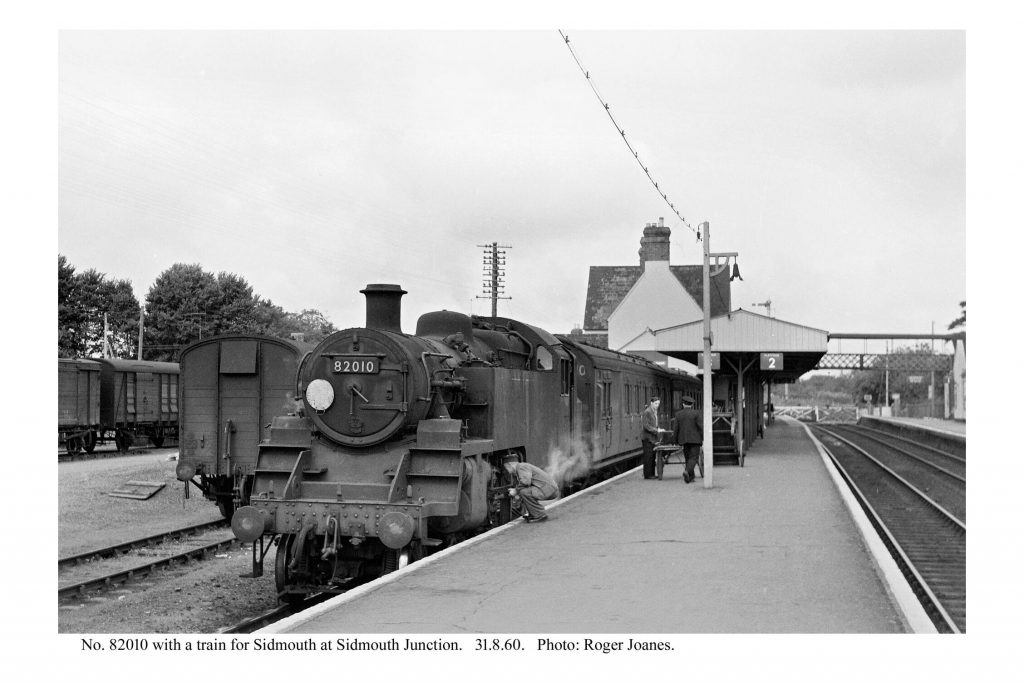

At the second attempt, the scout got to Sidmouth Junction, today’s Feniton.

His ride planned for 19th August had had to be abandoned because the 1025 to Waterloo was cancelled. On the later occasion, the same train arrived at Pinhoe on time but lost eight minutes waiting for a Down train to clear the single line. It was seven late away from Feniton but had made up six minutes on arrival at Waterloo.

The scout had thought that the station was unstaffed but found that the booking office opens for two and a half hours on weekday mornings.

When it was manned for a full turn, the scout remembered chatting to the member of staff and noted most passengers exchanging pleasantries with him as a familiar face. If all booking offices are threatened with closure, as is rumoured, then many small stations will become lonely places.

The barriers at the adjacent crossing were once controlled from the office, but this is now done remotely at Basingstoke.

Before wandering down the branch, the scout went over the crossing and spotted the sign pointing to the village; foolishly, he’d always thought the village surrounded the station.

He rode the three parts of a mile and was soon looking over the churchyard wall at St. Andrew’s. A voice behind him let him know that the church was open and that he was welcome to photograph within. The churchwarden, gardening with his two granddaughters, told the scout that the “transi” tomb was a remarkable survivor, being one of only 37 in the country.

As the detour to the village had already set him back, the scout decided not to look at the cadaverous sculpture on this occasion and rode sheepishly past the churchwarden’s garden.

Riding into the village, the scout had been struck by the very wide and deeply cut road. Leaving by way of Green Lane, he passed an even deeper cutting through the Otter sandstone.

The scribe normally respects copyright but, as these pages are seen by only a few, he has chosen to make an exception with the one below because it speaks volumes about the times.

In August, 1963, the 1.45 p.m. Exmouth to Waterloo is moving off after being brought to a stand at the junction home signal, which has been cleared for the main line.

The railway realm is in splendid order here. The track has recently been re-laid with bullhead rail on concrete sleepers; the cesses are immaculately kept, the linesides have been mowed – burnt at left. The fencing, much of it still there today, is concrete posts with high tensile wire and droppers. The engine drawing the five coaches (to which more will be attached at Seaton Junction) is only a little more than ten years old. Who could have foretold that within four years all this would be gone?

Another of the late Peter Gray’s photographs, taken from the opposite parapet, shows a 12-coach train from Waterloo leaving the junction with portions for Sidmouth and Exmouth.

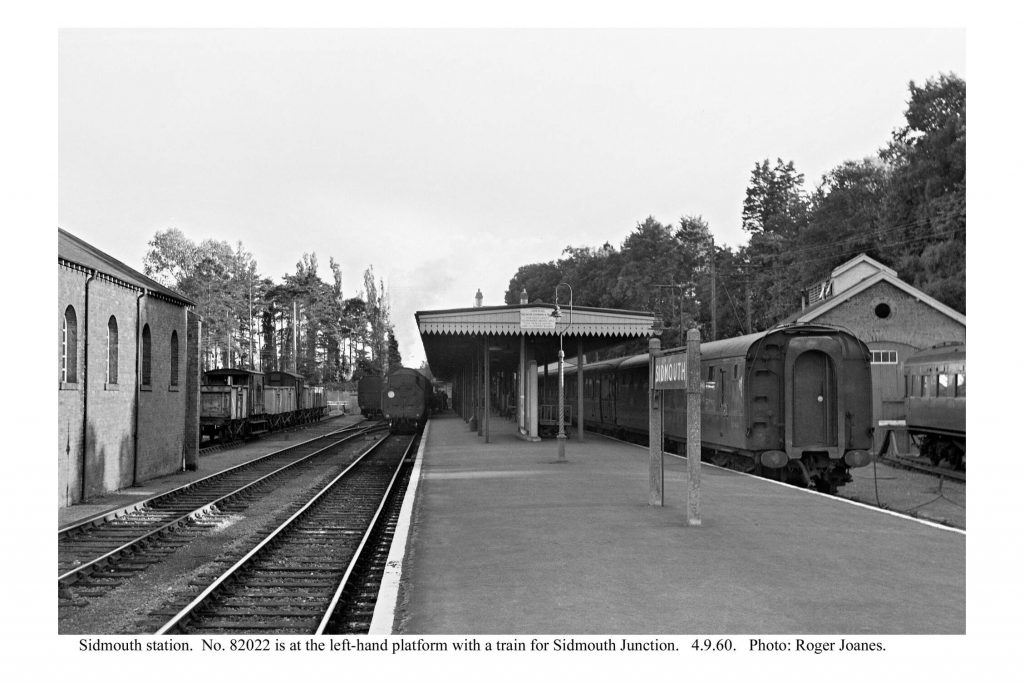

Some 175,000 passengers passed through Sidmouth Station annually during the 1960s; the line as a whole carried around 300,000. Yet this was not enough to keep it open. There has been much crowing in 2022 about the tremendous success of the reinstated service from Exeter to Okehampton, which has far exceeded expectations. But it is unlikely in its first year to match the figures above.

In 1967, the infrastructure – earthworks, bridges, stations, etc. – the rolling stock, the men and the huge untapped potential of the Sidmouth Branch was discarded by the stroke of a pen, enacting political connivance.

A lady was picking blackberries in what was once mid air. The scout cheekily asked her if she remembered the railway. She had moved to the village in 1976 when nothing remained of the line. She had, though, been a user of the Exe Valley. Her family had farmed near Cruwys Morchard. She had been a regular passenger from Bickleigh (she meant Cadeleigh) and the farm used to send goods traffic as well. For once the scout did not have to explain the many functions of a country station for the lady was very well aware of how much was done.

Even light traffic on the concrete surface creates a din which can be heard for miles.

The road severs the course of the railway where the second lorry is seen.

It was only a mile from here that, in 1996, “Swampy” (Daniel Hooper) was extracted from his tunnel, dug as a protest against the construction of this road, in particular the felling of ancient oaks that stood in its path.

The footpath joins the former A30 immediately beyond the bridge and continues to the railway’s overbridges. Close together are three roads: the original turnpike; the wider diversion; and the wretched dual carriageway.

Gosford Gates

The scout forsook the shorter footpath and rode via Gosford and Taleford to the next level crossing.

Cadhay Gates

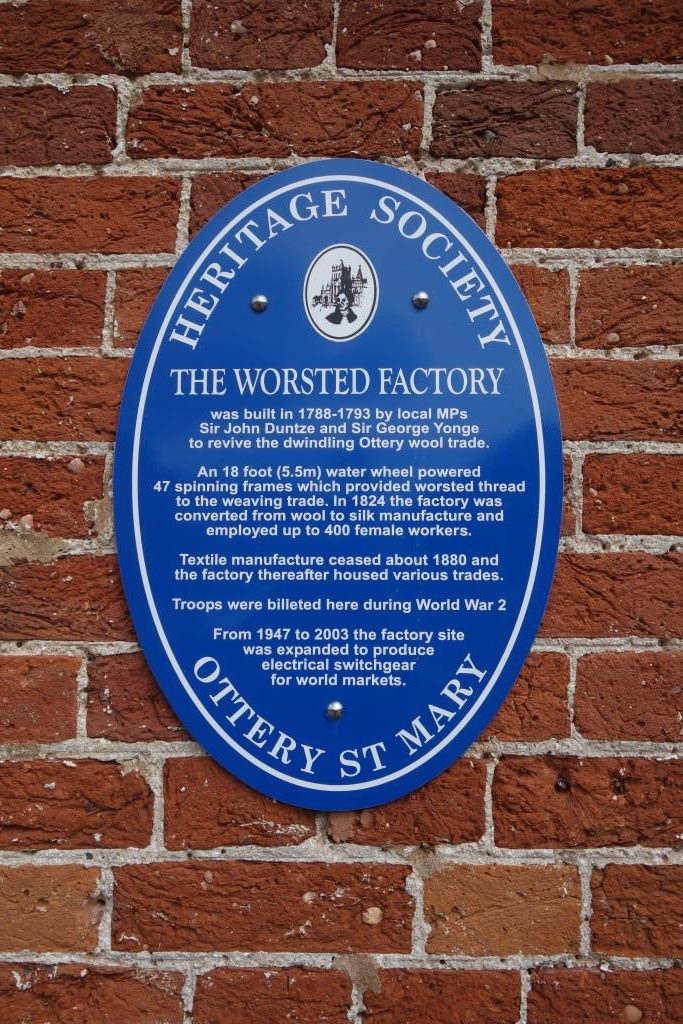

The scout had ridden through Ottery St. Mary in August, 2021 (Ride No. 56). He had photographed Otter Mill, which was in the process of being converted into flats. On his way to the station, seeing the work was finished, he turned into the new Tumbling Weir Way.

Another place, here productive for over 200 years, has been turned into a dreary dormitory for occupants who are unlikely to have any understanding of the activity that once made the walls hum.

The scout had read the plaque and was admiring the warm hue of the bricks, in which pebbles were entrained, when a fellow tapped the keypad by the door and let himself in. The scout nearly commented on the bricks but, perhaps unfairly, he judged the fellow to be a philistine.

The photographs the scout took of the station on his previous visit are repeated here. with the same text.

Ottery St. Mary

The station building and S.M’s. house at Ottery St. Mary still stand but have been rather clumsily extended.

A large trading estate has sprung up on and around the station since its closure. As everywhere else this has happened, it was simply inconceivable that any future functions could have been served by rail transport. This becomes an especially ridiculous failing when one of the traders is an Irish rail contractor, whose vans are seen racing around all over the country.

Just around the corner are the tatty units where the delectable Chunk pies and pasties are made.

The path along the valley doesn’t follow the formation from the former level crossing, but shortly meanders towards an embankment.

A line to Sidmouth would have had to cross the Otter. Had it been a line to Budleigh Salterton, however, what became two crossings could have been avoided.

The scout followed the path to the road leading towards Tipton St. Johns and pulled up at the former level crossing.

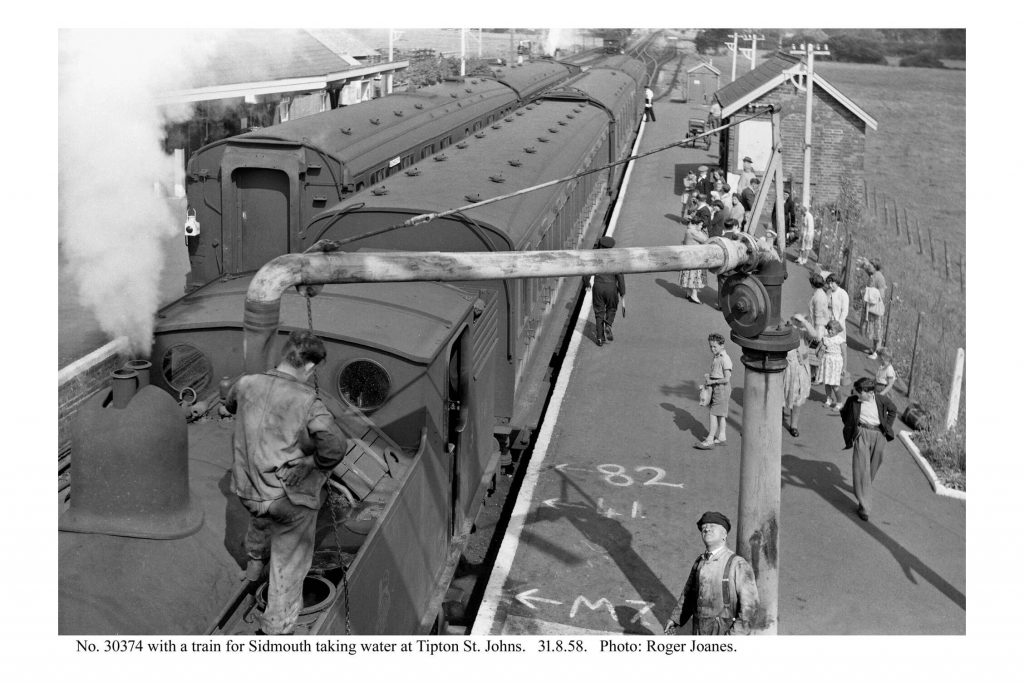

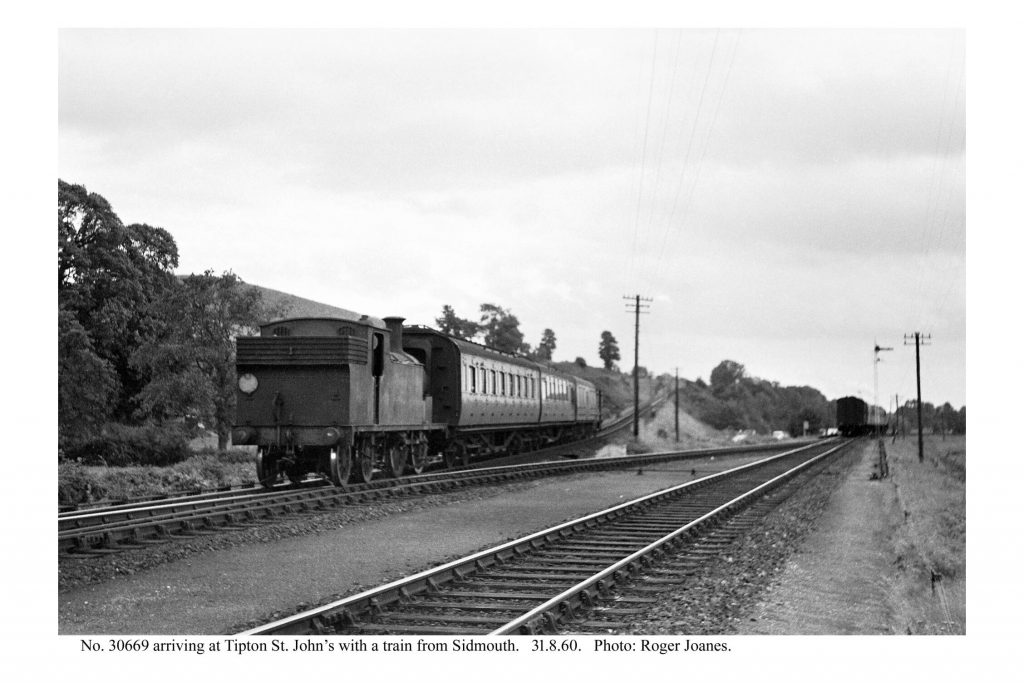

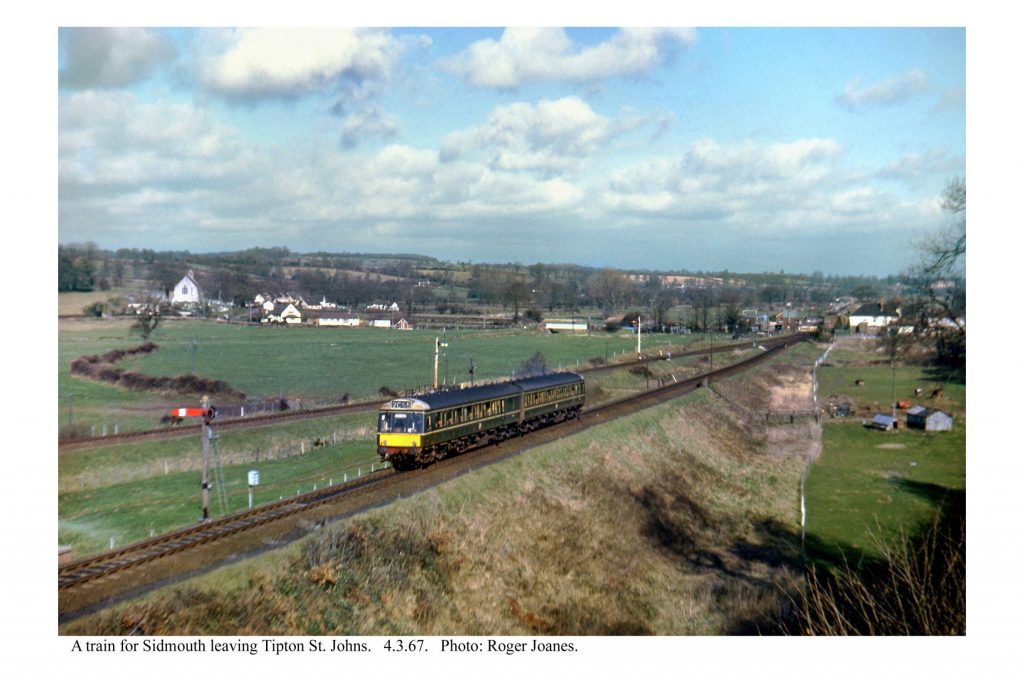

Tipton St. Johns

The locomotive, Adams “radial” No. 30583, built in 1885, was one of the three kept to work the Lyme Regis Branch and shedded at Exmouth Junction. The loco survives on the BlueBell Railway.

The scout searched among the houses built on the line at Tipton for obvious boundaries, but none could be seen.

At 1:45, it was a severe climb from the junction to the summit at Bowd. The descent to Sidmouth was not so severe but the scout was very conscious, as he sped down the hill, how much height was lost before he reached the station.

The mileage mark on Knapp’s Lane Bridge, above, should read “SID.” It carries a private track which is also a public footpath.

The climb to Bowd fascinates the scout because in places the railway’s earthworks are confused with the natural lie of the land. The landscape would have been much clearer from the train window.

A lady was pushing her bike up the 1:45. The scout passed her and then she passed him while he was looking for the culvert. When he caught up with her again, near the summit, the scout asked if she had considered trying an electric bicycle. She was capable of climbing the gradient, she told the scout, not quite indignantly, but liked to enjoy the surroundings on foot; and, no, she didn’t want an electric bike. A pleasant conversation ensued. She was returning to Sidmouth after riding to Willand with a club, a distance of around 40 miles. She said goodbye at the summit and the scout went to photograph the infilled bridge.

A great many wallowers in nostalgia would love to stand at the parapet on the right and hear an Ivaat tank barking on the incline. The scout would delight in the spectacle of the engine’s exhaust blasts being dispersed by the bridge, but is painfully aware that clinging to steam for far too long left the railway hopelessly outmoded when road motor transport came along to challenge the iron road’s supremacy.

Staff at Christow would prefer to look over that parapet wall and see a thin contact wire delivering clean electricity directly to the point of use. Staff would love to observe an E.M.U. breasting the summit from Sidmouth at full speed and then regeneratively braking, putting power back into the line while descending to the junction.

Gerard Duddridge, in his scholarly “South West Rail Strategy,” states that a 30-minute, or less, journey was possible between Sidmouth and Central, calling only at Ottery; and this with diesel traction.

Most motorists passing over the bridge at Bowd will probably not know that a railway once lay beneath, and certainly will have no grasp of the potential that was thrown away in 1967. Had that potential been realized by the 1950s, there would surely have been no mass closures in the 1960s.

The scout then rode a little way down the hill towards Sidford to see what had been done after the railway’s closure to speed motor traffic on its way.

The old road is still there, blocked at both ends and one abutment of the bridge gives away the alignment.

The course of the railway is opposite this sign, whose legs bear stickers.

Arising from crashes being made worse by vehicles colliding with road signs, the scout took it that the legs of this one are designed to break or crumple.

A person could also be standing beside the road who would not be “crash friendly.” The aim should not be to make everything beside the road less of a danger to the motorist, but to stop motorists driving their vehicles in a way that often makes them career off the road.

It was by now long past the scout’s lunchtime so he was anxious to career down the hill to find the Co-op. In next to no time, he came to a stop at the terminus.

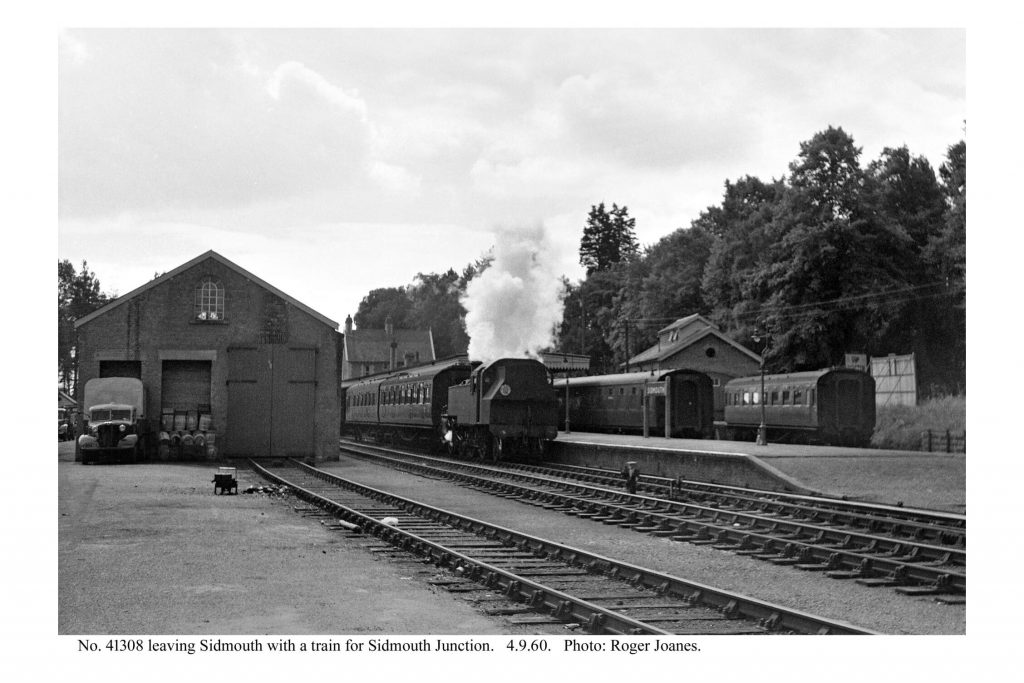

Sidmouth

Copyright: Tim Stephens.

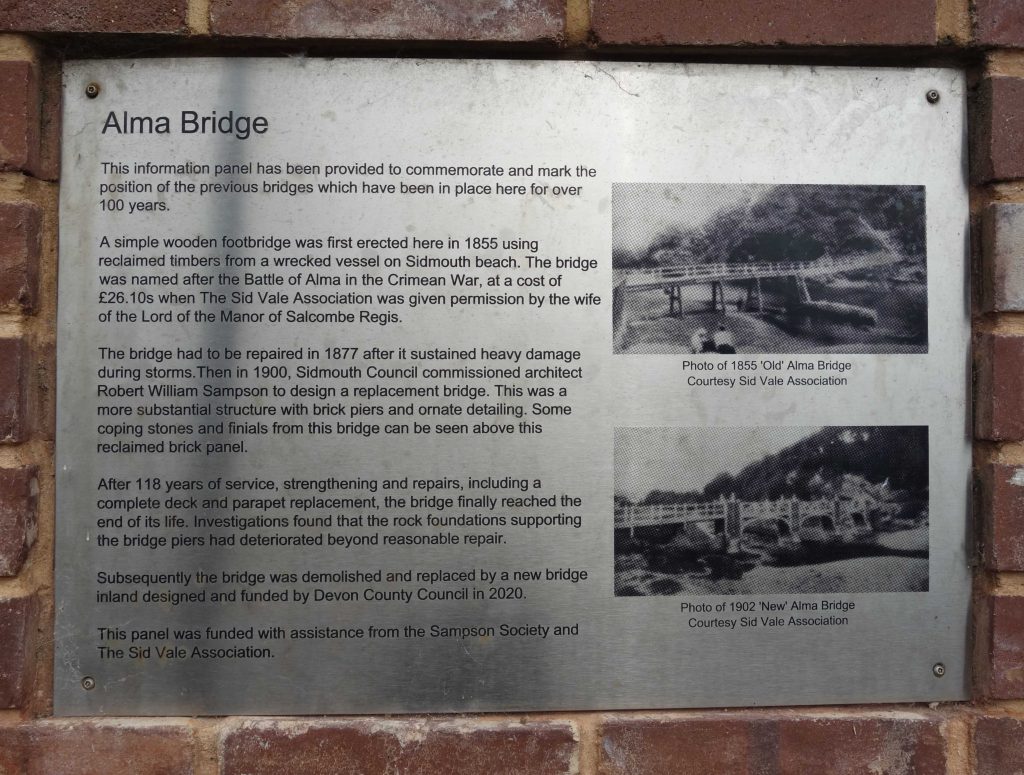

With lunch in his saddlebag, the scout wandered along the front to the river and found the old footbridge gone; he thought it had been closed on his last visit. A new bridge was opened upstream in 2020.

The Sid doesn’t make much of an entry into the sea; its flow after the long dry spell was scarcely enough to get across the shingle.

It was gone three when the scout seated himself on a bench and gazed along the stunning cliffs while scoffing lunch.

Peak Hill, to the west of Sidmouth, is not a climb for the faint-hearted.

From the top of the hill, the scout enjoyed an exhilarating descent to Otterton. He had planned to continue along the Budleigh Branch but the sun had knocked off for the day and it was thought better to devote another ride to this line.

Thus, he took the shortest route to Exmouth and caught the train to Newcourt. When he got back to the utilicon, he had clocked 38 miles.

While bombing along Salterton Road, the scout spotted these pictures at the back of a bus shelter. Oh for cycling to show this diversity in man and machine, and to be this happy.