The scout’s “Lunchtime 30” rides from Exeter often start out with no intention of looking at anything in particular and are meant merely to savour the sense of freedom that the bicycle bestows. But then something has him going to his saddlebag for the railway’s Cybershot.

Although the scout frequently passes Stoke Canon Crossing, and usually waits to see a train rush through, he has never photographed the old signal box. Seeing that the boarding on the window had been renewed, suddenly he thought that he would take a few frames for the library. The forlorn leftover was certainly a worthy subject, being the last remaining B. & E.R. box, built by Saxby & Farmer around 1874.

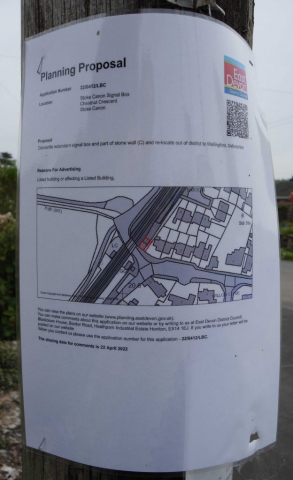

As the scout wandered around, he came upon a planning notice pinned to a post advising that an application had been received to take down the Grade II-listed building and remove it to Wallingford, on the former G.W. branch from Cholsey and Moulsford. Not the original Wallingford, sadly, for that is now covered in housing.

Three lads with a dog came from the footpath which connects with the Exe Valley line. As they passed, one was heard to remark: “There used to be a station here. We could have been in Exeter in a few minutes. And there was one at Brampford.”

“Here,” although the lad didn’t know it, was quite correct, for the original station was either side of the crossing, with the Up platform being opposite the box. This late 19th century survey shows the station but, strangely, not the crossing. The station was moved to the other side of the junction when the Exe Valley opened. The alignment of the lane before the railway was built is obvious.

Fortunately, Stoke Canon was unsuitable for conversion to an A.H.B. crossing. Several reasons can easily be guessed by looking at the approaches.

December, 2022: The wet spot had been dealt with in typical N.R. fashion.

A pleasant spot to lunch is convenient to Gillett’s store in Silverton, which does hot pasties and drinks.

Silverton Station lay over a mile and three quarters from here, the centre of the village; it was just under two miles to Thorverton. Six roads converge here; two were once the ancient high road from Exeter to Tiverton. The later turnpike avoided the village and followed the Exe Valley all the way.

After lunch, the scout descended past the church to Hayne Farm and set off across ground made firm by lack of rain to the infrequently used Silverton Crossing.

The line speed is 100 m.p.h. The sighting is good but whistle boards are provided. On average, 95 trains pass here each day.

The signs on the posts indicate that these are automatic signals, worked by the passage of trains. The three-aspect “UM187,” showing green, indicates that the line is clear at least for the next two signal sections, plus a 300-yard safety overlap.

At Ellerhayes, a lady stopped her car and asked the scout if he’d seen a running man. When he said that he had seen no one, she advised that the man had overturned a van and that the scout should call 999 if he saw the runner. A helicopter had been flying around and the scout had thought it was Western Power checking the overhead lines. It’s a good thing he hadn’t misbehaved near the railway line; not that he ever does, of course.

The next bridge after Silverton is Clysthayes, wrongly labelled by the track authority.

The scout had heard several trains pass on the Down and as he returned to Silverton he just missed the short H.S.T. he would have preferred to see.

The police helicopter continued to sweep and circle, making the scout feel as if he were being watched. A police car raced up and stoppped. The W.P.C. in the passenger seat could have been a 15-year old doing “work experience” with her dad. The driver spoke across her and asked if the scout had seen two running lads. Mimicking a telephone receiver with his hand, the motor constable barked “999, if you do” and sped off. A police van gave chase moments later.

It was pleasant in the sun but the scout would rather not have spent quite so much of the afternoon waiting for a train to occupy the line in the shot below; there is a 40-minute gap in the timetable. The “chopping” from above and the drone of the M5, which joins the Culm Valley just north of here, made it far from peaceful.

Driver and Fireman seem intent on the camera for some reason. +

Like the original Stoke Canon, Silverton’s platforms were offset, a diagonal barrow crossing beneath the bridge connecting them. A poor woman died here in 1878. This extract wrongly pictures Clysthayes Bridge.

Along with Wellington, Burlescombe, Sampford Peverell, Cullompton and Hele & Bradninch, Silverton closed to passengers in 1964, bringing an end to the Taunton-Exeter stopping service. Silverton closed to goods in 1965, but a private siding remained open until 1967.

This made a connection with G.W. metals in the goods yard, opposite the Up platform. It is remarkable for having remained almost completely intact. The reason is obvious: the whole of the line is set in concrete so that, certainly in latter years, shunting could be done by a tractor equipped with a buffer beam and coupling, like the one that survived at the Hele mill until the early 1980s. Were it not for this, the track would have been torn up shortly after closure, leaving only a bit of formation as evidence that it was ever there.

The scout has often thought of asking the landowner if he would allow the Christow motor trolley to traverse the line. This would entail an awful lot of work, as the flangeways would need to be cleared with a pick, but it would undoubtedly be fun.

A little further towards Bridge Paper Mill, the line’s destination, is found the weighbridge.

This was taken in 2015, while the scout was riding to Taunton.

It is not known whether the driver of the Network Rail van was about any useful task.

The River Culm, the reason for the mill having been here, lies just beyond the fir trees.

Just up the hill from the bridge is the turning to the mill and Bridge Lane. Last time the scout was here, the camera’s battery was flat. With no need to remove the foliage this time, the scout photographed the sign, which remains over twenty years after the place ceased to be the home of “Innovation & Conservation in Papermaking.”

It is only a short way to the gate, where the scout expected to see what he had seen on all previous occasions: a car and a burly security fellow sitting at a desk by an office window.

But today there was no car and no face. “Had burly fellow gone to get some grub? Would he return at any moment? Had the watch been withdrawn?” were thoughts that crossed the scout’s mind as he went through the gap by the gatepost. The mill cat had refused to leave and someone was still coming, as food and water bowls had been left in the porch.

So far as papermaking goes, there is nothing left on the site to see, all trace of the functional buildings having been removed as part of a £4.5-million remediation project in 2017. The last two buildings had only recently been demolished; the two former employees that the scout had had a long chat with while on his Taunton ride the previou year were posting the statutory notices.

The staff at Christow, never being concerned with rail transport alone, would very much like to read more about Culm Valley papermaking. For now, all that is known comes from this article from D.S. Smith, the successor to Reed & Smith, the owner of the private siding when it was operational. This Ordnance Survey extract shows the station, the siding and the mill complex as it was before the First World War. And Britain from Above has a wonderful 1933 aerial view, reproduced in low resolution below.

The place seems to have been undiscovered by those with a wont to cause damage – not a single window has been broken – and the scribe is almost fearful of publishing the images below; he does so with the belief that these pages are read only by a few.

December, 2022: On another “Lunchtime 30” while Earth momentarily stopped at “top dead centre,” the scout looked in at the mill again. Remarkably, for a place that has been completely abandoned, there was no sign whatsoever of damage. Once, destructive youths or “architectural salvors” would have descended on a place like this almost immediately.

Narrow gauge lines are laid on the dump in the foreground.

Most of the buildings seen in the scout’s shots can be picked out.

The big chimney’s smoke can at first be taken as tree foliage.

The Culm is on the right, with the leat at left, both passing beneath the buildings.

Someone who once worked for the old Water Board told the scout that a net stretched across the Culm downstream of the mill would quickly become completely clogged. Pollution came from the tannery at Cullompton as well as the other mills. The state of the Culm was the reason why the intake from the Exe for Exeter’s Pynes treatment works was above the confluence.

D.H. Smith’s article states that up to 45,000 tons of paper were produced here before the mill closed in 1999. There must be countless places where the railway abandoned sources of traffic. From energetically seeking new business, the railway went in a decade to being happy that no raw materials or finished products to and from Silverton would ever again pass by rail. However, the railway did continue to trip coal to Wiggins Teape’s Devon Valley Mill at Hele until the early 1980s. Run by Purico, this is still open, producing the likes of teabag paper. Its rail lines can also be seen embedded in concrete.

The mill’s importance warranted its own direction sign. +

September, 2024: The scout stopped at the gate while following the main line and found that several temporary camera standards had been placed around the site.

The trunk transport corridor of the Culm Valley was left behind as the scout climbed to Ashclyst Forest, which was deserted a day before the Easter weekend. The well-kept houses belonging to the National Trust, part of the huge Killerton Estate, stand out in their traditional renders.

On his way back to town, via Broad Clyst, the scout thought about his foray into the old mill. He wished he had seen it when it was in operation but then wondered how differently he would have felt about seeing the cleansed space where it had been. It was not his industry but it was a place where men and women worked and won their livelihoods; many would have known nothing else, like their kin before them. In a country where more and more people are employed in meaningless drudgery, doing each other’s washing or scratching each other’s backs, while serious production goes on overseas, the loss of somewhere like Silverton Mill, rooted in place, tied to its water, over perhaps half a millennia, should bring out sadness and unease in any real Englishman (31 miles).