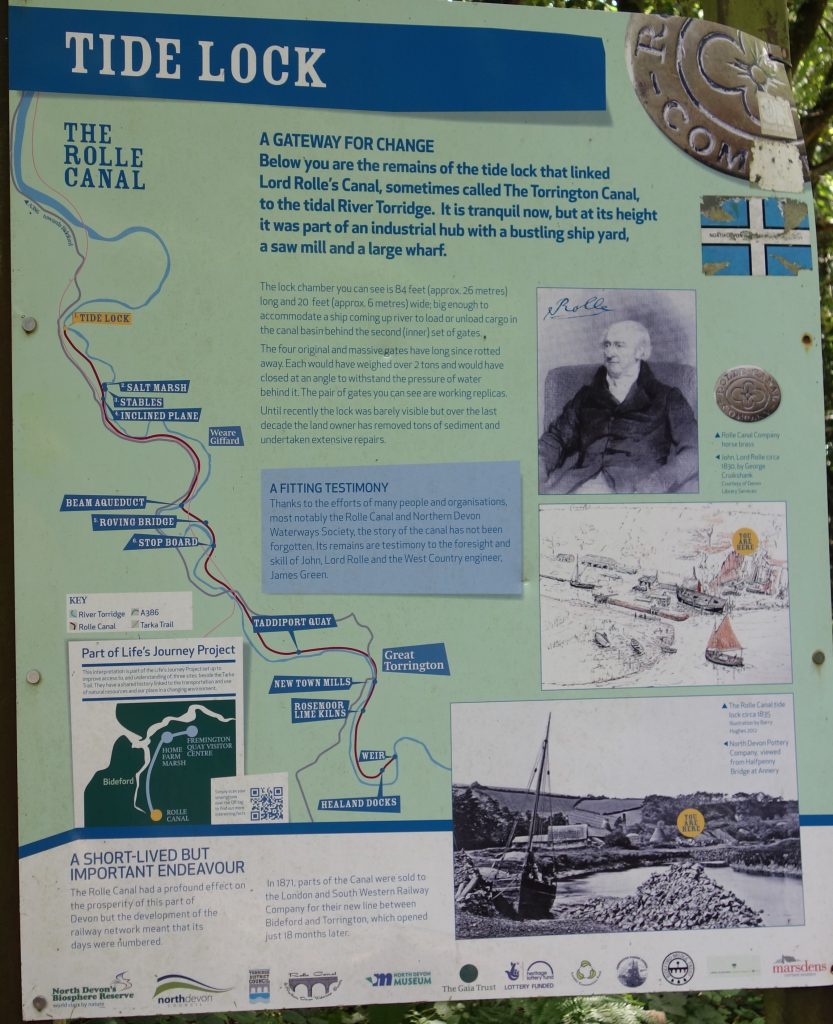

When the scout turned from viewing the lock, a corpulent fellow sitting on a bench called out, advising that more relics of the canal could be found further along. The scout thanked this local guide and seeing that he was enjoying a smoke after a spin on his electric bike, said that he had earnt a fag. He held up a cigar and the scout ruined his scrounging pitch by saying that the costly ten he had recently bought would have to be the last. The chat which followed led to agreement on the real plague, that of obesity, and the scout left him with the thought that a huge burden had been placed on the health service by so many people no longer dying prematurely of smoking-related diseases.

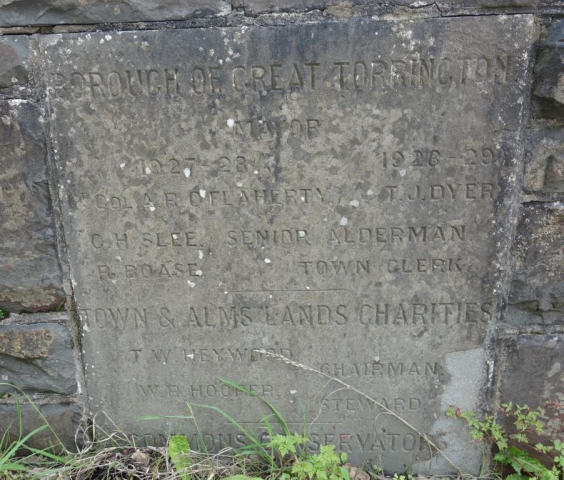

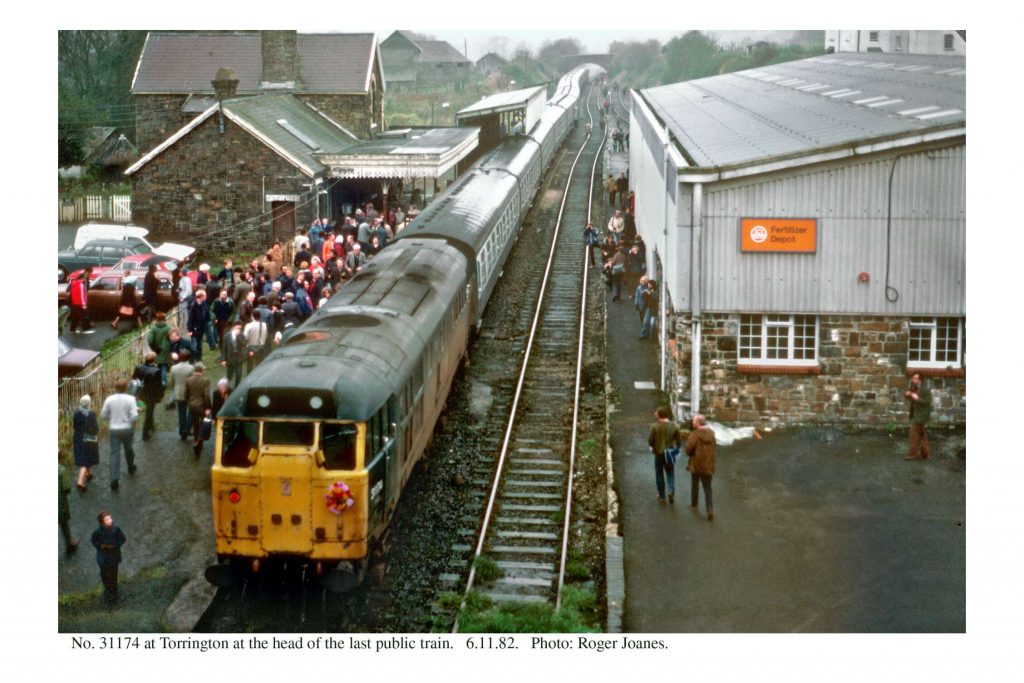

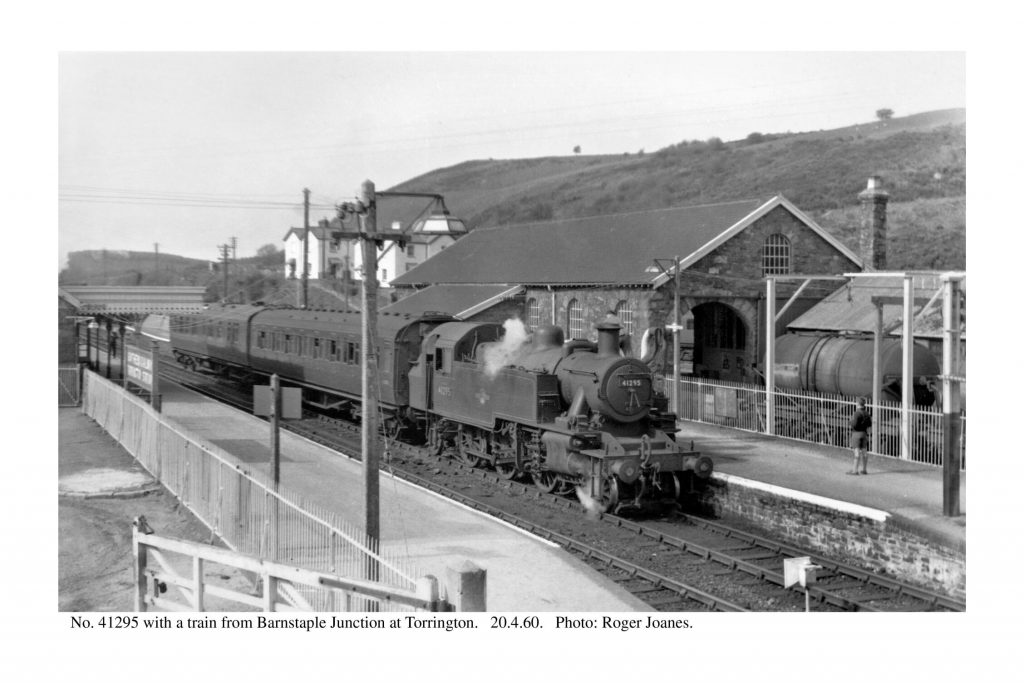

Torrington

The station, always Torrington rather than Great Torrington, is home to the Tarka Valley Railway, a kind of day centre for decaying crocks (quite unlike Christow). The two-car unit was a virtual gift from train operator, First.

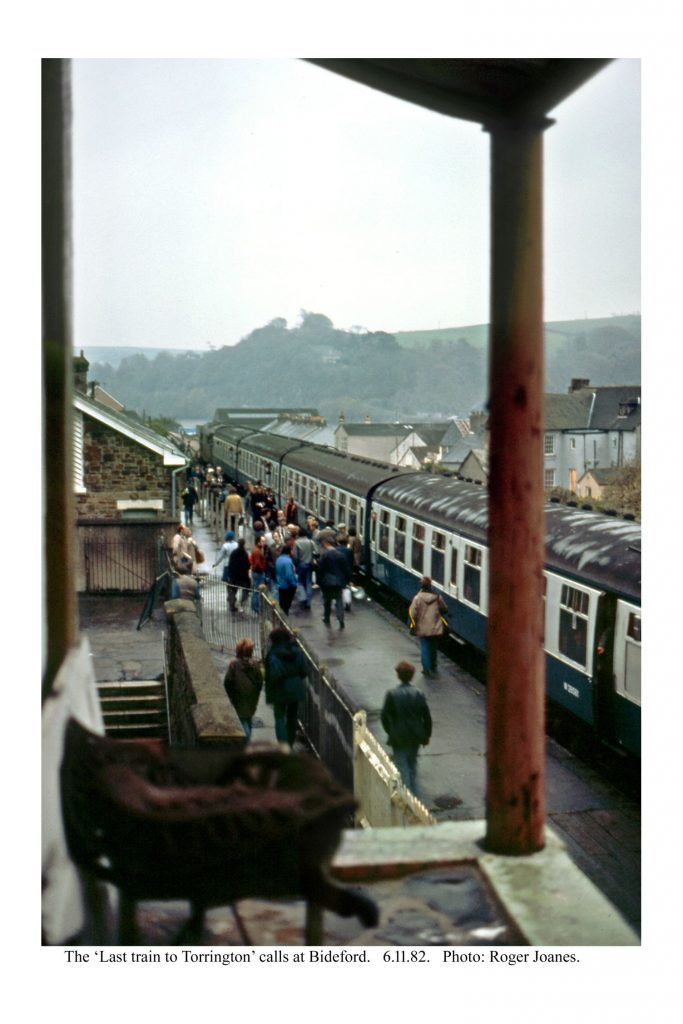

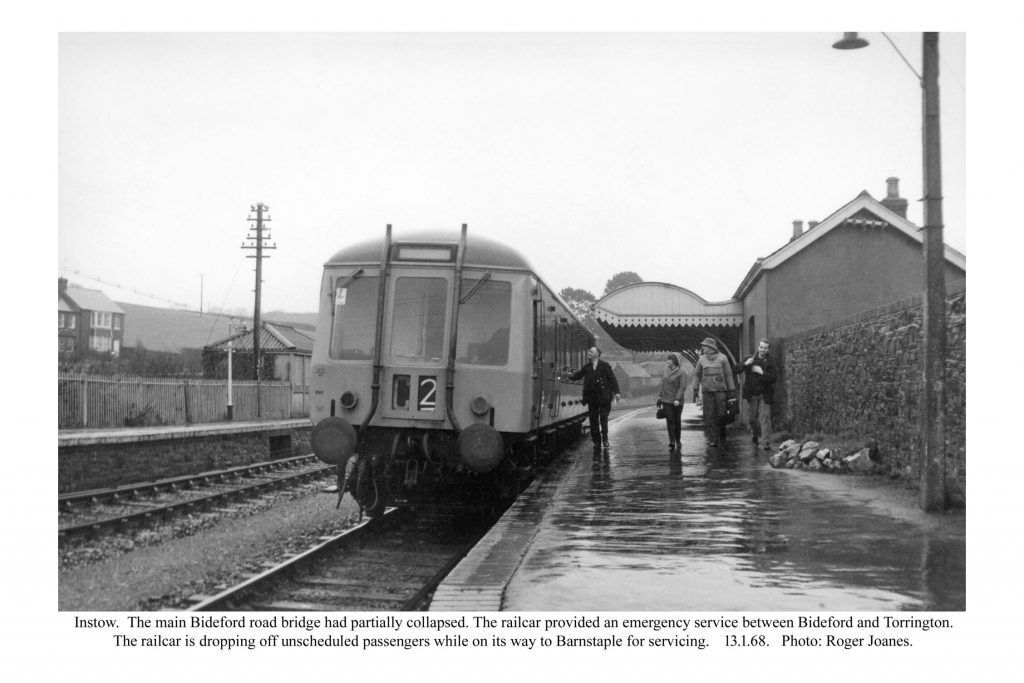

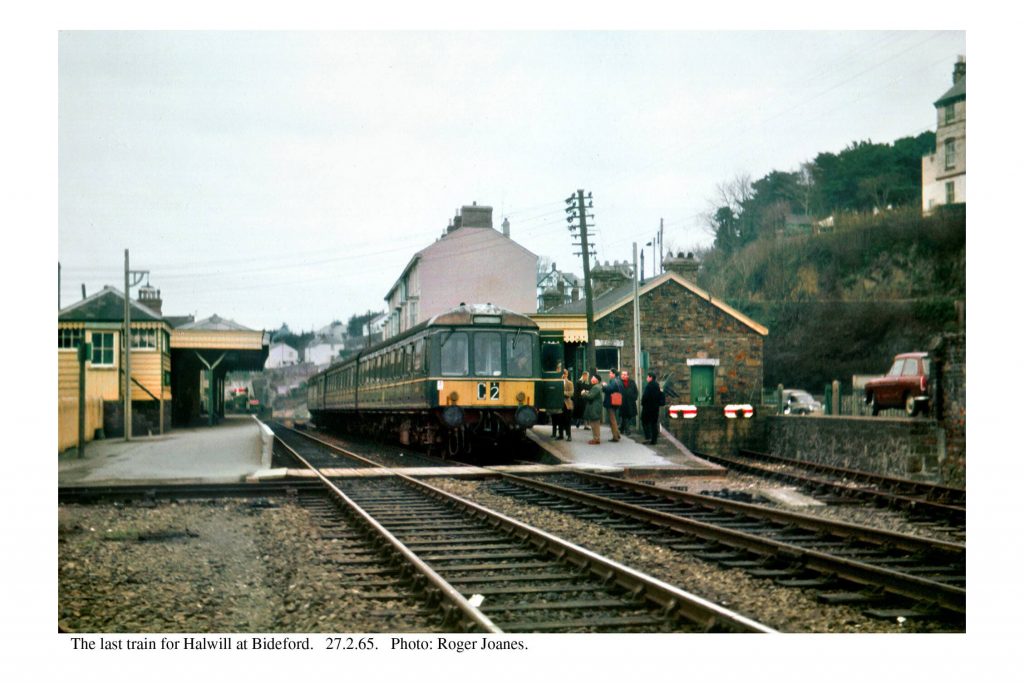

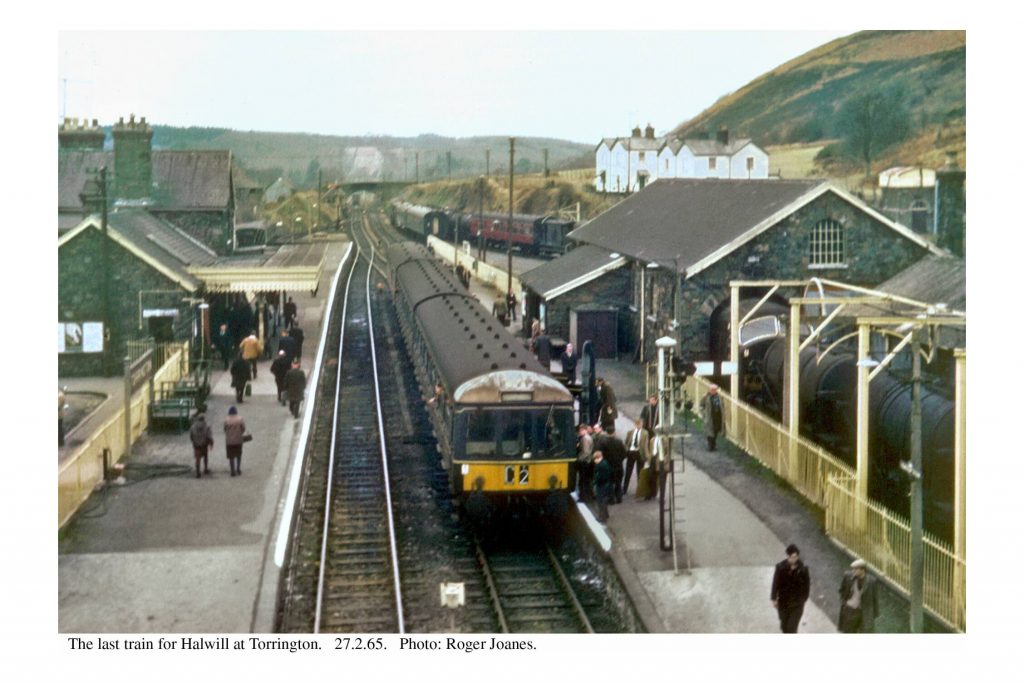

The passenger train service was withdrawn between Barnstaple and Torrington in October, 1965. There was a brief special resumption in January, 1968, after a partial collapse of Bideford’s Long Bridge.

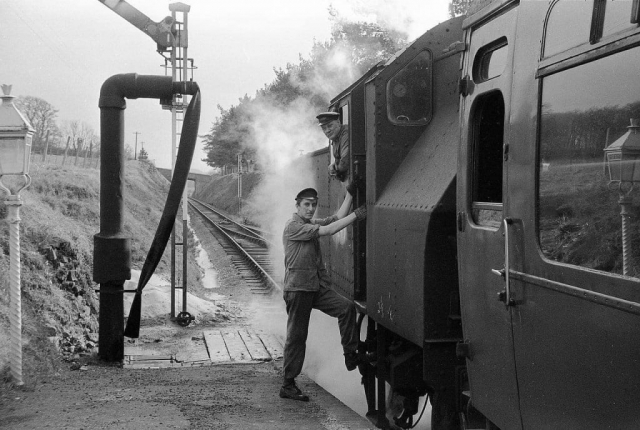

A new milk-loading facility was installed on the Up platform in 1976 but was only used for two years. In the scout’s early days with B.R., Torrington was one of four places that sent tanks for attachment at St. David’s to the London milk trains.

The scout did not want to sit with listless motorists stuffing their faces at the station and so, spurred by a friend pointing out to him how useful a place the town of Torrington is, he rode up the hill and got to the centre in 13 minutes.

A little way up the hill, the town’s sign proclaimed that it was the “healthiest place to live.” This was based on research by the University of Liverpool in 2019 which found that the small market town has low levels of pollution, good access to parks and green spaces, few retail outlets that may encourage poor health-related behaviours and good access to health services.

Sandford’s should have had the scout’s custom, but routinely he went to the Co-op and chose the large “meal deal” at £5 for cardholders, which to took to the edge of the cliff not far away and settled on a bench with these fine views.

It took the scout five minutes to get back to the station, where he resumed his exploration.

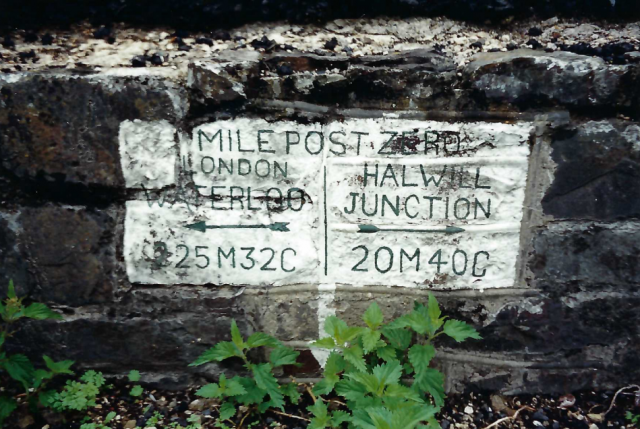

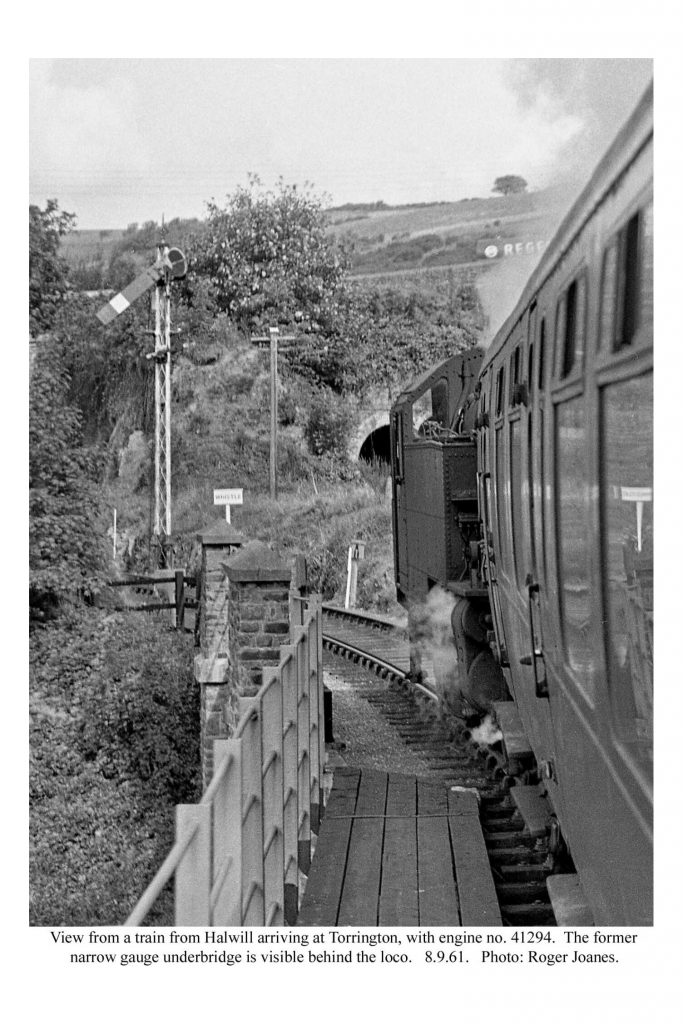

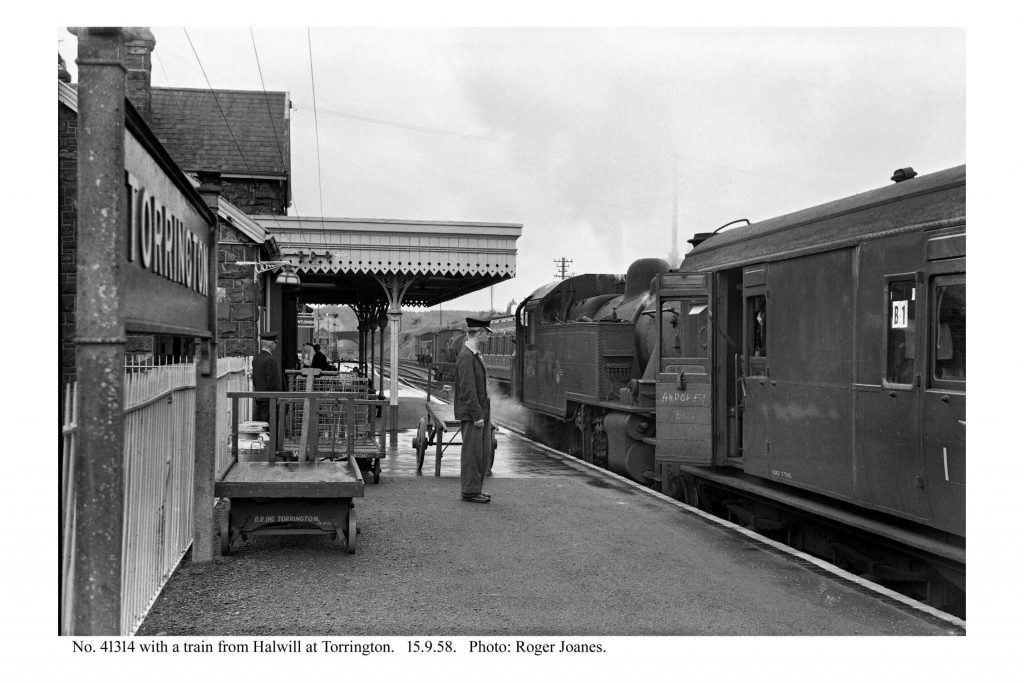

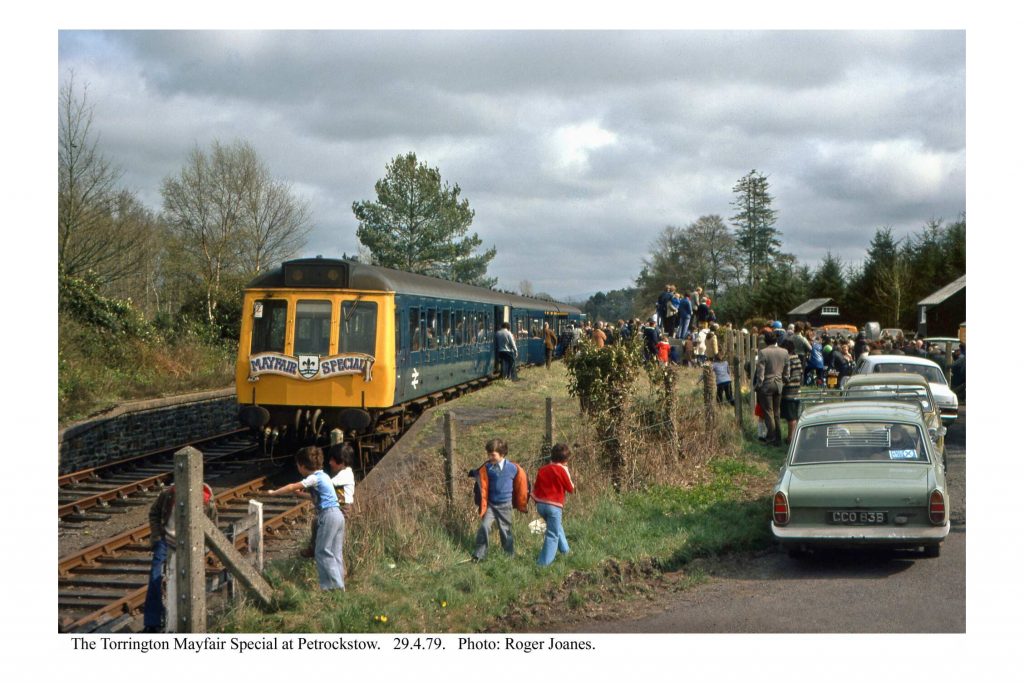

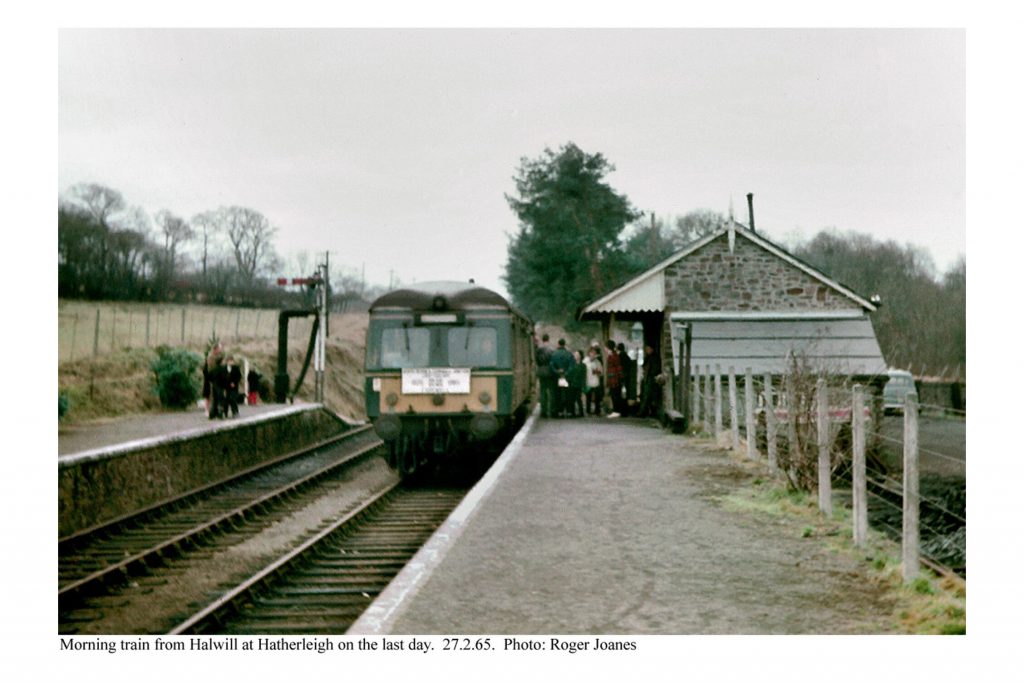

The North Devon & Cornwall Junction Railway, the last to be opened in Devon, lost its passenger service in March, 1965.

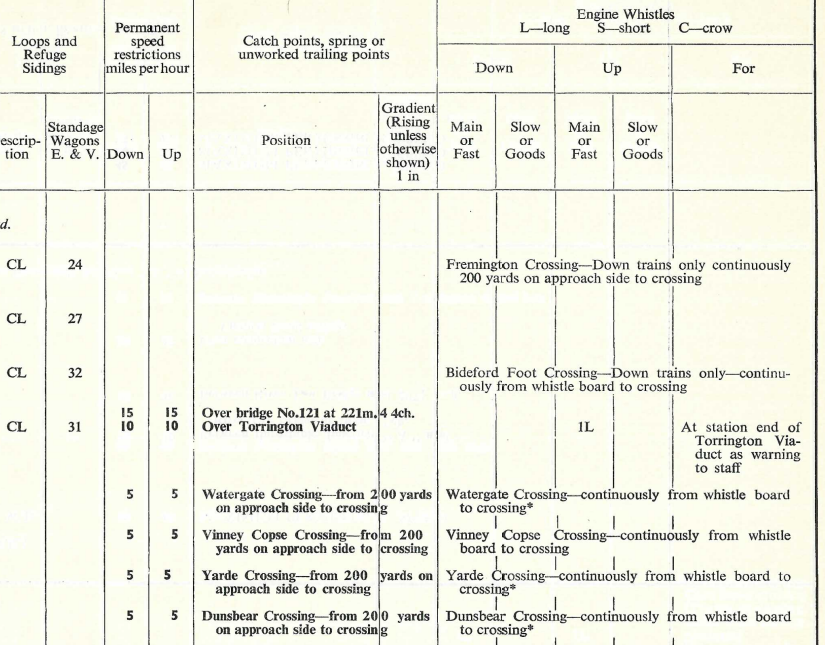

The scout was careful to observe the 20 m.p.h. P.S.R. up the gradient, which on the narrow gauge line was as severe as 1:35.

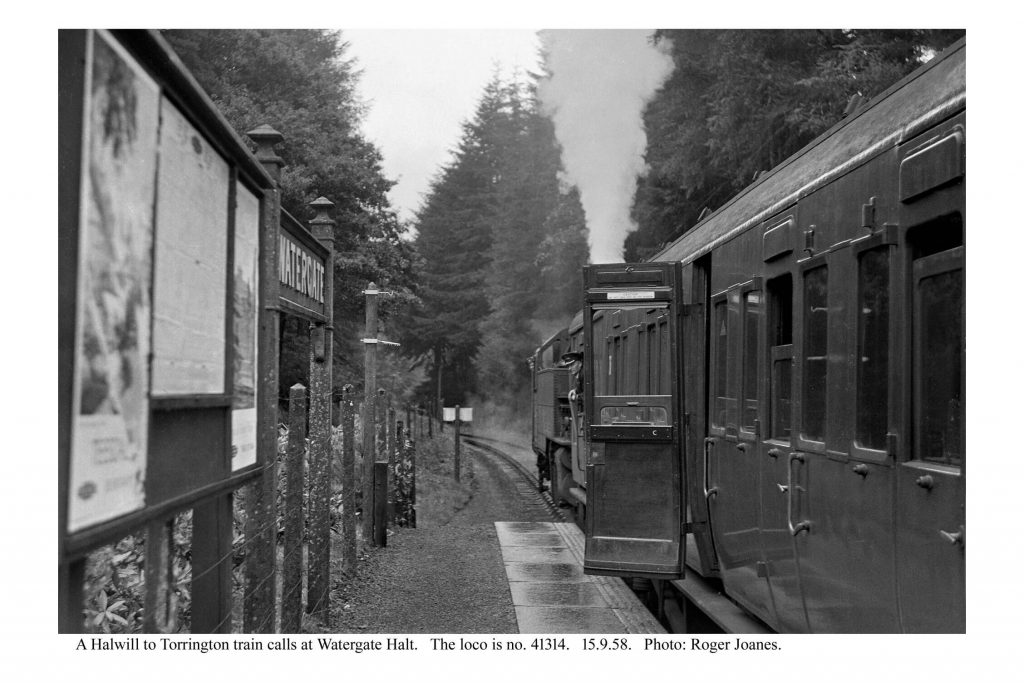

Watergate Halt

Here the scout bumped into a very friendly elderly pair riding electric bicycles. Her family had run the post office in Taddiport, which was busy when the Dairy Crest workers from the factory came to buy postal orders to go with their pools coupons. She remembered as a ten-year old going on the train to Bideford with her friends. Her son had worked at Sandford’s since he was a boy. Bakers start at 3 a.m. The chap’s son ran the transport business which still occupies part of the dairy site. One of his late relations remembered the narrow gauge line and he gestured to the siding that was provided here.

There was not a great deal of traffic on the B3227 which the line crossed here but the lady was still nervous about returning that way. Her electric machine had been bought secondhand for £1,200 from someone who had been seriously hurt after a fall and who had no memory of it.

Yarde Halt

Short sections of the gradient on either side of the summit here were 1:30 on the narrow gauge line.

The paths lack the interest, stimulation and challenge of roads, with their ups and downs and constantly changing scenery. And the paths often do not lead past settlements, or these lie hidden from the paths: in the 25 miles between Barnstaple and Meeth, the only village that the path has any direct connection with is Instow. Even though Long Bridge is but a short way from Bideford Station, the scout wonders how many venture across to the town and how many just pass through or settle at a nearby table for some grog and grub.

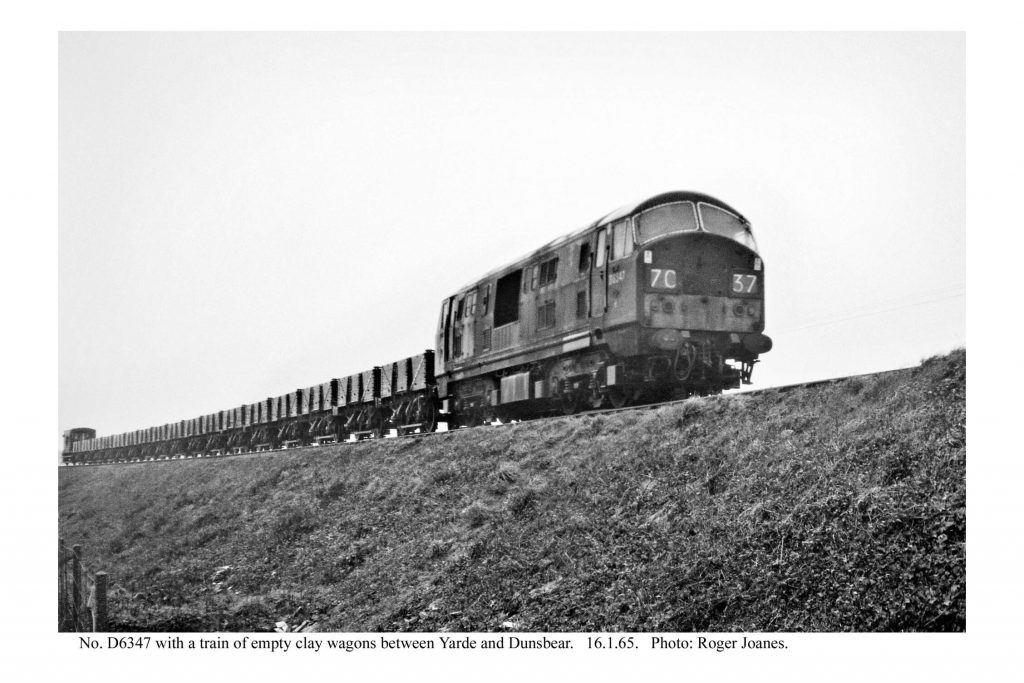

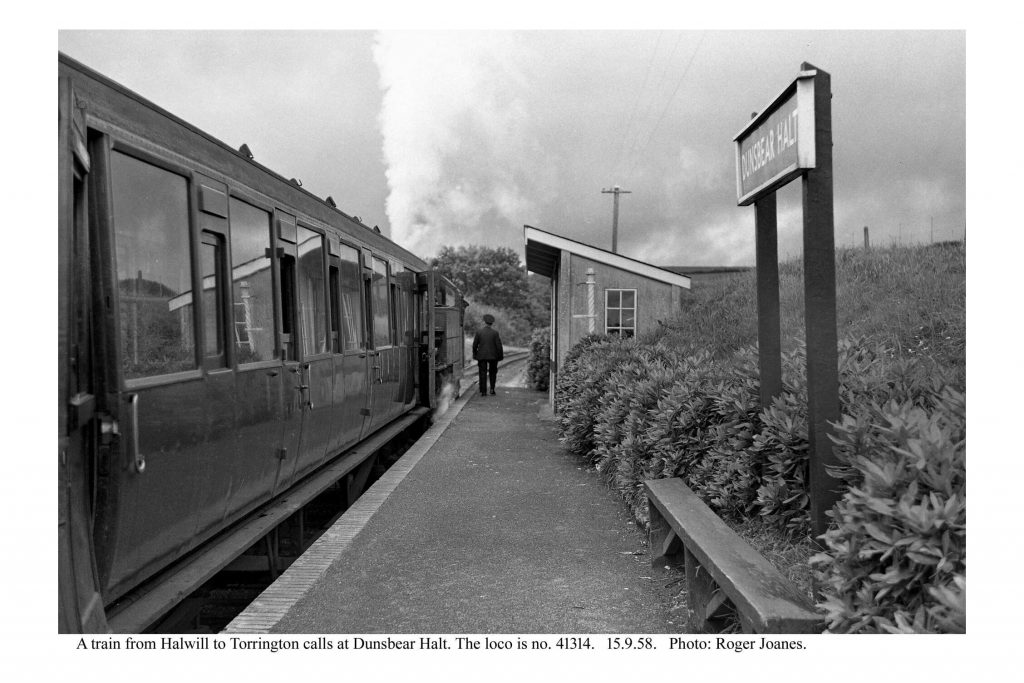

Dunsbear Halt

Taking advantage of the increase of line speed from Dunsbear, the scout sped off at 25 m.p.h., missing the former standard gauge connection with the works. He backtracked to the place where he had got down from the loco and watched it enter the works.

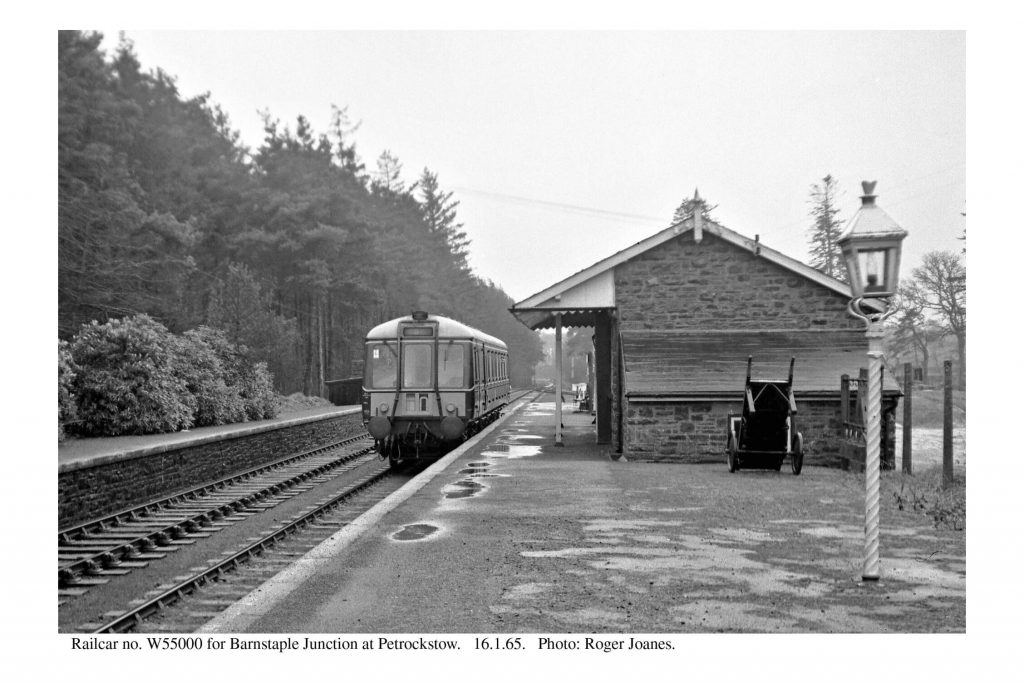

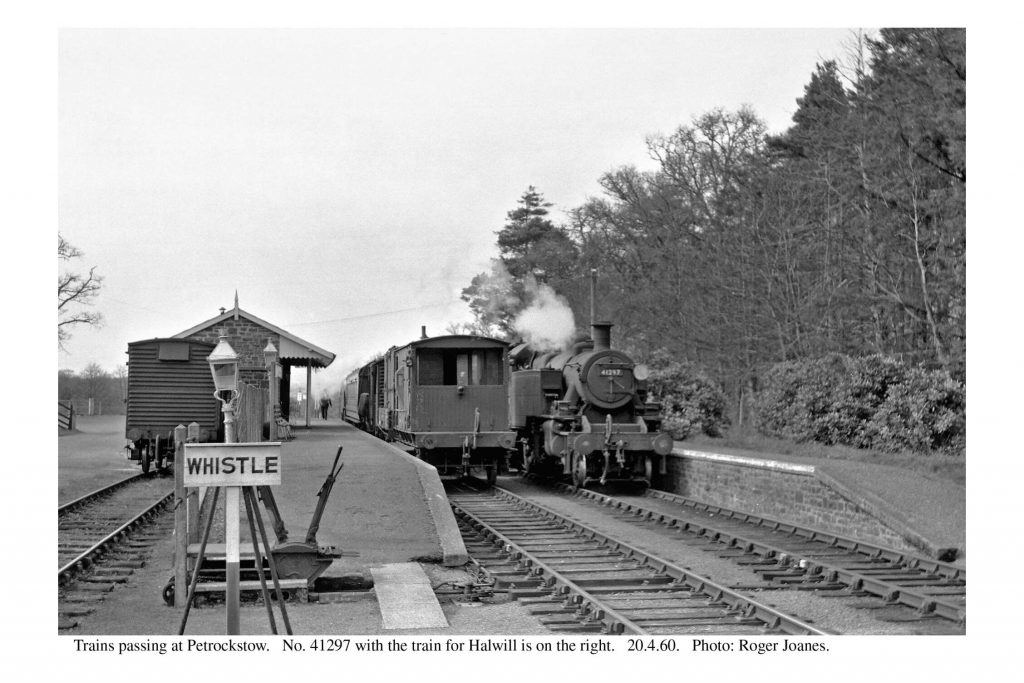

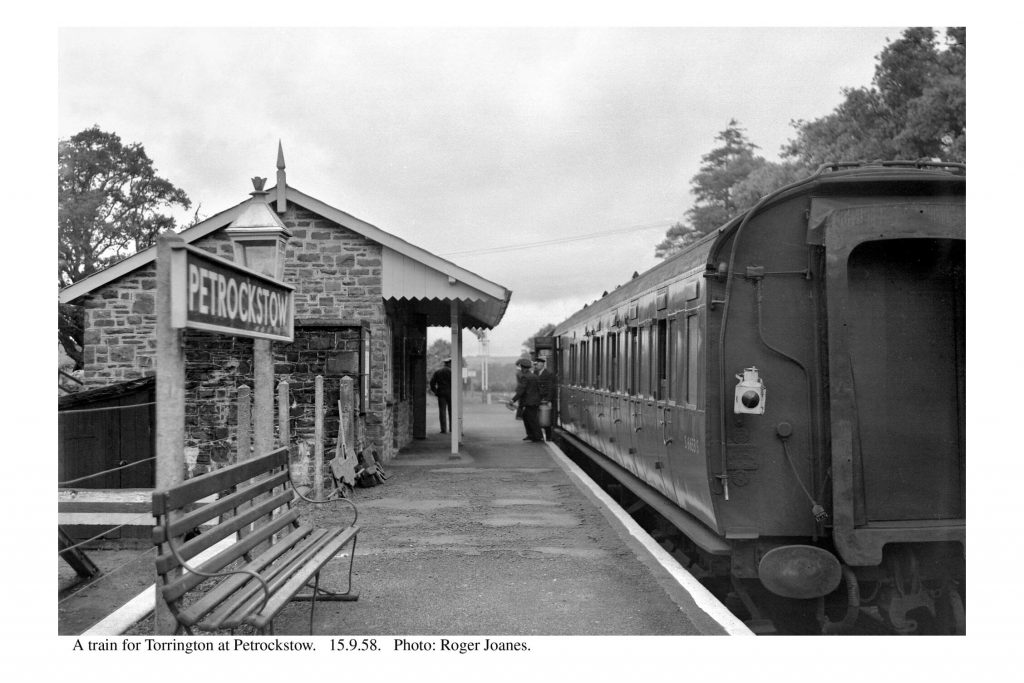

Petrockstow

The station, about a mile from the centre of the village (Petrockstowe), was a staffed crossing place.

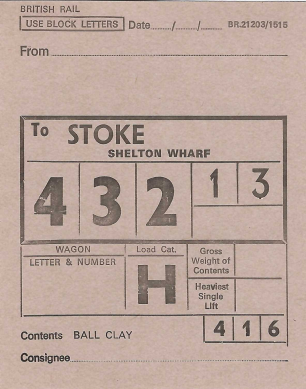

The clay works at Meeth lay between here and Meeth Halt. The scout’s excursion went on as far as the loading dock and picked up the empty wagons. The air-braked hopper wagons which would continue to carry some of the clay from South Devon were too heavy for this line. Grant aid for new loading facilities would have been available.

On the return journey, the young scout asked the driver, a tough old Southern man brought up in Exeter’s West Quarter, whether he was sad that this would be his last run on the line. “Quicker us gets back to Barnstaple, the better,” was his unsentimental reply. A man who had seen so much of the railway’s decline and dismemberment had become inured to it. The scout has begun that same hardening process.

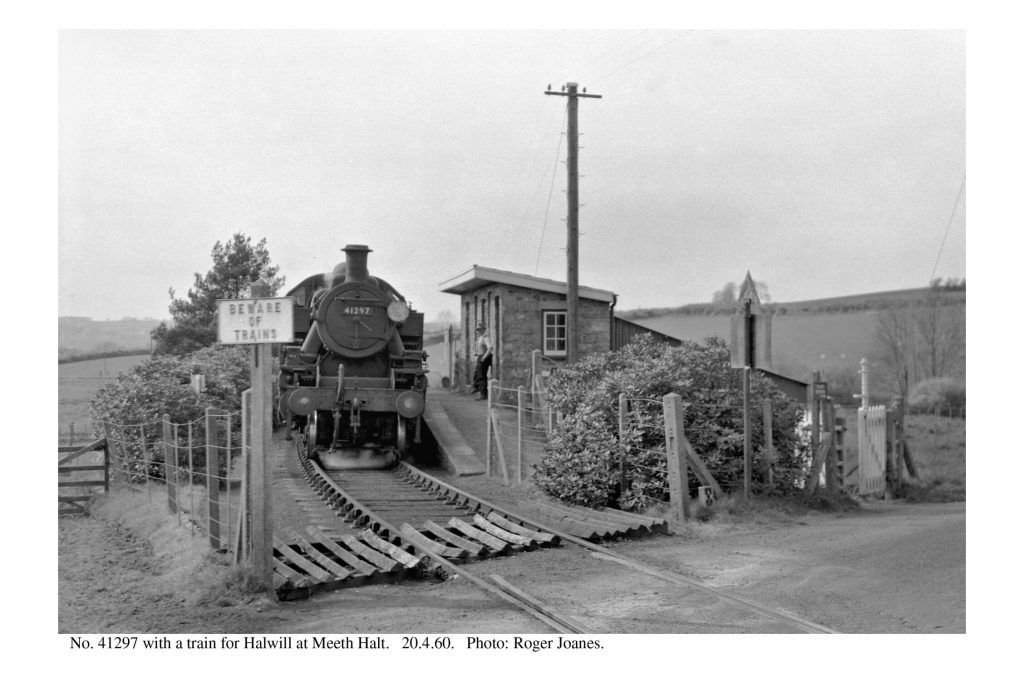

Meeth Halt

The scout then headed towards Hatherleigh along the A386. He is never lulled by the experience of safe paths like the Tarka Trail, but he wondered whether there was a danger that some cyclists emerging onto a road with fast moving traffic may not fully have their wits about them after the relaxation.

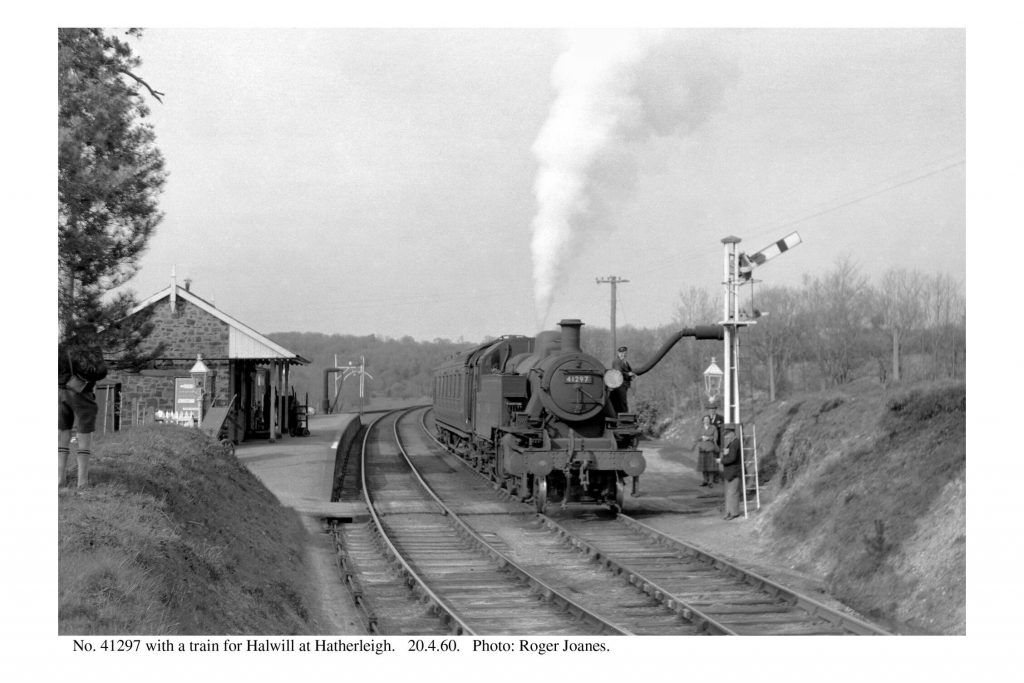

Hatherleigh

The station, about a mile from the town, was a staffed passing place with sidings, a cattle pen and another agricultural depot.

Earlier ideas had a railway heading for Sampford Courtenay or Okehampton, but Col. Stephens chose Halwill and so the line veered west after leaving Hatherleigh. This meant that passengers had a 20-mile rail journey to Okehampton which would have been not much more than seven by road.

Earlier in the day, the scout had vaguely thought about continuing to follow the line to the end, but at this stage he decided to save Hatherleigh to Halwill for a circular ride from Okehampton.

As he sped downhill through Hatherleigh, he thought of the disturbance caused 100 years before when troublemakers drafted from the Plymouth unemployed to work on the construction of the light railway got drunk and set upon a police sergeant who had ordered them to return to camp. The scout continued along the road which the lady from Crediton, quite understandably, would not ride with her children and was in plenty of time for the 1830 departure from Okehampton. Not one cyclist was seen between Meeth and Okehampton.

When the scout returned to the utilicon, he had ridden 52 miles.