Although his intention was to follow the Budleigh Branch from Tipton, the scout had been intrigued by the Feniton churchwarden’s enthusiasm and so decided to return to the village to see inside the church.

The line between Exeter and Axminster was closed for engineering work and so the scout had to ride the 15 miles to Sidmouth Junction, which, beyond Dog Village, was, as usual, most pleasant.

It is baffling to the scout that the ever-swelling population within easy reach of the gently-graded byways that radiate east of Exeter does not disturb their quiet.

Even mid-morning, the sun was still chasing off the mist that lay heavy in the hollows, a reminder that the start of autumn was only a few days hence.

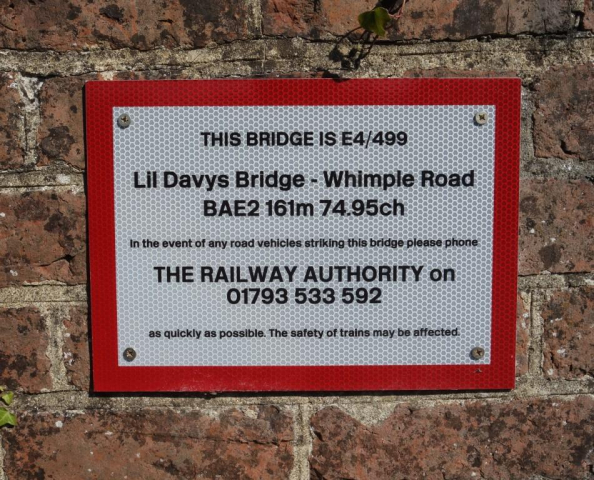

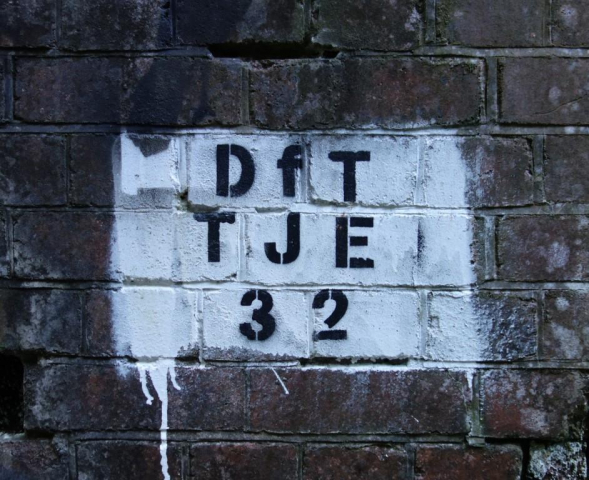

The scout did stop at the next bridge, whose nameplate he could not see.

Seconds after passing New Town in 1947, the “Belle” would have burst out from beneath this one, along the Up, the line which is gone.

Most days, now, all that will be seen are diesel units. For one who has eaten a cooked breakfast at a white-clothed table while watching the East Devon countryside flash past, it is all a huge and depressing comedown.

Despite the several stops, the scout rolled in at Sidmouth Junction only 38 minutes behind the train that he would have caught, had the service not been disrupted.

There were no pamphlets in the “Church History” dispenser so the scout went to the churchwarden’s house. David Lanning, actually the retired churchwarden, whose three-volume detailed history of the church lay on a chest, was in his garden again and was only too pleased to accompany the scout back to the church to discuss its features, most notably the “transi” tomb.

It is thought that these sculptures may have been carved using wretched sufferers of syphilis as models. More on this – actually, one of 47 that remain – can be found in the brief church history.

The scout pointed out the worm passages in the rood screen which must have been there when the wood was carved. Mr. Lanning said that he had never noticed this detail, one that may be drawn to the attention of his next visitors.

The only stop the scout made in Tipton was outside the primary school, where a teacher was seeing his class safely across the road. As he rode on, the scout heard the teacher scolding some children who must have been cheeky. The scout went back and said to the man, by now locking the gate, that he didn’t think teachers were allowed to get cross with children. “I don’t give a monkey’s,” he replied, adding, “I’ve only got a year to go.” And after the scout, over his shoulder as he started away, congratulated teach, he finished with: “Little perishers!”

The scout climbed Hayne Hill out of the village, as he had done at the beginning of the month, but this time crossed the former Sidmouth Branch and continued along the eastern side of the valley to Harpford.

Between Tipton and Harpford, the scout did not see anyone. Confined to an Otter Valley “trail,” people would seldom see this little corner by St. Nicholas’s Church in Harpford.

The scout had come from the right and went left to join the busy 3052 for the short ride to Newton Poppleford.

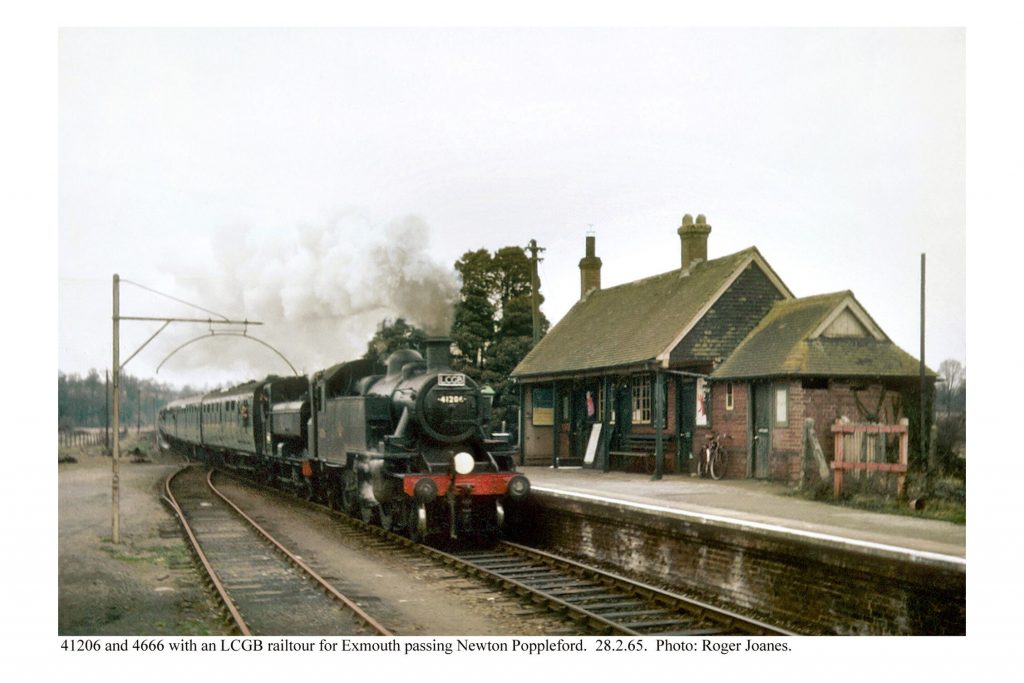

Newton Poppleford

Two footpaths cross the line between Newton Poppleford and East Budleigh. The scout decided that the best way to include these was to take the lane from Harpford along the east side of the valley, cross to the west side and return to the east from Colaton Raleigh. This way he would avoid the main road past Bicton and make his approach to East Budleigh through the lovely, but car-strewn, Otterton.

East Budleigh

On the approach to Budleigh Salterton, a new length of the B3178 cuts through the railway’s embankment at Kersbrook. Peering into the foliage reveals the old earthworks on each side.

The scout rode along Leas Road to Greenway Lane and then turned into Clarence Road, the first of four streets of terraced houses built at right angles to the railway. He was sure that he had seen a photo of an entrance to the Up platform of what began as Salterton Station.

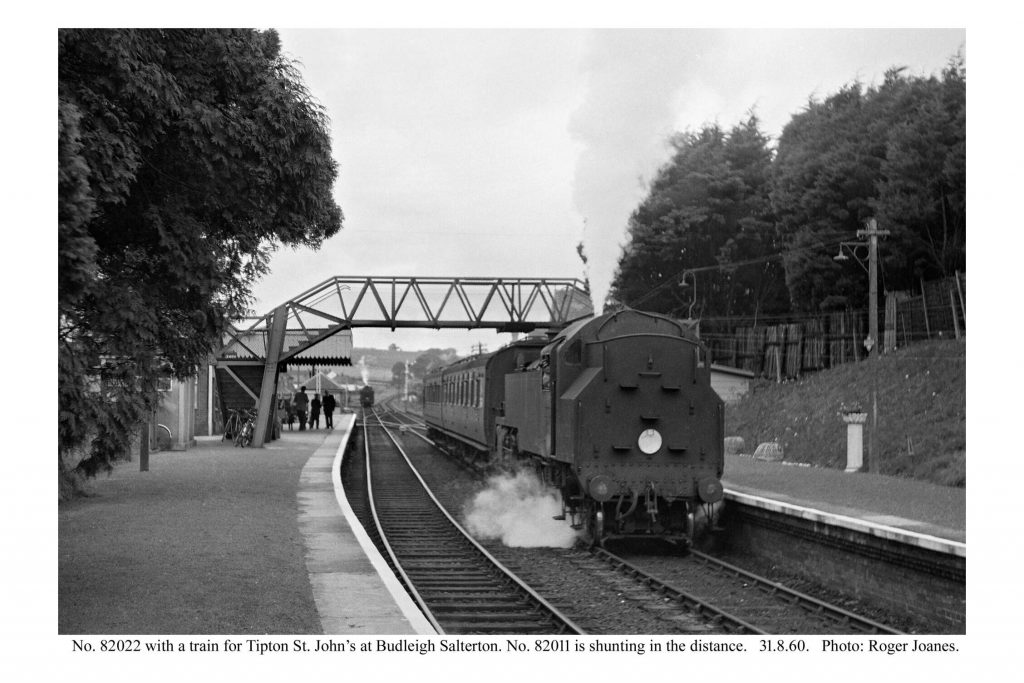

Budleigh Salterton

The duty manager at the sheltered housing complex had received a report from an elderly resident that a strange man was taking photographs of her bedroom window, so a young assistant had been sent to ask what he was doing.

She quickly succumbed to the scout’s charm and her glum face lit up with a smile. The scout despaired that he was now being accused of staring at old souls, as well as children. He recounted the occasion in summer when a Y.H.A. chap had asked him what he was doing, riding nonchalantly past the hostel occupying the former goods shed at Okehampton. “Only we’ve got a party of schoolchildren in,” he had said.

“And you think I may be a paedophile,” spluttered the scout. “Well, don’t worry. I had a child for breakfast.”

“That’s my sense of humour,” chuckled the young lady. The scout told her she had looked very serious as she had come along the pavement. She said that she was quite shy and hadn’t wanted to go out. Anyway, it was laughed off; it wasn’t the first time the old thing had told a story; and it wasn’t the first time someone had been seen photographing the site of the station.

A gaggle of schoolchildren came from behind and the frustrated scout said, “That’s it: I’m putting my camera away.”

The now friendly assistant told the scout that Budleigh was changing, with more families moving in and youngsters becoming more boisterous. When she had been at school, because everyone seemed to know one another, her every move was seen. “Was it the same when you started dating?” the scout enquired.

“Yes! I’ve been with the same boy since I was fourteen,” she replied. “To defeat the gossips?” quipped the scout.

He suggested that she was fortunate being in Budleigh and she agreed, seeming to be very fond of the place. She’d only once been to London and had been terrified by the seething mass.

Her shyness overcome, she chatted with the scout for twenty minutes about transport, housing and people. She agreed that it was unfair that Norman’s was remembered, but not the railway. Her mother had worked at the store which took over the goods yard.

Having to resume her work, she parted with, “It’s been lovely meeting you.”

The scout then got his last shot and belted down Station Road to visit the little Co-op.

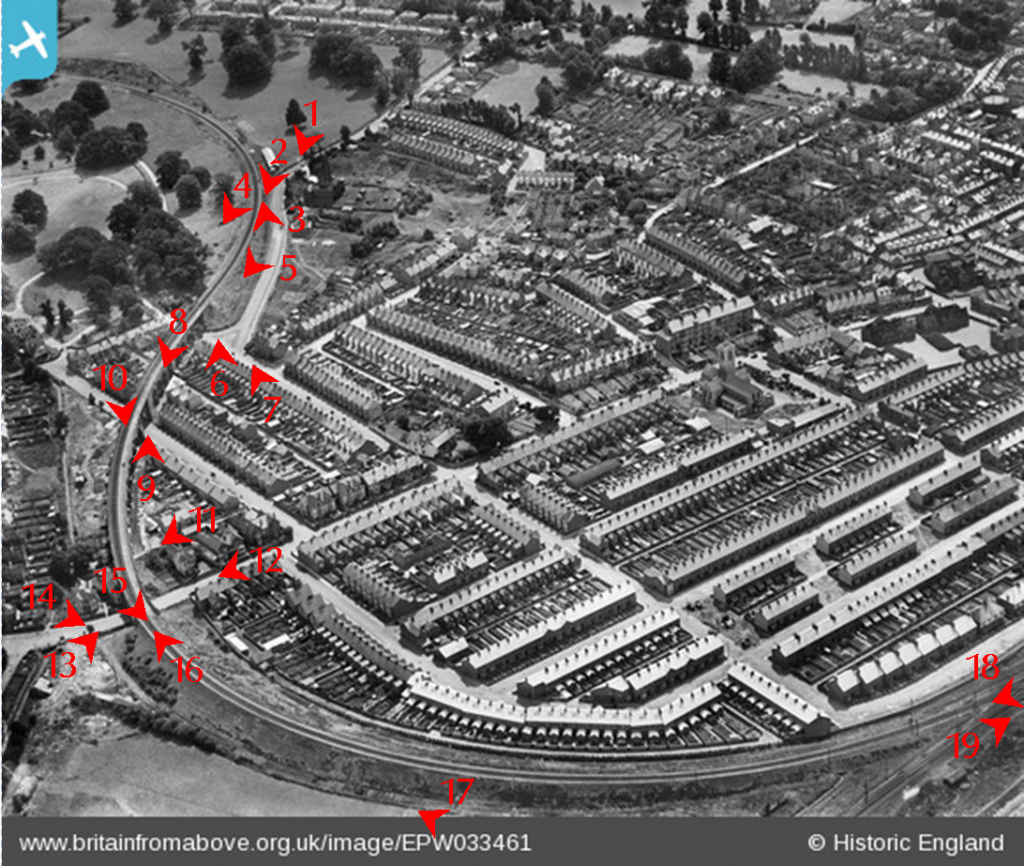

Station Road is at centre left, joining Stoneborough Lane at bottom right. Off Greenway Lane at top right, the first street of terraced houses, Jocelyn Road, has been completed.

The scout thought when he stopped for lunch at four o’clock that he would not be able to finish his refresher, but doubted that he would were he to press on, so he settled on a bench at the front and enjoyed the sun and the genteel atmosphere.

The line continuing to Exmouth was built by the L. & S.W.R. and opened in 1903, a month before the Exeter Railway, linking Exeter to the Teign Valley.

At bottom left is the bridge over Barn Lane. Greenway Lane has obviously been diverted to a new junction.

Another row of terraced houses adjoining the station has been built on Boyne Road. Not every green space has been built upon today. There are three sports pitches and an attractive park, “The Green,” has been made next to Station Road. The fields next to Dartk Lane (lower right), seen beside the cemetery, are still farmed.

The line was picked up again where it once crossed the B3178.

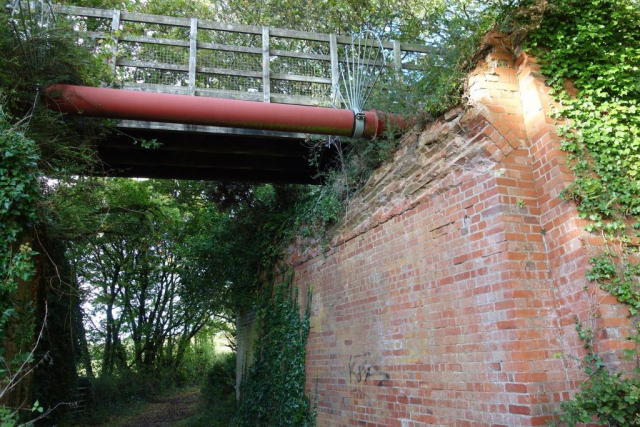

The scout crossed the road just uphill from the bridge and followed Bear’s Lane to the next overbridge, whence a path follows the lip of the cutting before joining the formation and continuing most of the way to Exmouth.

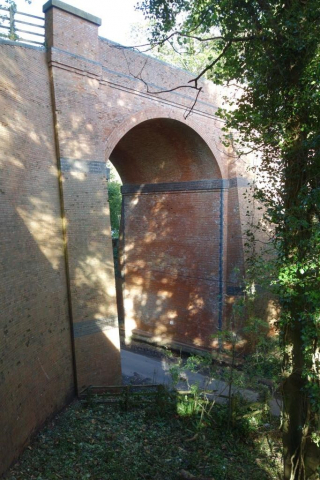

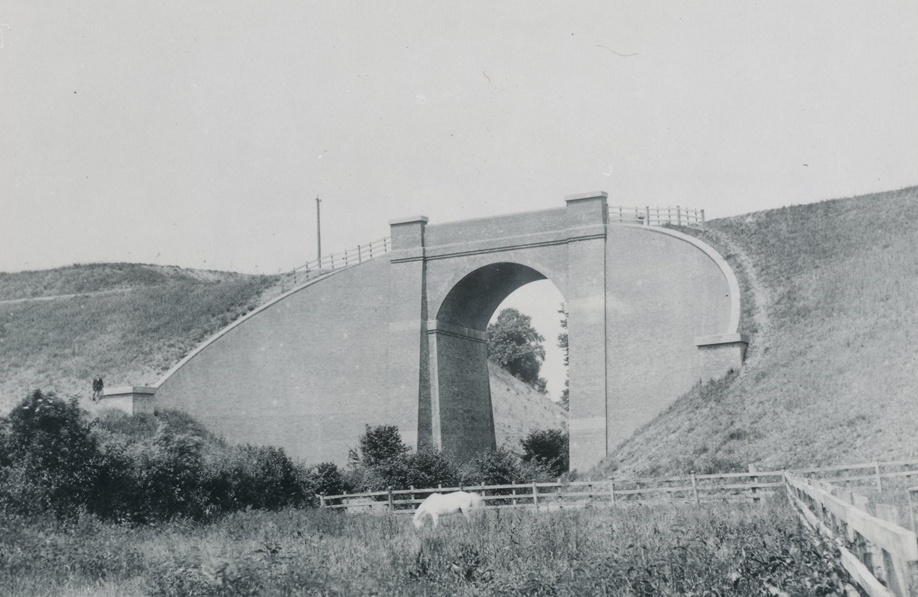

The scout wondered why this bridge had been built at a considerable angle to the line, when the lane could have been diverted to make a shorter arch, or a wider, skewed-arch bridge installed.

In early November, the scout went back for a closer look at this bridge. Fortunately, clearing had been done to enable repairs to the brickwork, but no uninterrupted view of the bridge was possible.

At Capel Lane Bridge, even though it wasn’t six, the light had gone and so the scout shot down Salterton Road and continued to the front, where he went to the end of Marine Drive before catching the 1826 train to Central.

He had clocked 45 miles when he returned to the utilicon.

The remainder of the line, from Capel Lane Bridge was covered the following day (22nd September), while it was fresh in the scout’s mind. He rode from Marsh Barton and started from Exmouth, but the photos are included here as the mileage is measured, from Waterloo.

Littleham

When the scout thanked the workman for moving the van, he was still unsure as to the purpose of the photograph. The scout explained that the place was Littleham Station and flung his arms around to point out the platforms, the yard, the crossing and the direction of the lines. The closure date, 1967, seemed, if not quite like yesterday to the scout, then certainly not very long ago, but was clearly beyond the young man’s comprehension. “You have a nice day,” he bade the scout as he rode away.

It occurred to the scout that he was again in a minority, this time for using a camera, now that so many use Smart walkie-talkies instead, with their very high quality lenses. Only the other day, the scout had found that the camera shop in Exeter where the railway’s Cybershot was bought had closed.

A man using a camera – positioning himself and framing the shot – is very obvious, whereas someone photographing with his “phone” could just be looking at the screen or searching for a signal.

When the railway was built, the road at right on which the silver can is parked was Bradham Lane and this was left on the lip of the cutting when the railway was finished. The other lip was behind the trees at left.

Bradham Lane now comes up the hill from Withycombe Raleigh and joins Salterton Road at the traffic lights. The short length of the former lane at right is now an access road.

The scout was never going to manage a refresher of both the Sidmouth and Budleigh branches in a day, even a long summer’s day; covering Tipton to Exmouth in a day proved too much as well.

In the area of Exmouth Viaduct, the experience was part refresher, part discovery, for the scout found much that he had never noticed before.

Exmouth Viaduct was the greatest engineering work on the line and its scale was testament to the intention the South Western must have had for the route; perhaps that it would cause the development of an East Devon “Metroland.”

As the scout roamed the area, he wondered what obstructions the contractor was faced with when he began construction of the line. An attempt to answer this is made below the continuing exploration of the route to the junction.

Understanding of this subject has been greatly advanced by reference to National Library of Scotland’s “Side by Side” resource and the wonderful 1930 aerial photos provided by “Britain from Above.”

Housing has taken the open space at top left and along the diverted Marpool Hill, but apart from the road expansion, the view would be much the same today. +

Withycombe Raleigh, at top right, is quite distinct from Exmouth; the scout often rides through it on the way down from Woodbury Common and reports that it retains the characteristics of a village, even though all the land around it, with the exception of Phear Park, is now under housing or trade premises. +

According to late 19th century O.S. maps, most of the area between the Exmouth Branch and Exeter Road was “The Marsh.” Since much of the low-lying area of the town is built on a sand spit, mirroring less obviously the Warren, it’s possible that before the railway embankment acted as a defence, it was salt marsh. The land was still being drained when the new embankment was sprung from the Exmouth Branch.

Beyond Exeter Road, housing development was underway. It is obvious that Park Road had been made because it went under a girder span, rather than being threaded through an existing arch. A terrace of houses had been built on the south side of Park Road but did it obstruct the railway? Ignoring the modern infill, the gap in the terrace is the width of eight houses and the end of the row to the east, whose back wing would once have been immediately adjacent to the viaduct, shows that at least one house was demolished.

It does not look as if any demolition was necessary in Withycombe Road.

Exmouth

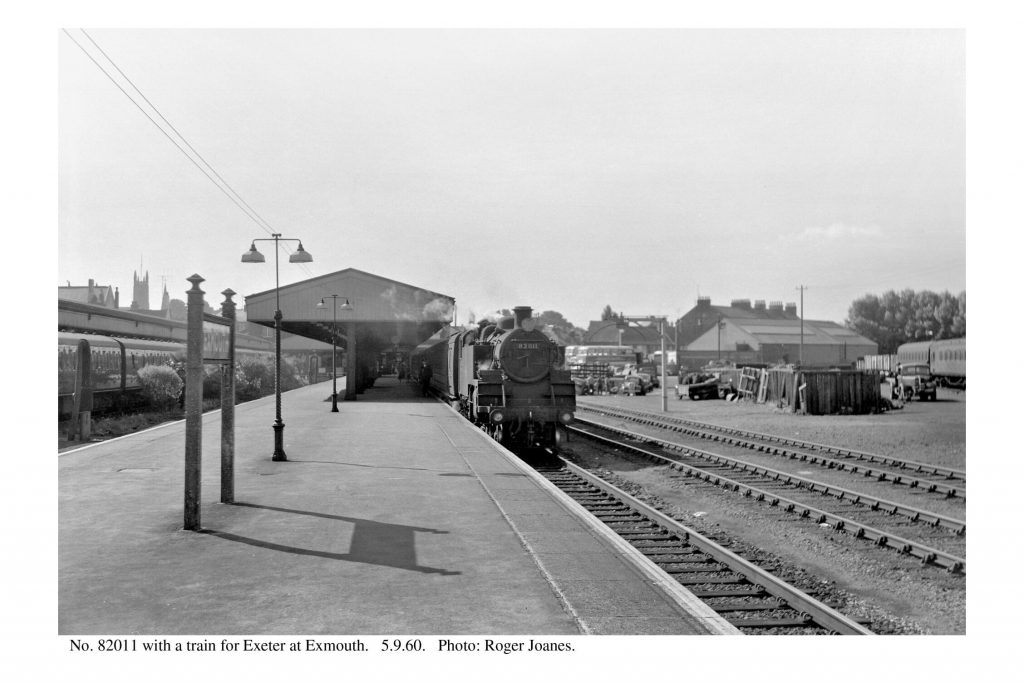

With the opening of the “Salterton” line in 1903, Exmouth became the terminus of two single line branches. In 1924, the station was rebuilt by the Southern Railway, with four platforms, a wide concourse and grand entrance building, which stood behind a frontage on Station Parade.

The scout, as a cub, vaguely remembers going through the disused booking hall with his father; in latter years tickets were sold from a hut at the side. Between trains, he and his dad once walked out to the derelict signal box and stood on the “bridge” where signalmen had held out or caught the tokens.

In 1976, a mean little building was put up part way along platform two and the rest of the station was demolished to make way for a long-planned relief road, which opened in 1981.

The replacement station can be seen next to Marks & Sparks‘s supermarket at left. +

A train can just be seen waiting to depart from the old platform. +

When taking the previous photographs, the scout had been on the pavement in front of the redbrick buildings at left.

Buses used to enter the station where the grass is now; the cobbled area edged the alignment. +

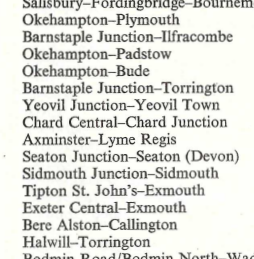

Every branch line terminus in Devon and Cornwall has either been closed or reduced. Ilfracombe, Bude, Callington, Padstow, Helston, Fowey, Turnchapel, Yealmpton, Kingsbridge, Kingswear, Princetown, Ashburton, Moretonhampstead, Sidmouth and Seaton were lost from the network years ago, along with many through stations. The ones that remain are either not the original termini (Barnstaple Junction, Gunnislake, Paignton) or they have been hemmed in and cut back, such as to be only pale, minimalized versions of their complete form (Newquay, St. Ives, Falmouth, Looe, Exmouth).

Despite being listed in the “Beeching Report,” the Exmouth Branch’s proposed closure was never acted upon and today closure would be unthinkable. The terminus is certainly not the least of the examples above, but it is hardly the worst. The line was shortened and the station was shrunk to a bare minimum to allow the expansion of the town’s road system, as part of the “stampede” policy, pursued now for a good hundred years, of providing for self-centred transport users who want to drive wherever they want, whenever they want. as far as they want and as often as they want, without any questioning of their purpose or of the overall or long term consequences.

In more recent years, a so-called “hierarchy of modes” is supposed to have prioritized public transport and “active travel” above the private motor car, but it is a pretence; the like-for-like replacement of vehicles in the drive to electrify the road system is proof that nothing has changed.

The transport revolution, which should have been the universal electrification of the railways and the expansion of tramways, has fallen into a mockery, with manufacturers spewing out filthy battery-electric vehicles to perpetuate the existing establishment at all costs.

Every pact with the devil plays out like this; there is no escape from the deal which looks so good but becomes an eternal curse. There seems to be no reversing, or even reining in, Lucifer’s promised “Autopia.”

The former imposing terminus is now a remnant of a station, likely soon to be unstaffed; the bus station has vanished; cyclists are forced onto the pavements and are poorly provided for on the trains; pedestrians are a kind of lower species; and the motorist continues to be sped on his way, mindless of any other considerations. This is the Exmouth seen in the photographs.

To finish, the scout wandered along Halsdon Road, whose terrace of houses he remembered seeing from the train when the single line ended at the adjacent platform four.